The Auslink White Paper: an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’S Guide

New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’s Guide Important: This Operator’s Guide is for three Notices separated by Part A, Part B and Part C. Please read sections carefully as separate conditions may apply. For enquiries about roads and restrictions listed in this document please contact Transport for NSW Road Access unit: [email protected] 27 October 2020 New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’s Guide Contents Purpose ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 NSW Travel Zones .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Part A – NSW Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicles Notice ................................................................................................ 9 About the Notice ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 1: Travel Conditions ................................................................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Pilot and Escort Requirements .......................................................................................................................... -

NORTH WEST Freight Transport Strategy

NORTH WEST Freight Transport Strategy Department of Infrastructure NORTH WEST FREIGHT TRANSPORT STRATEGY Final Report May 2002 This report has been prepared by the Department of Infrastructure, VicRoads, Mildura Rural City Council, Swan Hill Rural City Council and the North West Municipalities Association to guide planning and development of the freight transport network in the north-west of Victoria. The State Government acknowledges the participation and support of the Councils of the north-west in preparing the strategy and the many stakeholders and individuals who contributed comments and ideas. Department of Infrastructure Strategic Planning Division Level 23, 80 Collins St Melbourne VIC 3000 www.doi.vic.gov.au Final Report North West Freight Transport Strategy Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... i 1. Strategy Outline. ...........................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background .............................................................................................................................1 1.2 Strategy Outcomes.................................................................................................................1 1.3 Planning Horizon.....................................................................................................................1 1.4 Other Investigations ................................................................................................................1 -

Barton Highway FAQ December 2020

Barton Highway FAQ December 2020 Questions Answers Where is the Barton The Barton Highway is about 52 kilometres in length, connecting the Hume Highway near Yass and the Highway located? surrounding rural and residential areas to the ACT. The highway plays a strategically significant role at a national and local level. It forms one part of the Sydney-Canberra-Melbourne road corridor, allowing freight movements between the three cities. On a local level, the highway connects the townships of Yass and Murrumbateman in NSW and Hall in the ACT; and surrounding rural areas to employment, health and education resources in Canberra. How is the upgrade being The Australian and NSW governments have each committed $50 million over four years to upgrade the funded? Barton Highway to improve driver safety, ease congestion and boost freight productivity. The funding will be used to fund investment priorities nominated in the Barton Highway Improvement Strategy 2017, which includes duplicating the highway from the ACT border towards Murrumbateman, as well as future staged upgrades. Has further funding been A further $100 million of Australian Government funding was announced for the Barton Highway in the committed? 2018/19 Federal Budget in May 2018. The announced funding was under the Australian Government’s Roads of Strategic Importance initiative. The duplication business case, which has been forwarded to the Australian Government, will provide guidance as to where the additional $100 million will be best directed. Why is the Barton Highway The Barton Highway is being upgraded to improve road safety. The upgrade will improve journey reliability, being upgraded? ease congestion, improve driver safety and boost freight productivity. -

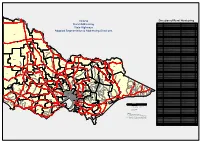

Victoria Rural Addressing State Highways Adopted Segmentation & Addressing Directions

23 0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 MILDURA Direction of Rural Numbering 0 Victoria 00 00 Highway 00 00 00 Sturt 00 00 00 110 00 Hwy_name From To Distance Bass Highway South Gippsland Hwy @ Lang Lang South Gippsland Hwy @ Leongatha 93 Rural Addressing Bellarine Highway Latrobe Tce (Princes Hwy) @ Geelong Queenscliffe 29 Bonang Road Princes Hwy @ Orbost McKillops Rd @ Bonang 90 Bonang Road McKillops Rd @ Bonang New South Wales State Border 21 Borung Highway Calder Hwy @ Charlton Sunraysia Hwy @ Donald 42 99 State Highways Borung Highway Sunraysia Hwy @ Litchfield Borung Hwy @ Warracknabeal 42 ROBINVALE Calder Borung Highway Henty Hwy @ Warracknabeal Western Highway @ Dimboola 41 Calder Alternative Highway Calder Hwy @ Ravenswood Calder Hwy @ Marong 21 48 BOUNDARY BEND Adopted Segmentation & Addressing Directions Calder Highway Kyneton-Trentham Rd @ Kyneton McIvor Hwy @ Bendigo 65 0 Calder Highway McIvor Hwy @ Bendigo Boort-Wedderburn Rd @ Wedderburn 73 000000 000000 000000 Calder Highway Boort-Wedderburn Rd @ Wedderburn Boort-Wycheproof Rd @ Wycheproof 62 Murray MILDURA Calder Highway Boort-Wycheproof Rd @ Wycheproof Sea Lake-Swan Hill Rd @ Sea Lake 77 Calder Highway Sea Lake-Swan Hill Rd @ Sea Lake Mallee Hwy @ Ouyen 88 Calder Highway Mallee Hwy @ Ouyen Deakin Ave-Fifteenth St (Sturt Hwy) @ Mildura 99 Calder Highway Deakin Ave-Fifteenth St (Sturt Hwy) @ Mildura Murray River @ Yelta 23 Glenelg Highway Midland Hwy @ Ballarat Yalla-Y-Poora Rd @ Streatham 76 OUYEN Highway 0 0 97 000000 PIANGIL Glenelg Highway Yalla-Y-Poora Rd @ Streatham Lonsdale -

Falls Prevention Service Directory

Falls Prevention Service Directory Central Adelaide Local Health Network June 2012 Welcome to the fifth edition for the Central Adelaide Local Health Network. The Falls Prevention Service Directory has become a must-have resource for health professionals working with older adults who are at risk of falls. Linking individuals to the right services is easier with maps, common referral forms, clear criteria for referral, a decision making tool and alphabetic listings. Central Adelaide Local Health Network primary health services The Central Adelaide Local Health Network (CALHN) provides care for around 420,000 people living in the central metropolitan area of Adelaide as well as providing a number of state-wide services, and services to those in regional areas. More than 3,000 skilled staff provide high quality client care, education, research and health promoting services. The Central Adelaide Local Health Network (CALHN) provides a range of acute and sub acute health services for people of all ages and covers 19 Statistical Local Areas and 10 Local Government Areas and includes the following: > Royal Adelaide Hospital > The Queen Elizabeth Hospital > Hampstead Rehabilitation Centre > St Margaret’s Rehabilitation Hospital > Ambulatory and Primary Health Care (including Super Clinics) > Sub-Acute > Mental Health Services (under the governance of the Adelaide Metro Mental Health Directorate) We are working hard to build a healthy future for South Australia by striving towards our three strategic goals of better health, better care and better services. What is ‘falls prevention’? Falls represent a common and significant problem, especially in our elderly population. Approximately 30% of community-dwelling older persons fall in Australia each year, resulting in significant mortality and morbidity, as well as increased fear of falling and restriction in physical activity. -

South Road Superway

SOUTH ROAD SUPERWAY ON THE Way The $842M South Road Superway project will be one of Australia’s largest single investment developments and one of the most complex engineering road projects for any freeway. MAIN CONSTRUCTION COMPANIES : John Holland, Leed Engineering & Construction PROJECT END VALUE : $842 million COMPLETION : September 2013 ROAD LEGHTH : 4.8km The Australian and South Australian • The northern end of South Road is Governments are working together to being upgraded as it is a key freight improve transport in South Australia. The route for Adelaide’s major export $842 million South Road Superway project generating industries. is the biggest single investment in a South • South Road is the direct link for industrial Australian road project, and so far the state’s transport hubs: Adelaide Airport, most complex engineering road construction Islington Rail Terminal, Port Adelaide project. This project is under a joint venture and Outer Harbour. between John Holland and Leed Engineering & Construction and is the second stage A purpose built casting yard was of the north-south transport corridor implemented for the project and saved the upgrade which provides a 4.8 kilometre transportation of heavy segments by road. non-stop corridor and incorporates a 2.8 Being able to cast the segments as close kilometre elevated roadway. as possible to the piers ensures minimum interruption to traffic. Land was secured Supporting the local economy, the South Road and the Superway casting yard built for this Superway project has provided more than 2000 purpose at 628-638 South Road. jobs and has supported the growth of local businesses. -

15 February 2007 Ms Zoe Wilson Senior Advisor Office of the Deputy

15 February 2007 Ms Zoe Wilson Senior Advisor Office of the Deputy Prime Minister & Minister for Transport Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Zoe, RE:- Auslink National Land Transport Programme Phase II 1. Introduction – Auslink Generally Infrastructure Partnerships Australia (IPA) appreciates the opportunity to make an informal submission to you in regard to our views on the priority projects for Phase II of the Auslink National Land Transport programme. IPA applauds the Deputy Prime Minister for the foresight and national leadership that has been brought into the infrastructure debate. The Auslink programme is the first time in Australia’s history that the Government has developed a strategic plan to streamline freight links between production and population centres, and producers and our nation’s port facilities. Further, the Auslink programme’s adherence to principles of transparency and contestability in terms of private sector involvement in ownership, financing and operation of national land transport infrastructure assets is commendable. This informal submission will primarily focus on specific projects. In line with the broad policy objective of Auslink, this paper will only focus on projects that will supplement supply networks. However, this informal submission also suggests a number of broader policy issues which may warrant attention as you move to lay the foundations for the next round of investment in Australia’s national transportation system. 2. A Change to the Policy Framework In moving forward toward the second phase of the project, there are a number of policy concepts which may be worth revisiting; As you are in essence seeking specific projects, these policy imperatives will be dealt with succinctly; o Regulatory regime for Infrastructure – Taxation & Equity As a broad policy objective, the Commonwealth could look at models apart from (or in conjunction with) significant s.96 (special purpose) grants to the states. -

Ace Works Layout

South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc. SEATS A Strategic Transport Network for South East Australia SEATS’ holistic approach supports economic development FTRUANNSDPOINRTG – JTOHBSE – FLIUFETSUTYRLE E 2013 SEATS South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc. Figure 1. The SEATS region (shaded green) Courtesy Meyrick and Associates Written by Ralf Kastan of Kastan Consulting for South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc (SEATS), with assistance from SEATS members (see list of members p.52). Edited by Laurelle Pacey Design and Layout by Artplan Graphics Published May 2013 by SEATS, PO Box 2106, MALUA BAY NSW 2536. www.seats.org.au For more information, please contact SEATS Executive Officer Chris Vardon OAM Phone: (02) 4471 1398 Mobile: 0413 088 797 Email: [email protected] Copyright © 2013 SEATS - South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc. 2 A Strategic Transport Network for South East Australia Contents MAP of SEATS region ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary and proposed infrastructure ............................................................................ 4 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 6 2. Network objectives ............................................................................................................................... 7 3. SEATS STRATEGIC NETWORK ............................................................................................................ -

Speed Camera Locations

April 2014 Current Speed Camera Locations Fixed Speed Camera Locations Suburb/Town Road Comment Alstonville Bruxner Highway, between Gap Road and Teven Road Major road works undertaken at site Camera Removed (Alstonville Bypass) Angledale Princes Highway, between Hergenhans Lane and Stony Creek Road safety works proposed. See Camera Removed RMS website for details. Auburn Parramatta Road, between Harbord Street and Duck Street Banora Point Pacific Highway, between Laura Street and Darlington Drive Major road works undertaken at site Camera Removed (Pacific Highway Upgrade) Bar Point F3 Freeway, between Jolls Bridge and Mt White Exit Ramp Bardwell Park / Arncliffe M5 Tunnel, between Bexley Road and Marsh Street Ben Lomond New England Highway, between Ross Road and Ben Lomond Road Berkshire Park Richmond Road, between Llandilo Road and Sanctuary Drive Berry Princes Highway, between Kangaroo Valley Road and Victoria Street Bexley North Bexley Road, between Kingsland Road North and Miller Avenue Blandford New England Highway, between Hayles Street and Mills Street Bomaderry Bolong Road, between Beinda Street and Coomea Street Bonnyrigg Elizabeth Drive, between Brown Road and Humphries Road Bonville Pacific Highway, between Bonville Creek and Bonville Station Road Brogo Princes Highway, between Pioneer Close and Brogo River Broughton Princes Highway, between Austral Park Road and Gembrook Road safety works proposed. See Auditor-General Deactivated Lane RMS website for details. Bulli Princes Highway, between Grevillea Park Road and Black Diamond Place Bundagen Pacific Highway, between Pine Creek and Perrys Road Major road works undertaken at site Camera Removed (Pacific Highway Upgrade) Burringbar Tweed Valley Way, between Blakeneys Road and Cooradilla Road Burwood Hume Highway, between Willee Street and Emu Street Road safety works proposed. -

The Old Hume Highway History Begins with a Road

The Old Hume Highway History begins with a road Routes, towns and turnoffs on the Old Hume Highway RMS8104_HumeHighwayGuide_SecondEdition_2018_v3.indd 1 26/6/18 8:24 am Foreword It is part of the modern dynamic that, with They were propelled not by engineers and staggering frequency, that which was forged by bulldozers, but by a combination of the the pioneers long ago, now bears little or no needs of different communities, and the paths resemblance to what it has evolved into ... of least resistance. A case in point is the rough route established Some of these towns, like Liverpool, were by Hamilton Hume and Captain William Hovell, established in the very early colonial period, the first white explorers to travel overland from part of the initial push by the white settlers Sydney to the Victorian coast in 1824. They could into Aboriginal land. In 1830, Surveyor-General not even have conceived how that route would Major Thomas Mitchell set the line of the Great look today. Likewise for the NSW and Victorian Southern Road which was intended to tie the governments which in 1928 named a straggling rapidly expanding pastoral frontier back to collection of roads and tracks, rather optimistically, central authority. Towns along the way had mixed the “Hume Highway”. And even people living fortunes – Goulburn flourished, Berrima did in towns along the way where trucks thundered well until the railway came, and who has ever through, up until just a couple of decades ago, heard of Murrimba? Mitchell’s road was built by could only dream that the Hume could be convicts, and remains of their presence are most something entirely different. -

Port River Expressway Cycle Path Detour ADVANCE NOTICE

North-South Corridor Northern Connector Project Port River Expressway cycle path detour ADVANCE NOTICE As a part of the Northern Connector Project, The Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure (DPTI) advises that a new cycle path detour will be in place on the Port River Expressway for the eastbound and westbound routes, between Hanson Road and Globe Derby Drive from late August/early September 2017 to late 2019. This will replace the existing eastbound detour and will enable cyclists to continue to travel safely between these locations during the construction of the new bridge connecting the South Road Superway and the Northern Connector, as part of the Southern Interchange. Advanced notice and directional signage will be in place to direct cyclists along the detour. Please refer to the attached map to plan your journey. A further notification will be issued prior to the detour official opening. Thank you for your patience whilst these important works are undertaken. To assist with planning your cycle journey visit http://maps.sa.gov.au/cycleinstead/. # 11827676 Port River Expressway cycle detour For users eastbound and westbound from TBC 2017 to late 2019 LEGEND P O CYCLE DETOUR EASTBOUND ONLY R T (OPEN FROM TBC 2017 TO LATE 2019) W CYCLE DETOUR WESTBOUND ONLY A (OPEN FROM TBC 2017 TO LATE 2019) K E RAILWAY LINE F Ryans Rd I E L Trotters Dr D R N O Use Globe Derby Dr A existing D Dry Creek Linear Trail Use existing pedestrian access to cross Port Wakefield Rd. Dismount bicycle underneath Salisbury Hwy bridge. Use Pedestrian Start crossing eastbound cycle Vater St detour here. -

CHARTER HALL LONG WALE REIT Annexure A: SUEZ Portfolio Overview December 2016 Charter Hall | 2016 Property Overview

October 2015 CHARTER HALL LONG WALE REIT Annexure A: SUEZ portfolio overview December 2016 Charter Hall | 2016 Property overview 12 Lanceley Place, Artarmon, NSW The property comprises a purpose built waste transfer station, with the main building built over two levels. Located in a tightly-held industrial precinct in Artarmon, the property benefits from easy access to the Pacific Highway and Gorehill Freeway. The property is situated in a cul-de-sac among well established industrial properties, approximately 7kms north of the Sydney CBD and 3kms north of North Sydney. Property details Ownership interest 100% Purchase price $17.3 million WALE 30.0 years Occupancy 100% GLA 4,309 sqm Site area 8,726 sqm 20 Davis Road, Wetherill Park, NSW The property comprises a purpose built waste transfer station and weighbridge. The property is surrounded by traditional industrial developments of low to high clearance warehouses and other operations. Wetherill Park is located approximately 30kms west of the Sydney CBD and enjoys excellent access to major Sydney arterial road networks including the Prospect Highway, Cumberland Highway, the M4, M5 and M7 Motorways. Property details Ownership interest 100% Purchase price $10.1 million WALE 10.0 years Occupancy 100% GLA 3,975 sqm Site area 20,490 sqm 2 Charter Hall | 2016 Property overview 201 Newton Road, Wetherill Park, NSW The property comprises an office component over two levels adjoining warehouse amenity. The property is situated on the northern side of Newton Road between Coates Place and Hexham Place. Wetherill Park is located approximately 30kms west of the Sydney CBD and enjoys excellent access to major Sydney arterial road networks including the Prospect Highway, Cumberland Highway, the M4, M5 and M7 Motorways.