The Von Neumann/Stapp Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Motion and Time Study the Goals of Motion Study

Motion and Time Study The Goals of Motion Study • Improvement • Planning / Scheduling (Cost) •Safety Know How Long to Complete Task for • Scheduling (Sequencing) • Efficiency (Best Way) • Safety (Easiest Way) How Does a Job Incumbent Spend a Day • Value Added vs. Non-Value Added The General Strategy of IE to Reduce and Control Cost • Are people productive ALL of the time ? • Which parts of job are really necessary ? • Can the job be done EASIER, SAFER and FASTER ? • Is there a sense of employee involvement? Some Techniques of Industrial Engineering •Measure – Time and Motion Study – Work Sampling • Control – Work Standards (Best Practices) – Accounting – Labor Reporting • Improve – Small group activities Time Study • Observation –Stop Watch – Computer / Interactive • Engineering Labor Standards (Bad Idea) • Job Order / Labor reporting data History • Frederick Taylor (1900’s) Studied motions of iron workers – attempted to “mechanize” motions to maximize efficiency – including proper rest, ergonomics, etc. • Frank and Lillian Gilbreth used motion picture to study worker motions – developed 17 motions called “therbligs” that describe all possible work. •GET G •PUT P • GET WEIGHT GW • PUT WEIGHT PW •REGRASP R • APPLY PRESSURE A • EYE ACTION E • FOOT ACTION F • STEP S • BEND & ARISE B • CRANK C Time Study (Stopwatch Measurement) 1. List work elements 2. Discuss with worker 3. Measure with stopwatch (running VS reset) 4. Repeat for n Observations 5. Compute mean and std dev of work station time 6. Be aware of allowances/foreign element, etc Work Sampling • Determined what is done over typical day • Random Reporting • Periodic Reporting Learning Curve • For repetitive work, worker gains skill, knowledge of product/process, etc over time • Thus we expect output to increase over time as more units are produced over time to complete task decreases as more units are produced Traditional Learning Curve Actual Curve Change, Design, Process, etc Learning Curve • Usually define learning as a percentage reduction in the time it takes to make a unit. -

Quantum Nondemolition Photon Detection in Circuit QED and the Quantum Zeno Effect

PHYSICAL REVIEW A 79, 052115 ͑2009͒ Quantum nondemolition photon detection in circuit QED and the quantum Zeno effect Ferdinand Helmer,1 Matteo Mariantoni,2,3 Enrique Solano,1,4 and Florian Marquardt1 1Department of Physics, Center for NanoScience, and Arnold Sommerfeld Center, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Theresienstrasse 37, D-80333 Munich, Germany 2Walther-Meissner-Institut, Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Walther-Meissner-Str. 8, D-85748 Garching, Germany 3Physics Department, Technische Universität München, James-Franck-Str., D-85748 Garching, Germany 4Departamento de Quimica Fisica, Universidad del Pais Vasco-Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, 48080 Bilbao, Spain ͑Received 17 December 2007; revised manuscript received 15 January 2009; published 20 May 2009͒ We analyze the detection of itinerant photons using a quantum nondemolition measurement. An important example is the dispersive detection of microwave photons in circuit quantum electrodynamics, which can be realized via the nonlinear interaction between photons inside a superconducting transmission line resonator. We show that the back action due to the continuous measurement imposes a limit on the detector efficiency in such a scheme. We illustrate this using a setup where signal photons have to enter a cavity in order to be detected dispersively. In this approach, the measurement signal is the phase shift imparted to an intense beam passing through a second cavity mode. The restrictions on the fidelity are a consequence of the quantum Zeno effect, and we discuss both analytical results and quantum trajectory simulations of the measurement process. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevA.79.052115 PACS number͑s͒: 03.65.Ta, 03.65.Xp, 42.50.Lc I. INTRODUCTION to be already prepared in a certain state. -

Measurement Theories in Quantum Mechanics

Measurement Theories in Quantum Mechanics Cortland M. Setlow March 3, 2006 2 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Intent .. 1 1.2 Overview. 1 1.3 New Theories from Old 3 2 A Brief Review of Mechanics 7 2.1 Newtonian Mechanics: F = mn 8 2.1.1 Newton's Laws of Motion. 8 2.1.2 Mathematics and the Connection to Experiment 9 2.2 Hamiltonian and Lagrangian Mechanics . 10 2.2.1 Lagrangian Mechanics . 10 2.2.2 Hamiltonian Mechanics 12 2.2.3 Conclusions ....... 13 2.3 The Hamiltonian in Quantum Mechanics 14 2.4 The Lagrangian in Quantum Mechanics 14 2.5 Conclusion . .......... 15 3 The Measurement Problem 17 3.1 Introduction . 17 3.2 Quantum Mysteries. 18 i ii CONTENTS 3.2.1 Probability Rules . 18 3.2.2 Probability in Experiments: Diffraction 19 3.3 Conclusions .......... 20 3.3.1 Additional Background 20 3.3.2 Summary ..... 21 4 Solutions to Quantum Problems 23 4.1 Introduction . 23 4.2 Orthodox Theory 23 4.2.1 Measurement in the Orthodox Theory . 24 4.2.2 Criticisms of Orthodox Measurement 24 4.2.3 Conclusions ... 25 4.3 Ghirardi-Rimini-Weber . 25 4.3.1 Dynamics 26 4.3.2 Motivation. 26 4.3.3 Criticisms 28 4.4 Hidden Variables 30 4.4.1 Dynamics of Bohm's Hidden Variables Interpretation. 31 4.4.2 Introducing the Hidden Variables .... 32 4.4.3 But What About von Neumann's Proof? . 33 4.4.4 Relativity and the Quantum Potential 34 4.5 Everett's Relative State Formulation 34 4.5.1 Motivation . -

1 the Principle of Wave–Particle Duality: an Overview

3 1 The Principle of Wave–Particle Duality: An Overview 1.1 Introduction In the year 1900, physics entered a period of deep crisis as a number of peculiar phenomena, for which no classical explanation was possible, began to appear one after the other, starting with the famous problem of blackbody radiation. By 1923, when the “dust had settled,” it became apparent that these peculiarities had a common explanation. They revealed a novel fundamental principle of nature that wascompletelyatoddswiththeframeworkofclassicalphysics:thecelebrated principle of wave–particle duality, which can be phrased as follows. The principle of wave–particle duality: All physical entities have a dual character; they are waves and particles at the same time. Everything we used to regard as being exclusively a wave has, at the same time, a corpuscular character, while everything we thought of as strictly a particle behaves also as a wave. The relations between these two classically irreconcilable points of view—particle versus wave—are , h, E = hf p = (1.1) or, equivalently, E h f = ,= . (1.2) h p In expressions (1.1) we start off with what we traditionally considered to be solely a wave—an electromagnetic (EM) wave, for example—and we associate its wave characteristics f and (frequency and wavelength) with the corpuscular charac- teristics E and p (energy and momentum) of the corresponding particle. Conversely, in expressions (1.2), we begin with what we once regarded as purely a particle—say, an electron—and we associate its corpuscular characteristics E and p with the wave characteristics f and of the corresponding wave. -

Diffraction-Based Interaction-Free Measurements

Quantum Stud.: Math. Found. (2020) 7:145–153 CHAPMAN INSTITUTE FOR https://doi.org/10.1007/s40509-019-00205-6 UNIVERSITY QUANTUM STUDIES REGULAR PAPER Diffraction-based interaction-free measurements Spencer Rogers · Yakir Aharonov · Cyril Elouard · Andrew N. Jordan Received: 18 July 2019 / Accepted: 3 September 2019 / Published online: 14 September 2019 © Chapman University 2019 Abstract We introduce diffraction-based interaction-free measurements. In contrast with previous work where a set of discrete paths is engaged, good-quality interaction-free measurements can be realized with a continuous set of paths, as is typical of optical propagation. If a bomb is present in a given spatial region—so sensitive that a single photon will set it off—its presence can still be detected without exploding it. This is possible because, by not absorbing the photon, the bomb causes the single photon to diffract around it. The resulting diffraction pattern can then be statistically distinguished from the bomb-free case. We work out the case of single- versus double-slit in detail, where the double-slit arises because of a bomb excluding the middle region. Keywords Interaction-free measurement · Bomb-detection · Diffraction · Double-slit · Zeno effect 1 Introduction The first example of a quantum interaction-free measurement (IFM) was given by Elitzur and Vaidman in 1993 [1]. Their famous “bomb tester” is a Mach–Zehnder interferometer which may or may not have a malicious object (“bomb”) blocking one interferometer arm. In the absence of the blockage, one output detector is “dark” (never clicks) due to destructive interference of the two interferometer arms. -

Newtonian Mechanics Is Most Straightforward in Its Formulation and Is Based on Newton’S Second Law

CLASSICAL MECHANICS D. A. Garanin September 30, 2015 1 Introduction Mechanics is part of physics studying motion of material bodies or conditions of their equilibrium. The latter is the subject of statics that is important in engineering. General properties of motion of bodies regardless of the source of motion (in particular, the role of constraints) belong to kinematics. Finally, motion caused by forces or interactions is the subject of dynamics, the biggest and most important part of mechanics. Concerning systems studied, mechanics can be divided into mechanics of material points, mechanics of rigid bodies, mechanics of elastic bodies, and mechanics of fluids: hydro- and aerodynamics. At the core of each of these areas of mechanics is the equation of motion, Newton's second law. Mechanics of material points is described by ordinary differential equations (ODE). One can distinguish between mechanics of one or few bodies and mechanics of many-body systems. Mechanics of rigid bodies is also described by ordinary differential equations, including positions and velocities of their centers and the angles defining their orientation. Mechanics of elastic bodies and fluids (that is, mechanics of continuum) is more compli- cated and described by partial differential equation. In many cases mechanics of continuum is coupled to thermodynamics, especially in aerodynamics. The subject of this course are systems described by ODE, including particles and rigid bodies. There are two limitations on classical mechanics. First, speeds of the objects should be much smaller than the speed of light, v c, otherwise it becomes relativistic mechanics. Second, the bodies should have a sufficiently large mass and/or kinetic energy. -

Measurement Quantum Mechanics and Experiments on Quantum Zeno Effect Carlo Presilla

Annals of Physics PH5535 annals of physics 248, 95121 (1996) article no. 0052 Measurement Quantum Mechanics and Experiments on Quantum Zeno Effect Carlo Presilla Dipartimento di Fisica, UniversitaÁ di Roma ``La Sapienza,'' and INFN, Sezione di Roma, Piazzale A. Moro 2, Rome, Italy 00185 Roberto Onofrio Dipartimento di Fisica ``G. Galilei,'' UniversitaÁ di Padova, and INFN, Sezione di Padova, Via Marzolo 8, Padua, Italy 35131 and Ubaldo Tambini Dipartimento di Fisica, UniversitaÁ di Ferrara, and INFN, Sezione di Ferrara, Via Paradiso 12, Ferrara, Italy 44100 Received June 8, 1995 Measurement quantum mechanics, the theory of a quantum system which undergoes a measurement process, is introduced by a loop of mathematical equivalencies connecting pre- viously proposed approaches. The unique phenomenological parameter of the theory is linked to the physical properties of an informational environment acting as a measurement apparatus which allows for an objective role of the observer. Comparison with a recently reported experiment suggests how to investigate novel interesting regimes for the quantum Zeno effect. 1996 Academic Press, Inc. 1. Introduction The description of the measurement process has been a topic debated from the early developments of quantum mechanics [13]. Besides being a basic issue in the interpretation of the quantum formalism it has also a practical interest in predicting the results of experiments pointing out some paradoxical aspects of the quantum laws when compared to the classical ones. The development of devices whose noise figures are close to the quantum limit makes these experiments within the tech- nological feasibility and demands for a systematization of the theory of quantum measurement with deeper understanding of its experimental implications [4, 5]. -

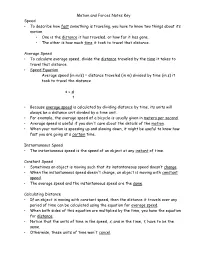

Motion and Forces Notes Key Speed • to Describe How Fast Something Is Traveling, You Have to Know Two Things About Its Motion

Motion and Forces Notes Key Speed • To describe how fast something is traveling, you have to know two things about its motion. • One is the distance it has traveled, or how far it has gone. • The other is how much time it took to travel that distance. Average Speed • To calculate average speed, divide the distance traveled by the time it takes to travel that distance. • Speed Equation Average speed (in m/s) = distance traveled (in m) divided by time (in s) it took to travel the distance s = d t • Because average speed is calculated by dividing distance by time, its units will always be a distance unit divided by a time unit. • For example, the average speed of a bicycle is usually given in meters per second. • Average speed is useful if you don't care about the details of the motion. • When your motion is speeding up and slowing down, it might be useful to know how fast you are going at a certain time. Instantaneous Speed • The instantaneous speed is the speed of an object at any instant of time. Constant Speed • Sometimes an object is moving such that its instantaneous speed doesn’t change. • When the instantaneous speed doesn't change, an object is moving with constant speed. • The average speed and the instantaneous speed are the same. Calculating Distance • If an object is moving with constant speed, then the distance it travels over any period of time can be calculated using the equation for average speed. • When both sides of this equation are multiplied by the time, you have the equation for distance. -

Arxiv:Quant-Ph/0101118V1 23 Jan 2001 Aur 2 2001 12, January N Ula Hsc,Dvso Fhg Nrypyis Fteus Depa U.S

January 12, 2001 LBNL-44712 Von Neumann’s Formulation of Quantum Theory and the Role of Mind in Nature ∗ Henry P. Stapp Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory University of California Berkeley, California 94720 Abstract Orthodox Copenhagen quantum theory renounces the quest to un- derstand the reality in which we are imbedded, and settles for prac- tical rules that describe connections between our observations. Many physicist have believed that this renunciation of the attempt describe nature herself was premature, and John von Neumann, in a major work, reformulated quantum theory as theory of the evolving objec- tive universe. In the course of his work he converted to a benefit what had appeared to be a severe deficiency of the Copenhagen interpre- tation, namely its introduction into physical theory of the human ob- servers. He used this subjective element of quantum theory to achieve a significant advance on the main problem in philosophy, which is to arXiv:quant-ph/0101118v1 23 Jan 2001 understand the relationship between mind and matter. That problem had been tied closely to physical theory by the works of Newton and Descartes. The present work examines the major problems that have appeared to block the development of von Neumann’s theory into a fully satisfactory theory of Nature, and proposes solutions to these problems. ∗This work is supported in part by the Director, Office of Science, Office of High Energy and Nuclear Physics, Division of High Energy Physics, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC03-76SF00098 The Nonlocality Controversy “Nonlocality gets more real”. This is the provocative title of a recent report in Physics Today [1]. -

Gravity, Orbital Motion, and Relativity

Gravity, Orbital Motion,& Relativity Early Astronomy Early Times • As far as we know, humans have always been interested in the motions of objects in the sky. • Not only did early humans navigate by means of the sky, but the motions of objects in the sky predicted the changing of the seasons, etc. • There were many early attempts both to describe and explain the motions of stars and planets in the sky. • All were unsatisfactory, for one reason or another. The Earth-Centered Universe • A geocentric (Earth-centered) solar system is often credited to Ptolemy, an Alexandrian Greek, although the idea is very old. • Ptolemy’s solar system could be made to fit the observational data pretty well, but only by becoming very complicated. Copernicus’ Solar System • The Polish cleric Copernicus proposed a heliocentric (Sun centered) solar system in the 1500’s. Objections to Copernicus How could Earth be moving at enormous speeds when we don’t feel it? . (Copernicus didn’t know about inertia.) Why can’t we detect Earth’s motion against the background stars (stellar parallax)? Copernicus’ model did not fit the observational data very well. Galileo • Galileo Galilei - February15,1564 – January 8, 1642 • Galileo became convinced that Copernicus was correct by observations of the Sun, Venus, and the moons of Jupiter using the newly-invented telescope. • Perhaps Galileo was motivated to understand inertia by his desire to understand and defend Copernicus’ ideas. Orbital Motion Tycho and Kepler • In the late 1500’s, a Danish nobleman named Tycho Brahe set out to make the most accurate measurements of planetary motions to date, in order to validate his own ideas of planetary motion. -

DECOHERENCE AS a FUNDAMENTAL PHENOMENON in QUANTUM DYNAMICS Contents 1 Introduction 152 2 Decoherence by Entanglement with an En

DECOHERENCE AS A FUNDAMENTAL PHENOMENON IN QUANTUM DYNAMICS MICHAEL B. MENSKY P.N. Lebedev Physical Institute, 117924 Moscow, Russia The phenomenon of decoherence of a quantum system caused by the entangle- ment of the system with its environment is discussed from di®erent points of view, particularly in the framework of quantum theory of measurements. The selective presentation of decoherence (taking into account the state of the environment) by restricted path integrals or by e®ective SchrÄodinger equation is shown to follow from the ¯rst principles or from models. Fundamental character of this phenomenon is demonstrated, particularly the role played in it by information is underlined. It is argued that quantum mechanics becomes logically closed and contains no para- doxes if it is formulated as a theory of open systems with decoherence taken into account. If one insist on considering a completely closed system (the whole Uni- verse), the observer's consciousness has to be included in the theory explicitly. Such a theory is not motivated by physics, but may be interesting as a metaphys- ical theory clarifying the concept of consciousness. Contents 1 Introduction 152 2 Decoherence by entanglement with an environment 153 3 Restricted path integrals 155 4 Monitoring of an observable 158 5 Quantum monitoring and quantum Central Limiting Theorem161 6 Fundamental character of decoherence 163 7 The role of consciousness in quantum mechanics 166 8 Conclusion 170 151 152 Michael B. Mensky 1 Introduction It is honor for me to contribute to the volume in memory of my friend Michael Marinov, particularly because this gives a good opportunity to recall one of his early innovatory works which was not properly understood at the moment of its publication. -

Kinematics Definition: (A) the Branch of Mechanics Concerned with The

Chapter 3 – Kinematics Definition: (a) The branch of mechanics concerned with the motion of objects without reference to the forces that cause the motion. (b) The features or properties of motion in an object, regarded in such a way. “Kinematics can be used to find the possible range of motion for a given mechanism, or, working in reverse, can be used to design a mechanism that has a desired range of motion. The movement of a crane and the oscillations of a piston in an engine are both simple kinematic systems. The crane is a type of open kinematic chain, while the piston is part of a closed four‐bar linkage.” Distinguished from dynamics, e.g. F = ma Several considerations: 3.2 – 3.2.2 How do wheels motions affect robot motion (HW 2) 3.2.3 Wheel constraints (rolling and sliding) for Fixed standard wheel Steered standard wheel Castor wheel Swedish wheel Spherical wheel 3.2.4 Combine effects of all the wheels to determine the constraints on the robot. “Given a mobile robot with M wheels…” 3.2.5 Two examples drawn from 3.2.4: Differential drive. Yields same result as in 3.2 (HW 2) Omnidrive (3 Swedish wheels) Conclusion (pp. 76‐77): “We can see from the preceding examples that robot motion can be predicted by combining the rolling constraints of individual wheels.” “The sliding constraints can be used to …evaluate the maneuverability and workspace of the robot rather than just its predicted motion.” 3.3 Mobility and (vs.) Maneuverability Mobility: ability to directly move in the environment.