Potential Analysis for Further Nature Conservation in Azerbaijan a Spatial and Political Investment Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Remarks on the Current Efforts for Future Protection of the Kura Water Resources Through Trans-Boundary Cooperation and Modernized National Policy Measures

International Journal of Hydrology Case Report Open Access Some remarks on the current efforts for future protection of the kura water resources through trans-boundary cooperation and modernized national policy measures Abstract Volume 1 Issue 4 - 2017 Azerbaijan locates in the downstream of the Kura river basin. Protection of the bio- Mehman Agarza Oglu Rzayev resources of the Kura River is important for the future welfare and health of the Department of Agricultural Water and Soil, Azerbaijan Scientific- population living in this basin. Therefore coordinated action for the rational use of Production Association of Hydraulic Engineering and Amelioration, the water resources between basin countries is necessary to mitigate main trans- Azerbaijan boundary problems of changes in hydrological flows, worsening of the river water quality, degradation of the ecosystem and intensified flooding due to the observed Correspondence: Mehman Agarza oglu Rzayev, Department consequence of global climate changes taking place in the recent period. This of Agricultural Water and Soil, Azerbaijan Scientific-Production manuscript outlines the proposals within UNDP-GEF Kura - Araz Project ((Kura II Association of Hydraulic Engineering and Amelioration, Project) to improve interaction and cooperation between Azerbaijan and Georgia as a Azerbaijan, Tel +994503246061, Email [email protected] model for future deepening of the relationship between all basin countries to protect fresh water resources and ecological safety of the entire river ecosystem. Received: September 04, 2017 | Published: November 10, 2017 Introduction industrial wastewaters and return flow from agriculture, imposing health, ecological and aesthetic threats. Water pollution takes place Kura River is the main waterway in Caucasus area, originates from due to the mining industry, agriculture and livestock activities starting eastern Turkey, with the total length of 1515 km and inflow to the from the upstream basin countries.4,5 The cooperation between the Caspian Sea through Georgia and Azerbaijan. -

IN BOSNIA and HERZEGOVINA June 2008

RESULTS FROM THE EU BIODIVERSITY STANDARDS SCIENTIFIC COORDINATION GROUP (HD WG) IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA June 2008 RESULTS FROM THE EU BIODIVERSITY STANDARDS SCIENTIFIC COORDINATION GROUP (HD WG) IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 30th June 2008 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 4 2 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON BIH.................................................................. 5 3 IDENTIFIED SOURCES OF INFORMATION ............................................................. 8 3-a Relevant institutions.......................................................................................................................................8 3-b Experts.............................................................................................................................................................9 3-c Relevant scientific publications ...................................................................................................................10 3-c-i) Birds...........................................................................................................................................................10 3-c-ii) Fish ........................................................................................................................................................12 3-c-iii) Mammals ...............................................................................................................................................12 3-c-iv) -

Book Section Reprint the STRUGGLE for TROGLODYTES1

The RELICT HOMINOID INQUIRY 6:33-170 (2017) Book Section Reprint THE STRUGGLE FOR TROGLODYTES1 Boris Porshnev "I have no doubt that some fact may appear fantastic and incredible to many of my readers. For example, did anyone believe in the existence of Ethiopians before seeing any? Isn't anything seen for the first time astounding? How many things are thought possible only after they have been achieved?" (Pliny, Natural History of Animals, Vol. VII, 1) INTRODUCTION BERNARD HEUVELMANS Doctor in Zoological Sciences How did I come to study animals, and from the study of animals known to science, how did I go on to that of still undiscovered animals, and finally, more specifically to that of unknown humans? It's a long story. For me, everything started a long time ago, so long ago that I couldn't say exactly when. Of course it happened gradually. Actually – I have said this often – one is born a zoologist, one does not become one. However, for the discipline to which I finally ended up fully devoting myself, it's different: one becomes a cryptozoologist. Let's specify right now that while Cryptozoology is, etymologically, "the science of hidden animals", it is in practice the study and research of animal species whose existence, for lack of a specimen or of sufficient anatomical fragments, has not been officially recognized. I should clarify what I mean when I say "one is born a zoologist. Such a congenital vocation would imply some genetic process, such as that which leads to a lineage of musicians or mathematicians. -

A Study on Fauna of the Shahdagh National Park

J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. , 5(10)11-15, 2015 ISSN: 2090-4274 Journal of Applied Environmental © 2015, TextRoad Publication and Biological Sciences www.textroad.com A Study on fauna of the Shahdagh National Park S.M. Guliyev Institute of Zoology of Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences, Pass.1128, block 504, Baku, AZ 1073, Azerbaijan Received: June 2, 2015 Accepted: August 27, 2015 ABSTRACT The paper contains information about mammals and insects entered the Red Book of Azerbaijanand the Red List of IUCN distributed in the Azerbaijan territories of the Greater Caucasus (South and North slopes). Researche carried out in the 2008-2012 years. It can be noted that from 43 species of mammals and 76 species of insects entering the Red Book of Azerbaijan 23 ones of mammals ( Rhinolophus hipposideros Bechstein, 1800, Myotis bechsteinii Kunhl, 1817, M.emarqinatus Geoffroy, 1806, M.blythii Tomas, 1875, Barbastella barbastella Scheber, 1774, Barbastella leucomelas Cretzchmar, 1826, Eptesicus bottae Peters, 1869, Hystrix indica Kerr, 1792, Micromys minutus Pollas, 1771, Chionomys gud Satunin,1909, Hyaena hyaena Linnaeus, 1758, Ursus arctos (Linnaeus, 1758), Martes martes (Linnaeus, 1758), Mustela (Mustela) erminea , 1758, Lutra lutra (Linnaeus, 1758), Telus (Chaus) Chaus Gued., 1776, Lynx lynx (Linnaeus, 1758), Pantherapardus (Linnaeus, 1758), Rupicara rupicapra (Linnaeus, 1758), Capreolus capreolus (Linnaeus, 1758), Cervus elaphus maral (Ogilbi, 1840), Capra cylindricornis Bulth, 1840) and 15 species of insects ( Carabus (Procerus) caucasicus -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

Annex I List of Species and Habitats

Annex I List of species and habitats No. Appendix II species Gornja Gornja Ulog Other source and Neretva Neretva EIA notes Phase 1 EIA Phase 2 EIA 1. Canis lupus p 58, pp 59-62 p 58 p 52 Emerald – Standard Data Form 2. Ursus arctos (Ursidae) p 58, pp 59-62 p 58 p 52 Emerald – Standard Data Form 3. 1 Lutra lutra p 58 p 58 - 4. Euphydryas aurinia p 59-62 p 57 - Emerald – Standard Data Form 5. 2 Phengaris arion (Maculinea p 59-62 p 57 - arion) 6. Bombina variegata p 57 p 55 - Herpetoloska baza BHHU:ATRA Emerald – Standard Data Form 7. Hyla arborea - - - Herpetoloska baza BHHU:ATRA 8. Rana Dalmatina - - - Herpetoloska baza BHHU:ATRA 9. 3 Bufotes viridis - - - Herpetoloska baza BHHU:ATRA 10. Lacerta agilis p 57 p 55 - 11. Lacerta viridis p 57 p 55 - 12. Natrix tessellata p 57 p 55 - 13. Vipera ammodytes - - - Herpetoloska baza BHHU: ATRA 14. Zamenis longissimus (as - - - Herpetoloska baza Elaphe longissima) BHHU: ATRA 15. Coronella austriaca - - - Herpetoloska baza BHHU: ATRA 16. Algyroides nigropunctatus - - - Herpetoloska baza BHHU: ATRA 17. 4 Podarcis melisellensis - - - Herpetoloska baza BHHU: ATRA 18. Cerambyx cerdo pp 59-62 p 58 - Emerald – Standard Data Form 19. Anthus trivialis p 57 p 55 - (Motacillidae) 20. Carduelis cannabina p 57 p 55 - 21. Carduelis carduelis p 57 p 55 - 1 The description of fauna in the EIAs for species 1, 2 and 3 is based on the local hunting documentation, on species likely to be present in such habitats, and on a description of species mentioned in the project undertaken to establish the Emerald network in BIH. -

Response Variations of Alnus Subcordata (L.), Populus Deltoides (Bartr

Taiwan J For Sci 27(3): 251-63, 2012 251 Research paper Response Variations of Alnus subcordata (L.), Populus deltoides (Bartr. ex Marsh.), and Taxodium distichum (L.) Seedlings to Flooding Stress Ehsán Ghanbary,1) Masoud Tabari,1,4) Francisco García-Sánchez,2) Mehrdad Zarafshar,1) Maria Cristina Sanches3) 【Summary】 Alnus subcordata is a native species distributed along bottomlands of Hyrcanian forests of northern Iran. In the last decade, this species along with the exotic species Populus deltoides and Taxodium distichum, has been widely used also for afforestation of bottomland areas. However, the relative flooding tolerance of these 3 species and their potential mechanisms for coping with flooding conditions are unknown to the present. Thus, in this study, variations in growth and mor- phophysiological responses to flooding of these species’ seedlings were investigated during a 120- d outdoor experiment. Seedlings were subjected to 3 fixed treatments of 1) unflooded, 2) flooded to 3 cm in depth, and 3) flooded to 15 cm in depth, and their survival, growth, and some metabolic parameters were measured at the end of the experiment. Survival in seedlings of these 3 species was very high, but the root length, biomass accumulation, and chlorophyll content were reduced by flooding. Diameter growth in T. distichum increased with flooding, while it was negatively affected in the other 2 species. The leaf area, specific leaf area, and height growth were reduced in A. sub- cordata and P. deltoides by flooding, while no significant effect on these parameters was observed in T. distichum. Flooding also induced the formation of hypertrophied lenticels, and adventitious roots in all 3 species. -

Global Survey of Ex Situ Betulaceae Collections Global Survey of Ex Situ Betulaceae Collections

Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections By Emily Beech, Kirsty Shaw and Meirion Jones June 2015 Recommended citation: Beech, E., Shaw, K., & Jones, M. 2015. Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections. BGCI. Acknowledgements BGCI gratefully acknowledges the many botanic gardens around the world that have contributed data to this survey (a full list of contributing gardens is provided in Annex 2). BGCI would also like to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in the promotion of the survey and the collection of data, including the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, Yorkshire Arboretum, University of Liverpool Ness Botanic Gardens, and Stone Lane Gardens & Arboretum (U.K.), and the Morton Arboretum (U.S.A). We would also like to thank contributors to The Red List of Betulaceae, which was a precursor to this ex situ survey. BOTANIC GARDENS CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL (BGCI) BGCI is a membership organization linking botanic gardens is over 100 countries in a shared commitment to biodiversity conservation, sustainable use and environmental education. BGCI aims to mobilize botanic gardens and work with partners to secure plant diversity for the well-being of people and the planet. BGCI provides the Secretariat for the IUCN/SSC Global Tree Specialist Group. www.bgci.org FAUNA & FLORA INTERNATIONAL (FFI) FFI, founded in 1903 and the world’s oldest international conservation organization, acts to conserve threatened species and ecosystems worldwide, choosing solutions that are sustainable, based on sound science and take account of human needs. www.fauna-flora.org GLOBAL TREES CAMPAIGN (GTC) GTC is undertaken through a partnership between BGCI and FFI, working with a wide range of other organisations around the world, to save the world’s most threated trees and the habitats which they grow through the provision of information, delivery of conservation action and support for sustainable use. -

Bağbahçe Bilim Dergisi

b 10.35163/bagbahce.899831 8(2) 2021: 43-55 b E-ISSN: 2148-4015 Bağbahçe Bilim Dergisi b http://edergi.ngbb.org.tr Araştırma Makalesi Azerbaycan Cumhuriyetinin Hirkan Florasının Dendroflorası Ve Bazı Türlerin Dendrokronolojik İncelemesi Bagırova Samire 1*, Hasanova Minare 2, Rasulova Aydan 3, Atayeva Leyla 4, Shukurova Nurlane 5 1Azerbaycan Ulusal Bilimler Akademisi Dendroloji Enstitüsü, PHd (Bilimsel İşler Müdür Yardımcısı), Azerbaycan 2Azerbaycan Ulusal Bilimler Akademisi, Dendroloji Enstitüsü (Bilimsel Sekreter), Azerbaycan 3Azerbaycan Ulusal Bilimler Akademisi, Dendroloji Enstitüsü (Asistan), Azerbaycan 3Azerbaycan Ulusal Devlet Pedagoji Üniversitesi (Tyutor-Özel Öyretmen), Azerbaycan *Sorumlu yazar / Correspondence: [email protected] Geliş/Received: 06.04.2021 • Kabul/Accepted: 26.08.2021 • Yayın/Published Online: 31.08.2021 Öz: Bu çalışmada Azerbaycan Cumhuriyeti’nde rölyefi, bitki örtüsü ve toprak örtüsünde farklılık gösteren Hirkan Bölgesi’ndeki Hirkan Milli Parkı'nın dendroflorası izlenmiş, bitki türleri belirlenmiş, taksonomik liste hazırlanmış ve dendrokronolojik özellikler araştırılmıştır. Çalışma alanı florasında 7 çalı oluşumlu 7 birlik tespit edilmiştir. 21 cinse ait 54 ağaç ve çalı türünden 11 tohum ve 86 herbaryum örneği 28 farklı alandan toplanarak laboratuvar koşullarında hazırlanmıştır. Herbaryum materyallerinin teşhisinde çeşitli referanslar kullanılmıştır. Toplanan herbaryumlar, Engler ve APG III-IV sistemleri temelinde incelenmiş, "herbaryum" ve "tohum" fonuna eklenmiştir. Dendrokronolojik çalışmaların -

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan PR E S I D E N T I a L L I B R a R Y National Parks N

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- National Parks National parks are the public lands or bodies of water of special environmental, historical and other importance, which bear the status of governmental institutions. They serve to the purposes of environmental protection, educational, scientific, cultural researches, etc. protecting environment and serving the educational, scientific, cultural and other purposes. Name: Hirkan National Park Year of foundation: 2004 Area (hectare): 21435 Location: Within the territory of Lankaran and Astara administrative districts. Brief description: The Hirkan National Park is in Lankaran natural region and protects the landscapes of humid subtropics. The Hirkan National Park consists of valley area of Lankaran lowland and mountainous landscape of Talysh Mountains. The Lankaran natural region has rich fauna and flora including many rare and endemic species. Flora of the park consists of 1, 900 species including 162 endemic, 95 rare and 38 endangered -

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

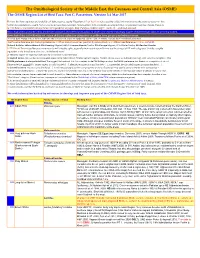

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION.