Becoming One of the Most Valuable New Venture in the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovating and Entrepreneurial Initiatives: Some Cases of Success

Volume 14, 2017 INNOVATING AND ENTREPRENEURIAL INITIATIVES: SOME CASES OF SUCCESS Marta Machín-Martínez Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, [email protected] Madrid, Spain Carmen de-Pablos-Heredero* Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, [email protected] Madrid, Spain * Corresponding author ABSTRACT Aim/Purpose To understand the change of entrepreneurial initiatives by analysing some new initiatives that came up the last years based on IT enabled business models Background The theme is described from an educational perspective by offering examples of successful entrepreneurship initiatives Methodology Description of some cases: Waynabox, Lock up, Uber, Pinterest Contribution This project tries to become a guide for youth in order to understand various aspects: first, the entrepreneurial aspects that have to be considered before starting a business; secondly, the characteristics that successful businesses have in common; and finally how an entrepreneur can be innovative and how they can achieve the success Findings Only the 10% of the start-ups exist more than three years. Among the causes of failure are the high saturation of the market and the market competition, which are connected to the ignorance of the real necessity of customers. The company has to identify the needs of customers. They have to define and target their customers by observing and analyzing the market and, above all, getting in touch with the customers. The business plan is something that has to be carried out before the beginning of the project, and has to exist on paper. Everything has to be planned and organised, and the objectives have to be clearly stated in order to stay focused Recommendations To use existent business models as an inspiration for the creation of a new for Practitioners business model. -

Music's Augmented Future

thereport ISSUE 410 | 17 OCTOBER 2017 Music’s augmented future 1 ISSUE 410 17.10.17 COVERAR SPECIAL FEATURE PART 1 AR you experienced? he first thing to understand about Cycle report alongside technologies like Kingston; in the years since there have been particularly around its potential to become augmented reality (AR) technology microblogging, social networking platforms a steady stream of experiments around music truly mainstream. There are several reasons is that while it may be a hot trend of and 3D printing. and AR. You can read about some of them for this, starting with 2016’s big app craze: 2017, it’s certainly not a new trend. 2008 was also the year when Apple and later in this issue. Pokémon Go (pictured). TSci-fi author William Gibson was writing Google launched their first app stores for In the years after 2008, many of these While catching virtual beasties in real- about the idea of augmenting humans’ vision smartphones, with startups like Layar and campaigns have, with hindsight (and often world locations also seemed gimmicky at first with digital content in 1994, although arguably Metaio early to experiment with “browser” even at the time) seemed like gimmicks; – the mobile game raced to $500m of revenue head-up displays (HUDs) in aircraft were the apps that overlaid information onto the good for getting a few headlines when they and then $1bn. Even in April 2017, there were first example of AR decades before that. phone’s camera feed. launched, then quickly forgotten with no still 65m active players globally, and for many report AR as we understand it in 2017 has been By 2009, Music Ally was writing about AR obvious impact on sales or fan engagement. -

The Uber Board Deliberates: Is Good Governance Worth the Firing of an Entrepreneurial Founder? by BRUCE KOGUT *

ID#190414 CU242 PUBLISHED ON MAY 13, 2019 The Uber Board Deliberates: Is Good Governance Worth the Firing of an Entrepreneurial Founder? BY BRUCE KOGUT * Introduction Uber Technologies, the privately held ride-sharing service and logistics platform, suffered a series of PR crises during 2017 that culminated in the resignation of Travis Kalanick, cofounder and longtime CEO. Kalanick was an acclaimed entrepreneur, building Uber from its local San Francisco roots to a worldwide enterprise in eight years, but he was also a habitual rule- breaker. 1 In an effort to put the recent past behind the company, the directors of Uber scheduled a board meeting for October 3, 2017, to vote on critical proposals from new CEO Dara Khosrowshahi that were focused essentially on one question: How should Uber be governed now that Kalanick had stepped down as CEO? Under Kalanick, Uber had grown to an estimated $69 billion in value by 2017, though plagued by scandal. The firm was accused of price gouging, false advertising, illegal operations, IP theft, sexual harassment cover-ups, and more.2 As Uber’s legal and PR turmoil increased, Kalanick was forced to resign as CEO, while retaining his directorship position on the nine- member board. His June 2017 resignation was hoped to calm the uproar, but it instead increased investor uncertainty. Some of the firm’s venture capital shareholders (VCs) marked down their Uber holdings by 15% (Vanguard, Principal Financial), while others raised the valuation by 10% (BlackRock).3 To restore Uber’s reputation and stabilize investor confidence, the board in August 2017 unanimously elected Dara Khosrowshahi as Uber’s next CEO. -

Download Book

0111001001101011 01THE00101010100 0111001001101001 010PSYHOLOGY0111 011100OF01011100 010010010011010 0110011SILION011 01VALLEY01101001 ETHICAL THREATS AND EMOTIONAL UNINTELLIGENCE 01001001001110IN THE TECH INDUSTRY 10 0100100100KATY COOK 110110 0110011011100011 The Psychology of Silicon Valley “As someone who has studied the impact of technology since the early 1980s I am appalled at how psychological principles are being used as part of the busi- ness model of many tech companies. More and more often I see behaviorism at work in attempting to lure brains to a site or app and to keep them coming back day after day. This book exposes these practices and offers readers a glimpse behind the “emotional scenes” as tech companies come out psychologically fir- ing at their consumers. Unless these practices are exposed and made public, tech companies will continue to shape our brains and not in a good way.” —Larry D. Rosen, Professor Emeritus of Psychology, author of 7 books including The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High Tech World “The Psychology of Silicon Valley is a remarkable story of an industry’s shift from idealism to narcissism and even sociopathy. But deep cracks are showing in the Valley’s mantra of ‘we know better than you.’ Katy Cook’s engaging read has a message that needs to be heard now.” —Richard Freed, author of Wired Child “A welcome journey through the mind of the world’s most influential industry at a time when understanding Silicon Valley’s motivations, myths, and ethics are vitally important.” —Scott Galloway, Professor of Marketing, NYU and author of The Algebra of Happiness and The Four Katy Cook The Psychology of Silicon Valley Ethical Threats and Emotional Unintelligence in the Tech Industry Katy Cook Centre for Technology Awareness London, UK ISBN 978-3-030-27363-7 ISBN 978-3-030-27364-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27364-4 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020 This book is an open access publication. -

2020 Philadelphia Venture Report

2020 PHILADELPHIA VENTURE REPORT Data provided by WE HELP BREAKTHROUGH IDEAS ACTUALLY BREAK THROUGH. We believe in the risk takers, the game-changers and the disruptors—those who committed to leveraging innovation to make the world a better place. Bridge Bank, founded in 2001 in Silicon Valley, serves small-market and middle-market businesses across many industries, as well as emerging technology and life sciences companies and the private equity community. Geared to serving both venture-backed and non-venture-backed companies across all stages of growth, Bridge Bank offers a broad scope of financial solutions including growth capital, equipment and working capital credit facilities, venture debt, treasury management, asset-based lending, SBA and commercial real estate loans, ESOP finance and full line of international products and services. To learn more about us, visit info.bridgebank.com/tech-innovation. Matt Klinger Brian McCabe Senior Director, Technology Banking Senior Director, Technology Banking [email protected] [email protected] (703) 547-8198 (703) 345-9307 Bridge Bank, a division of Western Alliance Bank. Member FDIC. *All offers of credit are subject to approval. Introduction 2020 was a watershed moment on so many fronts. The COVID-19 pandemic will forever change how we live, work, and interact. The killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and countless others have brought focus and urgency to attacking racism, racial injustice, and the resulting inequities in our society. Philadelphia has always been a city fueled by passion and determination to challenge the status quo, think differently, invent, and push forward together. This report showcases the fruits of that passion in the form of capital raised to fuel innovation. -

Game-Tech-Whitepaper

Type & Color October, 2020 INSIGHTS Game Tech How Technology is Transforming Gaming, Esports and Online Gambling Elena Marcus, Partner Sean Tucker, Partner Jonathan Weibrecht,AGC Partners Partner TableType of& ContentsColor 1 Game Tech Defined & Market Overview 2 Game Development Tools Landscape & Segment Overview 3 Online Gambling & Esports Landscape & Segment Overview 4 Public Comps & Investment Trends 5 Appendix a) Game Tech M&A Activity 2015 to 2020 YTD b) Game Tech Private Placement Activity 2015 to 2020 YTD c) AGC Update AGCAGC Partners Partners 2 ExecutiveType & Color Summary During the COVID-19 pandemic, as people are self-isolating and socially distancing, online and mobile entertainment is booming: gaming, esports, and online gambling . According to Newzoo, the global games market is expected to reach $159B in revenue in 2020, up 9.3% versus 5.3% growth in 2019, a substantial acceleration for a market this large. Mobile gaming continues to grow at an even faster pace and is expected to reach $77B in 2020, up 13.3% YoY . According to Research and Markets, the global online gambling market is expected to grow to $66 billion in 2020, an increase of 13.2% vs. 2019 spurred by the COVID-19 crisis . Esports is projected to generate $974M of revenue globally in 2020 according to Newzoo. This represents an increase of 2.5% vs. 2019. Growth was muted by the cancellation of live events; however, the explosion in online engagement bodes well for the future Tectonic shifts in technology and continued innovation have enabled access to personalized digital content anywhere . Gaming and entertainment technologies has experienced amazing advances in the past few years with billions of dollars invested in virtual and augmented reality, 3D computer graphics, GPU and CPU processing power, and real time immersive experiences Numerous disruptors are shaking up the market . -

FORBES 30 Under

The rugged and revolutionary Olympus OM-D E-M1. No matter where life’s INTRODUCING A CAMERA adventures take you, the Olympus OM-D E-M1 can always be by your side. Its AS RUGGED magnesium alloy body is dustproof, splashproof, and freezeproof, so it’ll survive the harshest of conditions. And the super-fast and durable 1/8000s mechanical AS YOU ARE. shutter and 10 fps sequential shooting will capture your entire journey exactly the way you experienced it. www.getolympus.com/em1 Move into a New World ÒThe OM-D lets me get great shots because itÕs rugged and durable. In this shot, I was shooting when the dust was the thickest because it enhanced the light. I even changed lenses and IÕve yet to have a dust problem with my OM-D system.Ó -Jay Dickman, Olympus Visionary Shot with an OM-D, M.ZUIKO ED 75-300mm f4.8-6.7 II • One of the smallest and lightest bodies in its class at 17.5 ounces* • Built-in Wi-Fi • Full system of premium, interchangeable lenses *E-M1 body only contents — JAnUARY 20, 2014 VOLUME 193 NUMBER 1 30 FORBES 30 UNDER 88 | NEXT-GENERATION ENTREPRENEURS Four hundred and f fty faces of the future. 11 | FACT & COMMENT BY STEVE FORBES The lies continue. LEADERBOARD 14 | SCORECARD 2013: a very good year. 16 | BEING REED HASTINGS The man running the show at Netfl ix has a story that any screenwriter would be proud of. 18 | THE YEAR’S HOTTEST STARTUPS A panel of VCs and entrepreneurs selected these businesses from more than 300 contenders. -

Oklahoma City Employee Retirement System

Oklahoma City Employee Retirement System Comprehensive Annual Financial Report | A Pension Trust Fund of Oklahoma City The City of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma | for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 2019 and 2020 OKLAHOMA CITY EMPLOYEE RETIREMENT SYSTEM A Pension Trust Fund of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Board of Trustees Paul Bronson, Chairman Ken Culver, Vice-Chairman Frances Kersey, Secretary (ex-officio) Matthew Boggs, Treasurer (ex-officio) Karla Nickels Aimee Maddera Brent Bryant Jacqueline Ames Jim Williamson JC Reiss Randy Thurman Vacant Eugene (Marty) Lawson Management Regina Story, Administrator Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Years Ended June 30, 2020 and 2019 Prepared by The Oklahoma City Finance Department, Accounting Services Division Angela Pierce, CPA, Assistant Finance Director / Controller OKLAHOMA CITY EMPLOYEE RETIREMENT SYSTEM TABLE OF CONTENTS For the Fiscal Years Ended June 30, 2020 and 2019 PAGE I. INTRODUCTORY SECTION Transmittal Letter 1 Certificate of Achievement for Excellence in Financial Reporting 5 Public Pension Standards Award for Funding and Administration 6 Board of Trustees 7 Professional Services 8 Organization Chart 9 Report of the Chair 10 II. FINANCIAL SECTION Independent Auditor's Report on Financial Statements and Supplementary Information 11 Management's Discussion and Analysis 13 Basic Financial Statements: Statements of Fiduciary Net Position 17 Statements of Changes in Fiduciary Net Position 18 Notes to Financial Statements 19 Required Supplementary Information: Defined Benefit Pension -

Introduction to Business Models Dr

Introduction to Business Models Dr. Jack M. Wilson, Distinguished Professor of Higher Education, Emerging Technologies, and Innovation Entrepreneurship: Principles © 2012 ff -Jack M. Wilson Distinguished Professor Introduction to Business Models - 1 References: • Chapter 6: Beyond Entrepreneurship; Jack M. Wilson; – http://www.jackmwilson.net/Entrepreneurship/Principles/6-BeyondEntrepreneurship-BusinessModels.pdf • Chapter 16: Innovation and Entrepreneurship 3rd Edition; John Bessant and Joe Tidd; Wiley; United Kingdom; 2015. • Chapter 4: Startup Opportunities 2nd Edition; Sean Wise & Brad Feld; Wiley; Hoboken, NJ; 2017. • Uber: – http://www.jackmwilson.net/Entrepreneurship/Cases/Case-Uber.pdf – http://www.businessofapps.com/uber-usage-statistics-and-revenue/ • Segway: – http://www.jackmwilson.net/Entrepreneurship/Cases/Case-Segway%20Case.pdf • Privo: – http://www.jackmwilson.net/Entrepreneurship/Cases/Case-Privo.pdf • Dell: – http://www.jackmwilson.net/Entrepreneurship/Cases/Case-Dell.pdf • Wikipedia: Business Model: – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Business_model Entrepreneurship: Principles © 2012 ff -Jack M. Wilson Distinguished Professor Introduction to Business Models - 2 Consider the case of Uber • History – Founded in 2009 by Garrett Camp and Travis Kalanick as “UberCab” – Met at LeWeb in Paris, France in 2008, Camp wanted to solve the Taxi problem in San Francisco – Original pitch split the cost of a driver, Mercedes S Class, and a parking spot with an iPhone app – January 2010, service was first tested in New York – Service launched in July 2010 in San Francisco – From May 2011 to February 2012 Uber expanded into Seattle, Boston, New York, Chicago, and Washington D.C. – First international expansion in Paris, France in December 2011 Entrepreneurship: Principles © 2012 ff -Jack M. Wilson Distinguished Professor Introduction to Business Models - 3 Founders • Garrett Camp • Travis Kalanick – Graduate from University of – Dropped out of UCLA in 1998, Calgary, Bachelors in Electrical founded Scour Inc. -

The Spectacles Opportunity

Snap Inc. The Spectacles Opportunity CENTRAL QUESTION What is Snap’s position in the wearables and augmented reality space? Question: What is Snap’s position in the wearables and augmented reality space? Snap may have started as a photo disappearing app in the convergence of wearables and augmented reality (AR). It’s 2011, but the company now has the potential to reinvent how clear the wearables and AR markets are gaining momentum as people use the camera. Now a public company, Snap must quell evidenced by the growth in wearable offerings and AR Wall Street’s demands while also competing against established development kits released recently. As the market and tech mature social media giants for revenue. The market expects nothing short over the years, Snap is strategically positioned to bring AR of flawless execution from 6-year-old Snap Inc. spectacles to the mass consumer market. Despite short-term stress, Snap’s position is envious. Its core With the release of seemingly unambitious Spectacles, Snap product, Snapchat, enjoys high engagement with a young, has ingeniously dipped into wearables without upsetting lucrative demographic that evades advertisers through traditional consumers. Spectacles offer little beyond Snapchat’s core usage. avenues like television. More importantly, despite competitors’ However, as Snapchat begins to introduce and become associated willingness to copy offerings, Snapchat is unique in its offerings to with AR, the gradual convergence of Snapchat’s AR offerings onto both users and advertisers. Snapchat’s competitive advantage is Spectacles will open up the possibility of mainstream adoption. not only its high quantity of engagement but also the quality of Snap’s product development shows it is swiftly striving engagement afforded by the camera. -

Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms

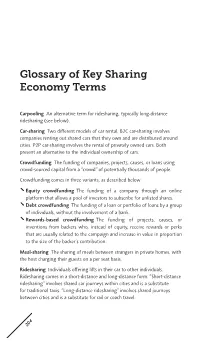

Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms Carpooling An alternative term for ridesharing, typically long-distance ridesharing (see below). Car-sharing Two different models of car rental. B2C car-sharing involves companies renting out shared cars that they own and are distributed around cities. P2P car-sharing involves the rental of privately owned cars. Both present an alternative to the individual ownership of cars. Crowdfunding The funding of companies, projects, causes, or loans using crowd-sourced capital from a “crowd” of potentially thousands of people. Crowdfunding comes in three variants, as described below. Equity crowdfunding The funding of a company through an online platform that allows a pool of investors to subscribe for unlisted shares. Debt crowdfunding The funding of a loan or portfolio of loans by a group of individuals, without the involvement of a bank. Rewards-based crowdfunding The funding of projects, causes, or inventions from backers who, instead of equity, receive rewards or perks that are usually related to the campaign and increase in value in proportion to the size of the backer’s contribution. Meal-sharing The sharing of meals between strangers in private homes, with the host charging their guests on a per seat basis. Ridesharing Individuals offering lifts in their car to other individuals. Ridesharing comes in a short-distance and long-distance form. “Short-distance ridesharing” involves shared car journeys within cities and is a substitute for traditional taxis. “Long-distance ridesharing” involves shared journeys between cities and is a substitute for rail or coach travel. 204 Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms 205 Sharing economy (condensed version) The value in taking underutilized assets and making them accessible online to a community, leading to a reduced need for ownership of those assets. -

The Airbnb Story – Page 1

The Airbnb Story – Page 1 THE AIRBNB STORY How Three Ordinary Guys Disrupted an Industry, Made Billions...and Created Plenty of Controversy LEIGH GALLAGHER LEIGH GALLAGHERis an assistant managing editor at Fortune where she writes and edits feature stories. She is also the host of Fortune Live, Fortune.com's weekly video show. Leigh Gallagher is a co-chair of the Fortune Most Powerful Women Summit and also oversees Fortune's 40 Under 40 multi-platform editorial franchise. She appears regularly as a business news commentator on many TV shows including CBS's This Morning and Face the Nation, public radio's Marketplace, MSNBC's Morning Joe, CNBC and CNN. She is the author of two books including The End of the Suburbs and is a visiting scholar at New York University. She is a graduate of Cornell University. ISBN 978-1-77544-909-6 SUMMARIES.COM empowers you to get 100% of the ideas from an entire business book for 10% of the cost and in 5% of the time. Hundreds of business books summarized since 1995 and ready for immediate use. Read less, do more. www.summaries.com The Airbnb Story – Page 1 1. Looking for the next big thing design blogs they knew all the attendees would be assumption these conferences could easily max out a reading. They refined this idea for weeks, and the more hotel's supply of rooms and they decided the perfect they talked about it, the more they realized it was so place to launch would be for the upcoming South by The Airbnb story began in Providence, Rhode Island in weird that it just might work—and with a looming Southwest conference in Austin, Texas.