Post Magazine April 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urs Fischer – False Friends MUSÉE D’ART ET D’HISTOIRE, GENEVA

Urs Fischer – False Friends MUSÉE D’ART ET D’HISTOIRE, GENEVA APRIL 28 – JULY 17, 2016 PRESS RELEASE A selection of the Dakis Joannou Collection in Geneva for the first time March 2016 - Beginning on April 28, 2016, the Museum of Art and History of Geneva welcomes the DESTE Foundation, introducing the exhibition Urs Fischer – False Friends, in collaboration with of ART for The World. Urs Fischer – False Friends brings together a selection of works from the Dakis Joannou Collection. Conceived as an unusual synthesis between a solo show and a group exhibition, False Friends pairs works by a range of highly recognized artists with an ensemble of 20 works by Swiss artist Urs Fischer (b. 1973). In False Friends, Urs Fischer's work is seen alongside sculptures and paintings by artists such as Pawel Althamer, Maurizio Cattelan, Fischli and Weiss, Robert Gober, Martin Kippenberger, Jeff Koons, Paul McCarthy, Cindy Sherman and Kiki Smith, all of whom engage with fundamental themes in the history of art – the representation of the human body, the transformative power of materials, and the virtues of subtle observations. Establishing unexpected connections between artworks and aesthetics, methods and materials, False Friends traces similarities and differences among a group of artists whose work has animated and sustained critical debates in contemporary art throughout the past thirty years. The work of Urs Fischer, one of the most innovative Swiss artists of his generation, is central to False Friends. Fischer celebrates metamorphosis and change through works that reveal a particular attention to process and time. Coupling the legacy of Pop art with a neo-baroque taste for the absurd, Fischer’s creative universe trembles under the forces of entropy, decay and failure. -

Artdesk Is a Free Quarterly Magazine Published by Kirkpatrick Foundation

TOM SHANNON / ANDY WARHOL / AYODELE CASEL / WASHI NGTON D.C. / AT WORK: TWYLA THARP / FALL 2019 CONTEMPORARY ARTS, PERFORMANCE, AND THOUGHT ON I LYNN THOMA ART FOUNDAT ART THOMA LYNN I ROBERT IRWIN, Lucky You (2011) One of the many artworks in Bright Golden Haze (opening March 2020) at the new Oklahoma Contemporary Arts Center ArtDesk is a free quarterly magazine published by Kirkpatrick Foundation. COLLECTION OF THE CARL & MAR & CARL THE OF COLLECTION LETTING GO | Denise Duong The Pink Lady | I N A COCKTAI L SHAKER FULL OF I CE, SHAKE ONE AND A HALF OUNCES OF LONDON DRY GI N , A HALF OUNCE OF APPLEJACK, THE JUI CE OF HALF A LEMON, ONE FRESH EGG WHI TE, AND TWO DASHES OF GRENADI NE. POUR I NTO A COCKTAI L GLASS, and add a cherry on top. FALL ART + SCI ENCE BY RYAN STEADMAN GENERALLY, TOM SHANNON sees “invention” and “art” as entirely separate. Unlike many contemporary artists, who look skeptically at the divide between utility and fine art, Shannon embraces their opposition. “To the degree that something is functional, it is less ‘art.’ Because art is a mysterious activity,” he says. “I really distinguish between the two activities. But I can’t help myself as far as inventing, because I want to improve things.” TOM SHANNON Pi Phi Parallel (2012) ARTDESK 01 TOM SHANNON Parallel Universe (2012) (2009) SHANNON’S CAREER WAS launched at a young age, telephone, despite being ground-breaking for the after a sculpture he made at nineteen was included 1970s, was never fabricated on any scale. -

G a G O S I a N Urs Fischer Bibliography

G A G O S I A N Urs Fischer Bibliography Books and Catalogues: 2017 Fischer, Urs. Phantom Paintings. New York: Kiito-San. Pissarro, Joachim. Urs Fischer: Bruno & Yoyo. New York: Kitto-San and Vito Schnabel Gallery. 2016 Fischer, Urs. YES. New York: DESTE Foundation, Kiito-San. Fischer, Urs and Curiger, Brice. Mon cher... Arles: Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles. 2013 Curiger, Bice. Barroco exuberante: De Cattelan a Zurbarán—Manifiestos de la precariedad vital. Bilbao: Museo Guggenheim Bilbao. de Seta, Cesare. Biennali souvenir. Milan: Mondadori Electa: 112–5. Fischer, Urs. The Making of Yes. New York: Kiito-San. Morgan, Jessica, Ulrich Lehmann and Jeffrey Deitch. Urs Fischer. New York: Kiito- San. Fischer, Urs, Jessica Morgan, and Karen Marta. Urs Fischer: 2000 words. Friedman, Samantha. Van Gogh, Dalí, and Beyond: The World Reimagined. New York: The Museum of Modern Art; Perth, Art Gallery of Western Australia: 95. Gnyp, Marta. Made in Mind: Myths and Realities of the Contemporary Artist. Stockholm: Art and Theory: 95–101. Holzwarth, Hans Werner. Art Now, Volume 4.Cologne: Taschen: 134–7. Lehmann-Reupert, Susanne. Von New York lernen: Mit Stuhl, Tisch und Sonnenschirm. Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz. 2012 Blancsubé, Michel. Poule! Ecatepec, Mexico: Fundación/Colección Jumex. Chaillou, Timothée. Seuls quelques fragments de nous toucheront quelques fragments d’autrui (Only parts of us will ever touch parts of others). Paris/Salzburg: Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac. Curiger, Bice. Deftig Barock. Von Cattelan bis Zurbarán—Manifeste des prekär Vitalen. Zurich: Kunsthaus Zürich. Deitch, Jeffrey. The Painting Factory: Abstraction after Warhol. New York: Skira Rizzoli. Driessen, Chris, and Heidi van Mierlo, eds. -

«Fastes Et Grandeur Des Cours En Europe »

PRESS KIT SOMMAIRE THE EXHIBITION: - PRESENTATION OF ARTLOVERS 3 Stories of Art in the Pinault Collection -THE EXHIBITION ITINERARY 4 -THE LIST OF WORKS 9 -BIOGRAPHIES OF THE ARTISTS 15 -THE CURATOR MARTIN BETHENOD 23 -THE SCENOGRAPHER FREDERIC CASANOVA 26 -THE LIST OF IMAGES AVAILABLE TO THE PRESS 29 PRESENTATION OF THE PINAULT COLLECTION: -THE PINAULT COLLECTION 34 -THE COLLECTOR 35 -THE PLACES AND THE EXHIBITIONS IN 2014 36 THE GRIMALDI FORUM -PRESENTATION 37 -PRACTICAL INFORMATION 39 THE PARTNERS -CMB 41 -D’AMICO 43 -FRANCE INTER 44 2 THE EXHIBITION – PRESENTATION OF ARTLOVERS Stories of art in the Pinault Collection ARTLOVERS, a selection of forty major art works from the Pinault collection—works especially chosen to illustrate the links and relationship, visible or secret, with anterior works—will be shown at the Grimaldi Forum Monaco beginning on July 12, 2014. The idea of the intertextuality of art “in the second degree” will thus be the recurrent theme in the choice of works presented at Monaco, bringing together some of the most famous pieces of art of the collection along with rarer works, including fifteen never before shown in earlier exhibitions. Through quotations, allusions, references, parodies, praise, criticism, diversion, remakes, appropriation, reuse etc, “ARTLOVERS” will explore the extraordinary dynamics of inspiration, of transformation, of the production of forms and ideas emerging from the diversity of the intertwining relationships between the art works. A positive dynamic, owning nothing to backward-looking -

Urs Fischer 30 YEARS of PARKETT 30 YEARS of PARKETT

Urs Fischer 30 YEARS OF PARKETT 30 YEARS OF PARKETT URS FISCHER’S OBJECTS AND IMAGES NICHOLAS CULLINAN KLEINES PROBLEM, Aluminiumpaneel, Aluminium- Aluminiumpaneel, PROBLEM, KLEINES V 4 " / When I visit Urs Fischer’s studio in Red Fischer’s wax sculptures: larger-than-life >D Hook, Brooklyn, one morning in March, the scans of the artist himself and friends and fel place is abuzz with activity. I say “studio,” but low artists such as Rudolf Stingel and, on this that seems an outmoded and insufficient particular day, Adam McEwen. These are first term with which to describe the sheer array rendered in urethane foam and will eventu of works and panoply of projects under way. ally be cast as giant candles left to burn and Dispersed around the cavernous space of a melt slowly over the course of many days and former hosiery distribution company are weeks, eventually extinguishing-—master several recent works from his ongoing series classes in entropy like Fischer’s memorable of “PROBLEM PAINTINGS”—vast aluminum waxen copy of Giambologna’s RAPE OF THE panels printed with vintage black-and-white SABINE WOMEN at the 2011 Venice Biennale. photographs of Hollywood stars from the But on the afternoon I stop by, among the golden era like Paul Newman, which Fischer team of people working on various produc has colored digitally. Their famous features tions in separate zones devoted to photogra are foregrounded and half-obscured by in phy, screen-printing, and archives, the most congruous objects such as a half-burned cig pressing deadline and urgent task seems to arette, a squashed banana, or a bent screw. -

Urs Fischer Born in Zurich, Switzerland. Lives and Works In

Urs Fischer Born in Zurich, Switzerland. Lives and works in Berlin, Los Angeles and Zurich Studied Photography at the Schule für Gestaltung, Zurich Visited ʻde ateliersʼ, Amsterdam Artist in Residence, Delfina Studios, London Solo Exhibitions 2011 54th International Art Exhibition Biennale, Venice 2010 Sadie Coles HQ, London Oscar the Grouch, Brant Foundation, Greenwich (CT), USA 2009 Marguerite de Ponty, New Museum, New York “Dear _________! We _____ on ________, hysterically. It has to be _____ that _____. No? It is now ______ and the whole _______ has changed ______. all the _____, ______”, Kunstnernes Hus, OsloMarguerite de Ponty, New Museum, New York (NY), USA Conflicting Tales: Subjectivity (Quadrilogy, Part 1), Burger Collection, Berlin, Germany 2008 Blurry Renoir Debussy, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zürich, Switzerland "Who's Afraid of Jasper Johns?" A show conceived by Urs Fischer & Gavin Brown, Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York (NY), USA 2007 Large, dark & empty, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zürich Agnes Martin, Regen Projects II, Los Angeles You, Gavin Brownʼs Enterprise, NewYork Uh…. Sadie Coles HQ, London 52nd International Art Exhibition Biennale, Venice (with Ugo Rondinone) Cockatoo Island, Kaldor Art Projects and the Sydney Federation Trust, Sydney 2006 The Modern Institute, Glasgow, Scotland Gallerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich Mary Poppins, Blaffer Gallery, University of Houston, Houston (TX) Paris 1919, Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam Galerie Massimo de Carlo, Milan 2005 Hamburger Bahnhof, Flick Collection, Berlin “Mr Watson -

Urs Fischer Biography

Sadie Coles HQ Urs Fischer Biography 1973 Born in Zurich, Switzerland Lives and works in New York (NY) and Zurich, Switzerland Studied Photography at the Schule für Gestaltung, Zurich, Switzerland Visited ‘de ateliers’, Amsterdam Artist in Residence, Delfina Studios, London Solo Exhibitions 2020 Aïshti Foundation, Beirut 2019 Leo, Gagosian, Paris ERROR, The Brant Foundation, Greenwich (CT), USA PLAY, Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles (CA), USA Sirens, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin Images, Gagosian, Los Angeles (CA), USA 2018 Dasha, Gagosian, London Urs Fischer & Rudolf Stingel, Paul Coulon Gallery, London PLAY, Gagosian, New York (NY) soft, Sadie Coles HQ, London Things, Gagosian, New York (NY) Sōtatsu, Gagosian, New York (NY) Maybe, The Modern Institute, Glasgow, Scotland, UK 2017 Bus Stop (permanent installation), Paradise Plaza, Miami (FL), USA Bliss, Urs Fischer x Katy Perry, 39 Spring Street, New York (NY) " ", Gavin Brown’s enterprise, Sant'Andrea de Scaphis, Rome Big Clay #4 and Two Tuscan Men, Piazza della Signoria, Florence, Italy Faules Fundament (Rotten Foundation)!, Karma, New York (NY) The Public & the Private, Legion of Honor, San Francisco (CA), USA [Music note title], Gagosian, Hong Kong The Kiss, Sadie Coles HQ, London You, Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York (NY) 2016 Mind Moves, Gagosian, San Francisco (CA), USA Mon Cher…, Fondation Vincent van Gogh, Arles, France Battito Di Ciglia, Massimo De Carlo, Milan, Italy Untitled (Lamp/Bear), Simmons Quad, Brown University, Providence (RI), USA Small Axe, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow Ursula, JTT, New York (NY) Misunderstandings in the Quest for the Universal, Gagosian, New York (NY) 2015 Bruno & Yoyo, Vito Schnabel Gallery – St. -

Download Full Bibliography

Sadie Coles HQ Urs Fischer Selected Bibliography Monographs and Solo Exhibition Catalogues 2020 Gregor Jansen, Fischer: Sirens (Berlin: Holzwarth Publications, 2020) 2019 Urs Fsicher and Spencer Sweeney, HEADZ (Los Angeles: Kiito-San, 2019) Priya Bhatnagar, Jamie Gecker, Abby Haywood, Angela Kunicky, Annie Roft and Natalie Skinner, Urs Fischer: Paintings 1998 – 2017 (Los Angeles: Kiito-San, 2019) Urs Fischer, Band-AIDS (Los Angeles: Kiito-San, 2019) Priya Bhatnagar, Urs Fischer: Sculptures 2013-2018 (Los Angeles: Kiito-San, 2019) 2017 Urs Fischer, Dominique Clausen, Phantom Paintings (Switzerland: Kiito-San, 2017) Joachim Pissarro, Bruno & Yoyo (Kiito-San / Switzerland: Vito Schnabel Gallery, 2017) 2016 Urs Fischer, Yes (Athens: DESTE Foundation; Los Angeles: Kiito-San, 2016) 2013 Urs Fischer (ed.) The Making of Yes (New York: Kiito-San, 2013) Jeffrey Deitch, Jessica Morgan, Ulrich Lehmann, Urs Fischer: Museum of Contemporary Art (New York: Kiito-San, 2013) Massimiliano Gioni (ed.) 2000 Words (Athens: DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art, 2013) 2012 Adam McEwan, Urs Fischer: Beds & Problem Paintings (California: Gagosian Gallery, 2012) Caroline Bourgeois (ed.) Madame Fisscher (New York: Kiito-San, 2012) Oscar the Grouch (Greenwich (CT): The Brant Foundation; New York: Kiito-San, 2012) Gerald Matt (ed.) Urs Fischer: Skinny Sunrise (New York: Kiito-San, 2012) Urs Fsicher and Georg Herold. Necrophonia (New York: Kiito-San, 2012) 2011 Urs Fischer (ed.), dngszjkdufiy bgxfjkglijkhtr kydjkhgdghjkd (Self-published artist book in three parts) -

FA05 Layout 001-032 V4 Copy.Qxd 6/7/12 12:16 PM Page 1

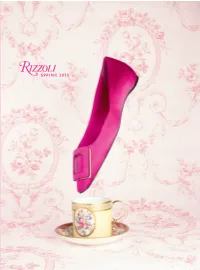

3 1 0 2 G N I R P S RIZZOLI SPRING 2013 SP13 Front cover REDUCED SIZE_Layout 1 6/6/12 10:54 AM Page 1 SP13 cover INSIDE LEFT_FULL SIZE_Layout 1 6/6/12 11:05 AM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS RIZZOLI Altagamma . .46 Urs Fischer . .48 Aragones . .34 Vegetarian Everyday . .20 The Boudoir Bible . .4 Watches International . .51 The Bronfman Haggadah . .44 The Welcoming House . .9 Coconut Grove . .16 Costa Smeralda . .47 UNIVERSE CZ Guest . .7 1,001 Golf Holes You Must Play Before You Die . .54 Designers at Home: Personal Reflections on Stylish Living . .15 The Adventurer's Guide to the Outdoors . .52 The Diary of a Nose . .14 All the Buildings in New York . .59 Dior . .5 The Best Things to Do in Los Angeles . .60 Dolce&Gabbana Campioni . .42 Davis Cup . .28 Elegant Rooms that Work . .21 Horse Sanctuary . .57 Exit Strategy . .45 Isms…Understanding Modern Art . .54 Francesco Vezzoli . .24 Paris, Line by Line . .58 Fuct . .26 Popcorn! . .61 A Golden Age: ?Surfing’s Revolutionary 1960s and ’70s . .29 The Racing Bicycle . .56 Grand Complications . .51 Spectacular Scotland . .60 Greenwich Style . .18 Stuck on Star Trek . .53 Happy Home . .19 Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse Tales . .55 Heirloom Modern . .8 Henry Moore . .49 BACK IN PRINT Houses with Charm: Simple Southern Style . .37 Cottages on the Coast . .51 How to Read Fashion . .22 Frederick Law Olmsted . .51 The International Tennis Federation . .28 Jean-Michel Frank . .51 It All Dies Anyway . .27 Legendary Golf Clubhouses of Great Britain and the U.S. .10 SKIRA RIZZOLI Luxurious Minimalism . -

(SELF) Portraits & Self-Portraits PORTRAITS Made by Artists for Parkett Since 1984

(self) por traits MADE BY ARTISTS FOR PARKETT SINCE 1984 PARKETT SPACE ZURICH Feb 22– Jul 18, 2020 53 (SELF) Portraits & Self-Portraits PORTRAITS Made by Artists for Parkett since 1984 Pawel´ Althamer, 82 Katharina Fritsch, 100/101 Lucy McKenzie, 76 Dayanita Singh, 95 Laurie Anderson, 49 Ellen Gallagher, 73 Marilyn Minter, 79, 100/101 Frances Stark, 93 Ed Atkins, 98 Adrian Ghenie, 99 Tracey Moffatt, 53 Rudolf Stingel, 77 John Baldessari, 29, 86 Gilbert & George, 14 Mariko Mori, 54 Beat Streuli, 54 Stephan Balkenhol, 36 Robert Gober, 27 Juan Muñoz, 43 Wolfgang Tillmans, 53 Georg Baselitz, 11 Douglas Gordon, 49 Bruce Nauman, 10 Rirkrit Tiravanija, 44 Alighiero e Boetti, 24 Dan Graham, 68 Olaf Nicolai, 78 Fred Tomaselli, 67 Christian Boltanski, 22 Rodney Graham, 64 Albert Oehlen, 79 Rosemarie Trockel, 33, 95 Kerstin Brätsch and Mark Grotjahn, 80 Paulina Olowska, 92 Luc Tuymans, 60 DAS INSTITUT, 88 Rachel Harrison, 82 Tony Oursler, 47 Charline von Heyl, 89 Glenn Brown, 75 Camille Henrot, 97 Nicolas Party, 100/101 Kara Walker, 59 Sophie Calle, 36 Jenny Holzer, 40/41 Mai-Thu Perret, 84 Kelley Walker, 87 Maurizio Cattelan, 59, 100 Gary Hume, 48 Elizabeth Peyton, 53 Jeff Wall, 22 Chuck Close, 60 Christian Jankowski, 81 Richard Phillips, 71 Andy Warhol, 12 John Currin, 65 Alex Katz, 21, 72 Sigmar Polke, 40/41 John Waters, 96 Martin Disler, 3 Mike Kelley, 31 Richard Prince, 72 Gillian Wearing, 70 Nathalie Djurberg, 90 Jon Kessler, 79 R.H. Quaytman, 90 Lawrence Weiner, 42 Peter Doig, 67 Karen Kilimnik, 52 Markus Raetz, 8 Andro Wekua, 88 Marlene Dumas, -

Urs Fischer: Marguerite October 28, 2009–February 7, 2010 De Ponty Second, Third and Fourth Floors

URS FISCHER: MARGUERITE OCTOBER 28, 2009–FEBRUARY 7, 2010 DE PONTY SECOND, THIRD AND FOURTH FLOORS Urs Fischer creates artworks that give physical form Using an intricate mapping system, the photographs to fantasy. Encompassing the wonder of the sublime, were tiled together to create wallpaper. Instead of gestures of brute force, and interventions that the wall, the viewer sees the corresponding image of subtly alter the viewer’s perception, Fischer’s work the shadowed wall, turning the area that is usually is captivating whether it is immediately impressive intended to recede from the eye into the work of or mischievously unnoticeable. Like a practiced art itself, an incongruity that makes the piece both magician, Fischer succeeds in transforming materials alluring and illogical. into unpredictable inventions, fusing slapstick humor with explorations of scale and distortion. While his By comparison, the second floor is a spectacle oeuvre does not reveal a recognizable stylistic unity, of images. Arguably Fischer’s most ambitious imagination plays a central role in all of his work. installation to date, this project consisted of an inventory of fifty-one objects selected by the artist, Fischer was born in Zurich in 1973 and currently lives approximately 25,000 photographs, and more and works in New York. This exhibition marks his than twelve tons of steel. Fischer had each object first large-scale solo show in an American museum, photographed from every side in great detail, and as well as the first time one artist has installed all then silkscreened the images onto fifty mirrored three of the New Museum’s gallery floors. -

Biography Urs Fischer

Biography Urs Fischer Zurich, Switzerland, 1973. Lives and works in New York SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 2019 - Images, Gagosian, Beverly Hills, USA 2019 - Sirens, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, D 2019 - Te Lyrical and Te Prosaic, Aishti Foundation, Beirut, RL 2018 2018 - Tings, Gagosian, New York, USA 2018 - SŌTATSU, Gagosian, New York, USA 2018 - Maybe, Te Modern Institute, Glasgow, UK 2018 - Dasha, Gagosian, London, UK 2018 - Play, Gagosian, New York, USA 2017 2017 - Urs Fischer: Te Public & the Private, Te Legion of Honor, San Francisco, USA 2017 - Urs Fischer , Gagosian, Hong Kong, HK 2017 - Te Kiss, Sadie Coles HQ, London, UK 2017 - In Florence, Piazza Signoria, Firenze, I 2017 - Bus Stop, Permanent installation, Paradise Plaza, Miami, USA 2017 - Urs Fischer x Katy Perry: Bliss, 39 Spring Street, New York, USA 2017 - " ", Gavin Brown's enterprise, Rome, I 2017 - Faules Fundament (Rotten Foundation)!, Karma, New York, I 2017 - you, Gavin Brown's enterprise, New York, USA 2016 2016 - Small Axe, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow, RUS 2016 - Ursula, JTT, New York, USA 2016 - Misunderstandings in the Quest for the Universal, Gagosian Gallery, 980 Madison Avenue, New York, USA 2016 - Battito di Ciglia, Massimo De Carlo, Milano, I 2016 - "Mon Cher ...", Fondation Vincent Van Gogh, Arles, F. Catalogue 2016 - Mind Moves, Gagosian Gallery, San Francisco, USA 2016 - Untitled (Lamp/Bear), Simmons Quad, Brown University, Providence, USA 2015 2015 - Bruno & Yoyo, Vito Schnabel Gallery, St. Moritz, CH. Catalogue 2015 - Fountains, Gagosian Gallery,