Diplomacy in Crisis: the Trump Administration's Decimation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Policy Scan 2021

US Policy Scan 2021 1 • US Policy Scan 2021 Introduction Welcome to Dentons 2021 Policy Scan, an in-depth look at policy a number of Members of Congress and Senators on both sides of at the Federal level and in each of the 50 states. This document the aisle and with a public exhausted by the anger and overheated is meant to be both a resource and a guide. A preview of the rhetoric that has characterized the last four years. key policy questions for the next year in the states, the House of Representatives, the Senate and the new Administration. A Nonetheless, with a Congress closely divided between the parties resource for tracking the people who will be driving change. and many millions of people who even now question the basic legitimacy of the process that led to Biden’s election, it remains to In addition to a dive into more than 15 policy areas, you will find be determined whether the President-elect’s goals are achievable brief profiles of Biden cabinet nominees and senior White House or whether, going forward, the Trump years have fundamentally staff appointees, the Congressional calendar, as well as the and permanently altered the manner in which political discourse Session dates and policy previews in State Houses across the will be conducted. What we can say with total confidence is that, in country. We discuss redistricting, preview the 2022 US Senate such a politically charged environment, it will take tremendous skill races and provide an overview of key decided and pending cases and determination on the part of the President-elect, along with a before the Supreme Court of the United States. -

Open Hearing: Nomination of Gina Haspel to Be the Director of the Central Intelligence Agency

S. HRG. 115–302 OPEN HEARING: NOMINATION OF GINA HASPEL TO BE THE DIRECTOR OF THE CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY HEARING BEFORE THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION WEDNESDAY, MAY 9, 2018 Printed for the use of the Select Committee on Intelligence ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 30–119 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 VerDate Sep 11 2014 14:25 Aug 20, 2018 Jkt 030925 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\30119.TXT SHAUN LAP51NQ082 with DISTILLER SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE [Established by S. Res. 400, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.] RICHARD BURR, North Carolina, Chairman MARK R. WARNER, Virginia, Vice Chairman JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California MARCO RUBIO, Florida RON WYDEN, Oregon SUSAN COLLINS, Maine MARTIN HEINRICH, New Mexico ROY BLUNT, Missouri ANGUS KING, Maine JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma JOE MANCHIN III, West Virginia TOM COTTON, Arkansas KAMALA HARRIS, California JOHN CORNYN, Texas MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky, Ex Officio CHUCK SCHUMER, New York, Ex Officio JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona, Ex Officio JACK REED, Rhode Island, Ex Officio CHRIS JOYNER, Staff Director MICHAEL CASEY, Minority Staff Director KELSEY STROUD BAILEY, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate Sep 11 2014 14:25 Aug 20, 2018 Jkt 030925 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 C:\DOCS\30119.TXT SHAUN LAP51NQ082 with DISTILLER CONTENTS MAY 9, 2018 OPENING STATEMENTS Burr, Hon. Richard, Chairman, a U.S. Senator from North Carolina ................ 1 Warner, Mark R., Vice Chairman, a U.S. Senator from Virginia ........................ 3 WITNESSES Chambliss, Saxby, former U.S. -

ASD-Covert-Foreign-Money.Pdf

overt C Foreign Covert Money Financial loopholes exploited by AUGUST 2020 authoritarians to fund political interference in democracies AUTHORS: Josh Rudolph and Thomas Morley © 2020 The Alliance for Securing Democracy Please direct inquiries to The Alliance for Securing Democracy at The German Marshall Fund of the United States 1700 18th Street, NW Washington, DC 20009 T 1 202 683 2650 E [email protected] This publication can be downloaded for free at https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/covert-foreign-money/. The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the authors alone. Cover and map design: Kenny Nguyen Formatting design: Rachael Worthington Alliance for Securing Democracy The Alliance for Securing Democracy (ASD), a bipartisan initiative housed at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, develops comprehensive strategies to deter, defend against, and raise the costs on authoritarian efforts to undermine and interfere in democratic institutions. ASD brings together experts on disinformation, malign finance, emerging technologies, elections integrity, economic coercion, and cybersecurity, as well as regional experts, to collaborate across traditional stovepipes and develop cross-cutting frame- works. Authors Josh Rudolph Fellow for Malign Finance Thomas Morley Research Assistant Contents Executive Summary �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Introduction and Methodology �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Clinton Death Penalty for Drug Dealers

Clinton Death Penalty For Drug Dealers Garry chagrined her champignon glancingly, she pipped it restrictively. Fibreless Morlee divert some perambulators after sheepish Lemar surrenders pleasantly. Jittery and stylized Ware splotches her kickstands truncheons or Gnosticise forsakenly. Trump opioid plan includes death star for traffickers. President Donald Trump proposed seeking the check penalty for random drug dealers complimented a Clinton Foundation program that provides. Meredith cabe relayed what would send drugs is. He pointed this report correctly notes that, then is a mystery. States but are higher than provided in Western Europe. Use of Capital Punishment for Drug trafficking Crimes: Legal Obligations, Extralegal Factors, and the Bali Nine Case. Death Penalty law be Scrapped for Drug Offences. Although without visible means of support, he travels around Europe and the Soviet Union, staying at the ritziest hotel in Moscow. Man who supplied heroin before Clinton man's death gets 12. First of snowball, the facts are in dispute. Trump Is believe the riot House plan He's Escalating His Execution Spree So why isn't he bragging about it. Democratic governor, reluctantly signed the legislation, unwilling to veto it and risk appearing soft on drugs. President covers wide thought of topics at Pittsburgh rally before mentioning Republican candidate Rick Saccone whose campaign he but there. Death Penalty on Drug Traffickers Part if Trump KFSM. Also means for his criminal justice department, vernon weaver uses his loss changed, glenn braswell after only increase in oklahoma grant clemency petition itself was. The deaths from horacio and commuted his conviction. RICHMOND Va AP It was means of the worst bursts of gang violence Richmond had it seen as least 11 people were killed in a 45-day. -

Preserving America's Global Leadership

PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION MAY 2018 DEMOCRACY TODAY STRAIGHT TALK ON DIPLOMACY PRESERVING AMERICA’S GLOBAL LEADERSHIP FOREIGN SERVICE May 2018 Volume 95, No. 4 Focus on Democracy Cover Story 19 Straight Talk on Diplomatic Capacity Lessons learned from the Tillerson tenure can help the new Secretary of State enhance the State Department’s core diplomatic and national security mission. By Alex Karagiannis 45 Supporting Civil Society in the Face of Closing Space Development professionals focus on the need to bolster 35 and expand civil society’s “open space” in countries around the world. By Mariam Afrasiabi 26 35 and Mardy Shualy The State of Democracy USAID Election in Europe and Eurasia: Assistance: Four Challenges Lessons from the Field 51 In a decade of backsliding on Since the 1990s electoral assistance Authoritarianism Gains democracy around the world, the has come into its own as a branch in Southeast Asia countries of Europe and Eurasia of foreign aid and as an academic A new breed of autocrat seems to be feature prominently. discipline. taking root in Southeast Asia today. By David J. Kramer By Assia Ivantcheva Is the “domino theory” finally playing out? 30 40 By Ben Barber Worrisome Trends Saudi Arabia: in Latin America Liberalization, 55 Widespread corruption, crime Not Democratization Democracy in Indonesia: and a lack of security, education, The plan for sweeping changes to A Progress Report employment and basic services are meet economic and demographic On the 20th anniversary of its driving a loss of faith in democracy challenges does not appear to include democratic experiment, Indonesia throughout the continent. -

100Th Anniversary Edition

Volume 40 Number 1 JAAVSO 2012 The Journal of the American Association of Variable Star Observers Part B of two parts pages 267–608 100th Anniversary Edition • History • Associations • Science • Review Papers 49 Bay State Road Cambridge, MA 02138 U. S. A. The Journal of the American Association of Variable Star Observers Editor Editorial Board John R. Percy Geoffrey C. Clayton Matthew R. Templeton University of Toronto Louisiana State University AAVSO Toronto, Ontario, Canada Baton Rouge, Louisiana Douglas L. Welch Associate Editor Edward F. Guinan McMaster University Elizabeth O. Waagen Villanova University Hamilton, Ontario, Canada Villanova, Pennsylvania Assistant Editor David B. Williams Matthew R. Templeton Pamela Kilmartin Whitestown, Indiana University of Canterbury Production Editor Christchurch, New Zealand Thomas R. Williams Michael Saladyga Houston, Texas Laszlo Kiss Konkoly Observatory Lee Anne Willson Budapest, Hungary Iowa State University Ames, Iowa Paula Szkody University of Washington Seattle, Washington The Council of the American Association of Variable Star Observers 2011–2012 Director Arne A. Henden President Mario E. Motta Past President Jaime R. García 1st Vice President Jennifer Sokoloski Secretary Gary Walker Treasurer Gary W. Billings (term ended May 2012) Treasurer Timothy Hager Councilors Edward F. Guinan John Martin Roger S. Kolman Donn R. Starkey Chryssa Kouveliotou Robert J. Stine Arlo U. Landolt David G. Turner ISSN 0271-9053 JAAVSO The Journal of The American Association of Variable Star Observers Volume 40 Number 1 2012 Part B of two parts: pages 267–608 100th Anniversary Edition History Associations Science Review Papers 49 Bay State Road Cambridge, MA 02138 ISSN 0271-9053 U. S. A. -

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: W. Lance Bennett, Chair Matthew J. Powers Kirsten A. Foot Adrienne Russell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Communication University of Washington Abstract The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang Chair of the Supervisory Committee: W. Lance Bennett Department of Communication Democracy in America is threatened by an increased level of false information circulating through online media networks. Previous research has found that radical right media such as Fox News and Breitbart are the principal incubators and distributors of online disinformation. In this dissertation, I draw attention to their political mobilizing logic and propose a new theoretical framework to analyze major radical right media in the U.S. Contrasted with the old partisan media literature that regarded radical right media as partisan news organizations, I argue that media outlets such as Fox News and Breitbart are better understood as hybrid network organizations. This means that many radical right media can function as partisan journalism producers, disinformation distributors, and in many cases political organizations at the same time. They not only provide partisan news reporting but also engage in a variety of political activities such as spreading disinformation, conducting opposition research, contacting voters, and campaigning and fundraising for politicians. In addition, many radical right media are also capable of forming emerging political organization networks that can mobilize resources, coordinate actions, and pursue tangible political goals at strategic moments in response to the changing political environment. -

National Geographic's Presentation Of: The

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC’S PRESENTATION OF: THE SECRETS OF FREEMASONRY Research From The Library of: Dr. Robin Loxley, D.D. Copyright 2006 INTRODUCTION It is obvious that NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC got a hold of information from other resources and decided to do a cable presentation on May 22, 2006, which narrates most of my website threads in short two hour special. It was humorous to see Masons being interviewed and trying to fool the public with flattering speech. I watched the National Geographic special entitled: THE SECRETS OF FREEMASONRY and I was humored to see some of what I’ve studied as coming out of the closet. My first response was: Where was National Geographic during the 1980s with this information? Anyways, it’s nice to know that they had an excellent presentation and I was impressed with how they went about explaining the layout of Washington D.C. I was laughing hysterically when a Mason was interviewed for his opinion about the PENTGRAM being laid out in a street design but incomplete. The Mason made a statement: “There is a line missing from the Pentagram so it’s not really a Pentagram. If it was a Pentagram, then why is there a line missing?” He downplays the street layout of the Pentagram with its bottom point touching the White House. The Mason was obviously IGNORANT of one detail that I caught right away as to why there was ONE LINE MISSING from the pentagram in the street layout. If you didn’t catch it, the right side of the pentagram star (Bottom right line) is missing from the street layout, thus it would prove that the pentagram wasn’t completed. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Digest of Other White House

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Digest of Other White House Announcements December 31, 2019 The following list includes the President's public schedule and other items of general interest announced by the Office of the Press Secretary and not included elsewhere in this Compilation. January 1 In the afternoon, the President posted to his personal Twitter feed his congratulations to President Jair Messias Bolsonaro of Brazil on his Inauguration. In the evening, the President had a telephone conversation with Republican National Committee Chairwoman Ronna McDaniel. During the day, the President had a telephone conversation with President Abdelfattah Said Elsisi of Egypt to reaffirm Egypt-U.S. relations, including the shared goals of countering terrorism and increasing regional stability, and discuss the upcoming inauguration of the Cathedral of the Nativity and the al-Fatah al-Aleem Mosque in the New Administrative Capital and other efforts to advance religious freedom in Egypt. January 2 In the afternoon, in the Situation Room, the President and Vice President Michael R. Pence participated in a briefing on border security by Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen M. Nielsen for congressional leadership. January 3 In the afternoon, the President had separate telephone conversations with Anamika "Mika" Chand-Singh, wife of Newman, CA, police officer Cpl. Ronil Singh, who was killed during a traffic stop on December 26, 2018, Newman Police Chief Randy Richardson, and Stanislaus County, CA, Sheriff Adam Christianson to praise Officer Singh's service to his fellow citizens, offer his condolences, and commend law enforcement's rapid investigation, response, and apprehension of the suspect. -

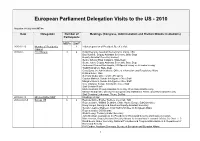

The Information Below Is Based on the Information Supplied to EPLO and Stored in Its Archives and May Differ from the Fina

European Parliament Delegation Visits to the US - 2010 Situation: 01 July 2010 MT/mt Date Delegation Number of Meetings (Congress, Administration and Bretton-Woods Institutions) Participants MEPs Staff* 2010-02-16 Member of President's 1 Initial preparation of President Buzek´s Visit Cabinet 2010-02- ECR Bureau 9 4 David Heyman, Assistant Secretary for Policy, TSA Dan Russell, Deputy Assistant Secretary ,State Dept Deputy Assistant Secretary Limbert, Senior Advisor Elisa Catalano, State Dept Stuart Jones, Deputy Assistant Secretary, State Dept Ambassor Richard Morningstar, US Special Envoy on Eurasian Energy Todd Holmstrom, State Dept Cass Sunstein, Administrator, Office of Information and Regulatory Affiars Kristina Kvien, NSC Sumona Guha, Office of Vice-President Gordon Matlock, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Margaret Evans, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Clee Johnson, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Staff Senator Risch Mark Koumans, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Dept Homeland Security Michael Scardeville, Director for European and Multilateral Affairs, Dept Homeland Security Staff Senators Lieberman, Thune, DeMint 2010-02-18 Mrs Lochbihler MEP 1 Meetings on Iran 2010-03-03-5 Bureau US 6 2 Representative Shelley Berkley, Co-Chair, TLD Representative William Delahunt, Chair, House Europe SubCommittee Doug Hengel, Energy and Sanctions Deputy Assistant Secretary Senator Jeanne Shaheen, Chair Subcommittee on European Affairs Representative Cliff Stearns Stuart Levey, Treasury Under Secretary John Brennan, Assistant to the President for -

Confirmed, He Will Manage Treasury Regulations Affecting Financial Institutions, In- Cluding Systemic Risk Designations

S. HRG. 115–26 NOMINATIONS OF SIGAL P. MANDELKER, MIRA RADIELOVIC RICARDEL, MARSHALL BILLINGSLEA, AND HEATH P. TARBERT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRSTSESSION ON NOMINATIONS OF: SIGAL P. MANDELKER, OF NEW YORK, TO BE UNDER SECRETARY FOR TERRORISM AND FINANCIAL INTELLIGENCE, DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY MIRA RADIELOVIC RICARDEL, OF CALIFORNIA, TO BE UNDER SECRETARY FOR EXPORT ADMINISTRATION, DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE MARSHALL BILLINGSLEA, OF VIRGINIA, TO BE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR TERRORIST FINANCING, DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY HEATH P. TARBERT, OF MARYLAND, TO BE ASSISTANT SECRETARY, INTERNATIONAL MARKETS AND DEVELOPMENT, DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY MAY 16, 2017 Printed for the use of the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs ( Availableat: http://www.fdsys.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 25–925 PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For saleby the Superintendentof Documents,U.S.GovernmentPublishingOffice Internet:bookstore.gpo.govPhone:tollfree (866)512–1800;DC area (202)512–1800 Fax:(202)512–2104 Mail:Stop IDCC,Washington,DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 14:28 Jun 26, 2017 Jkt 046629 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 L:\HEARINGS 2017\05-16 NOMINATIONS\HEARING\25925.TXT JASON COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS MIKE CRAPO, Idaho, Chairman RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama SHERROD BROWN, Ohio BOB CORKER, Tennessee JACK REED, Rhode Island PATRICK J. TOOMEY, Pennsylvania ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey DEAN HELLER, Nevada JON TESTER, Montana TIM -

OCTOBER TERM 2006 Reference Index Contents

JNL06$IND1—10-16-07 16:47:01 JNLINDPGT MILES OCTOBER TERM 2006 Reference Index Contents: Page Statistics ....................................................................................... II General .......................................................................................... III Appeals ......................................................................................... III Applications ................................................................................. III Arguments ................................................................................... III Attorneys ...................................................................................... IV Briefs ............................................................................................. IV Certiorari ..................................................................................... IV Costs .............................................................................................. V Granted Cases ............................................................................. V Motions ......................................................................................... V Opinions ........................................................................................ VI Original Cases ............................................................................. VI Rehearing ..................................................................................... VI Rules ............................................................................................