Failing Better

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D'art Ambition D'art Alighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony

Ambition d’art AmbitionAlighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony Cragg, Luciano Fabro, Yona Friedman, Anish Kapoor, On Kawara, Martha Rosler, Jeff Wall, Lawrence Weiner d’art16 May – 21 September 2008 The Institut d’art contemporain aspect (an anniversary) and the is celebrating its 30th anniversary setting – the inauguration of an in 2008 and on this occasion exhibition in the artistico-political has invited its founder, context of the 2000s – it is aimed Jean Louis Maubant, to design at shedding light on what the an exhibition, accompanied by an ‘ambition’ of art and its ‘world’ important publication. might be. The exhibition Ambition d’art, held in partnership with the The retrospective dimension Rhône-Alpes Regional Council of the event is presented above and the town of Villeurbanne, is a all in the two volumes (Alphabet strong and exceptional event for and Archive) of the publication to the Institute: beyond the anecdotal which it has given rise. Institut d’art contemporain, Villeurbanne www.i-art-c.org Any feedback in the exhibition is Yona Friedman, Jordi Colomer) or less to commemorate past history because they have hardly ever been than to give present and future shown (Martha Rosler, Alighiero history more density. In fact, many Boetti, Jeff Wall). Other works have of the works shown here have already been shown at the Institut never been seen before. and now gain fresh visibility as a result of their positioning in space and their artistic company (Luciano Fabro, Daniel Buren, Martha Rosler, Ambition d’art Tony Cragg, On Kawara). For the exhibition Ambition d’art, At the two ends of the generation Jean Louis Maubant has chosen chain, invitations have been eleven artists for the eleven rooms extended to both Jordi Colomer of the Institut d’art contemporain. -

Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Kicks Off Annual Eight-Day

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: March 4, 2015 Oname Thompson (703) 864-5980 cell [email protected] Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Kicks Off Annual Eight-Day, Seven- Country USO Spring Troop Visit and Brings Warmth to Troops Early Chuck Pagano, Andrew Luck, Dwayne Allen, David DeCastro, Diana DeGarmo, Ace Young, Dennis Haysbert, Miss America 2015 Kira Kazantsev, Phillip Phillips and Wee Man join Admiral James Winnefeld in Extending America’s Thanks ARLINGTON, VA (Mar. 4, 2015) – Nothing marks the end of a blistering, cold winter quite like the annual USO Spring Troop Visit led by the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral James A. Winnefeld, Jr. The eight-day, seven country USO tour is designed to appeal to troops of all ages and bring a much needed touch of home to those serving abroad. This year’s variety-style USO tour is a fusion of music, comedy and heartfelt messages of support featuring Indianapolis Colts head coach Chuck Pagano, quarterback Andrew Luck and tight end Dwayne Allen; Pittsburgh Steelers guard David DeCastro; “American Idol” alumni Diana DeGarmo and Ace Young; American film, stage and television actor Dennis Haysbert; Miss America 2015 Kira Kazantsev; platinum recording artist and season 11 “American Idol” winner Phillip Phillips; as well as motion picture and television personality Jason “Wee Man” Acuna. ***USO photo link below with images added daily*** DETAILS: The tour will visit various countries in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia Pacific, as well as an aircraft carrier at sea. Three days into the moment-filled USO tour, the group has visited two military bases and created #USOMoments for more than 1,300 troops and military families. -

1998-Fall.Pdf

Fall 98 Cover F&B_ Fall 98 Cover F&B 12/24/15 9:45 AM Page 3 Chicago EXPLORING NATURE & CULTURE WFALILL 19D98 ERNES S FIRE AS A FRIEND • T HINKING LIKE A SEED Fall cov 02 - 12_ Fall cov 02 - 12 12/24/15 10:10 AM Page cov2 is Chicago Wilderness? Chicago Wilderness is some of the finest and most signifi - cant nature in the temperate world, with roughly 200,000 acres of protected natural lands harboring native plant and animal communities that are more rare—and their survival more globally threatened—than the tropical rain forests. CHICAGO WILDERNESS is an unprecedented alliance of more than 60 public and private organizations working together to study and restore, protect and manage the precious natural resources of the Chicago region for the benefit of the public. Chicago WILDERNES S is a new quarterly magazine that seeks to articulate a vision of regional identity linked to nature and our natural heritage, to celebrate and promote the rich nat - ural areas of this region, and to inform readers about the work of the many organizations engaged in collaborative conservation. Fall cov 02 - 12_ Fall cov 02 - 12 12/24/15 10:10 AM Page 1 CHICAGO WILDERNESS A Regional Nature Reserve Keeping the Home Fires Burning or generations of us inculcated with the gospel according them, both by white men and by Indians—par accident; and Fto Smokey, setting fire to woods and prairies on purpose yet many more where it is voluntarily done for the purpose amounts to blasphemy. Yet those who love the land have of getting a fresh crop of grass, for the grazing of their horses, been wrestling with some new ideas about fire—new ideas and also for easier travelling during the next summer.” that are very old. -

November 23Rd, 2010 Gene Beery

Gene Beery at Algus Greenspon Within Gene Beery’s conceptual language-based paintings, there always seems to be some kind of joke—and not always one that the viewer is in on. Among the pieces included in the artist’s 50-year retrospective was Note (1970), in which the words “NOTE: MAKE A PAINTING OF A NOTE AS A PAINTING” are rendered in puffy, candy-colored letters on a pale background with a black framelike border. In another, the words “life without a sound sense of tra can seem like an incomprehensible nup” (1994) are written in black capital letters on white; the canvas is divided by a thick black line, which cuts through the lines of text so that the reversed words “art” and “pun” are separated from the rest. Gene Beery, Note, 1970, acrylic on canvas, 34 x 42 inches. The exhibition began with works from the late 1950s, when Beery, then employed as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art, was “discovered” by James Rosenquist and Sol LeWitt. An “artist’s artist,” he was championed by artists who were, and would remain, better known than he. After a 1963 show at Alexander Iolas Gallery in New York, Beery moved to the Sierra Nevada mountains, where he still lives. While other artists using text and numbers who emerged in the 1960s—Lawrence Weiner, Joseph Kosuth, On Kawara, for example—produced mostly cerebral works lacking evidence of the artist’s hand, Beery seemingly poked fun at the high Conceptualism of the day. He continued to make his uniquely homespun and humorously irreverent canvases, the rawness of their execution a throwback to the Abstract Expressionists. -

Download Transcript (PDF)

KAWARA: EXHIBITION OVERVIEW Jeffrey Weiss: On Kawara was a key figure in the art of the 1960s in particular. He began working in Japan and continued work in many other cities, finally settling in New York in the mid-’60s, where he was part of the community of Conceptual art during that period of time. He knew a lot of artists that we associate with Conceptualism including Sol LeWitt and Hanne Darboven, Joseph Kosuth and Dan Graham. It’s easy to associate his work, then, with the rise of Conceptualism, although Kawara’s work, when you examine it closely, stands well apart. This exhibition was organized in cooperation with the artist. And I really wanted to show every category of Kawara’s production since around 1964. We don’t call it a retrospective because Kawara’s work is based on time, on the passage of time. So the idea of the retrospective actually doesn’t apply in the conventional sense. Anne Wheeler: We heard from a number of his friends and colleagues from even years ago that it had always been his dream to have a show at the Guggenheim because of the cyclical nature of time and the way that the building represents that in the way that you can move throughout the chronology of his work. In organizing the show we are moving more or less chronologically through the series of his works, starting in the High Gallery with works from 1963 to ’65. Jeffrey Weiss: We’re also showing Paris–New York Drawings, which he produced in Paris and New York, where he was living—both places. -

Sol Lewitt's Wall Drawings

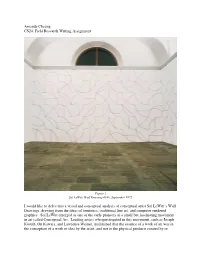

Amanda Cheung CS24: Field Research Writing Assignment Figure 1 Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing #146, September 1972 I would like to delve into a visual and conceptual analysis of conceptual artist Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawings, drawing from the ideas of semiotics, traditional fine art, and computer rendered graphics. Sol LeWitt emerged as one of the early pioneers of a small but fascinating movement in art called Conceptual Art. Leading artists who participated in this movement, such as Joseph Kosuth, On Kawara, and Lawrence Weiner, maintained that the essence of a work of art was in the conception of a work or idea by the artist, and not in the physical products created by or representing the idea. For example, in Joseph Kosuth’s “One and Three Chairs,” the artwork is the idea of the chair, represented the word “chair,” a photograph of a chair, and the dictionary definition of chair. The work explores of the idea of the signifier, signified, and referent as studied in semiotics, and questions the role of the artist in creating a work; can he simply conceive an idea and let it be art, aside from any physical product? In Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawings, such as the one pictured in Figure 1, the essence of the work lay in the conception of the specific lines/shapes to be drawn on a wall, and not in the final product. LeWitt’s process involved conceiving the idea for the specific wall drawing and giving instructions to workers who executed the drawings in the exhibition spaces. Thus, a single “Wall Drawing” work would appear differently in different exhibitions because it would be executed by different people and in different spaces. -

Documenta 11

1/21/2015 Frieze Magazine | Archive | Documenta 11 Documenta 11 About this article Documenta 11 Published on 09/09/02 By Thomas McEvilley Each of artistic director Okwui Enwezor’s six co-curators - Sarat Maharaj, Octavio Zaya, Carlos Basualdo, Ute Meta Bauer, Susanne Ghez and Mark Nash - spoke briefly, followed by Enwezor himself. Maharaj identified the point of art today as ‘knowledge production’ and the point of this exhibition as ‘thinking the other’; Nash declared that the exhibition aimed to explore ‘issues of dislocation and migration’ (‘We’re all becoming transnational subjects’, he observed); Ghez stressed the unusual fact that as many as 70% of the works in the show were made explicitly for the Back to the main site occasion; Basualdo spoke of ‘establishing a new geography, or topology, of culture’; and Bauer spoke of ‘deterritorialization’. Finally, Enwezor began his reflections by referring to Chinua Achebe’s classic novel of pre-colonial Africa Things Fall Apart (1958). He spoke of the emergence of post-colonial identity, and said that he and his colleagues had aimed at something much larger than an art exhibition: they were seeking to find out what comes after imperialism. These remarks were significant because Documenta, along with the Venice Biennale, is one of the foremost venues at which the current cultural politics of the art world is laid out. In a sense the agenda proclaimed by these curators gave one a sense of déjà vu; or rather, it seemed not exactly to usher in a new era but to set a seal on an era first announced long ago. -

On Kawara Unanswered Questions Personal Structures Art Projects # 04 on Kawara

ON KAWARA UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Personal Structures Art Projects # 04 ON KAWARA ON KAWARA UNANSWERED QUESTIONS UNANSWERED QUESTIONS This book is the documentation of Personal Structures Art Projects #04. It has been published as a limited edition. The edition comprises 250 copies of which 50 DeLuxe, numbered from 1 to 50, and 50 DeLuxe hors commerce, numbered from I to L. The 150 Standard copies are numbered from 51 to 200. Each item of this limited edition consists of a book and a CD in a case, housed together in a cassette. The DeLuxe edition additionally contains a postcard with a question for On Kawara, returned to sender. This limited edition has been divided as follows: # 1-50: DeLuxe edition: Luïscius Antiquarian Booksellers, Netherlands # 51-200: Standard edition: Luïscius Antiquarian Booksellers, Netherlands HC I-L: Not for trade © 2009-2011. Text by Karlyn De Jongh © 2007-2009. Questions by the authors All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechan- ical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission of the editor. Concept by Rene Rietmeyer and Sarah Gold Design by Karlyn De Jongh Printed and bound under the direction of Andreas Krüger, Germany Production in coöperation with Christien Bakx, www.luiscius.com Published by GlobalArtAffairs Foundation, www.globalartaffairs.org KARLYN DE JONGH ON Kawara: UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Today is Saturday, 19 December 2009, and right now I am in my apart- ment in Venice, Italy. My name is Karlyn De Jongh. I am an indepen- dent curator and author from the Netherlands and I have spent two years working on the project Unanswered Questions to On Kawara. -

The Chapel Bell Presented by the Maple Street Chapel Preservation Society, Inc

The Chapel Bell Presented by the Maple Street Chapel Preservation Society, Inc. Volume 15, Issue No. 3 Summer, 2014 A New Major Chapel Initiative By Ken Bohl, Facilities Director Consider this interesting discussion I had. I was talking to a historical restoration engineer, someone who managed major projects. The subject was a stunningly beautiful church in New Jersey. The church was originally built without a steeple, and a steeple was added later. The building began to fail structurally under the added weight, the steeple sinking down, and the walls spreading. Imagine what a major costly project it was to lift up the steeple, add additional support, and draw the walls back in. It cost hundreds of thousand of dollars and took six months. But it was successful. Then a couple months later they replaced the gutters, and decided to install historic copper gutters, which are soldered together on-site. Can you guess what’s next? By the time the fire department arrived, the church was completely engulfed in flames, and was a total loss. Did that catch you by surprise? Well, that’s exactly the way it happens in real life. The last thing you expected, just when all seemed well. What if the next time you drove through downtown Lombard our beloved Chapel was gone? Can you even imagine not seeing it on that corner where it has stood for 144 years? What if it no longer stood as the beckoning landmark that holds our precious community history and personal memories? The thought of this scenario makes me heartsick. -

Georges Perec and on Kawara: Endotic Extravagance in Literature, Art, and Dance Leslie Satin New York University ______

Satin: Endotic Extravagance 50 Georges Perec and On Kawara: Endotic Extravagance in Literature, Art, and Dance Leslie Satin New York University _____________________________________ Abstract: This article analyzes the work of Georges Perec and On Kawara, two artists who have radically recast our understanding of space and time in literature and the visual arts, through the lens of the author’s post-modern dance practice and scholarship. Both artists, deeply affected by the chaos of World War II, began working in the mid- twentieth century: experimental author Georges Perec (1936-1983), known for his affiliation with OuLiPo (Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle, or Workshop for Potential Literature), the organization founded in 1960 to ratchet up the possibilities for conceiving and creating utterly new, or ‘potential’, literature, and On Kawara (1932- 2014), the Conceptual artist known for his large-scale recasting of personal and historical time, and his conversion of ‘private life’ into vast archives of documentary recording. The article looks both at spatial elements in the work of these artists, and at spatialized responses to their words and objects. It investigates Perec’s and Kawara’s divergent ideas of the everyday, as articulated through their practices—particularly their commitment to compositional scores and games exemplifying the ludic, and their insistence on the importance of seeing and noticing—and the implications of those practices, and the work they produced, regarding facticity, embodiment, self-representation, transformation, and, above all, the ongoing articulation of space and, by extension, time. Informed by work in human geography; affect, literary, and performance theory; and phenomenology, and by the writer’s experience in dance as a practice and area of scholarship, the article links these practices and ideas to those of post-modern dance to explore the fluid relationships among space, movement, bodies, and objects. -

“Sh-Boom” and the Bomb: a Postwar Call and Response

1 “Sh-Boom” and the Bomb: A Postwar Call and Response Raging fire balls, vaporized islands, ear-splitting clamor, mushroom clouds, shock waves, moral abomination, massive guilt, backyard bomb shelters, and thinking the unthinkable—all of these were part of the psychological and emotional Zeitgeist of Postwar America. Test Able, the first atom-bomb test off Bikini in the Marshall Islands, took place in the summer of 1946. At that time, many Americans feared the consequences. Some believed gravity would be destroyed, or that the ocean would turn to gas, or perhaps an underwater explosion would blow a hole in the bottom of the sea and cause it to run completely out. Others expected earthquakes, tidal waves, or radioactive waves that would, a Portland, Oregon taxi driver feared, “peel his skin like a banana.”1 None of these suspicions materialized, though the site of the explosion became the name of a woman’s two-piece bathing suit. In Homeward Bound, Elaine Tyler May links the photograph of Hollywood sex symbol Rita Hayworth that was physically attached to the bomb to the “name for the abbreviated swimsuit the female ‘bombshells’ would wear. The designer of the revealing suit,” she says, “chose the name ‘bikini’ four days after the bomb was dropped to suggest the swimwear’s explosive potential.”2 William O’Neill, the author of American High, points out that nuclear weaponry at that time was a concern so frightening that “popular culture absorbed and trivialized” it.3 Looking back, it seems excessive to have worried so about a fission bomb. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

FROM SERIAL DEATH TO PROCEDURAL LOVE: A STUDY OF SERIAL CULTURE By STEPHANIE BOLUK A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Stephanie Boluk 2 For my mum 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS One of the reasons I chose to come to the University of Florida was because of the warmth and collegiality I witnessed the first time I visited the campus. I am grateful to have been a member of such supportive English department. A huge debt of gratitude is owed to my brilliant advisor Terry Harpold and rest of my wonderful committee, Donald Ault, Jack Stenner, and Phil Wegner. To all of my committee: a heartfelt thank you. I would also like to thank all the members of Imagetext, Graduate Assistants United, and Digital Assembly (and its predecessor Game Studies) for many years of friendship, fun, and collaboration. To my friends and family, Jean Boluk, Dan Svatek, and the entire LeMieux clan: Patrick, Steve, Jake, Eileen, and Vince, I would not have finished without their infinite love, support, patience (and proofreading). 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... 11 Serial Ancestors.....................................................................................................