Volume 42, Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of Kim

Ovid quate nulpa num entis mincto volup- taque labo. Itatum utem. Laboris ea nonse- quia demolupta dolumqui dolut alibus etusam Wong Maye-E AP A submarine-launched “Pukguksong” missile is displayed in Kim Il Sung Square in Pyongyang, REPUBLIC OF KIM ASSOCIATED PRESS STAFF STORY X 1 June 1, 2017 Wong Maye-E AP Missiles believed to be the Pukguksong 2 are displayed in Kim Il Sung Square in Pyongyang, North Korea. The Pukguksong 2 uses solid fuel, which means it can be hidden and ready for rapid launch. A new balance of terror: Why North Korea clings to its nukes By ERIC TALMADGE Associated Press PYONGYANG, North Korea (AP) — Early one winter morning, Kim Jong Un stood at a remote observation post overlooking a valley of rice paddies near the Chinese border. The North Korean leader beamed with delight as he watched four extended range Scud missiles roar of their mobile launchers, comparing the sight to a team of acrobats performing in unison. Minutes later the projectiles splashed into the sea of the Japanese coast, 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) from where https://apnews.com/f3cdf8f726084d13b33f09a5bd1845d0/A-new-balance-of-terror:-Why-North-Korea-clings-to-its-nukes Republic of Kim > ASSOCIATED PRESS p. 1 of 8 he was standing. It was an unprecedented event. North Korea had just run its frst simulated nuclear attack on an American military base. This scene from March 6, described in government propaganda, shows how the North’s seemingly crazy, suicidal nuclear program is neither crazy nor suicidal. Rather, this is North Korea’s very deliberate strategy to ensure the survival of its ruling regime. -

Multiple Myeloma Disrupts the TRANCE Osteoprotegerin

Multiple myeloma disrupts the TRANCE͞ osteoprotegerin cytokine axis to trigger bone destruction and promote tumor progression Roger N. Pearse*†, Emilia M. Sordillo‡, Shmuel Yaccoby§, Brian R. Wong¶, Deng F. Liau‡, Neville Colman‡, Joseph Michaeliʈ, Joshua Epstein§, and Yongwon Choi¶** Laboratories of *Molecular Genetics and ¶Immunology, and **Howard Hughes Medical Institute, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY 10021; ‡Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, St. Luke’s–Roosevelt Hospital Center, New York, NY 10025; §Myeloma Research Center, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR 72205; and ʈMyeloma Service, Department of Medicine, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, NY 10021 Communicated by Robert A. Good, University of South Florida, St. Petersburg, FL, July 27, 2001 (received for review January 9, 2001) Bone destruction, caused by aberrant production and activation of exhibit profound osteoporosis as a consequence of unopposed osteoclasts, is a prominent feature of multiple myeloma. We TRANCE activity (9). In addition, mice deficient in either demonstrate that myeloma stimulates osteoclastogenesis by trig- TRANCE or receptor activator of NF-B (RANK) exhibit gering a coordinated increase in the tumor necrosis factor-related defective lymph node organogenesis and early B cell develop- activation-induced cytokine (TRANCE) and decrease in its decoy ment (7, 10). However, the role of TRANCE and RANK in receptor, osteoprotegerin (OPG). Immunohistochemistry and in plasma cell differentiation and survival has not been evaluated. situ hybridization studies of bone marrow specimens indicate that We present evidence that MM disrupts the balance between in vivo, deregulation of the TRANCE–OPG cytokine axis occurs in TRANCE and its inhibitor, OPG. -

Dear Runners, One Big Happy CRC Family at Last Week's Slay the Dragon!

Issue no. 59 Sunday 4th March 2012 www.crewkernerc.btck.co.uk Dear Runners, One big happy CRC family at last week’s Slay The Dragon! Firstly may I remind you all that this coming Thursday is a pub run! We will run as usual from the car park at 6.30, with the option of a meal afterwards at Oscars for all who fancy it! If you are a newer member who hasn’t been to a pub run before, then why not make this your first?? Go on…. West Bay Run While I didn’t run myself today, I have hear from the wise Harwood that 7 ran from Crewkerne today, picking another 7 up at Wynyards Gap and 3 in Beaminster. While it was a wet and cold start the weather cleared by the time they had reached West Bay, where 11 stayed for food. Hope to bring some pictures next week! Slay The Dragon – The Results…. The results from last week’s 10k are in and we are also lucky the on site photographer got some cracking shots and has added his own little creative touch to them….at the expense of someone! Thanks Derek – kick a man while he’s down! Name Position Time Nick Sale 3rd 39.32 Tom Baker 6th 42.37 Simon Land 7th 42.48 Matt Bryant 8th 43.21 Rachel Hayton 31st 50.27 Roger Still 32nd 50.36 Linda Still 41st 52.49 Sarah Warren 42nd 52.54 Tim Hoyle 62nd 57.18 Sara Fair 77th 1.00.51 And finally…. -

Cape Town Marathon Men 2018 PROFILES

Cape Town Marathon Men 2018 PROFILES Nedbank Running Club - Administrative Head Office Tel: (012) 541 0577 Fax: (012) 541 3752 www.nedbankrunningclub.co.za CURRICULUM VITAE: Sintayehu Legese Yinesu PERSONAL INFORMATION SURNAME: Yinesu FIRST NAMES: Sintayehu COUNTRY: Ethiopia CLUB: Nedbank Running Club D.O.B: 1990 Personal Bests Event Result Venue Date Half Matrathon 1:02:59 Granollers (ESP) 01.02.2015 Marathon 2:11:07 Paris (FRA) 12.04.2015 Personal Performances 2018 Mandela Day Marathon (RSA) 2:28:02 (1st) Personal Performances 2017 Soweto Marathon (RSA) 2:20:56 (2nd) Personal Performances 2016 OR Thambo Marathon (RSA) 2:11:20 (2nd) Personal Performances 2015 Soweto Marathon (RSA) 2:23:20 (Winner) Granollers (ESP) 21km 1:02:59 Paris Marathon (FRA) 2:11:07 Personal Performances 2014 Soweto Marathon (RSA) 2:17:55 (Winner) Nedbank Running Club - Administrative Head Office Tel: (012) 541 0577 Fax: (012) 541 3752 www.nedbankrunningclub.co.za CURRICULUM VITAE: Ketema Bekele NEGASA PERSONAL INFORMATION SURNAME: Negasa FIRST NAMES: Ketema COUNTRY: Ethiopia CLUB: Nedbank Running Club D.O.B: 07.10.1986 Personal Bests Event Result Venue Date 42km 2:11:06 Cape Town Marathon (RSA) 2017 Personal Performances 2017 Cape Town Marathon (RSA) 2:11:06 Personal Performances 2016 Pyongyang Marathon (PRK) 2:14:31 Personal Performances 2014 Tiberias Marathon (ISR) 2:11:17 Gauteng Marathon (RSA) 2:15:05 (Winner) Personal Performances 2013 North Korea Marathon 2:12 (Winner) Siberian Marathon 2:13:23 (Winner) Pyongyang, PRK Mangyongdae Marathon 2:13:04 (Winner) -

Pyongyang Marathon Short Tour from Shanghai

Pyongyang Marathon Short Tour from Shanghai TOUR April 8th – 13th 2022 2.5 nights in North Korea + Shanghai-Pyongyang travel time OVERVIEW Visit North Korea from Shanghai for the Pyongyang Marathon, one of the most unique marathons in the world! This long weekend adventure packs in the main North Korea attractions with one of the liveliest events of the year. It may be quick, so brace yourself for an action- packed, comprehensive tour. We won't leave without visiting Pyongyang's highlights including; the Pyongyang Metro, one of the deepest subway systems in the world, the Mansudae Grand Monument, the massive bronze statues of the DPRK leadership in downtown, and the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, the country's museum to the Korean War and where you can climb aboard the captured US spy ship the USS Pueblo. This tour will even get you down to historic Kaseong, capital of the medieval Koryo Dynasty, for a tour of the DMZ featuring Panmunjom and the Joint Security Area. ➤ Pyongyang Marathon 2022 Koryo Tours are the official partners of the Pyongyang Marathon. The marathon is a World Athletics’ Bronze Label Road Race, and also has AIMS Certification. Join the race and receive the most unique finisher's medal, running shirt, and race certificates available. Even if you're not a serious runner, the Pyongyang Marathon is an event like no other. It starts and ends in Kim Il Sung Stadium - a stadium filled with over 50,000 North Koreans cheering you on as you finish your race. It's an experience like no other. -

ADMISSION EXAMINATION 2019/20 CHINESE PROGRAMMES 29 June 2019 19:00 – 21:00

Seat Number: Seat number: ADMISSION EXAMINATION 2019/20 CHINESE PROGRAMMES 29 June 2019 19:00 – 21:00 ENGLISH Time allowed: 2 hours Instructions: Follow instructions to every question carefully. Do not use a dictionary. Write ALL answers using a pen in this Examination Booklet. Applicant Number: AP19- ______________ Part A B C D E F Total Marks 26 10 10 14 20 20 100 Scores This Examination Booklet contains 11 pages including this one. Institute for Tourism Studies Chinese Programmes AP 19- ________________ Part A: Multiple Choice (26 marks) Choose the best answer to complete the following blanks. Circle the letter (a, b, or c) that represents the choice. 1. People _1_ have been to Hac Sa 8. The staff explained why the train was Beach before know its sand is black. delayed, but the passenger did not _8_ a. who the explanation. b. that a. accept c. which b. except c. aspect 2. The Senado Square is a _2_ tourists’ attraction. 9. Lately, there has been great debate _9_ a. popper many people on whether global warming b. popular is real. c. proper a. around b. among 3. My cousin and I have not talked to c. amount _3_ for more than 5 years. 10. _10_ seems to notice the newly opened a. each another café. It needs more promotion. b. each other a. Anybody c. each one other b. Nobody 4. _4_ the police arrived, the suspect c. Somebody had already left. 11. I know you can eat that extremely hot a. After chili, but I think you _11_. -

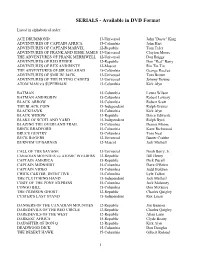

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format Listed in alphabetical order: ACE DRUMMOND 13-Universal John "Dusty" King ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN AFRICA 15-Columbia John Hart ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL 12-Republic Tom Tyler ADVENTURES OF FRANK AND JESSE JAMES 13-Universal Clayton Moore THE ADVENTURES OF FRANK MERRIWELL 12-Universal Don Briggs ADVENTURES OF RED RYDER 12-Republic Don "Red" Barry ADVENTURES OF REX AND RINTY 12-Mascot Rin Tin Tin THE ADVENTURES OF SIR GALAHAD 15-Columbia George Reeves ADVENTURES OF SMILIN' JACK 13-Universal Tom Brown ADVENTURES OF THE FLYING CADETS 13-Universal Johnny Downs ATOM MAN v/s SUPERMAN 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BATMAN 15-Columbia Lewis Wilson BATMAN AND ROBIN 15-Columbia Robert Lowery BLACK ARROW 15-Columbia Robert Scott THE BLACK COIN 15-Independent Ralph Graves BLACKHAWK 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BLACK WIDOW 13-Republic Bruce Edwards BLAKE OF SCOTLAND YARD 15-Independent Ralph Byrd BLAZING THE OVERLAND TRAIL 15-Columbia Dennis Moore BRICK BRADFORD 15-Columbia Kane Richmond BRUCE GENTRY 15-Columbia Tom Neal BUCK ROGERS 12-Universal Buster Crabbe BURN'EM UP BARNES 12-Mascot Jack Mulhall CALL OF THE SAVAGE 13-Universal Noah Berry, Jr. CANADIAN MOUNTIES v/s ATOMIC INVADERS 12-Republic Bill Henry CAPTAIN AMERICA 15-Republic Dick Pucell CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT 15-Columbia Dave O'Brien CAPTAIN VIDEO 15-Columbia Judd Holdren CHICK CARTER, DETECTIVE 15-Columbia Lyle Talbot THE CLUTCHING HAND 15-Independent Jack Mulhall CODY OF THE PONY EXPRESS 15-Columbia Jock Mahoney CONGO BILL 15-Columbia Don McGuire THE CRIMSON GHOST 12-Republic -

Title of Thesis Or Dissertation, Worded

COWBOY UP: EVOLUTION OF THE FRONTIER HERO IN AMERICAN THEATER, 1872 – 1903 by KATO M. T. BUSS A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Theater Arts and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2012 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Kato M. T. Buss Title: Cowboy Up: Evolution of the Frontier Hero in American Theater, 1872 – 1903 This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Theater Arts by: Dr. John Schmor Co-Chair Dr. Jennifer Schlueter Co-Chair Dr. John Watson Member Dr. Linda Fuller Outside Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded March 2012 ii © 2012 Kato M. T. Buss iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Kato M. T. Buss Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theater Arts March 2012 Title: Cowboy Up: Evolution of the Frontier Hero in American Theater, 1872 – 1903 On the border between Beadle & Adam’s dime novel and Edwin Porter’s ground- breaking film, The Great Train Robbery, this dissertation returns to a period in American theater history when the legendary cowboy came to life. On the stage of late nineteenth century frontier melodrama, three actors blazed a trail for the cowboy to pass from man to myth. Frank Mayo’s Davy Crockett, William Cody’s Buffalo Bill, and James Wallick’s Jesse James represent a theatrical bloodline in the genealogy of frontier heroes. -

Women's 100 Metres

IAAF World Championships Doha 2019 • Biographical Entry List • Women Women’s 100 Metres 52 Entrants Starts: Saturday, Sep 28 (16:30) 2019 World Best: 10.73 Elaine Thompson JAM Kingston 21 Jun 19 10.73 Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce JAM Kingston 21 Jun 19 Championship Record: 10.70 Marion Jones USA Seville 22 Aug 99 = IAAF invitee Age (Days) Born SB PB 225 GAITHER Tynia BAH 26y 194d 1993 11.04 11.04 -19 (Tynia pronounced ‘Tye-nia Gay-thurr’) Performed above expectations to reach the World 200m final in 2017 200 pb: 22.54 -16 (22.69 -19). 2 Youth Olympic Games 200 2010; sf WJC 200 2010; sf OLY 200 2016 (ht 100); 8 WCH 200 2017. 1 Bahamian 100/200 2016 (1 100 2017). Student of sociology at the University of Southern California In 2019: 1 Houston 400; 1 San Marcos 100/20; 1 St. Georges 200; 1 Houston 100; 2 Baie-Mahault 200; 3 Kingston Racers invitational 200; 4 Boston Games 150; 1 Houston 100; 1 Montverde 100; 1 Lucerne 200 (5 100); 2 Bahamian 100; 3 Pan-Am Games 200; 4 Madrid 100; 4 Rovereto 100; 1ht Bellinzona 100; 3 Zagreb 200; 1 Andújar 200 341 SANTOS Rosângela BRA 28y 280d 1990 11.23 10.91 -17 AR South American record holder at 60m & 100m. 2008 Olympic relay bronze (awarded in 2016!) 200 pb: 22.77 -15. 1 South American junior 100 2007; 4 World Youth 200 2007; 3 WJC 4x100 2008 (4 100); 3 OLY 4x100 2008; 5 WSG 100 2011; sf WCH 100 2011; 1 Pan-Am Games 100 2011 (2015-4); 1 Ibero-American 100 2012/2016; sf OLY 100 2012/2016; sf WCH 100/200 2015; sf WIC 60 2016; 7 WCH 100 2017; ht WIC 60 2018; 1 Pan-Am Games 4x100 2019. -

Facts Versus Fears

FACTS VERSUS FEARS: A REVIEW OF THE GREATEST UNFOUNDED HEALTH SCARES OF RECENT TIMES by ADAM J. LIEBERMAN (1967–1997) SIMONA C. KWON, M.P.H. Prepared for the American Council on Science and Health THIRD EDITION First published May 1997; revised September 1997; revised June 1998 ACSH accepts unrestricted grants on the condition that it is solely responsible for the conduct of its research and the dissemina- tion of its work to the public. The organization does not perform proprietary research, nor does it accept support from individual corporations for specific research projects. All contributions to ACSH—a publicly funded organization under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code—are tax deductible. AMERICAN COUNCIL ON SCIENCE AND HEALTH 1995 Broadway, 2nd Floor New York, NY 10023-5860 Tel. (212) 362-7044 • Fax (212) 362-4919 URL: http://www.acsh.org • E-mail: [email protected] Individual copies of this report are available at a cost of $5.00. Reduced prices for 10 or more copies are available upon request. June 1998-03000. Entire contents © American Council on Science and Health, Inc. THE AMERICAN COUNCIL ON SCIENCE AND HEALTH GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES THE COMMENTS AND CONTRIBUTIONS OF THE FOLLOWING INDIVIDUALS. Dennis T. Avery, M.A. Gordon W. Gribble, Ph.D. James E. Oldfield, Ph.D. Center for Global Food Issues Dartmouth College Oregon State University Hudson Institute Rudolph J. Jaeger, Ph.D. M. Alice Ottoboni, Ph.D. Thomas G. Baumgartner, Pharm.D., Environmental Medicine, Inc. Sparks, Nevada M.Ed., FASHP, BCNSP University of Florida Edward S. Josephson, Ph.D. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Weeklies Box Folder Folder Name

Shirley Papers 439 General Reference, Published Materials, Weeklies Box Folder Folder Name General Reference Published Materials Weeklies All Around Weekly, New York: Frank Tousey, 1909-1911 877 1 Shackleford, H. K. Deserted in Dismal Swamp; or, The secrets of the lone hut. no. 41. August 4, 1910. RC2006.068.4.01087 2 Turner, Frank R. The golden skull; or, A boy's adventures in Australia. no. 45. Sept. 2, 1910. RC2006.068.4.01088 3 Ellison, Dick The hand of fate; or, The hawks of New York. no. 51. Oct. 14, 1910. RC2006.068.4.01089 4 Shackleford, H. K. Black Hills Bill; or, The gold of Canyon Gulch. no. 57. Nov. 25, 1910. RC2006.068.4.01090 5 “Pawnee Jack” Hank Monk; or, The stage driver of the Pacific slope. no. 61. Dec. 23, 1910. RC2006.068.4.01091 6 Ellison, Dick The crimson cowl; or, The bandit of San Basilio. no. 64. Jan. 13, 1911. RC2006.068.4.01092 7 Rogers, Geo. W. Hunting the wolf-killers; or, Perils in the Northwest. no. 66. Jan. 27, 1911. RC2006.068.4.01093 All-Sports Library, New York: The Winner Library Co 8 Stevens, Maurice Jack Lightfoot's winning oar; or, A hot race for the cup. no. 8. April 1, 1905. RC2006.068.4.01138 9 Stevens, Maurice Jack Lightfoot's first victory; or, A battle for blood. no. 54. Feb. 17, 1906. RC2006.068.4.01139 American Indian Weekly, Cleveland, OH: Arthur Westbrook Co., 1910- 1911 10 Dair, Spencer Tracked to his lair; or, The pursuit of the Midnight Raider.