Disaster Evacuation from Japan's 2011 Tsunami Disaster and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greetingsfrom Koriyama City

‘Nunobiki Plateau Wind Farm’: boasting 33 wind turbines with the height of roughly 100 meters, one of the largest scale wind farms in Japan Greetings from Koriyama City -Toward a future-oriented and mutually-beneficial relationship between the cities of Essen and Koriyama- Business Creation Division City of Koriyama, JAPAN City of Koriyama, Fukushima Prefecture JAPAN 1 Geographical Features of Koriyama City -Two Cities of Essen and Koriyama- 2nd most populous in Fukushima Prefecture and 3rd most populous in Tohoku Region ‘Economic Capital City in Fukushima Prefecture’, boasting its Essen City biggest retail sales and largest number of retail businesses in the prefecture Largest number of agricultural households in Fukushima State of North Rhine- Prefecture, boasting biggest rice production in the prefecture Westphalia 51 Degrees 37 Degrees Koriyama City Fukushima Prefecture Koriyama City Central urban area of Koriyama City (the west exit of Koriyama Station) City of Koriyama, Fukushima Prefecture JAPAN 2 History of the Development of Koriyama City -Transition from a city of power generation to city of renewable energy and medical devices- 5.Great East Japan 6.Restoration Earthquake and Nuclear Accident from the disasters, at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear promoting renewable Power Station in 2011 energy and medical device development Oyasuba Burial Mound, built in the Fukushima Renewable Energy early Kofun Period (250 AD-538 AD) Institute, AIST (FREA) opened in April 2014 Building with its first floor collapsed due to the fierce earthquake 4.People gathered, schools and banks established, Fukushima Medical Device Development Numagami Hydroelectric Power Station, laid Support Center (FMDDSC) the foundation of Koriyama’s development railroaded to become the center of Fukushima Prefecture opened in November 2016 3.New industry revolution, cotton and chemical industries flourished by hydro electric power generation, Hodogaya Chemical Co., LTD. -

Mainichi Newspapers' Database

http://mainichi.jp/contents/edu/maisaku/ Maisaku's quick search Mainichi public opinion search Whole new database on opinion polls You can search for the results of opinion polls that the Mainichi Shimbun has conducted since the end of World War II by entering keywords and dates. You can view the pages that carry the Fixed-rate database service opinion polls you search for. The database carries records by for libraries and gender and age that are not carried in the paper as well as graphs education institutions showing the approval ratings of Cabinets and political parties in the post-war period. You can effectively use materials in the database as basic data for political science and statistics. We regularly update the data. Mainichi Newspapers' database Period of storage: October 1945 ~ http://mainichi.jp/contents/edu/maisaku/ Contents: 1.The results of about 400 opinion polls covering eligible voters across the country (Questions, answers and survey methods. Records by gender and age since 1966 are carried.) 2.Graphs showing the approval ratings of Cabinets and political parties,and so on. Database that allows you to search information Fixed monthly fees from the to eras Fee structure Free trial Meiji Heisei Number of accesses Monthly fees Annual fees We offer a one-month free trial. You can use Maisaku for free on a one month trial basis. 1 24,000 yen (excluding tax) 288,000 yen (excluding tax) 2 44,000 yen (excluding tax) 528,000 yen (excluding tax) Guidance ID yen excluding tax yen excluding tax 3 60,000 ( ) 720,000 ( ) We will issue IDs for our users. -

Inside and Outside Powerbrokers

Inside and Outside Powerbrokers By Jochen Legewie Published by CNC Japan K.K. First edition June 2007 All rights reserved Printed in Japan Contents Japanese media: Superlatives and criticism........................... 1 Media in figures .............................................................. 1 Criticism ........................................................................ 3 The press club system ........................................................ 4 The inside media: Significance of national dailies and NHK...... 7 Relationship between inside media and news sources .......... 8 Group self-censorship within the inside media .................. 10 Specialization and sectionalism within the inside media...... 12 Business factors stabilizing the inside media system.......... 13 The outside media: Complementarities and role as watchdog 14 Recent trends and issues .................................................. 19 Political influence on media ............................................ 19 Media ownership and news diversity................................ 21 The internationalization of media .................................... 25 The rise of internet and new media ................................. 26 The future of media in Japan ............................................. 28 About the author About CNC Japanese media: Superlatives and criticism Media in figures Figures show that Japan is one of the most media-saturated societies in the world (FPCJ 2004, World Association of Newspapers 2005, NSK 2006): In 2005 the number of daily newspapers printed exceeded 70 million, the equivalent of 644 newspapers per 1000 adults. This diffusion rate easily dwarfs any other G-7 country, including Germany (313), the United Kingdom (352) and the U.S. (233). 45 out of the 120 different newspapers available carry a morning and evening edition. The five largest newspapers each sell more than four million copies daily, more than any of their largest Western counterparts such as Bild in Germany (3.9 mil.), The Sun in the U.K. (2.4 mil.) or USA Today in the U.S. -

The Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Crisis Management

e Fukushima Nuclearand Crisis Accident Management e Fukushima The Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Crisis Management — Lessons for Japan-U.S. Alliance Cooperation — — Lessons for Japan-U.S. Alliance Cooperation — — Lessons for Japan-U.S. September, 2012 e Sasakawa Peace Foundation Foreword This report is the culmination of a research project titled ”Assessment: Japan-US Response to the Fukushima Crisis,” which the Sasakawa Peace Foundation launched in July 2011. The accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant that resulted from the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011, involved the dispersion and spread of radioactive materials, and thus from both the political and economic perspectives, the accident became not only an issue for Japan itself but also an issue requiring international crisis management. Because nuclear plants can become the target of nuclear terrorism, problems related to such facilities are directly connected to security issues. However, the policymaking of the Japanese government and Japan-US coordination in response to the Fukushima crisis was not implemented smoothly. This research project was premised upon the belief that it is extremely important for the future of the Japan-US relationship to draw lessons from the recent crisis and use that to deepen bilateral cooperation. The objective of this project was thus to review and analyze the lessons that can be drawn from US and Japanese responses to the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, and on the basis of these assessments, to contribute to enhancing the Japan-US alliance’s nuclear crisis management capabilities, including its ability to respond to nuclear terrorism. -

606 Atomic Bomb Suffering and Chernobyl Accident Lessons Learnt from International Medical Aid Programs

JAERI-Conf 2005-001 606 Atomic Bomb Suffering and Chernobyl Accident Lessons learnt from International Medical Aid Programs Shunichi YAMASHITA* Department of Molecular Medicine, Atomic Bomb Disease Institute, Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences 1-12-4 Sakamoto, Nagasaki 852-8523, Japan T8528523 SitTffK^ 1-12-4, E-mail: [email protected] mm 3 hj ^- * Current position; Scientist at the Department of Radiation Program, Sustainable Development and Healthy Environment, WHO/HQ in Geneva, [email protected] - 387 - JAERI-Conf 2005-001 Abstract The cooperative medical projects between Nagasaki University and countries of the former USSR have had being performed in mainly two regions: Chernobyl and Semipalatinsk since 1990 and 1995, respectively. The 21st Center of Excellence (COE) program of "International Consortium for Medical Care of Hibakusha and Radiation Life Science" recently established in Nagasaki University can now serve our knowledge and experience much more directly. Its activity can be further extended to the radiocontaminated areas around the world, and based on the lessons of the past, it can indeed contribute to the future planning of the Network of Excellence (NOE) for Radiation Education Program as well as Radiation Emergency Medical Preparedness and Assistance under the auspices of the WHO-REMPAN. Within the frame of International Consortium of Radiation Research, a molecular epidemiology of thyroid diseases are now conducted in our departments in addition to international medical assistance. The clue of radiation-associated thyroid carcinogenesis may give us a new concept on experimental and epidemiological approaches to low dose radiation effects on human health, including those of internal radiation exposure. -

Mainichi Shimbun Digital Archive

Mainichi Shimbun Digital Archive The oldest existing Japanese daily newspaper The Mainichi Shimbun (毎⽇新聞, Daily News) is the oldest existing Japanese daily newspaper with a history spanning over 140 years. It continues to be one of the most important daily newspapers in Japan today. Dramatic and fundamental changes were taking place in Japan during the Meiji era (1868-1912) when reforms were implemented in education, economics, the military, foreign relations, and politics. During these transformative years, two newspapers were established: the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun (東京日日新聞) in 1872, and the Osaka Nippo (大 阪日報) in 1876. The two papers merged in 1911 and were placed under the Mainichi Shimbun masthead in 1943. Key Stats About the Archive Archive: 1872-present The Maisaku database provides access to over 6 million articles from Mainichi Language: Japanese Shimbun since 1872 to present and the Mainichi Weekly Economist from 1989. Frequency: Daily Newspaper images from 1989 to 1999 are in flash format, which include features like page turning, scaling, bookmarking, etc., as in an electronic book. City: Chiyoda, Tokyo Format: full text and some full image The Maisaku database is divided into the following search modules: Producer: G-Search, Ltd. Quick Search: Full-text searching Mainichi Shimbun, 1872–present and Weekly Platform: G-Search, Ltd. Economist from 1989 Mainichi Shimbun Article Search: Advanced search Full-Image Mainichi Shimbun: Browse full-image, 1872-1999 Mainichi Shimbun E-Edition: Browse the full-image, flash version, 1989-1999 Weekly Economist article search Today’s News: News, updated twice daily. Read news from past week Breaking News: Updated every 10-20 minutes. -

Betrayed by Nuclear Power Transforming the Community and Collective Memory of Fukushima’S Evacuees

Leiden University, Faculty of Humanities Asian Studies 120EC: Japanese Studies MA Thesis Betrayed by Nuclear Power Transforming the Community and Collective Memory of Fukushima’s Evacuees Author: Nick Sint Nicolaas Student Number: 1059998 Supervisor: Dr. A.E. Ezawa Second Reader: Dr. M. Winkel Date: December 15, 2015 Word count: 14,043 Table of Contents I: Introduction…………………………………………………………………………….……… 3 Disaster Background ..….….….………………………………………………….……… 5 II: Theoretical Framework ...…………………………………………………………………….. 8 Communities …………………………………………………………………………….. 8 Community Attachment …………………………………………………………………. 9 Collective Memory …………………………………………………………………….. 10 Disasters ...……………………………………………………………….….….………. 12 III: Japan’s Nuclear History ...………………………………………………………………….. 16 Postwar Nuclear Allergy.……………………………………………………………..… 16 Localized Pro-Nuclear Strategies ……………………………………………………… 18 Post-Disaster Nuclear Discourse …...……………………………..….………………… 20 IV: Analysis ……………………………………………….…………………...………………. 23 Futaba ………………………….……………………………………………………….. 25 Mayor Idogawa: Representing the Collective ………………………………………….. 27 Decontamination Waste Storage: Taint vs Absolute Loss ...…………………………… 30 The Elderly: Futility ……………………………………………………………………. 33 Temporary and Core Communities ……………………………….……………………. 34 Nakai Family: In the Face of Absolute Loss ……………………..…………….……… 35 Suzuki Family: Salvaging Treasures and Moving On ……………………………….… 36 Widow Umeda: Holding On to What Remains …………….………………………….. 38 Saito Family: Forsaking a Legacy ……………………………………………………... 39 Farmer -

Evidence-Based Guidelines Needed on the Use of CT Scanning in Japan

Review Article Evidence-based Guidelines Needed on the Use of CT Scanning in Japan JMAJ 48(9): 451–457, 2005 Nader Ghotbi,*1,2 Mariko Morishita,*1,2 Akira Ohtsuru,*1 Shunichi Yamashita*2,3 Abstract The increasing use of medical radiation, especially in diagnostic computed tomography (CT) scanning, has raised many concerns over the possible adverse effects of procedures performed without a serious risk versus benefit consideration, particularly in children. The growth in the number of CT scanning installations and usage, some new and unprecedented applications, the relatively wide variation of radiation doses applied by different radiological facilities, and the worrisome estimations of increased cancer incidence in more susceptible organs of children all point to the need for a clear specification of evidence-based guidelines to help limit and control the amount of radiation doses the Japanese population is being exposed to through medical diagnostic imaging technologies. Recommendations have already been issued on how to reduce the exposure dose to the minimum required especially in pediatric CT but more work is needed to establish good practice principles by the medical community through determination of more reasonable indications to request CT scanning. Key words Computed tomography (CT) scanning, Evidence-based guidelines, Medical radiation, Pediatric CT, Radiation induced cancer in the average annual collective radiation doses Introduction (Fig. 1b). The risk of cancer induction by medical The average annual collective doses of ionizing radiation is not a recent issue but a long-standing radiation exposure to the UK population from one.2 Fortunately, the radiation doses of all all sources have been summarized in a recent common diagnostic radiological examinations review1 that depicts a good example of the latest have generally been decreasing, except for situation of radiation exposure in developed computed tomography (CT) and interventional countries. -

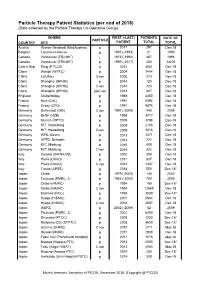

Particle Therapy Patient Statistics (Per End of 2018) (Data Collected by the Particle Therapy Co-Operative Group)

Particle Therapy Patient Statistics (per end of 2018) (Data collected by the Particle Therapy Co-Operative Group) WHERE FIRST (-LAST) PATIENTS DATE OF PARTICLE COUNTRY SITE PATIENT TOTAL TOTAL Austria Wiener Neustadt (MedAustron) p 2017 297 Dec-18 Belgium Louvain-la-Neuve p 1991 (-1993) 21 1993 Canada Vancouver (TRIUMF) p- 1979 (-1994) 367 1994 Canada Vancouver (TRIUMF) p 1995 (-2017) 204 Jul-05 Czech Rep. Prag (PTCCZ) p 2012 3551 Dec-18 China Wanjie (WPTC) p 2004 1444 Dec-18 China Lanzhou C-ion 2006 213 Dec-18 China Shanghai (SPHIC) p 2014 123 Dec-18 China Shanghai (SPHIC) C-ion 2014 723 Dec-18 China Shanghai (SPHIC) p&C-ion 2014 887 Dec-18 England Clatterbridge p 1989 3450 Dec-18 France Nice (CAL) p 1991 6394 Dec-18 France Orsay (CPO) p 1991 9476 Dec-18 Germany Darmstadt (GSI) C-ion 1997 (-2009) 440 2009 Germany Berlin (HZB) p 1998 3417 Dec-18 Germany Munich (RPTC) p 2009 3798 Dec-18 Germany HIT, Heidelberg p 2009 2186 Dec-18 Germany HIT, Heidelberg C-ion 2009 3016 Dec-18 Germany WPE, Essen p 2013 1471 Dec-18 Germany UPTD, Dresden p 2014 721 Dec-18 Germany MIT, Marburg p 2015 408 Dec-18 Germany MIT, Marburg C-ion 2015 322 Dec-18 Italy Catania (INFN-LNS) p 2002 350 Dec-18 Italy Pavia (CNAO) p 2011 837 Dec-18 Italy Pavia (CNAO) C ion 2012 1307 Dec-18 Italy Trento (APSS) p 2014 550 Dec-18* Japan Chiba p 1979 (-2002) 145 2002 Japan Tsukuba (PMRC, 1) p 1983 (-2000) 700 2000 Japan Chiba (HIMAC) p 1994 150 Dec-18* Japan Chiba (HIMAC) C ion 1994 12649 Dec-18 Japan Kashiwa (NCC) p 1998 3000 Dec-18* Japan Hyogo (HIBMC) p 2001 5984 Dec-18 Japan -

Fukushima Prefecture Training Camp Guidebook

Fukushima Prefecture Training Camp a i n i n g t a g e o f T r C a m p s i n F Guidebook d v a n U K U S k e A H I M A T a ! ! T a k e H I M A A d v a n F U K U S t a g e o f T r a i n i n g C a m p s i n Message from the Governor of Fukushima Prefecture Support Messages Ms. Yuko Arimori Olympic medalist Profile highlights ▪ Silver medalist, Barcelona 1992 Olympic Women’s Marathon ▪ Bronze medalist, Atlanta 1996 Olympic Women’s Marathon ▪ Honored in 2010 with IOC Women and Sport Awards for the first time as a Japanese Current positions: Specified NPO “Hearts of Gold” Founder and Representative Director; President & CEO, Special Olympics Nippon Foundation; Director, Japan Professional Football League; Health Ambassador appointed by Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare; Visiting Professor, Shujitsu University; Visiting On behalf of all citizens of Fukushima Prefecture, let me express my Professor, Nippon Sport Science University; Shakunage Ambassador for Fukushima Prefecture, among other positions CONTENTS heartfelt gratitude for the great support, cooperation and encouragement you have extended to us from around the world since our prefecture I’d like Athletes from around the world Message from the Governor was severely stricken by the Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, to give children in Fukushima dreams. of Fukushima Prefecture … 1 2011. Support Messages ………… 2 It is true that Fukushima Prefecture still faces some Introduction of problems remaining in the wake of the Great Fukushima Prefecture ……… 3 We, residents of Fukushima Prefecture, have been deeply impressed East Japan Earthquake in 2011. -

Mr. Michael Walsh

Slide Presentation Presented at the UNEP/OECD Meeting on Lead in Gasoline 12-13 December, 1996 (Paris) by Mr. Michael Walsh Consultant from Car Lead in Gasoline The Need For and Options For Its Elimination Why Was Lead Added To Gasoline? Low Cost Octane Enhancer Higher Octane Allowed Better Engines More Efficient Higher Power Output Lead In Gasoline Causes Serious Problems High Ambient Lead Levels Precludes The Use of Catalytic Converters To Reduce CO, HC and NOx High Vehicle Maintenance Costs Adverse Health Effects From Lead At low doses, toxic to brain, kidney, reproductive and cardiovascular systems Manifestations include impairments in intellectual function, kidney damage, infertility, miscarriage, and hypertension. At high exposures, lead is lethal to humans, inducing convulsions and irreversible hemorrhage in the brain. Long term exposures associated with increased risks of kidney cancer. Other Adverse Health Effects reduced sperm counts crosses the placenta and is accumulated by the fetus reduced birth weight reduced fetal skeletal growth Other Adverse Health Effects - Continued increased blood pressure in adults population-based studies in which lead exposure and blood pressure are measured prospective studies in which blood pressure is monitored in persons as their lead exposures increase (usually in occupational settings, eg traffic police) case control studies in which lead exposure is measured and compared in persons with and without diagnosed hypertension Children Are Especially Susceptible increased likelihood of exposure, -

Overview of the Fukushima Nuclear Plant Accident and Early Response

Overview of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant Accident and Early Response Shunichi Yamashita, MD., PhD. Center for Advanced Radiation Emergency Medicine, National Institutes for Quantum and Radiological Science and Technology, and Fukushima Medical University, Japan On behalf of the Japanese colleagues in the arena of radiation emergency medicine and dose evaluation, it is highly appreciated and a really turning point to have the WHO- REMPAN on-line web symposium in this special occasion of the ten years since the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake and the subsequent accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (NPP), but significant challenges still remain. All of the REMPAN members surely remember or recall, just 10 years ago in Nagasaki, three weeks before the unforeseen Fukushima NPP accident, the 13th WHO-REMPAN meeting was held and discussed deeply about the necessity of practical approach for radiation emergency medicine, including strengthening the internal communication within the network through the current WHO-REMPAN newsletters. This overview recalls what really happened just after the Fukushima NPP accident and presents the lessons learned from the initial chaos and confusion of the Fukushima accident. The declining creditability of the Japanese governmental and official bodies may worsen the difficult situation of radiation fear and anxiety. The Fukushima NPP accident has also severely shattered public faith in the academic societies and international regulatory bodies. Therefore, it is important to regain public trust and narrow the gaps in knowledge between the experts and the public on the stochastic effects of low-dose radiation exposure, where a large uncertainty exist, and on public health emergency and wide radio-contamination areas from the nuclear disaster, which poses a real problem.