Production: Produced by Members of the Berkeley Technology Law Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vumber Gives You Throw-Away Phone Numbers for Dating, Work

Tech Gadgets Mobile Enterprise GreenTech CrunchBase TechCrunch TV The Crunchies More Search What's Hot: Android Apple Facebook Google Groupon Microsoft Twitter Zynga Classics Subscribe: Got a tip? Building a startup? Tell us NOW TWEET THIS AUTHENTIC? Google Teams Up With Facebook Has Been Refining KEEN ON... Twitter And SayNow To Bring Their Troll-Slaying Comment Exposed: Apple's Terrible Sin Tweeting-By-Phone To Egypt System For Months; Finally in China » » Ready To Roll? » Err, Call Me: Vumber Gives You Throw-Away Phone Numbers For Dating, Work Jason Kincaid Tweet Most Popular 14 minutes ago View Comments Now Commented Facebook By now you’ve probably heard of Google Voice, a service that lets you take Exposed: Apple’s Terrible Sin in one phone number and configure it to ring all of your phones — work, China (TCTV) mobile, home, whatever — with plenty of settings to manage your inbound and outbound calls. But what if you wanted the opposite: a service that lets Should You Really Be A Startup you spawn a multitude of phone numbers to be used and discarded at your Entrepreneur? leisure? That’s where Vumber comes in. When The Drones Come Marching In The service has actually been around for four years, but it was originally 4chan Founder Unleashes Canvas marketed exclusively toward people on dating sites. The use case is On The World obvious: instead of handing out your real phone number to strangers, Instructure Launches To Root Vumber lets you spin up a new phone number, which you then redirect to Blackboard Out Of Universities your real phone. -

JULIAN ASSANGE: When Google Met Wikileaks

JULIAN ASSANGE JULIAN +OR Books Email Images Behind Google’s image as the over-friendly giant of global tech when.google.met.wikileaks.org Nobody wants to acknowledge that Google has grown big and bad. But it has. Schmidt’s tenure as CEO saw Google integrate with the shadiest of US power structures as it expanded into a geographically invasive megacorporation... Google is watching you when.google.met.wikileaks.org As Google enlarges its industrial surveillance cone to cover the majority of the world’s / WikiLeaks population... Google was accepting NSA money to the tune of... WHEN GOOGLE MET WIKILEAKS GOOGLE WHEN When Google Met WikiLeaks Google spends more on Washington lobbying than leading military contractors when.google.met.wikileaks.org WikiLeaks Search I’m Feeling Evil Google entered the lobbying rankings above military aerospace giant Lockheed Martin, with a total of $18.2 million spent in 2012. Boeing and Northrop Grumman also came below the tech… Transcript of secret meeting between Julian Assange and Google’s Eric Schmidt... wikileaks.org/Transcript-Meeting-Assange-Schmidt.html Assange: We wouldn’t mind a leak from Google, which would be, I think, probably all the Patriot Act requests... Schmidt: Which would be [whispers] illegal... Assange: Tell your general counsel to argue... Eric Schmidt and the State Department-Google nexus when.google.met.wikileaks.org It was at this point that I realized that Eric Schmidt might not have been an emissary of Google alone... the delegation was one part Google, three parts US foreign-policy establishment... We called the State Department front desk and told them that Julian Assange wanted to have a conversation with Hillary Clinton... -

Paying for the Party

PX_PARTY_HDS:PX_PARTY_HDS 16/4/08 11:48 Page 1 Paying for the Party Myths and realities in British political finance Michael Pinto-Duschinsky edited by Roger Gough Policy Exchange is an independent think tank whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas which will foster a free society based on strong communities, personal freedom, limited government, national self-confidence and an enterprise culture. Registered charity no: 1096300. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development. We work in partnership with aca- demics and other experts and commission major studies involving thorough empirical research of alternative policy out- comes. We believe that the policy experience of other countries offers important lessons for government in the UK. We also believe that government has much to learn from business and the voluntary sector. Tru, stees Charles Moore (Chairman of the Board), Theodore Agnew, Richard Briance, Camilla Cavendish, Robin Edwards, Richard Ehrman, Virginia Fraser, Lizzie Noel, George Robinson, Andrew Sells, Tim Steel, Alice Thomson, Rachel Whetstone PX_PARTY_HDS:PX_PARTY_HDS 16/4/08 11:48 Page 2 About the author Dr Michael Pinto-Duschinsky is senior Nations, the European Union, Council of research fellow at Brunel University and a Europe, Commonwealth Secretariat, the recognised worldwide authority on politi- British Foreign and Commonwealth cal finance. A former fellow of Merton Office and the Home Office. He was a College, Oxford, and Pembroke College, founder governor of the Westminster Oxford, he is president of the International Foundation for Democracy. In 2006-07 he Political Science Association’s research was the lead witness before the Committee committee on political finance and politi- on Standards in Public Life in its review of cal corruption and a board member of the the Electoral Commission. -

Netflix Ecosystem Phone: (408) 540-3700

Netflix 100 Winchester Circle Los Gatos, CA 95032 Netflix Ecosystem Phone: (408) 540-3700 www.netflix.com Outside Relationships (a California Corporation) Outside Relationships Netflix Securities Regulation Regulators Capital Suppliers Customers and Stock Exchange Customers Suppliers Capital Regulators Debt Structure Equity Structure Listing Rules Public Debt Bond Financing Holders Debt ( $16.31 Billion as of December 31, 2020) | Credit Ratings: S&P (BB+), Moody’s (Ba3) Equity Securities Common Stock Regulators $750 Million Revolving Credit Facility (Matures 2024) 2021 Senior Notes ($500 Million) 2025 Senior Notes ($800 Million) 2027 Senior Notes ($1.588 Billion) Common Stock Repurchase Plan Preferred Stock Common Stock Repurchases Significant Authorized: $5 Billion Authorized: 10,000,000 Authorized: 4,990,000,000 Shareholders Deposit Accounts with Black-Owned Financial Institutions 2022 Senior Notes ($700 Million) 2025 Senior Notes ($500 Million) 2028 Senior Notes ($1.600 Billion) US Securities Balance Available: $5 Billion Issued: None Issued: 442,895,261 Revolving Credit Financing Equity Capital and Exchange Commercial Black Economic Development Initiative Hope Credit Union 2024 Senior Notes ($400 Million) 2026 Senior Notes ($1.00 Billion) 2028 Senior Notes ($1.900 Billion) Expiration: None Record Holders: None Record Holders: 1,977 The Vanguard Commission Banks (Lead Group, Inc. Subjects of Bank: Goldman Communication (7.06%) General Sachs, JPMorgan Equipment and Corporate Functions Product Content Professional The NASDAQ Business -

The Sharing Economy: Disrupting the Business and Legal Landscape

THE SHARING ECONOMY: DISRUPTING THE BUSINESS AND LEGAL LANDSCAPE Panel 402 NAPABA Annual Conference Saturday, November 5, 2016 9:15 a.m. 1. Program Description Tech companies are revolutionizing the economy by creating marketplaces that connect individuals who “share” their services with consumers who want those services. This “sharing economy” is changing the way Americans rent housing (Airbnb), commute (Lyft, Uber), and contract for personal services (Thumbtack, Taskrabbit). For every billion-dollar unicorn, there are hundreds more startups hoping to become the “next big thing,” and APAs play a prominent role in this tech boom. As sharing economy companies disrupt traditional businesses, however, they face increasing regulatory and litigation challenges. Should on-demand workers be classified as independent contractors or employees? Should older regulations (e.g., rental laws, taxi ordinances) be applied to new technologies? What consumer and privacy protections can users expect with individuals offering their own services? Join us for a lively panel discussion with in-house counsel and law firm attorneys from the tech sector. 2. Panelists Albert Giang Shareholder, Caldwell Leslie & Proctor, PC Albert Giang is a Shareholder at the litigation boutique Caldwell Leslie & Proctor. His practice focuses on technology companies and startups, from advising clients on cutting-edge regulatory issues to defending them in class actions and complex commercial disputes. He is the rare litigator with in-house counsel experience: he has served two secondments with the in-house legal department at Lyft, the groundbreaking peer-to-peer ridesharing company, where he advised on a broad range of regulatory, compliance, and litigation issues. Albert also specializes in appellate litigation, having represented clients in numerous cases in the United States Supreme Court, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, and California appellate courts. -

Hartnett Dissertation

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Recorded Objects: Time-Based Technologically Reproducible Art, 1954-1964 A Dissertation Presented by Gerald Hartnett to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University August 2017 Stony Brook University 2017 Copyright by Gerald Hartnett 2017 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Gerald Hartnett We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Andrew V. Uroskie – Dissertation Advisor Associate Professor, Department of Art Jacob Gaboury – Chairperson of Defense Assistant Professor, Department of Art Brooke Belisle – Third Reader Assistant Professor, Department of Art Noam M. Elcott, Outside Reader Associate Professor, Department of Art History, Columbia University This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Recorded Objects: Time-Based, Technologically Reproducible Art, 1954-1964 by Gerald Hartnett Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University 2017 Illuminating experimental, time-based, and technologically reproducible art objects produced between 1954 and 1964 to represent “the real,” this dissertation considers theories of mediation, ascertains vectors of influence between art and the cybernetic and computational sciences, and argues that the key practitioners responded to technological reproducibility in three ways. First of all, writers Guy Debord and William Burroughs reinvented appropriation art practice as a means of critiquing retrograde mass media entertainments and reportage. -

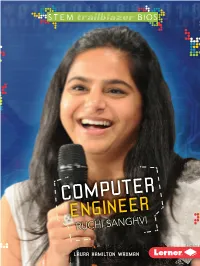

Computer Engineer Ruchi Sanghvi

STEM TRAILBLAZER BIOS COMPUTER ENGINEER RUCHI SANGHVI THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK INTENTIONALLY STEM TRAILBLAZER BIOS COMPUTER ENGINEER RUCHI SANGHVI LAURA HAMILTON WAXMAN Lerner Publications Minneapolis For Caleb, my computer wizard Copyright © 2015 by Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review. Lerner Publications Company A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. 241 First Avenue North Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com. Content Consultant: Robert D. Nowak, PhD, McFarland-Bascom Professor in Engineering, Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Wisconsin–Madison Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Waxman, Laura Hamilton. Computer engineer Ruchi Sanghvi / Laura Hamilton Waxman. pages cm. — (STEM trailblazer bios) Includes index. ISBN 978–1–4677–5794–2 (lib. bdg. : alk. paper) ISBN 978–1–4677–6283–0 (eBook) 1. Sanghvi, Ruchi, 1982–—Juvenile literature. 2. Computer engineers—United States— Biography—Juvenile literature. 3. Women computer engineers—United States—Biography— Juvenile literature. I. Title. QA76.2.S27W39 2015 621.39092—dc23 [B] 2014015878 Manufactured in the United States of America 1 – PC – 12/31/14 The images in this book are used with the permission of: picture alliance/Jan Haas/Newscom, p. 4; © Dinodia Photos/Alamy, p. 5; © Tadek Kurpaski/flickr.com (CC BY 2.0), p. -

US Mainstream Media Index May 2021.Pdf

Mainstream Media Top Investors/Donors/Owners Ownership Type Medium Reach # estimated monthly (ranked by audience size) for ranking purposes 1 Wikipedia Google was the biggest funder in 2020 Non Profit Digital Only In July 2020, there were 1,700,000,000 along with Wojcicki Foundation 5B visitors to Wikipedia. (YouTube) Foundation while the largest BBC reports, via donor to its endowment is Arcadia, a Wikipedia, that the site charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and had on average in 2020, Peter Baldwin. Other major donors 1.7 billion unique visitors include Google.org, Amazon, Musk every month. SimilarWeb Foundation, George Soros, Craig reports over 5B monthly Newmark, Facebook and the late Jim visits for April 2021. Pacha. Wikipedia spends $55M/year on salaries and programs with a total of $112M in expenses in 2020 while all content is user-generated (free). 2 FOX Rupert Murdoch has a controlling Publicly Traded TV/digital site 2.6M in Jan. 2021. 3.6 833,000,000 interest in News Corp. million households – Average weekday prime Rupert Murdoch Executive Chairman, time news audience in News Corp, son Lachlan K. Murdoch, Co- 2020. Website visits in Chairman, News Corp, Executive Dec. 2020: FOX 332M. Chairman & Chief Executive Officer, Fox Source: Adweek and Corporation, Executive Chairman, NOVA Press Gazette. However, Entertainment Group. Fox News is owned unique monthly views by the Fox Corporation, which is owned in are 113M in Dec. 2020. part by the Murdoch Family (39% share). It’s also important to point out that the same person with Fox News ownership, Rupert Murdoch, owns News Corp with the same 39% share, and News Corp owns the New York Post, HarperCollins, and the Wall Street Journal. -

Online Music Communities: Challenging Sexism, Capitalism, and Authority in Popular Music

ONLINE MUSIC COMMUNITIES ONLINE MUSIC COMMUNITIES: CHALLENGING SEXISM, CAPITALISM, AND AUTHORITY IN POPULAR MUSIC By PAUL ALEXANDER AITKEN, B.FA. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Paul Alexander Aitken, September 2007 MASTER OF ARTS (2007) McMaster University (Music Criticism) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Online Music Communities: Challenging Sexism, Capitalism, and Authority in Popular Music AUTHOR: Paul Alexander Aitken, B.FA. (York University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Christina Baade NUMBER OF PAGES: vii, 167 ii ABSTRACT With its almost exclusive focus on the economics of the music industry, the early-21 st century debate over digital music piracy has obscured other vital areas of study in the relationship between popular music and the Intemet. This thesis addresses some of these neglected areas, specifically issues of agency, representation, discipline, and authority; it examines each of these in relationship to the formation and maintenance different online music communities. I argue that contemporary online trends related to music promotion, consumption, and criticism are, in fact, part of a much larger socio-cultural re-envisioning of the relationships between artists and audiences, artists and the music industry, and among audience members themselves. The relationship between music and the Intemet is not only subversive on the level of economics. I examine these issues in three key areas. Independent women's music cOlmnunities challenge patriarchal authority in the music industry as they use online discussion forums and web sites to advance their own careers. The tension that exists between the traditional for-profit music industry and the developing ethic of sharing in the filesharing community creates the conditions whereby we can imagine aItemative ways that music can circulate in culture. -

New York Times: Free Speech Lawyering in the Age of Google and Twitter

THE “NEW” NEW YORK TIMES: FREE SPEECH LAWYERING IN THE AGE OF GOOGLE AND TWITTER Marvin Ammori INTRODUCTION When Ben Lee was at Columbia Law School in the 1990s, he spent three months as a summer associate at the law firm then known as Lord, Day & Lord, which had represented the New York Times1 in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan.2 During those months, Lee listened to the firm’s elder partners recount gripping tales of the Sullivan era and depict their role in the epic speech battles that shaped the future of free expression. Hearing these stories, a young Lee dreamed that one day he too would participate in the country’s leading speech battles and have a hand in writing the next chapter in freedom of expression. When I met with Lee in August 2013, forty-nine years after Sulli- van, he was working on freedom of expression as the top lawyer at Twitter. Twitter and other Internet platforms have been heralded for creating the “new media,”3 what Professor Yochai Benkler calls the “networked public sphere,”4 for enabling billions around the world to publish and read instantly, prompting a world where anyone — you and I included — can be the media simply by breaking, recounting, or spreading news and commentary.5 Today, freedom of the press means ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Fellow, New America Foundation; Partner, the Ammori Group. The Ammori Group is an “opinionated law firm” dedicated to advancing freedom of expression and Internet freedom, and its clients have included Google, Dropbox, Automattic, Twitter, and Tumblr. The author would like to thank Alvaro Bedoya, Yochai Benkler, Monika Bickert, Nick Bramble, Alan Davidson, Tony Falzone, Mike Godwin, Ramsey Homsany, Marjorie Heins, Adam Kern, Ben Lee, Andrew McLaughlin, Luke Pelican, Jason Schulman, Aaron Schur, Paul Sieminski, Ari Shahdadi, Laura Van Dyke, Bart Volkmer, Dave Willner, and Jonathan Zittrain. -

Global Flows in a Digital

McKinsey Global Institute McKinsey Global Institute Global flows in a digital trade, finance, How age: people, anddata connect worldthe economy April 2014 Global flows in a digital age: How trade, finance, people, and data connect the world economy The McKinsey Global Institute The McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, was established in 1990 to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. Our goal is to provide leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors with the facts and insights on which to base management and policy decisions. MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Our “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses on six themes: productivity and growth; natural resources; labor markets; the evolution of global financial markets; the economic impact of technology and innovation; and urbanization. Recent reports have assessed job creation, resource productivity, cities of the future, the economic impact of the Internet, and the future of manufacturing. MGI is led by three McKinsey & Company directors: Richard Dobbs, James Manyika, and Jonathan Woetzel. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, and Jaana Remes serve as MGI partners. Project teams are led by the MGI partners and a group of senior fellows, and include consultants from McKinsey & Company’s offices around the world. These teams draw on McKinsey & Company’s global network of partners and industry and management experts. -

Apple Inc. in 2010

9-710-467 REV: MARCH 21, 2011 DAVID B. YOFFIE R E N E E K I M Apple Inc. in 2010 On April 4, 2010, Apple Inc. launched its eagerly anticipated iPad amid great hype. The multimedia computer tablet was the third major innovation that Apple had released over the last decade. CEO Steve Jobs had argued that the iPad was another revolutionary product that could emulate the smashing success of the iPod and the iPhone. Expectations ran high. Even The Economist displayed the release of the iPad on its magazine cover with Jobs illustrated as a biblical figure, noting that, “The enthusiasm of the Apple faithful may be overdone, but Mr. Jobs’s record suggests that when he blesses a market, it takes off.”1 The company started off as “Apple Computer,” best known for its Macintosh personal computers (PCs) in the 1980’s and 1990’s. Despite a strong brand, rapid growth, and high profits in the late 1980s, Apple almost went bankrupt in 1996. Then Jobs went to work, transforming “Apple Computer” into “Apple Inc.” with innovative non-PC products starting in the early 2000’s. In fact, by 2010, the company viewed itself as a “mobile device company.”2 In the 2009 fiscal year, sales related to the iPhone and the iPod represented nearly 60% of Apple’s total sales of $43 billion.3 Even in the midst of a severe economic recession, revenues and net income both soared (see Exhibits 1a through 1c). Meanwhile, Apple’s stock was making history of its own. The share price had risen more than 15- fold since 2003 (See Exhibit 2).