John Hartford by Art Menius “I Know Why Everybody's Here; They Think I'm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FACULTY Fl FAMOUS

U.S. POSTAGE BULK RATE zoz<z$ I ft '993fHBMTTW PAID °^yi *a ^t8T PERMIT NO. 33 uomxS uopaoo Port Washington, Wis. FBI DOCUMENTS, pg. 3 + WAYSIDE INN CLOSED, pg. 2 + MANGELSDORFF ON CONCERTS, pg. 7 I THE FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL Are you one of the angry ones who bangs his nead against the wall while all your friends talk about "peace and love" and "reforming the system"? Then why not send away for our simple aptitude test and see if you might not have the potential to become a real revolutionary. FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL | the only correspondance school of revolution actually taught by real revolutionaries. You'll receive personal attention in your attempts to off the pig and relate through Marxist-Leninist dialectics to the oppreseed masses. Write in today. If you are one of the first 500 people to answer this ad, you'll receive a free AK-47 and 2000 rounds of ammunition. SAMPLE QUESTIONS FROM THE FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL APTITUDE TEST: Fill in the blanks: Multiple choise: a 1. "Right, The chairman of the standing committee of the Chinese People's 2. "Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Mihn/ NLF will surely" Jj|§ Communist Party is; « 1. Blaze Starr | 2. Gregory Peck 3."1 ... 2 ... 3 ... 4.../ 3. Tina Turner II We don't want your fucking 4. All of the above FACULTY fL Enver Hoxha Alexander Karenskv Kin Agnew Mario Savio Charles Manson Maharishi Mahesh Yogi Nikita Khrushchev Adam Clayton Powell Tim Leary Vance Packard Bo Bolinski Amelia Earhart William Burroughs John Dos Passos &u FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL 233 E. -

Ross Nickerson-Banjoroadshow

Pinecastle Recording Artist Ross Nickerson Ross’s current release with Pin- ecastle, Blazing the West, was named as “One of the Top Ten CD’s of 2003” by Country Music Television, True West Magazine named it, “Best Bluegrass CD of 2003” and Blazing the West was among the top 15 in ballot voting for the IBMA Instrumental CD of the Year in 2003. Ross Nickerson was selected to perform at the 4th Annual Johnny Keenan Banjo Festival in Ireland this year headlined by Bela Fleck and Earl Scruggs last year. Ross has also appeared with the New Grass Revival, Hot Rize, Riders in the Sky, Del McCoury Band, The Oak Ridge Boys, Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and has also picked and appeared with some of the best banjo players in the world including Earl Scruggs, Bela Fleck, Bill Keith, Tony Trischka, Alan Munde, Doug Dillard, Pete Seeger and Ralph Stanley. Ross is a full time musician and on the road 10 to 15 days a month doing concerts , workshops and expanding his audience. Ross has most recently toured England, Ireland, Germany, Holland, Sweden and visited 31 states and Canada in 2005. Ross is hard at work writing new material for the band and planning a new CD of straight ahead bluegrass. Ross is the author of The Banjo Encyclopedia, just published by Mel Bay Publications in October 2003 which has already sold out it’s first printing. For booking information contact: Bullet Proof Productions 1-866-322-6567 www.rossnickerson.com www.banjoteacher.com [email protected] BLAZING THE WEST ROSS NICKERSON 1. -

A Film by Chris Hegedus and D a Pennebaker

a film by Chris Hegedus and D A Pennebaker 84 minutes, 2010 National Media Contact Julia Pacetti JMP Verdant Communications [email protected] (917) 584-7846 FIRST RUN FEATURES The Film Center Building, 630 Ninth Ave. #1213 New York, NY 10036 (212) 243-0600 Fax (212) 989-7649 Website: www.firstrunfeatures.com Email: [email protected] PRAISE FOR KINGS OF PASTRY “The film builds in interest and intrigue as it goes along…You’ll be surprised by how devastating the collapse of a chocolate tower can be.” –Mike Hale, The New York Times Critic’s Pick! “Alluring, irresistible…Everything these men make…looks so mouth-watering that no one should dare watch this film on even a half-empty stomach.” – Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times “As the helmers observe the mental, physical and emotional toll the competition exacts on the contestants and their families, the film becomes gripping, even for non-foodies…As their calm camera glides over the chefs' almost-too-beautiful-to-eat creations, viewers share their awe.” – Alissa Simon, Variety “How sweet it is!...Call it the ultimate sugar high.” – VA Musetto, The New York Post “Gripping” – Jay Weston, The Huffington Post “Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker turn to the highest levels of professional cooking in Kings of Pastry,” a short work whose drama plays like a higher-stakes version of popular cuisine-oriented reality TV shows.” – John DeFore, The Hollywood Reporter “A delectable new documentary…spellbinding demonstrations of pastry-making brilliance, high drama and even light moments of humor.” – Monica Eng, The Chicago Tribune “More substantial than any TV food show…the antidote to Gordon Ramsay.” – Andrea Gronvall, Chicago Reader “This doc is a demonstration that the basics, when done by masters, can be very tasty.” - Hank Sartin, Time Out Chicago “Chris Hegedus and D.A. -

Sunday.Sept.06.Overnight 261 Songs, 14.2 Hours, 1.62 GB

Page 1 of 8 ...sunday.Sept.06.Overnight 261 songs, 14.2 hours, 1.62 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Go Now! 3:15 The Magnificent Moodies The Moody Blues 2 Waiting To Derail 3:55 Strangers Almanac Whiskeytown 3 Copperhead Road 4:34 Shut Up And Die Like An Aviator Steve Earle And The Dukes 4 Crazy To Love You 3:06 Old Ideas Leonard Cohen 5 Willow Bend-Julie 0:23 6 Donations 3 w/id Julie 0:24 KSZN Broadcast Clips Julie 7 Wheels Of Love 2:44 Anthology Emmylou Harris 8 California Sunset 2:57 Old Ways Neil Young 9 Soul of Man 4:30 Ready for Confetti Robert Earl Keen 10 Speaking In Tongues 4:34 Slant 6 Mind Greg Brown 11 Soap Making-Julie 0:23 12 Volunteer 1 w/ID- Tony 1:20 KSZN Broadcast Clips 13 Quittin' Time 3:55 State Of The Heart Mary Chapin Carpenter 14 Thank You 2:51 Bonnie Raitt Bonnie Raitt 15 Bootleg 3:02 Bayou Country (Limited Edition) Creedence Clearwater Revival 16 Man In Need 3:36 Shoot Out the Lights Richard & Linda Thompson 17 Semicolon Project-Frenaudo 0:44 18 Let Him Fly 3:08 Fly Dixie Chicks 19 A River for Him 5:07 Bluebird Emmylou Harris 20 Desperadoes Waiting For A Train 4:19 Other Voices, Too (A Trip Back To… Nanci Griffith 21 uw niles radio long w legal id 0:32 KSZN Broadcast Clips 22 Cold, Cold Heart 5:09 Timeless: Hank Williams Tribute Lucinda Williams 23 Why Do You Have to Torture Me? 2:37 Swingin' West Big Sandy & His Fly-Rite Boys 24 Madmax 3:32 Acoustic Swing David Grisman 25 Grand Canyon Trust-Terry 0:38 26 Volunteer 2 Julie 0:48 KSZN Broadcast Clips Julie 27 Happiness 3:55 So Long So Wrong Alison Krauss & Union Station -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 12 AUGUST 1ST, 2016 August 1, 2016 Up the Ladder INCOMING LETTERS Written by Paul McGowan I am responding to the recent article on DACs and the quick brush-off of ladder DACs. (Richard Murison’s “My Kingdom for a DAC”, Richard didn’t brush off ladder DACs so much as say that they were damned hard to build properly --Ed.) There are several R2R or ladder DACs on the market and in my opinion and that of many others they are far superior to any delta-sigma DAC on the market. The best example is the Audio-GD Master 7 dac. Also, the great Audio Note DACs are ladder DACs. These DACs have a musicallity that delta- sigma DACs dream about. Delta-sigma dacs are used mostly because R2R chips are simply too difficult and expensive to make.The old R2R chips are expensive, hard to find and no longer in production. I believe Mytek is making an R2R chip and Audio Note has one in development. Did a recent comparison of my Master 7 with a friend’s DCS stack and even he thought the Master 7 was better. The DCS is 10 times the price. Yes, a ladder DAC will not do DSD, but for me that is no great loss. Alan Hendler Doesn't Like Tchaikovsky Either Three cheers for Mr. Schenbeck. He writes concisely and entertainingly and, with his adroit embedding of musical examples, uses the electronic magazine format as it should be used. I look forward to each of his contributions. Never much liked Tchaikovsky either. -

Music K-8 Marketplace 2021 Spring Update Catalog

A Brand New Resource For Your Music Classroom! GAMES & GROOVES FOR BUCKET BAND, RHYTHM STICKS, AND LOTS OF JOYOUS INSTRUMENTS by John Riggio and Paul Jennings Over the last few years, bucket bands have grown greatly in popularity. Percussion is an ideal way to teach rhythmic concepts and this low-cost percussion ensemble is a great way to feel the joy of group performance without breaking your budget. This unique new product by John Riggio and Paul Jennings is designed for players just beyond beginners, though some or all players can easily adapt the included parts. Unlike some bucket band music, this is written with just one bucket part, intended to be performed on a small to medium-size bucket. If your ensemble has large/bass buckets, they can either play the written part or devise a more bass-like part to add. Every selection features rhythm sticks, though the tracks are designed to work with just buckets, or any combination of the parts provided. These change from tune to tune and include Boomwhackers®, ukulele, cowbell, shaker, guiro, and more. There are two basic types of tunes here, games and game-like tunes, and grooves. The games each stand on their own, and the grooves are short, repetitive, and fun to play, with many repeats. Some songs have multiple tempos to ease learning. And, as you may have learned with other music from Plank Road Publishing and MUSIC K-8, we encourage and permit you to adapt all music to best serve your needs. This unique collection includes: • Grizzly Bear Groove • Buckets Are Forever (A Secret Agent Groove) • Grape Jelly Groove • Divide & Echo • Build-A-Beat • Rhythm Roundabout ...and more! These tracks were produced by John Riggio, who brings you many of Plank Road’s most popular works. -

The Twenty Greatest Music Concerts I've Ever Seen

THE TWENTY GREATEST MUSIC CONCERTS I'VE EVER SEEN Whew, I'm done. Let me remind everyone how this worked. I would go through my Ipod in that weird Ipod alphabetical order and when I would come upon an artist that I have seen live, I would replay that concert in my head. (BTW, since this segment started I no longer even have an ipod. All my music is on my laptop and phone now.) The number you see at the end of the concert description is the number of times I have seen that artist live. If it was multiple times, I would do my best to describe the one concert that I considered to be their best. If no number appears, it means I only saw that artist once. Mind you, I have seen many artists live that I do not have a song by on my Ipod. That artist is not represented here. So although the final number of concerts I have seen came to 828 concerts (wow, 828!), the number is actually higher. And there are "bar" bands and artists (like LeCompt and Sam Butera, for example) where I have seen them perform hundreds of sets, but I counted those as "one," although I have seen Lecompt in "concert" also. Any show you see with the four stars (****) means they came damn close to being one of the Top Twenty, but they fell just short. So here's the Twenty. Enjoy and thanks so much for all of your input. And don't sue me if I have a date wrong here and there. -

Primary Music Previously Played

THE AUSTRALIAN SCHOOL BAND & ORCHESTRA FESTIVAL MUSIC PREVIOUSLY PLAYED HELD ANNUALLY THROUGH JULY, AUGUST & SEPTEMBER A non-competitive, inspirational and educational event Primary School Concert and Big Bands WARNING: Music Directors are advised that this is a guide only. You should consult the Festival conditions of entry for more specific information as to the level of music required in each event. These information on these lists was entered by participating bands and may contain errors. Some of the music listed here may be regarded as too easy or too difficult for the section in which it is listed. Playing music which is not suitable for the section you have entered may result in you being awarded a lower rating or potentially ineligible for an award. For any further advice, please feel free to contact the General Manager of the Festival at [email protected], visit our website at www.asbof.org.au or contact one of the ASBOF Advisory Panel Members. www.asbof.org.au www.asbof.org.au I [email protected] I PO Box 833 Kensington 1465 I M 0417 664 472 Lithgow Music Previously Played Title Composer Arranger Aust A L'Eglise Gabriel Pierne Kenneth Henderson A Night On Bald Mountain Modest Moussorgsky John Higgins Above the World Rob GRICE Abracadabra Frank Tichelli Accolade William Himes William Himes Aerostar Eric Osterling Air for Band Frank Erickson Ancient Dialogue Patrick J. Burns Ancient Voices Michael Sweeney Ancient Voices Angelic Celebrations Randall D. Standridge Astron (A New Horizon) David Shaffer Aussie Hoedown Ralph Hultgren -

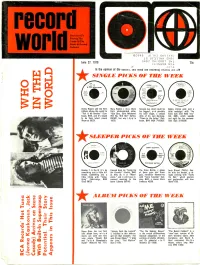

Record World

record tWODedicated To Serving The Needs Of The Music & Record Industry x09664I1Y3 ONv iS Of 311VA ZPAS 3NO2 ONI 01;01 3H1 June 21, 1970 113N8V9 NOti 75c - In the opinion of the eUILIRS,la's wee% Tne itmuwmg diCtie SINGLE PICKS OF THE WEEK EPIC ND ARMS CAN EVER HOLD YOU CORBYVINTON Kenny Rogers and the First Mary Hopkin sings Doris Nilsson has what could be Bobby Vinton gets justa Edition advise the world to Day'sphilosophicaloldie, his biggest, a n dpossibly littlenostalgicwith"No "TellItAll Brother" (Sun- "Que Sera, Sera (Whatever hisbest single,a unique Arms Can Ever Hold You" beam, BMI), and it's bound WillBe, WillBe)" (Artist, dittyofhis own devising, (Gil, BMI),whichsounds tobe theirlatestsmash ASCAP), her way (A p p le "Down to the Valley" (Sun- just right for the summer- (Reprise 0923). 1823). beam, BM!) (RCA 74-0362). time (Epic 5-10629). SLEEPER PICKS OF THE WEEK SORRY SUZANNE (Jan-1111 Auto uary, Embassy BMI) 4526 THE GLASS BOTTLE Booker T. & the M. G.'s do Canned Heat do "Going Up The Glass Bottle,a group JerryBlavat,Philly'sGea something just alittledif- the Country" (Metric, BMI) ofthreeguysandthree for with the Heater,isal- ferent,somethingjust a astheydo itin"Wood- gals, introduce themselves ready clicking with "Tasty littleliltingwith"Some- stock," and it will have in- with "Sorry Suzanne" (Jan- (To Me),"whichgeators thing" (Harrisongs, BMI) creasedmeaningto the uary, BMI), a rouser (Avco andgeatoretteswilllove (Stax 0073). teens (Liberty 56180). Embassy 4526). (Bond 105). ALBUM PICKS OF THE WEEK DianaRosshasherfirst "Johnny Cash the Legend" "The Me Nobody Knows" "The Naked Carmen" isa solo album here, which is tributed in this two -rec- isthe smash off-Broadway "now"-ized versionofBi- startsoutwithherfirst ord set that includes' Fol- musical adaptation of the zet's timeless opera. -

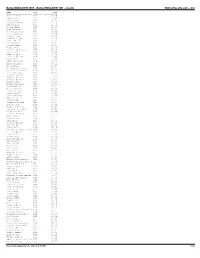

Bolderboulder 2005 - Bolderboulder 10K - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

BolderBOULDER 2005 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Michael Aish M28 30:29 Jesus Solis M21 30:45 Nelson Laux M26 30:58 Kristian Agnew M32 31:10 Art Seimers M32 31:51 Joshua Glaab M22 31:56 Paul DiGrappa M24 32:14 Aaron Carrizales M27 32:23 Greg Augspurger M27 32:26 Colby Wissel M20 32:36 Luke Garringer M22 32:39 John McGuire M18 32:42 Kris Gemmell M27 32:44 Jason Robbie M28 32:47 Jordan Jones M23 32:51 Carl David Kinney M23 32:51 Scott Goff M28 32:55 Adam Bergquist M26 32:59 trent r morrell M35 33:02 Peter Vail M30 33:06 JOHN HONERKAMP M29 33:10 Bucky Schafer M23 33:12 Jason Hill M26 33:15 Avi Bershof Kramer M23 33:17 Seth James DeMoor M19 33:20 Tate Behning M23 33:22 Brandon Jessop M26 33:23 Gregory Winter M26 33:25 Chester G Kurtz M30 33:27 Aaron Clark M18 33:28 Kevin Gallagher M25 33:30 Dan Ferguson M23 33:34 James Johnson M36 33:38 Drew Tonniges M21 33:41 Peter Remien M25 33:45 Lance Denning M43 33:48 Matt Hill M24 33:51 Jason Holt M18 33:54 David Liebowitz M28 33:57 John Peeters M26 34:01 Humberto Zelaya M30 34:05 Craig A. Greenslit M35 34:08 Galen Burrell M25 34:09 Darren De Reuck M40 34:11 Grant Scott M22 34:12 Mike Callor M26 34:14 Ryan Price M27 34:15 Cameron Widoff M35 34:16 John Tribbia M23 34:18 Rob Gilbert M39 34:19 Matthew Douglas Kascak M24 34:21 J.D. -

Rotten Taters Is a Snapshot of Some of the Material Mike Has Begun to Do in His Solo Endeavors

MIKE COMPTON “This recording is pure gold, through and through.” - Glen Herbert, KDHX Rotten Taters is a snapshot of some of the material Mike has begun to do in his solo endeavors. It’s a project which for the first time lets us see something that we’ve only glimpsed in the past Compton playing by himself, unaccompanied and undirected. And it’s simply stellar. For Compton, it’s all about rhythm, with the mandolin serving principally as a rhythmic instrument rather than a melodic one. These days, for this style of playing, he is the player that all others are compared to; if you play old-time or traditional bluegrass mandolin, you want to play like Mike Compton. Here, for the first time, is pure, unadorned Compton. Of the fifteen songs and tunes here, six are from Compton’s own pen. Tracks like “How Do you Want Your Rollin’ Done” and “I’ll Tell you About the Women” seem, in a sense, like portraits of Compton himself, his effervescence and humor laid bare. Of note, the cut “Forever Has Come to and End” is stark and longing, excellently accompanied only by mandolin chords and cross-picking, bringing out the desperation of the lyric. “Jenny Lynn” is a tribute to Monroe, staying close to Monroe’s style, as is the original piece “Wood Butcher’s Walkabout”, which is like a master class in the slides that are a hallmark of Compton’s playing. “Mike has taken a passel of influences -- “old Instruments Used on This Recording: time fiddle tunes, rock salt and nails Paul Duff F5 Mandolin, 2011. -

Classical Gas Recordings and Releases Releases of “Classical Gas” by Mason Williams

MasonMason WilliamsWilliams Full Biography with Awards, Discography, Books & Television Script Writing Releases of Classical Gas Updated February 2005 Page 1 Biography Mason Williams, Grammy Award-winning composer of the instrumental “Classical Gas” and Emmy Award-winning writer for “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour,” has been a dynamic force in music and television circle since the 1960s. Born in Abilene, Texas in 1938, Williams spent his youth divided between living with his 1938 father in Oklahoma and his mother in Oregon. His interest in music began when, as a teenager, he to 1956 became a fan of pop songs on the radio and sang along with them for his own enjoyment. In high Oklahoma school, he sang in the choir and formed his first group, an a capella quartet that did the 1950’s City style pop and rock & roll music of the era. They called themselves The Imperials and The to L.A. Lamplighters. The other group members were Diana Allen, Irving Faught and Larry War- ren. After Williams was graduated from Northwest Classen High School in Oklahoma City in 1956, he and his lifelong friend, artist Edward Ruscha, drove to Los Angeles. There, Williams attended Los Angeles City College as a math major, working toward a career as an insurance actuary. But he spent almost as much time attending musical events, especially jazz clubs and concerts, as he did studying. This cultural experience led him to drop math and seek a career in music. Williams moved back to Oklahoma City in 1957 to pursue his interest in music by taking a crash course in piano for the summer.