Douze Points for Peace the Eurovision Song Contest and Its Role in Processes of Transitional Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of Russia and Ukraine's Use of the Eurovision Song

Lund University FKVK02 Department of Political Science Spring 2020 Peace and Conflict Studies Supervisor: Fredrika Larsson The Battle of Eurovision A case study of Russia and Ukraine’s use of the Eurovision Song Contest as a cultural battlefield Character count: 59 832 Julia Orinius Welander Abstract This study aims to explore and analyze how Eurovision Song Contest functioned as an alternative – cultural – battlefield in the Russian-Ukrainian conflict over Crimea. With the use of soft power politics in warfare as the root of interest, this study uses the theories of cultural diplomacy and visual international relations to explore how images may be central to modern-day warfare and conflicts as the perception of. The study has a theory-building approach and aims to build on the concept of cultural diplomacy in order to explain how the images sent out by states can be politized and used to conduct cultural warfare. To explore how Russia and Ukraine used Eurovision Song Contest as a cultural battlefield this study uses the methodological framework of a qualitative case study with the empirical data being Ukraine’s and Russia’s Eurovision Song Contest performances in 2016 and 2017, respectively, which was analyzed using Roland Barthes’ method of image analysis. The main finding of the study was that both Russia and Ukraine used ESC as a cultural battlefield on which they used their performances to alter the perception of themselves and the other by instrumentalizing culture for political gain. Keywords: cultural diplomacy, visual IR, Eurovision Song Contest, Crimea Word count: 9 732 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................ -

90 Av 100 Ålänningar Sågar Upphöjd Korsning Säger Nej

Steker crépe på Lilla holmen NYHETER. Fransmannen Zed Ziani har fl yttat sitt créperie till Lilla holmen i Mariehamn och för första gången på många år fi nns det servering igen på friluftsområdet. Både salta och söta crépe, baguetter och kaffe fi nns på menyn i det lilla caféet med utsikt över fågeldammen Lördag€ SIDAN 18 12 MAJ 2007 NR 100 PRIS 1,20 och Slemmern. 90 av 100 ålänningar sågar upphöjd korsning Säger nej. Annette Gammals deltog i Nyans gatupejling om Ålandsvägens upphöjda korsning- ar. Men planerarna har politikernas uppdrag att se Men frågan är: Vems bekvämlighet är viktigast? till också den lätta trafi kens intressen. NYHETER. Ska alla trafi kanter – bilister, – Jag tycker mig känna igen trafi kplane- ålänningarna kanske har svårare än andra att – Jag hatar bumpers, sa Ingmar Håkansson cyklister, fotgängare och gamla med rullator ringsdiskussionen från 1960-talet när devisen ge avkall på bilbekvämligheten. från Lumparland som har jobbat 26 år som – behandlas jämlikt i stadstrafi ken? var att bilarna ska fram, allt ska ske på bilis- – Åland är väldigt bilberoende. Men man yrkeschaufför. Ja, säger planerarna i Mariehamn. Politi- ternas villkor och de oskyddade och sårbara måste ändå tänka på att också andra har rätt 90 personer svarade nej på frågan om de vill kerna har godkänt de styrdokument som de trafi kanterna får klara sig bäst de kan, säger till en säker trafi kmiljö. ha upphöjda korsningar, tio svarade ja. baserar ombyggnaden av Ålandsvägen på. tekniska nämndens ordförande Folke Sjö- Känslorna var starka då Nyan i går pejlade – Jag har barn som skall gå över Ålandsvä- Det som nu har hänt är att en del politiker lund. -

WEE19 – Reviewed by London Student

West End Eurovision 2019: A Reminder of the Talent and Supportive Community in the Theatre Industry ARTS, THEATRE Who doesn’t love Eurovision? The complete lack of expectation for any UK contestant adds a laissez faire tone to the event that works indescribably well with the zaniness of individual performances. Want dancing old ladies? Look up Russia’s 2012 entrance. Has the chicken dance from primary school never quite left your consciousness? Israel in 2018 had you covered. Eurovision is camp and fun, and we need more of that these days… cue West End Eurovision, a charity event where the casts from different shows compete with previous Eurovision songs to win the approval of a group of judges and the audience. The seven shows competing were: Only Fools and Horses, Everybody’s Talking About Jamie, Aladdin, Mamma Mia!, Follies, The Phantom of the Opera, and Wicked. Each cast performed for four judges – Amber Davies, Bonnie Langford, Wayne Sleep, and Tim Vincent – following a short ident. Quite what these were for I’m not sure was explained properly to the cast: are they adverts for their shows (Everybody’s Talking About Jamie), adverts for the song they’re to perform (Phantom) or adverts for Eurovision generally (Mamma Mia!)? I don’t know, but they were all amusing and a good way to introduce each act. The cast of Only Fools and Horses opened the show, though they unfortunately came last in the competition, a less-than jubly result. That said, with sparkling costumes designed by Lisa Bridge, the performance of ‘Dancing Lasha Tumbai’, first performed by Ukraine in 2007, was certainly in the spirit of Eurovision and made for a sound opening number. -

The Grave Goods of Roman Hierapolis

THE GRAVE GOODS OF ROMAN HIERAPOLIS AN ANALYSIS OF THE FINDS FROM FOUR MULTIPLE BURIAL TOMBS Hallvard Indgjerd Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History University of Oslo This thesis is submitted for the degree of Master of Arts June 2014 The Grave Goods of Roman Hierapolis ABSTRACT The Hellenistic and Roman city of Hierapolis in Phrygia, South-Western Asia Minor, boasts one of the largest necropoleis known from the Roman world. While the grave monuments have seen long-lasting interest, few funerary contexts have been subject to excavation and publication. The present study analyses the artefact finds from four tombs, investigating the context of grave gifts and funerary practices with focus on the Roman imperial period. It considers to what extent the finds influence and reflect varying identities of Hierapolitan individuals over time. Combined, the tombs use cover more than 1500 years, paralleling the life-span of the city itself. Although the material is far too small to give a conclusive view of funerary assem- blages in Hierapolis, the attempted close study and contextual integration of the objects does yield some results with implications for further studies of funerary contexts on the site and in the wider region. The use of standard grave goods items, such as unguentaria, lamps and coins, is found to peak in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. Clay unguentaria were used alongside glass ones more than a century longer than what is usually seen outside of Asia Minor, and this period saw the development of new forms, partially resembling Hellenistic types. Some burials did not include any grave gifts, and none were extraordinarily rich, pointing towards a standardised, minimalistic set of funerary objects. -

Dschinghis Khan HISTORY MIT RS V04 MIT BILDERN

DIE GESCHICHTE DER POPGRUPPE DSCHINGHIS KHAN Mit Ihren Hits wie Dschinghis Khan – Moskau – Hadschi Halef Omar – Rocking Son of Dschinghis Khan – Pistolero - Mexiko und vielen, vielen mehr eroberte die deutschsprachige Popgruppe Dschinghis Khan als THE CONQUEROR IN MUSIC bis heute die Welt. Alles begann 1979. Der Komponist und Produzent, Ralph Siegel, und der Textdichter, Dr. Bernd Meinunger , schrieben das Lied DSCHINGHIS KHAN, mit welchem die gleichnamige Gruppe DSCHINGHIS KHAN zum Vorentscheid des Deutschen Beitrags für den EUROVISION SONG CONTES T – EIN LIED FÜR ISRAEL – am 17. März 1979 in der Rudi – Sedlma yer in München antratt. Dschinghis Khan, das waren die Künstler Wolfgang Heichel, Steve Bender, Edina Pop, Henriette Strobel, Leslie Mandoki und der talentierte Tänzer Louis Potgieter. Innerhalb von nur 6 Wochen, also unter immensem Zeitdruck und mit hohem finanziellem Aufwand, wurden im Siegel Studio die Plattenproduktion der ersten Single – Dschinghis Khan und Sahara – produziert. Vom angesagten Kostümdesigner , Marc Manó, die exot ischen Kostüme geschneidert; von der international arbeitenden Visagisten, Heidi Moser , die markanten Make ups gestaltet; vom Choreographie-Profi für Fernsehshows , Hannes Winkler, wurde die tänzerische Bühnenshow entwickelt und die Künstler von Dschinghis Khan waren je den Tag im Studio und probten, probten und probten, solange, bis die Bühnenshow perfekt war. Dann kam der große Tag. Am 17. März 1979 war in der Rudi-Sedlmayr-Halle in München die Premiere. Die Popgruppe Dschinghis Khan nahm mit ihrem gleichnamigen Titel „ Dschinghis Khan“ an der Deutschen Vorentscheidung zum EUROVISION SONG CONTEST – EIN LIED FÜR ISRAEL - teil. Drei Minuten hatte Dschinghis Khan Zeit , dem deutschen Fernsehpublikum und den Juroren zu zeigen, das s sie den besten Beitrag präsentieren würden. -

Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018

The 100% Unofficial Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018 O Guia Rápido 100% Não-Oficial do Eurovision Song Contest 2018 for Commentators Broadcasters Media & Fans Compiled by Lisa-Jayne Lewis & Samantha Ross Compilado por Lisa-Jayne Lewis e Samantha Ross with Eleanor Chalkley & Rachel Humphrey 2018 Host City: Lisbon Since the Neolithic period, people have been making their homes where the Tagus meets the Atlantic. The sheltered harbour conditions have made Lisbon a major port for two millennia, and as a result of the maritime exploits of the Age of Discoveries Lisbon became the centre of an imperial Portugal. Modern Lisbon is a diverse, exciting, creative city where the ancient and modern mix, and adventure hides around every corner. 2018 Venue: The Altice Arena Sitting like a beautiful UFO on the banks of the River Tagus, the Altice Arena has hosted events as diverse as technology forum Web Summit, the 2002 World Fencing Championships and Kylie Minogue’s Portuguese debut concert. With a maximum capacity of 20000 people and an innovative wooden internal structure intended to invoke the form of Portuguese carrack, the arena was constructed specially for Expo ‘98 and very well served by the Lisbon public transport system. 2018 Hosts: Sílvia Alberto, Filomena Cautela, Catarina Furtado, Daniela Ruah Sílvia Alberto is a graduate of both Lisbon Film and Theatre School and RTP’s Clube Disney. She has hosted Portugal’s edition of Dancing With The Stars and since 2008 has been the face of Festival da Cançao. Filomena Cautela is the funniest person on Portuguese TV. -

DEUTSCHE KARAOKE LIEDER 2Raumwohnung 36 Grad DUI-7001

DEUTSCHE KARAOKE LIEDER 2Raumwohnung 36 Grad DUI-7001 Adel Tawil Ist Da Jemand DUI-7137 Amigos 110 Karat DUI-7166 Andrea Berg Das Gefuhl DUI-7111 Andrea Berg Davon Geht Mein Herz Nicht Unter DUI-7196 Andrea Berg Du Bist Das Feuer DUI-7116 Andrea Berg Du Hast Mich 1000 Mal Belogen DUI-7004 Andrea Berg Feuervogel DUI-7138 Andrea Berg Himmel Auf Erden DUI-7112 Andrea Berg In Dieser Nacht DUI-7003 Andrea Berg Lass Mich In Flammen Stehen DUI-7117 Andrea Berg Lust Auf Pures Leben DUI-7118 Andrea Berg Mosaik DUI-7197 Andrea Berg Wenn Du Jetzt Gehst, Nimm Auch Deine Liebe Mit DUI-7002 Andreas Gabalier I Sing A Liad Für Di DUI-7054 Andreas MarWn Du Bist Alles (Maria Maria) DUI-7139 Anna-Maria Zimmermann Du Hast Mir So Den Kopf Verdreht DUI-7119 Anna-Maria Zimmermann Scheiß Egal DUI-7167 Anstandslos & Durchgeknallt Egal DUI-7168 Beatrice Egli Fliegen DUI-7120 Beatrice Egli Keiner Küsst Mich (So Wie Du) DUI-7175 Beatrice Egli Mein Ein Und Alles DUI-7176 Beatrice Egli Was Geht Ab DUI-7177 Bill Ramsey Ohne Krimi Geht Die Mimi Nie Ins Bea DUI-7063 Cassandra Steen & Adel Tawil Stadt DUI-7055 Charly Brunner Wahre Liebe DUI-7178 Chris Roberts Du Kannst Nicht Immer 17 Sein DUI-7005 Chris Roberts Ich Bin Verliebt In Die Liebe DUI-7134 ChrisWan Anders Einsamkeit Had Viele Namen DUI-7006 ChrisWna Sturmer Engel Fliegen Einsam DUI-7007 ChrisWna Stürmer Mama Ana Ahabak DUI-7008 Cindy & Bert Immer Wieder Sonntags DUI-7136 Claudia Jung Mein Herz Lässt Dich Nie Allein DUI-7009 Conny & Peter Alexander Verliebt Verlobt Verheiratet DUI-7010 Conny Francis Schöner Fremder -

Plays by Women on Female Writers and Literary Characters a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of So

MYTHMAKING IN PROGRESS: PLAYS BY WOMEN ON FEMALE WRITERS AND LITERARY CHARACTERS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY PÜRNUR UÇAR-ÖZB İRİNC İ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH LITERATURE OCTOBER, 2007 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences ____________________________ Prof. Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________________ Prof. Dr. Wolf König Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Nursel İçöz Prof. Dr. Meral Çileli Co-Supervisor Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Ay şegül Yüksel (Ankara Uni.) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ünal Norman (METU) Asst. Prof. Dr. Nurten Birlik (METU) Dr. Rüçhan Kayalar (Bilkent Uni.) ii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last Name: Pürnur Uçar-Özbirinci Signature: iii ABSTRACT MYTHMAKING IN PROGRESS: PLAYS BY WOMEN ON FEMALE WRITERS AND LITERARY CHARACTERS Uçar-Özbirinci, Pürnur Ph.D., English Literature Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Meral Çileli Co-Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Nursel İçöz October 2007, 247 pages This thesis analyzes the process of women’s mythmaking in the plays written by female playwrights. -

Lesbian Camp 02/07

SQS Bespectacular and over the top. On the genealogy of lesbian camp 02/07 Annamari Vänskä 66 In May 2007, the foundations of the queer Eurovision world seemed to shake once again as Serbia’s representative, Queer Mirror: Perspectives Marija Šerifović inspired people all over Europe vote for her and her song “Molitva”, “Prayer”. The song was praised, the singer, daughter of a famous Serbian singer, was hailed, and the whole song contest was by many seen in a new light: removed from its flamboyantly campy gay aesthetics which seems to have become one of the main signifiers of the whole contest in recent decades. As the contest had al- ready lost the Danish drag performer DQ in the semi finals, the victory of Serbia’s subtle hymn-like invocation placed the whole contest in a much more serious ballpark. With “Molitva” the contest seemed to shrug off its prominent gay appeal restoring the contest to its roots, to the idea of a Grand Prix of European Song, where the aim has been Marija Šerifović’s performance was said to lack camp and restore the to find the best European pop song in a contest between contest to its roots, to the idea of a Grand Prix of European Song. different European nations. The serious singer posed in masculine attire: tuxedo, white riosity was appeased: not only was Šerifović identified as shirt, loosely hanging bow tie and white sneakers, and was a lesbian but also as a Romany person.1 Šerifović seemed surrounded by a chorus of five femininely coded women. -

Through the Iris TH Wasteland SC Because the Night MM PS SC

10 Years 18 Days Through The Iris TH Saving Abel CB Wasteland SC 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10,000 Maniacs 1,2,3 Redlight SC Because The Night MM PS Simon Says DK SF SC 1975 Candy Everybody Wants DK Chocolate SF Like The Weather MM City MR More Than This MM PH Robbers SF SC 1975, The These Are The Days PI Chocolate MR Trouble Me SC 2 Chainz And Drake 100 Proof Aged In Soul No Lie (Clean) SB Somebody's Been Sleeping SC 2 Evisa 10CC Oh La La La SF Don't Turn Me Away G0 2 Live Crew Dreadlock Holiday KD SF ZM Do Wah Diddy SC Feel The Love G0 Me So Horny SC Food For Thought G0 We Want Some Pussy SC Good Morning Judge G0 2 Pac And Eminem I'm Mandy SF One Day At A Time PH I'm Not In Love DK EK 2 Pac And Eric Will MM SC Do For Love MM SF 2 Play, Thomas Jules And Jucxi D Life Is A Minestrone G0 Careless Whisper MR One Two Five G0 2 Unlimited People In Love G0 No Limits SF Rubber Bullets SF 20 Fingers Silly Love G0 Short Dick Man SC TU Things We Do For Love SC 21St Century Girls Things We Do For Love, The SF ZM 21St Century Girls SF Woman In Love G0 2Pac 112 California Love MM SF Come See Me SC California Love (Original Version) SC Cupid DI Changes SC Dance With Me CB SC Dear Mama DK SF It's Over Now DI SC How Do You Want It MM Only You SC I Get Around AX Peaches And Cream PH SC So Many Tears SB SG Thugz Mansion PH SC Right Here For You PH Until The End Of Time SC U Already Know SC Until The End Of Time (Radio Version) SC 112 And Ludacris 2PAC And Notorious B.I.G. -

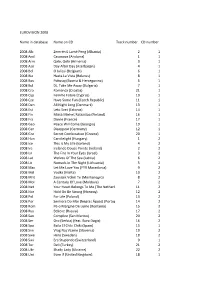

EUROVISION 2008 Name in Database Name on CD Track Number CD

EUROVISION 2008 Name in database Name on CD Track number CD number 2008 Alb Zemrën E Lamë Peng (Albania) 2 1 2008 And Casanova (Andorra) 1 1 2008 Arm Qele, Qele (Armenia) 3 1 2008 Aze Day After Day (Azerbaijan) 4 1 2008 Bel O Julissi (Belgium) 6 1 2008 Bie Hasta La Vista (Belarus) 8 1 2008 Bos Pokusaj (Bosnia & Herzegovina) 5 1 2008 Bul DJ, Take Me Away (Bulgaria) 7 1 2008 Cro Romanca (Croatia) 21 1 2008 Cyp Femme Fatale (Cyprus) 10 1 2008 Cze Have Some Fun (Czech Republic) 11 1 2008 Den All Night Long (Denmark) 13 1 2008 Est Leto Svet (Estonia) 14 1 2008 Fin Missä Miehet Ratsastaa (Finland) 16 1 2008 Fra Divine (France) 17 1 2008 Geo Peace Will Come (Georgia) 19 1 2008 Ger Disappear (Germany) 12 1 2008 Gre Secret Combination (Greece) 20 1 2008 Hun Candlelight (Hungary) 1 2 2008 Ice This Is My Life (Iceland) 4 2 2008 Ire Irelande Douze Pointe (Ireland) 2 2 2008 Isr The Fire In Your Eyes (Israel) 3 2 2008 Lat Wolves Of The Sea (Latvia) 6 2 2008 Lit Nomads In The Night (Lithuania) 5 2 2008 Mac Let Me Love You (FYR Macedonia) 9 2 2008 Mal Vodka (Malta) 10 2 2008 Mnt Zauvijek Volim Te (Montenegro) 8 2 2008 Mol A Century Of Love (Moldova) 7 2 2008 Net Your Heart Belongs To Me (The Netherlands) 11 2 2008 Nor Hold On Be Strong (Norway) 12 2 2008 Pol For Life (Poland) 13 2 2008 Por Senhora Do Mar (Negras Águas) (Portugal) 14 2 2008 Rom Pe-o Margine De Lume (Romania) 15 2 2008 Rus Believe (Russia) 17 2 2008 San Complice (San Marino) 20 2 2008 Ser Oro (Serbia) (feat. -

Lieu : Koncertna Dvorana Vatroslav Lisinski De Zagreb ( Yougoslavie )

Lieu : Koncertna Dvorana Vatroslav Orchestre : Orchestre de la JRT. Lisinski de Zagreb ( Yougoslavie ). Présentation : Helga Vlahovic & Oliver Date : Samedi 5 Mai. Mlakar. Réalisateur : Nenad Puhovski. Durée : 2h 49. Zagreb, capitale de la république Yougoslave de Croatie accueille le concours 1990, le groupe Riva, victorieux en 1989, étant originaire de cette partie du pays. La salle de concert Vatroslav Lisinski est pour l’occasion habillée de néons et offre au concours un décor beaucoup plus coloré et lumineux que les années précédentes. Le producteur a voulu un spectacle résolument plus jeune et plus enlevé que les dernières années et les chansons se succéderont sans l’intervention du couple de présentateurs, Helga Vlahovic et Oliver Mlakar. Ce rythme volontairement rapide permet au concours de réduire substantiellement sa durée, de plus de 20 minutes par rapport à 1989. Le concours a, cette année, une mascotte nommée Eurocat qui après une courte ballade musicale dans Zagreb amènera les téléspectateurs jusqu’à la salle. Il participera aux cartes postales qui annoncent chacun des candidats. Pour célébrer l’année européenne du tourisme, ces films ont été tournés dans chacun des pays participants. Les présentateurs se contenteront d’ouvrir le concours, Helga en anglais et Oliver en français, de faire une intervention entre les 7 ème et 8 ème chansons puis entre les 15 ème et 16 ème et bien sûr pour les votes. Marie-France Brière vient d’être nommée responsable de l’unité divertissements d’Antenne 2 et décide, à ce titre, de s’occuper seule du choix de la chanson française pour l’Eurovision.