Shoot the Moon – 1967

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geoscience and a Lunar Base

" t N_iSA Conference Pubhcatmn 3070 " i J Geoscience and a Lunar Base A Comprehensive Plan for Lunar Explora, tion unclas HI/VI 02907_4 at ,unar | !' / | .... ._-.;} / [ | -- --_,,,_-_ |,, |, • • |,_nrrr|l , .l -- - -- - ....... = F _: .......... s_ dd]T_- ! JL --_ - - _ '- "_r: °-__.......... / _r NASA Conference Publication 3070 Geoscience and a Lunar Base A Comprehensive Plan for Lunar Exploration Edited by G. Jeffrey Taylor Institute of Meteoritics University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico Paul D. Spudis U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Astrogeology Flagstaff, Arizona Proceedings of a workshop sponsored by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C., and held at the Lunar and Planetary Institute Houston, Texas August 25-26, 1988 IW_A National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Management Scientific and Technical Information Division 1990 PREFACE This report was produced at the request of Dr. Michael B. Duke, Director of the Solar System Exploration Division of the NASA Johnson Space Center. At a meeting of the Lunar and Planetary Sample Team (LAPST), Dr. Duke (at the time also Science Director of the Office of Exploration, NASA Headquarters) suggested that future lunar geoscience activities had not been planned systematically and that geoscience goals for the lunar base program were not articulated well. LAPST is a panel that advises NASA on lunar sample allocations and also serves as an advocate for lunar science within the planetary science community. LAPST took it upon itself to organize some formal geoscience planning for a lunar base by creating a document that outlines the types of missions and activities that are needed to understand the Moon and its geologic history. -

Mars Express Orbiter Radio Science

MaRS: Mars Express Orbiter Radio Science M. Pätzold1, F.M. Neubauer1, L. Carone1, A. Hagermann1, C. Stanzel1, B. Häusler2, S. Remus2, J. Selle2, D. Hagl2, D.P. Hinson3, R.A. Simpson3, G.L. Tyler3, S.W. Asmar4, W.I. Axford5, T. Hagfors5, J.-P. Barriot6, J.-C. Cerisier7, T. Imamura8, K.-I. Oyama8, P. Janle9, G. Kirchengast10 & V. Dehant11 1Institut für Geophysik und Meteorologie, Universität zu Köln, D-50923 Köln, Germany Email: [email protected] 2Institut für Raumfahrttechnik, Universität der Bundeswehr München, D-85577 Neubiberg, Germany 3Space, Telecommunication and Radio Science Laboratory, Dept. of Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 95305, USA 4Jet Propulsion Laboratory, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91009, USA 5Max-Planck-Instuitut für Aeronomie, D-37189 Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany 6Observatoire Midi Pyrenees, F-31401 Toulouse, France 7Centre d’etude des Environnements Terrestre et Planetaires (CETP), F-94107 Saint-Maur, France 8Institute of Space & Astronautical Science (ISAS), Sagamihara, Japan 9Institut für Geowissenschaften, Abteilung Geophysik, Universität zu Kiel, D-24118 Kiel, Germany 10Institut für Meteorologie und Geophysik, Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz, A-8010 Graz, Austria 11Observatoire Royal de Belgique, B-1180 Bruxelles, Belgium The Mars Express Orbiter Radio Science (MaRS) experiment will employ radio occultation to (i) sound the neutral martian atmosphere to derive vertical density, pressure and temperature profiles as functions of height to resolutions better than 100 m, (ii) sound -

Exploring the Bombardment History of the Moon

EXPLORING THE BOMBARDMENT HISTORY OF THE MOON Community White Paper to the Planetary Decadal Survey, 2011-2020 September 15, 2009 Primary Author: William F. Bottke Center for Lunar Origin and Evolution (CLOE) NASA Lunar Science Institute at the Southwest Research Institute 1050 Walnut St., Suite 300 Boulder, CO 80302 Tel: (303) 546-6066 [email protected] Co-Authors/Endorsers: Carlton Allen (NASA JSC) Mahesh Anand (Open U., UK) Nadine Barlow (NAU) Donald Bogard (NASA JSC) Gwen Barnes (U. Idaho) Clark Chapman (SwRI) Barbara A. Cohen (NASA MSFC) Ian A. Crawford (Birkbeck College London, UK) Andrew Daga (U. North Dakota) Luke Dones (SwRI) Dean Eppler (NASA JSC) Vera Assis Fernandes (Berkeley Geochronlogy Center and U. Manchester) Bernard H. Foing (SMART-1, ESA RSSD; Dir., Int. Lunar Expl. Work. Group) Lisa R. Gaddis (US Geological Survey) 1 Jim N. Head (Raytheon) Fredrick P. Horz (LZ Technology/ESCG) Brad Jolliff (Washington U., St Louis) Christian Koeberl (U. Vienna, Austria) Michelle Kirchoff (SwRI) David Kring (LPI) Harold F. (Hal) Levison (SwRI) Simone Marchi (U. Padova, Italy) Charles Meyer (NASA JSC) David A. Minton (U. Arizona) Stephen J. Mojzsis (U. Colorado) Clive Neal (U. Notre Dame) Laurence E. Nyquist (NASA JSC) David Nesvorny (SWRI) Anne Peslier (NASA JSC) Noah Petro (GSFC) Carle Pieters (Brown U.) Jeff Plescia (Johns Hopkins U.) Mark Robinson (Arizona State U.) Greg Schmidt (NASA Lunar Science Institute, NASA Ames) Sen. Harrison H. Schmitt (Apollo 17 Astronaut; U. Wisconsin-Madison) John Spray (U. New Brunswick, Canada) Sarah Stewart-Mukhopadhyay (Harvard U.) Timothy Swindle (U. Arizona) Lawrence Taylor (U. Tennessee-Knoxville) Ross Taylor (Australian National U., Australia) Mark Wieczorek (Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, France) Nicolle Zellner (Albion College) Maria Zuber (MIT) 2 The Moon is unique. -

No. 40. the System of Lunar Craters, Quadrant Ii Alice P

NO. 40. THE SYSTEM OF LUNAR CRATERS, QUADRANT II by D. W. G. ARTHUR, ALICE P. AGNIERAY, RUTH A. HORVATH ,tl l C.A. WOOD AND C. R. CHAPMAN \_9 (_ /_) March 14, 1964 ABSTRACT The designation, diameter, position, central-peak information, and state of completeness arc listed for each discernible crater in the second lunar quadrant with a diameter exceeding 3.5 km. The catalog contains more than 2,000 items and is illustrated by a map in 11 sections. his Communication is the second part of The However, since we also have suppressed many Greek System of Lunar Craters, which is a catalog in letters used by these authorities, there was need for four parts of all craters recognizable with reasonable some care in the incorporation of new letters to certainty on photographs and having diameters avoid confusion. Accordingly, the Greek letters greater than 3.5 kilometers. Thus it is a continua- added by us are always different from those that tion of Comm. LPL No. 30 of September 1963. The have been suppressed. Observers who wish may use format is the same except for some minor changes the omitted symbols of Blagg and Miiller without to improve clarity and legibility. The information in fear of ambiguity. the text of Comm. LPL No. 30 therefore applies to The photographic coverage of the second quad- this Communication also. rant is by no means uniform in quality, and certain Some of the minor changes mentioned above phases are not well represented. Thus for small cra- have been introduced because of the particular ters in certain longitudes there are no good determi- nature of the second lunar quadrant, most of which nations of the diameters, and our values are little is covered by the dark areas Mare Imbrium and better than rough estimates. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

Warren and Taylor-2014-In Tog-The Moon-'Author's Personal Copy'.Pdf

This article was originally published in Treatise on Geochemistry, Second Edition published by Elsevier, and the attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author's benefit and for the benefit of the author's institution, for non- commercial research and educational use including without limitation use in instruction at your institution, sending it to specific colleagues who you know, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. All other uses, reproduction and distribution, including without limitation commercial reprints, selling or licensing copies or access, or posting on open internet sites, your personal or institution’s website or repository, are prohibited. For exceptions, permission may be sought for such use through Elsevier's permissions site at: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial Warren P.H., and Taylor G.J. (2014) The Moon. In: Holland H.D. and Turekian K.K. (eds.) Treatise on Geochemistry, Second Edition, vol. 2, pp. 213-250. Oxford: Elsevier. © 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Author's personal copy 2.9 The Moon PH Warren, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA GJ Taylor, University of Hawai‘i, Honolulu, HI, USA ã 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. This article is a revision of the previous edition article by P. H. Warren, volume 1, pp. 559–599, © 2003, Elsevier Ltd. 2.9.1 Introduction: The Lunar Context 213 2.9.2 The Lunar Geochemical Database 214 2.9.2.1 Artificially Acquired Samples 214 2.9.2.2 Lunar Meteorites 214 2.9.2.3 Remote-Sensing Data 215 2.9.3 Mare Volcanism -

Jjmonl 1402.Pmd

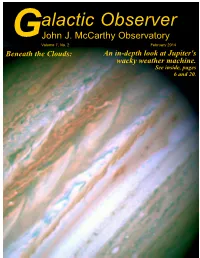

alactic Observer GJohn J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 7, No. 2 February 2014 Beneath the Clouds: An in-depth look at Jupiter's wacky weather machine. See inside, pages 6 and 20. The John J. McCarthy Observatory Galactic Observer New Milford High School Editorial Committee 388 Danbury Road Managing Editor New Milford, CT 06776 Bill Cloutier Phone/Voice: (860) 210-4117 Production & Design Phone/Fax: (860) 354-1595 www.mccarthyobservatory.org Allan Ostergren Website Development JJMO Staff Marc Polansky It is through their efforts that the McCarthy Observatory Technical Support has established itself as a significant educational and Bob Lambert recreational resource within the western Connecticut Dr. Parker Moreland community. Steve Barone Jim Johnstone Colin Campbell Carly KleinStern Dennis Cartolano Bob Lambert Mike Chiarella Roger Moore Route Jeff Chodak Parker Moreland, PhD Bill Cloutier Allan Ostergren Cecilia Dietrich Marc Polansky Dirk Feather Joe Privitera Randy Fender Monty Robson Randy Finden Don Ross John Gebauer Gene Schilling Elaine Green Katie Shusdock Tina Hartzell Jon Wallace Tom Heydenburg Paul Woodell Amy Ziffer In This Issue OUT THE WINDOW ON YOUR LEFT .................................... 4 JUPITER AND ITS MOONS ................................................ 20 SCHILLER TO HANSTEEN .................................................. 5 TRANSIT OF THE JUPITER'S RED SPOT .............................. 17 LRO IMAGES CHANG'E 3 LANDING SITE ........................... 6 SUNRISE AND SUNSET .................................................... -

TRANSIENT LUNAR PHENOMENA: REGULARITY and REALITY Arlin P

The Astrophysical Journal, 697:1–15, 2009 May 20 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/697/1/1 C 2009. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. TRANSIENT LUNAR PHENOMENA: REGULARITY AND REALITY Arlin P. S. Crotts Department of Astronomy, Columbia University, Columbia Astrophysics Laboratory, 550 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027, USA Received 2007 June 27; accepted 2009 February 20; published 2009 April 30 ABSTRACT Transient lunar phenomena (TLPs) have been reported for centuries, but their nature is largely unsettled, and even their existence as a coherent phenomenon is controversial. Nonetheless, TLP data show regularities in the observations; a key question is whether this structure is imposed by processes tied to the lunar surface, or by terrestrial atmospheric or human observer effects. I interrogate an extensive catalog of TLPs to gauge how human factors determine the distribution of TLP reports. The sample is grouped according to variables which should produce differing results if determining factors involve humans, and not reflecting phenomena tied to the lunar surface. Features dependent on human factors can then be excluded. Regardless of how the sample is split, the results are similar: ∼50% of reports originate from near Aristarchus, ∼16% from Plato, ∼6% from recent, major impacts (Copernicus, Kepler, Tycho, and Aristarchus), plus several at Grimaldi. Mare Crisium produces a robust signal in some cases (however, Crisium is too large for a “feature” as defined). TLP count consistency for these features indicates that ∼80% of these may be real. Some commonly reported sites disappear from the robust averages, including Alphonsus, Ross D, and Gassendi. -

Assessment of Spectral Properties of Apollo 12 Landing Site Yann Chemin1, Ian Crawford2, Peter Grindrod2, and Louise Alexander2

Assessment of spectral properties of Apollo 12 landing site Yann Chemin1, Ian Crawford2, Peter Grindrod2, and Louise Alexander2 1Student, Birkbeck Colllege, University of London 2Birkbeck Colllege, University of London Corresponding author: Yann Chemin1 Email address: [email protected] ABSTRACT The geology and mineralogy of the Apollo 12 landing site has been the subject of recent studies that this research attempts to complement from a remote sensing point of view using the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3) sensor data, onboard the Chandrayaan-1 lunar orbiter. It is a higher spatial-spectral resolution sensor than the Clementine UVVis sensor and gives the opportunity to study the lunar surface with a comparatively more detailed spectral resolution. We used ISIS and GRASS GIS to study the M3 data. The M3 signatures are showing a monotonic featureless increment, with very low reflectance, suggesting a mature regolith. The regolith maturity is splitting the landing site in a younger Northwest and older Southeast. The mineral identification using the lunar sample spectra from within the Relab database found some similarity to a basaltic rock/glass mix. The spectrum features of clinopyroxene have been found in the Copernican rays and at the landing site. Lateral mixing increases FeO content away from the central part of the ray. The presence of clinopyroxene in the pigeonite basalt in the stratigraphy of the landing site brings forth some complexity in differentiating the Copernican ray’s clinopyroxene from the local source, as the spectra are twins but for their vertical shift in reflectance, reducing away from the central part of the ray. Spatial variations in mineralogy were not found mostly because of the pixel size compared to the landing site area. -

Alactic Observer Gjohn J

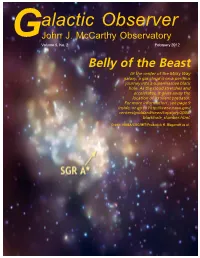

alactic Observer GJohn J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 5, No. 2 February 2012 Belly of the Beast At the center of the Milky Way galaxy, a gas cloud is on a perilous journey into a supermassive black hole. As the cloud stretches and accelerates, it gives away the location of its silent predator. For more information , see page 9 inside, or go to http://www.nasa.gov/ centers/goddard/news/topstory/2008/ blackhole_slumber.html. Credit: NASA/CXC/MIT/Frederick K. Baganoff et al. The John J. McCarthy Observatory Galactic Observvvererer New Milford High School Editorial Committee 388 Danbury Road Managing Editor New Milford, CT 06776 Bill Cloutier Phone/Voice: (860) 210-4117 Production & Design Phone/Fax: (860) 354-1595 Allan Ostergren www.mccarthyobservatory.org Website Development John Gebauer JJMO Staff Marc Polansky It is through their efforts that the McCarthy Observatory has Josh Reynolds established itself as a significant educational and recreational Technical Support resource within the western Connecticut community. Bob Lambert Steve Barone Allan Ostergren Dr. Parker Moreland Colin Campbell Cecilia Page Dennis Cartolano Joe Privitera Mike Chiarella Bruno Ranchy Jeff Chodak Josh Reynolds Route Bill Cloutier Barbara Richards Charles Copple Monty Robson Randy Fender Don Ross John Gebauer Ned Sheehey Elaine Green Gene Schilling Tina Hartzell Diana Shervinskie Tom Heydenburg Katie Shusdock Phil Imbrogno Jon Wallace Bob Lambert Bob Willaum Dr. Parker Moreland Paul Woodell Amy Ziffer In This Issue THE YEAR OF THE SOLAR SYSTEM ................................ 4 SUNRISE AND SUNSET .................................................. 11 OUT THE WINDOW ON YOUR LEFT ............................... 5 ASTRONOMICAL AND HISTORICAL EVENTS ...................... 11 FRA MAURA ................................................................ 5 REFERENCES ON DISTANCES ....................................... -

B. Apollo 16 Regional Geologic Setting

B. APOLLO 16REGIONAL GEOLOGIC SETTING By CARROLL ANN HODGES CONTENTS Page Geography 6 Geologic description of Cayley plains and Descartes mountains 6 Relation in time and space to basins and craters 8 ILLUSTRATIONS Page FIGURE 1. Composite photograph of the lunar near side showing geographic features and multiring basins 7 2. Photographic mosaic of Apollo 16 landing site and vicinity 8 GEOGRAPHY Soderblom and Boyce,1972). The type area of the Cayley Formation is east of the crater Cayley, north of Apollo 16 landed at approximately 15”30’ E., 9” S. on the landing site (Morris and Wilhelms, 1967); the the relatively level Cayley plains, adjacent to the rug- name was extended to the apparently similar plains ged Descartes mountains (Milton, 1972; Hodges, material at the Apollo 16 site (Milton, 1972; Hodges, 1972a). Approximately 70 km east is the west-facing 1972a). These materials were presumed to be represen- escarpment of the Kant plateau, part of the uplifted tative of the widespread photogeologic unit, Imbrian third ring of the Nectaris basin and topographically light plains, which covers about 5 percent of the lunar the highest area on the lunar near side. With respect to highlands surface (Wilhelms and McCauley, 1971; the centers of the three best-developed multiringed Howard and others, 1974). Characteristics include rel- basins, the site is about 600 km west of Nectaris, 1,600 atively level surfaces, intermediate albedo, and nearly km southeast of Imbrium, and 3,500 km east-northeast identical crater size-frequency distributions. of Orientale. The nearest mare materials are in The plains were first interpreted as smooth facies of Tranquillitatis, about 300 km north (fig.1). -

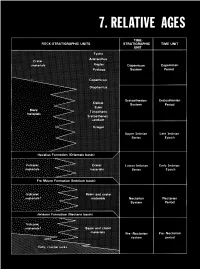

Relative Ages

CONTENTS Page Introduction ...................................................... 123 Stratigraphic nomenclature ........................................ 123 Superpositions ................................................... 125 Mare-crater relations .......................................... 125 Crater-crater relations .......................................... 127 Basin-crater relations .......................................... 127 Mapping conventions .......................................... 127 Crater dating .................................................... 129 General principles ............................................. 129 Size-frequency relations ........................................ 129 Morphology of large craters .................................... 129 Morphology of small craters, by Newell J. Fask .................. 131 D, method .................................................... 133 Summary ........................................................ 133 table 7.1). The first three of these sequences, which are older than INTRODUCTION the visible mare materials, are also dominated internally by the The goals of both terrestrial and lunar stratigraphy are to inte- deposits of basins. The fourth (youngest) sequence consists of mare grate geologic units into a stratigraphic column applicable over the and crater materials. This chapter explains the general methods of whole planet and to calibrate this column with absolute ages. The stratigraphic analysis that are employed in the next six chapters first step in reconstructing