Pope's Maestro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Association of Jewish Libraries N E W S L E T T E R February/March 2008 Volume XXVII, No

Association of Jewish Libraries N E W S L E T T E R February/March 2008 Volume XXVII, No. 3 JNUL Officially Becomes The National Library of Israel ELHANAN ADL E R On November 26, 2007, The Knesset enacted the “National Li- assistance of the Yad Hanadiv foundation, which previously brary Law,” transforming the Jewish National and University contributed the buildings of two other state bodies: the Knesset, Library (JNUL) at The Hebrew University’s Givat Ram campus and the Supreme Court. The new building will include expanded into the National Library of Israel. reading rooms and state-of-the-art storage facilities, as well as The JNUL was founded in 1892 by the Jerusalem Lodge of a planned Museum of the Book. B’nai B’rith. After the first World War, the library’s ownership The new formal status and the organizational change will was transferred to the World Zionist Organization. With the enable the National Library to expand and to serve as a leader opening of the Hebrew University on the Mount Scopus campus in its scope of activities in Israel, to broaden its links with simi- in 1925, the library was reorganized into the Jewish National and lar bodies in the world, and to increase its resources via the University Library and has been an administrative unit of the government and through contributions from Israel and abroad. Hebrew University ever since. With the founding of the State The law emphasizes the role of the Library in using technology of Israel the JNUL became the de facto national library of Israel. -

The Israel Philharmonic Orchestra

January 1987 Festive Events celebrating the Centenary of the birth of Arthur Rubinstein Under the Patronage of H.E. The President of Israel Series of 7 Concerts Zubin Mehta conductor Tel-Aviv, The Fredric R. Mann Auditorium The Israel Philharmonic Orchestra Founded in 1936 by Bronislaw Huberman Music Director : Zubin Mehta FESTIVE JUBILEE SEASON THE ISRAEL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA Founded in 1936 by Bronislaw Huberman • Music Director: Zubin Mehta The Fredric R. Mann Auditorium • P.O.Box 11292, 61112 Tel-Aviv; Telephone (03) 295092 The 51st Season / 1986-7 Festive Jubilee Season Festive Events celebrating the Centenary of the birth of Arthur Rubinstein Under the Patronage of H.E. The President of Israel, Mr. Chaim Herzog Series of 7 Concerts Zubin Mehta conductor Tel-Aviv, The Fredric R. Mann Auditorium January 1987 At 8.30 p.m. PUBLIC MANAGEMENT BOARD: Mr. D. Ben-Meir, Mr. A. Duizin Mr. Y. Ettinger, Mr. B. Gal-Ed, Mr. M.B. Gitter, Dr. A. Goldenberg, Mrs. A. Harris, Mr. P. Jacobi, Judge A.F. Landau (Chm'n), Mr. A. Levinsky, Mr. Z. Litwak*, Mr. Y. Mishori*, Mr. M. Neudorfer, Mr. Y. Oren, Mr. Y. Pasternak*, Mr. J. Pecker, Judge L.A. Rabinowitz, Mr. A. Shalev, Mr. N. Wolloch. (• IPO Management members) THE IPO FOUNDATION - Founding Members: Abba Eban (Chairman), David Blass, Yona Ettinger, Dr. Amnon Goldenberg, M.B. Gitter, Lewis Harris, Ernst Japhet, Y. Macht, Joseph Pecker, Raphael Recanati. Dr. Dapnna Schachner (Dir. Gen.) AMERICAN FRIENDS OF THE IPO: Zubin Mehta (Hon. Ch'mn); Fredric R. Mann (Pres.); Norman Bernstein, Itzhak Perlman (Vice Pres.); Susan B. -

Victor Stanislavsky Is Hailed As One of the Most Outstanding Young Israeli Pianists Today

Victor Stanislavsky is hailed as one of the most outstanding young Israeli pianists today. His international career has taken him to many countries in Europe, north and south America, China, South Korea and Australia. In the past concert season, he has given over 70 performances as a soloist, recitalist and a chamber musician to critical acclaim. As an avid chamber musician he has collaborated with such artists as violinists Christian Tetzlaff and David Garrett, cellist Gary Hoffman and Soprano Chen Reis. His major festival appearances include “Ravinia” (Chicago), “Meet in Beijing”, “Shanghai piano Festival” and the “Israel Festival”. Mr. Stanislavsky has performed in prestigious venues including Carnegie Hall and the 92Y in New-York, Chicago Arts Center, Bass performance hall in Fort Worth, Berlin Philharmonie, the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, St. Martin in the Fields Church in London, “Tsarytsino” Palace in Moscow, National Performing Arts Center in Beijing, Forbidden City concert hall in Beijing, Shanghai Conservatory, Qintai Grand Theater in Wuhan, Harbin Opera House and the Seoul Arts Center to name a few. In addition he regularly performs in all the major concert halls in Israel. He performed as a soloist with Milan’s Symphony Orchestra, China’s National Symphony Orchestra, China’s national Ballet Symphony Orchestra, KBS Symphony orchestra of South Korea and others as well as with leading orchestras in Israel collaborating with such conductors as Yoel Levi, Jose Maria Florencio, Kainen Johns, Li Xincao, Uri Segal, Gil Shohat and many others. Mr. Stanislavsky holds both bachelors and masters degrees summa cum laude, in music performance from the Buchmann-Mehta School of Music at Tel-Aviv University, where he studied with Mr. -

Review Tri-C Classical Piano Series: Daniel Gortler at CMA

Review Tri-C Classical Piano Series: Daniel Gortler at CMA (October 27) by Robert Rollin When Israeli pianist Daniel Gortler entered the stage for his Sunday afternoon recital at the Cleveland Art Museum’ s Gartner Auditorium, he radiated poise and concentration. Jet setter Gortler is on faculty at the Buchman-Mehta School of Music at Tel Aviv University and is guest piano studies pro- fessor at New York University’s Steinhardt School Depart- ment of Music. He regularly plays piano concertos and con- certizes in solo and chamber music recitals around the world. His program concentrated on the genre of piano fantasy and fantasia, and featured works by Mozart and Schumann. This was a clever choice because both composers are noted for their ability to string many themes together in a manner that makes their pieces seem structured and beautifully organized. Fantasiestücke, Op. 12,,1("6+!-%&&5+"$",1,'/*",!*,*("+,+/",!0- ,*%-+"$'&&,"'&+!" !,%'.%&,++%%'*"&,*",&'%($0,!& most. Gortler played the relatively slow Evening,,!6*+,("/",! '* '-++"& "& tone that made the oddly-grouped cross rhythms stand out. He also stressed dovetailed +'(*&'&++$"&+/!&((*'(*",0(*++"& ,!++&'!-%&&5+*,!* limited dynamic markings. He tossed off the dashing, quicksilver Soaring/",!('/*&6&$&!,,!, imitative lines between the two hands stood out from the rest of the music did not stop him from highlighting a growling low register passage when needed. The slow and deli- cate Why was lovely, as Gortler emphasized crystalline grace notes and other dramatic '&,*+,+$+'#(,,!"&,*%",,&,',," !,!&+"0,&,!(,,*&*"+(& lively. Whims,*("&(*""'-+0,&%'.%&,/",!$,*&,"& ,!%+&"& &"'-+ modal harmonies, was absolutely breathtaking. In the Night, marked appassionato, was $+'+,& '*,$**'- !,'-,.*1&,&1&%"!& 0(*++".$1 ,* inserting a slower and more delicate theme, he faithfully followed Schumann’s “faster and faster” marking to a rousing conclusion. -

Mark Morris Dance Group Thursday Though Saturday, September 22–24 Thursday Through Saturday, September 29, 30, October 1 Zellerbach Hall

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS Mark Morris Dance Group Thursday though Saturday, September 22–24 Thursday through Saturday, September 29, 30, October 1 Zellerbach Hall Craig Biesecker Joe Bowie Charlton Boyd Amber Darragh Rita Donahue Lorena Egan* Marjorie Folkman Lauren Grant John Heginbotham David Leventhal Bradon McDonald Gregory Nuber Maile Okamura June Omura Noah Vinson Julie Worden Michelle Yard Artistic Director Mark Morris Executive Director Nancy Umanoff MMDG Music Ensemble Members of the Berkeley Symphony Orchestra American Bach Soloists *apprentice Altria Group, Inc. is the Premiere Sponsor of the Mark Morris Dance Group’s 25th Anniversary Season. MetLife Foundation is the official sponsor of the Mark Morris Dance Group’s 25th Anniversary National Tour. Major support for the Mark Morris Dance Group is provided by Carnegie Corporation of New York, MetLife Foundation, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, The Shubert Foundation and Target. The Mark Morris Dance Group New Works Fund is supported by The Howard Gilman Foundation, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation. The Mark Morris Dance Group’s education and performance activities are supported by Independence Community Foundation. The Mark Morris Dance Group’s performances are made possible with public funds from the National Endowment for the Arts Dance Program and the New York State Council on the Arts, a State Agency. This presentation is made possible, in part, by Bank of America. Additional support is provided by an award from the National -

Salon Brochure

Charlotte White’s 2019/20 MEMBERSHIP INFORMATION Celebrating Our 31st Season OPENING GALA AWARDS CONCERT Wednesday, September 25, 2019 | 7 PM Kosciuszko Foundation 15 East 65th Street, New York, NY Dear Friends, Welcome to the 31st Season of the Salon de Virtuosi! We are delighted to continue the legacy of our founder Charlotte White by offering a series of unforgettable concerts featuring the most talented young musicians from around the world in intimate 19th Century salon settings throughout New York City, where you will have the opportunity to hear and get to know exceptional young artists who are destined to become our future “greats.” We celebrate the start of the season with our acclaimed Gala Awards Concert on September 25, 2019 at the elegant Kosciuszko Foundation, where we will present five of our2019 Career Grant Winners in a special concert hosted by the renowned musicologist and longtime Salon de Virtuosi friend Robert Sherman of WQXR. Other highlights of the Fall season include our Autumn in New York Concert on November 6, 2019 at the Liederkranz Foundation, presenting a talented young American pianist/ composer and a rising young American violinist, with a special guest appearance by 2017 Salon Career Grant Winner Asi Matathias. Our Holiday Concert on December 12, 2019 at the beautiful home of Elizabeth and Lewis Bryden at Hotel des Artistes will feature a phenomenal 16-year old violinist and an exciting American clarinetist. In the Spring we will continue our unique collaboration with the Consulates of Hungary and India and will also present a concert at the Consulate General of France, each featuring remarkable young talents. -

What's on in Tel Aviv /April

WHAT'S ON IN TEL AVIV / APRIL MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 1 2 MOSCOW CIRCUS SUDESH BHOSLE THE ON YOUR WAY APR 1-29 ORIGINAL VOICE OF Sportek,Hayarkon Park AMITABH (INDIA) 8:30 PM MAMOOTOT Bronfman Auditorium HOME VISIT BATSHEVA DANCE COMPANY: THE YOUNG DORIC STRING QUARTET ENSEMBLE CLASSIC MUSIC CONCERT 7 PM Mozart, Brahms, Britten Suzanne Dellal Center 8:30 PM Israel Conservatory for Music Warning: Excessive consumption of alcohol is dangerous and harmful to your health! Sale of alcoholic beverages is restricted to ages 18 and above 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 LA GAZZETTA THE ART OF BANKSY LIFE RUN WOVEN AND UNTANGLED BILLY ELLIOT DANIEL GORTLER FOREVER YOUNG - ROYAL OPERA OF STREET ART EXHIBITION WOMAN RACE NEW VIDEO WORKS IN THE MUSICAL PIANO RECITAL BOB DYLAN AT 75 WALLONIE FROM LIEGE APR 4-14 2 PM, Tel Aviv Port MUSEUM COLLECTION 2:30 PM Bach, Berg, Brahms ONGOING EXHIBITION APR 3-8 Herzliya Arena ONGOING FROM APR 6 Cinema City, 9 PM Museum of the Tel Aviv Performing Arts ISRAEL CALLING 2017 Helena Rubinstein Pavilion for Glilot Interchange Israel Conservatory of Music Jewish People Center GALA NIGHT EUROVISION Contemporary Art (Beit Hatfutsot) JERUSALEM BALLET LIVE EVENT SARONA TOUR FROM OLD TEL AVIV TO THE 8 PM Theatre Club, Every Friday, 11 AM “WHITE CITY” TOUR Jaffa Meeting point: Sarona Visitors’ Every Saturday, 11 AM Givataim Theater Center (11 Avraham Albert Meeting point: 46 Rothschild Mendler St.) Blvd. 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 ALUMINUM DON QUIXOTE TETRIS GAME ON CITY DESIGNERS’ MARKET AND WEST SIDE STORY INTERACTIVE SHOW FOR RUSSIAN BALLET THEATRE HALL BUILDING FOOD MARKET MUSICAL WITH ENGLISH THE ENTIRE FAMILY FROM ST. -

Israeli-American Pianist Daniel Gortler and Brazilian Violinist Daniel Guedes in Concert at the Jewish Museum May 16

Israeli-American Pianist Daniel Gortler and Brazilian Violinist Daniel Guedes In Concert at the Jewish Museum May 16 New York, NY, April 23, 2019 – The Jewish Museum will present Israeli-American pianist Daniel Gortler and Brazilian violinist Daniel Guedes performing the music of Ludwig van Beethoven, Edvard Grieg, and contemporary Brazilian composer Mozart Camargo Guarnieri on Thursday, May 16 at 8 pm. This is Mr. Gortler’s fifth appearance at the Jewish Museum, and Mr. Guedes’s first. The concert program features Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No. 9, Op. 47 (“Kreutzer Sonata”); Mozart Camargo Guarnieri’s Canção Sertaneja and Canto No. 1; a selection from Edvard Grieg’s Lyric Pieces; and Grieg’s Violin Sonata No. 3 in C minor, Op. 45. Tickets for the May 16 concert are $24 general; $16 students and seniors; and $12 Jewish Museum members. Further program and ticket information is available online at TheJewishMuseum.org/calendar or by calling 212.423.3337. The Jewish Museum is located at Fifth Avenue and 92nd Street, Manhattan. The recital program will include: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Violin Sonata No. 9, Op. 47 (“Kreutzer Sonata”) (35 min.) Published 1805 Adagio sostenuto – Presto Andante con variazioni Presto This sonata for piano and violin is notable for its technical difficulty, unusual length, and emotional scope. It is commonly known as the “Kreutzer Sonata” after violinist Rodolphe Kreutzer, to whom it was dedicated even though he disliked the piece and refused to play it. Violin Sonata No. 9 stands as one of the pillars in the repertoire written for violin and piano, and one of the best known works by Beethoven. -

Edição Comemorativa Revista Concerto 11 Anos Entrevista Jocy De Oliveira Nossos Músicos Homero Velho Temporadas Internacionai

ROTEIRO COMPLETO LANÇAMENTOS DE CDs E DVDs NOTÍCIAS MUSICAIS CONCERTOCONCERTOGUIA MENSAL DE MÚSICA ERUDITA R$ 7,00 SETEMBRO 2006 EDIÇÃO COMEMORATIVA REVISTA CONCERTO 11 ANOS ENTREVISTA JOCY DE OLIVEIRA NOSSOS MÚSICOS HOMERO VELHO TEMPORADAS INTERNACIONAIS PIANISTA CHINÊS VENCE CONCURSO VILLA-LOBOS BANDA SINFÔNICA ESTRÉIA ÓPERA DE RONALDO MIRANDA ATRÁS DA PAUTA JÚLIO MEDAGLIA SÃO PAULO, ANO XII, Nº 121 ISSN 1413-2052 ANO XII, Nº 121 SÃO PAULO, capa0906.p65 1 21/8/2006, 11:18 Lançamento 2006 Cds à venda na segunda quinzena de setembro nas lojas da Livraria Cultura e Loja Clássicos Ira Levin Ana Cláudia Brito André Mehmari Éser Menezes Luiz Afonso Montanha Davson de Souza Fábio Cury Marcos Aragoni "O CD de Ira Levin é minha escolha como a melhor gravação de piano solo de 2006. Sua técnica é prodigiosa e suas transcrições estão entre as melhores de todos os tempos. Ele capta sons ao piano nunca ouvidos antes, um arco-íris de cores. É arrebatador. Gregor Benko, fundador do International Piano Archives (IPA) “Bravíssima a pianista Ana Claudia Brito...com técnica brilhante e refinada". Revista Suono, Itália "Duo Brasilis apresenta uma versão excelente e digna de elogio, já que captaram o espírito dos Quadros Tangueros" José Carli, compositor "André Mehmari é um gênio precoce de imaginação vibrante e generosa.” Mauro Dias, Estado de São Paulo Patrocínio: CONCERTO, setembro de 2006, nº 121 ÍNDICE 2 Carta ao Leitor 4 Cartas 6 Contraponto Notícias do mundo musical. 12 Atrás da Pauta Coluna mensal do maestro Júlio Medaglia. 13 Nossos Músicos Homero Velho, barítono. NOSSA CAPA 14 Em Conversa A capa desta edição mostra a fachada do Teatro Entrevista com a compositora Jocy de Oliveira. -

Acclaimed Israeli-American Pianist Daniel Gortler in Recital at the Jewish Museum May 24

Acclaimed Israeli-American Pianist Daniel Gortler in Recital at the Jewish Museum May 24 Theme and Variations Features Works by Corigliano, Mendelssohn, Beethoven, and Schumann New York, NY, April 23, 2018 – The Jewish Museum will present Israeli-American pianist Daniel Gortler performing Theme and Variations, a concert honoring American composer John Corigliano’s 80th birthday, on Thursday, May 24 at 7:30pm. This is Mr. Gortler’s fourth recital at the Jewish Museum. The concert program, which explores the idea of “variations on a theme,” features Corigliano’s Fantasia on an Ostinato together with Mendelssohn’s Variations sérieuses, Op. 54, Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 30 in E major, Op. 109, and Schumann’s epic Symphonic Etudes, Op.13 along with the five posthumous variations. Tickets for the May 24 concert are $24 general; $18 students and seniors; and $14 Jewish Museum members. Further program and ticket information is available online at TheJewishMuseum.org/calendar or by calling 212.423.3337. The Jewish Museum is located at Fifth Avenue and 92nd Street, Manhattan. The recital program will include: Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Variations sérieuses, Op. 54 Published 1841 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Piano Sonata No. 30 in E major, Op. 109 Published 1820 Vivace ma non troppo - Adagio espressivo Prestissimo Gesangvoll, mit innigster Empfindung. Andante molto cantabile ed espressivo John Corigliano (b. 1938) Fantasia on an Ostinato Published 1985 Intermission Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Theme and Variations, Symphonic Etudes Op. 13 (with the 5 Posthumous Variations ) Published 1837/1852 Felix Mendelssohn: Variations sérieuses, Op. 54 This is Mendelssohn's most-often performed substantial piano work. -

B 2019 BAJA-PLIE.Pdf

1 SUMARIO MUNICIPAL DE SANTIAGO DE MUNICIPAL 5 Bienvenidos BALLET PIANISTAS PEQUEÑO MUNICIPAL 6 - 7 Directorio 51 La Cenicienta 90 Filippo Gamba 120 Ballet: La Cenicienta 8 - 9 Auspiciadores Prokofiev / Haydée Schubert / Brahms / Debussy 121 Ballet: Raymonda 52 - 53 Raymonda 90 Bruno Gelber 122 Concierto dramatizado: Cuadros CUERPOS ESTABLES Glazunov / Ortigoza Beethoven / Schumann / Chopin de una exposición 12 Orquesta Filamónica de Santiago 54 - 55 Eugenio Oneguin 91 Danor Quinteros 123 Ópera: El oro del Rin 13 Ballet de Santiago Tchaikovski / Cranko Chopin / Enescu / Ravel 124 Ballet: El pájaro de fuego 14 Coro del Municipal de Santiago 58 - 59 Festival Stravinsky 91 David Fray 125 Ópera: La italiana en Argel 15 Voces Blancas - Coro de niños del 6to Festival de coreógrafos Bach 128 Ballet: La Sylphide Municipal de Santiago 60 - 61 La casa de los espíritus 94 Lilya Zilberstein 129 Concierto dramatizado: Las maderas de 16 Orquesta de Cámara Domínguez / Yedro Scriabin / Rachmaninov / Beethoven Robin Wood del Municipal de Santiago 64 - 65 La Sylphide 94 Olli Mustonen 129 Concierto dramatizado: El rey que quería 17 Escuela de Ballet Løvenskjold / Schaufuss según Bournonville Tchaikovski / Chopin / Mustonen / Prokofiev ser músico del Municipal de Santiago 67 Cascanueces 95 Daniel Gortler 130 - 131 Precios y ubicaciones 19 - 21 Equipo Artístico Tchaikovski / Pinto Beethoven / Corigliano / 68 - 69 Ubicaciones y precios Schumann / Mendelssohn ARTE VIVO ÓPERA 96 - 97 Ubicaciones y precios 134 XVII Festival Fernando Rosas 27 Ópera Mía - Gala de -

Wwciguide June 2020.Pdf

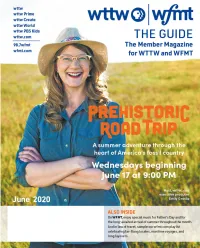

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, we are excited to bring you a new three-part series, Preshistoric Road Renée Crown Public Media Center 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Trip, written and hosted by Emily Graslie (meet Emily on page 4!), who will take you on Chicago, Illinois 60625 an epic adventure through America’s dinosaur country in search of mysterious creatures and bizarre ecosystems Main Switchboard that have shaped Earth as we know it. Explore the (773) 583-5000 Member and Viewer Services companion website, wttw.com/prehistoricroadtrip, for (773) 509-1111 x 6 an interactive road trip map, a behind-the-scenes travel journal, and video extras. Websites wttw.com WTTW brings you more trailblazing women in June, wfmt.com with new American Masters profiles of film icon Mae West and award-winning author Toni Morrison; Holland Publisher Taylor’s portrayal of legendary Texas governor Ann Anne Gleason Art Director Richards; historian Lucy Worsley tracing Royal History’s Tom Peth Myths and Secrets; and a Great Performances portrait of feminist Gloria Steinem, WTTW Contributors Julia Maish among others. On wttw.com, watch an archival interview with Morrison and meet Lisa Tipton some recent Illinois female political figures, from labor activist Agnes Nestor to WFMT Contributors environmental activist Hazel Johnson. Andrea Lamoreaux At WFMT, mindful that Chicago’s summertime classical music festivals and other Advertising and Underwriting live performances are on pause for this season, we hope to fulfill that need with a new WTTW weekly series, Best of the Grant Park Music Festival; our Maestro’s Choice series from Nathan Armstrong the Chicago Symphony Orchestra; and favorite past productions from Lyric Opera of (773) 509-5415 Chicago.