PDF (This Accepted Version May Not Correspond Exactly to the Published

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Somerset's Common Works Programme 2015/16

Somerset's Common Works Programme 2015/16 - Q3 Progress The Common Works Programme shows the flood risk and water management works Somerset's Flood Risk Management Authorities are doing, funded from their own budgets. The last section, labelled joint, is for projects that are joint funded, including those that SRA funds are contributing to Flood Risk For removed For removed Project Management Timescale for schemes - schemes - Ref Project Name District Parish Description Flood Risk Source Progress Comments/Issues Stage Authority Implementation Reason for Further (Funder) removal Action 1. Improvement Schemes - Environment Agency Joint Programme of Work attracting either Government Grant in Aid or Local Levy (WRFCC) funding (see map for EA schemes) www.somersetriversauthority.org.uk/about-us/board-and-partners/board-meetings-and-papers/?entryid108=97703 Carry out repairs to defence wall and reinstate flood bank to Initial site visit has taken place. EA 1 Brue Glastonbury to Cripps Mendip Wedmore Design EA Main River 2015-16 defence level G = on course for delivery in 15/16 Works are ongoing Picked up on IDB Enhanced EA 1 Brue Glastonbury to Cripps Mendip Wedmore Desilt and pull banks on River Brue EA Main River 2015-16 R = no longer proposed for delivery in 15/16 by maintenance EA programme None Lewis Drove Tilting Weir - Gate major mechanical maintenance, This work is being carried out by EA 2 North Drain Mendip Burtle EA Main River 2015-16 repair motor and gearbox G = on course for delivery in 15/16 MEICA Funding for EA 3 Burnham - Highbridge -

Minutes of Parish Council (PC) Meeting Held As a Consultative Virtual Meeting Via Zoom Software on Wednesday 28Th October 2020 at 7.00Pm

North Cadbury & Yarlington Parish Council Clerk: Mrs Rebecca Carter, Portman House, North Barrow, Somerset, BA22 7LZ Tel: 01963 240226 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.northcadbury.org.uk “Draft” Minutes of Parish Council (PC) Meeting held as a consultative virtual meeting via Zoom software on Wednesday 28th October 2020 at 7.00pm Councillors Present (remotely): Malcolm Hunt (Chairman) Alan Bartlett (Vice Chairman) Sue Gilbert Karen Harris Roger House Andy Keys-Toyer Bryan Mead Archie Montgomery Alan Rickers John Rundle Katherine Vaughan In Attendance (remotely): C.Cllr M Lewis, D.Cllr H Hobhouse, D.Cllr Kevin Messenger, the Clerk, Mr A Tregay, Boon Brown and nineteen members of the public. Public Session There were no comments from the public. Clare Field, Ridgeway Lane, North Cadbury – Presentation of Initial Plans for Development Presentation by Mr A Tregay, Boon Brown to PC of initial conceptual plans on scheme at Ridgeway Lane prior to formal consultation with PC, neighbours/residents. The Chairman informed residents that the presentation by Mr Tregay would not constitute a formal consultation. Mr Tregay had given his assurance to the Chairman that the PC and neighbours/residents would have the opportunity to comment and ask questions during the formal consultation process at pre- application and post-application stages, which would be held at a later date, which was also confirmed by Mr Tregay. Mr Tregay stated that this was the start of a constructive dialogue with the PC in order to give an indication of the proposed development during the early stages and to hopefully receive feedback. The aim was to keep the PC and neighbours informed as much as possible. -

North Cadbury Neighbourhood Plan Heritage Assessment on Behalf of North Cadbury and Yarlington Parish Council August 2020

North Cadbury Neighbourhood Plan Heritage Assessment on behalf of North Cadbury and Yarlington Parish Council August 2020 kim sankey │ architect angel architecture │ design │ interiors Angel Architecture Ltd Registered in England at Unit 4, Herringston Barn, Herringston, Dorchester, Dorset DT2 9PU _____________________________________________________________________ North Cadbury Neighbourhood Plan Heritage Assessment August 2020 NORTH CADBURY Key Features The special interest of North Cadbury lies in its origins as a rural estate village (formerly Cadbury Estate) of mixed farmland demarked by ancient enclosed hedgerows with some C17 and C18 modification. On the edges are C19 historic orchards, bounded by mature hedgerows, and several farmsteads. The orchards are a particularly strong landscape feature in terms of social history and culture as they represented an intensively productive use of land, providing cider for the labouring classes while also allowing the grazing of sheep and poultry. There are many listed buildings but most prominent are the Church and Cadbury Court at the historic core around which development is concentrated. The southern edge of the Conservation Area is characterised by the parkland setting of the Court. Under the ownership of Sir Archibald & Lady Langman the estate introduced scientific methods of farming in the 1930’s. The Langman’s prosperity, as a result of this innovation, is evident in the provision of the new village hall opposite Glebe House on Woolston Road. Although most of the other farms have been converted to residential use, Manor Farm remains the manufacturing base for renowned Montgomery Cheddar and Ogleshield cheeses. The River Cam, which rises in Yarlington, runs along the western edge of North Cadbury and through Brookhampton. -

Scoping Report and Project Plan

North Cadbury and Yarlington Neighbourhood Plan Initial Scoping Report and Project Plan SCOPING REPORT – INITIAL FILE NOTE Prepared on behalf of North Cadbury and Yarlington Parish Council SEPTEMBER 2019 1. INTRODUCTION This report has been prepared by Jo Witherden BSc(Hons) DipTP DipUD MRTPI of Dorset Planning Consultant Ltd, for North Cadbury and Yarlington Parish Council. The Parish Council is the qualifying body authorised to act in preparing a neighbourhood development plan in relation to the North Cadbury and Yarlington Neighbourhood Plan area. The purpose of this report is to identify at an early stage what issues that relate to development are likely to be most important to the community, and are something that the Neighbourhood Plan can potentially influence. This will then guide the early stages of evidence gathering and consultation, and initial project plan, to ensure that the time and resources spent on preparing the Neighbourhood Plan are focused on achieving the desired outcomes. NEIGHBOURHOOD PLANS A Neighbourhood Plan, when made, becomes part of the development plan for the area, alongside the Local Plan. Together they set out the policies that are used to decide what types of building work or other development will generally be allowed, and what should be refused. They can also say what buildings or places should be protected, and why. Having a Neighbourhood Plan won’t change the area overnight. Its key influence is on decisions made by on planning applications. Landowners (or developers) will still need to make planning applications to the District Council, who will consult on these before making a decision to permit or refuse the proposed development. -

So O T H Wgrs-T FISHERY SURVEY of the RIVER YEO CATCHMENT

So o TH W G r S - T FISHERY SURVEY OF THE RIVER YEO CATCHMENT 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 This survey of the catchment was undertaken between April 1993 and September 1993. The rivers surveyed were the Yeo, Wriggle, Sutton Bingham Streamsv Cam and Gallica. 1.2 The primary aim was to collect fisheries data on the Yeo catchment as part of a 'rolling1 survey programme for all catchments in the North Wessex Area of the National Rivers Authority. 1.3 It is the first time the catchment has been surveyed in its entirety, the last survey in the catchment being on the upper Yeo betveen Mudford and Sherborne in 1986. 2. TOPOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY 2.1 The River Yeo, a major tributary of the River Parrett, has its source at Seven Sisters Veil, near Charlton Horethome. From here it falls 100m to its confluence vith the Parrett at Langport. Belov Ilchester much of the Yeo is artificially embanked, vith levels rising to 3m above adjacent fields. The catchment totals 398km2. 2.2 The River Cam rises near Jack Whites Gibbet, and has a catchment of 45 sq Km. The ground levels in the area vary betveen 17m and 183m OND at Yeovilton and Bratton Hill respectively. 2.3 The Wriggle rises at Batcombe Hill and flovs approximately north to the confluence vith the River Yeo at Bradford Abbas. It has a catchment of 54.2 km2. 2.4 The Gallica rises near Melbury Sampford and flovs in a northerly direction to its confluence vith the Sutton Bingham Stream approximately 5km away. -

Unexpected Discovery of a Funnel Beaker Culture Feature at the Kraków Spadzista (Kraków-Zwierzyniec 4) Site

FOLIA QUATERNARIA 87, KRAKÓW 2019, 5–26 DOI: 10.4467/21995923FQ.19.001.11494 PL ISSN 0015-573X UNEXPECTED DISCOvery OF A FUNNEL BEAKER culture feature at ThE KRAKÓW Spadzista (KRAKÓW-zWIERzYNIEC 4) SITE Jarosław Wilczyński1, Marek Nowak2, Aldona Mueller-Bieniek3, Magda Kapcia3, Magdalena Moskal-del hoyo3 Authors’ addresses: 1 – Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals, Polish Academy of Sciences, Sławkowska 17, 31-016 Kraków, Poland, e-mail: [email protected], ORCID: 0000-0002-9786- 0693; 2 – Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University, Gołębia 11, 31-007 Kraków, Poland, e-mail (cor- responding author): [email protected], ORCID: 0000-0001-7220-6495; 3 – W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences, Lubicz 46, 31-512 Kraków, Poland; A. Mueller-Bieniek, e-mail: a.mueller@ botany.pl, ORCID: 0000-0002-5330-4580; M. Kapcia, e-mail: [email protected], ORCID: 0000-0001- 7117-6108; M. Moskal-del hoyo, e-mail: [email protected], ORCID: 0000-0003-3632-7227 Abstract. The paper presents a Neolithic feature discovered in trench G of the widely-known Paleolithic Gravettian site at Kraków Spadzista. Pottery and lithic artefacts as well as archaeobotanical data and radiocarbon dates demonstrate the existence of a stable human occupation with an agricultural economy. Due to the small number of distinctive fragments of pottery, both the Wyciąże-złotniki group and the Funnel Beaker culture have to be taken into account in the discussion on the cultural attribution of the feature. The obtained absolute dates make a connection with the latter unit more probable. Keywords: Kraków Spadzista, Neolithic, pottery, lithics, archaeobotany INTRODUCTION Location of the site Kraków Spadzista site is located on the high northern headland of Sikornik, a two- peaked hill in the eastern part of the Sowiniec Range in Kraków measuring over 3 km in length (Fig. -

South Somerset District Council Local Plan Review

South Somerset District Council Local Plan Review The Potential for Rural Settlements to be Designated ‘Villages’ November 2018 Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 2 Context 1 3 Methodology 3 4 Settlement Appraisal 13 5 Conclusions 23 Appendix 1 - Complete list of Rural Settlements in the District subject to this Appraisal 24 Appendix 2 - Settlement Maps; Constraints and Community Service Locations 25 Appendix 3 – Location Map of Settlements 58 1. Introduction 1.1 This paper considers the suitability of the District’s many Rural Settlements for growth. The current Local Plan does not allocate housing and employment to specific villages, seeking to direct most development to Yeovil, the Market Towns and Rural Centres. However, new housing has been delivered in the Rural Settlements far in excess of what the Local Plan anticipated; and similarly, new commercial buildings have, in the main, been provided away from the established employment locations and sites allocated for that purpose. Rather than continue with this somewhat arbitrary situation, the Review of the Local Plan offers the opportunity to look again at the various smaller settlements around the District to ascertain which might offer the best and most sustainable locations for limited growth and possible designation as ‘Villages’. 1.2 The Review of the Local Plan has also resulted in the potential removal of the role of ‘Rural Centre’ from Stoke sub Hamdon. This is because the settlement has many constraints and the number of commercial outlets in the centre is relatively restricted. It could instead be designated a ‘Village’ in recognition of its size and numbers of other facilities relative to the remaining Rural Settlements. -

The Earthworks at Altheim

Sprawozdania Archeologiczne, 2017, 69, s. 71-82 SPRAWOZDANIA ARCHEOLOGICZNE 69, 2017 PL ISSN 0081-3834 DOI: 10.23858/SA69.2017.004 Thomas Saile*, Martin Posselt**, Bernhard Zirngibl*** THE EARTHWORKS AT ALTHEIM ABSTRACT Saile T., Posselt M. and Zirngibl B. 2017. The earthworks at Altheim. Sprawozdania Archeologiczne 68, 71-82. In 2012, fi eldwork recommenced at the Altheim earthwork, discovered more than a century ago. The inves- tigation in its immediate environs revealed a second ditched enclosure from the Altheim period, south-east of the previously known structure. The two enclosures are spatially related to one another. It was found that se- veral decimetres of soil have been eroded during the last hundred years in the area of the north earthwork; the very substance of both monuments is acutely threatened. The fi rst radiocarbon datings, carried out on samples of domestic animal bone, allow both enclosures to be dated to the 37th/36th century BC and suggest a temporal sequence of the ditches. Certain earlier observations, namely the high proportion of arrowheads among the fl aked stone tools and the very low proportion of bones from wild animals, were confi rmed by the new excava- tion. The southwest-northeast orientation of the structures’ long axes permits an archaeoastronomical interpre- tation: knowledge obtained from the observation of natural phenomena was transferred to architecture. The new investigation sheds further doubt on the interpretation of the enclosures as fortifi cations. Keywords: Later Neolithic, Altheim culture, -

Foreword to the Draft Queen Camel Neighbourhood Plan 2019-2030

Foreword to the Draft Queen Camel Neighbourhood Plan 2019-2030 I have pleasure in commending this Neighbourhood Plan covering the development of the village in the period to 2030. The Plan, when adopted, will form part of a hierarchy of plans at local levels within the National Planning Policy Framework. The NPPF provides a strict framework for developing plans, particularly on housing, which we have carefully observed. Taking this Plan through its remaining stages so that it can be a final approved Neighbourhood Plan to support all that we want is a very significant step for the village. The remaining steps are as follows; • Submission of the plan to South Somerset District Council (SSDC) for examination • Final revision of the plan before submission to the parish for approval by referendum • When approved by referendum, the Neighbourhood Plan is formally adopted. The background to the process to develop the plan is set out in the detailed sections which follow. I would emphasise that a very detailed analysis of the wishes of the village, covering in particular the housing needs and the availability of land for development, has been made by the Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group of the Parish Council (NPSG) along with the Parish Council itself and its advisor from Dorset Planning Consultant Limited and South Somerset District Council. Therefore do read the policies and the background to them thoroughly as a lot of careful analysis of what could be appropriate for the village is described in this document. The Parish Council have carefully considered the range of comments that were made on the draft plan and made some changes as a result. -

1267-08 Louwe Kooijmans 22.Indd 261 03-06-2008 15:06:29 262 PIERRE PÉTREQUIN ET AL

ANALECTA PRAEHISTORICA LEIDENSIA This article appeared in: PUBLICATION OF THE FACULTY OF ARCHAEOLOGY LEIDEN UNIVERSITY BETWEEN FORAGING AND FARMING AN EXTENDED BROAD SPECTRUM OF PAPERS PRESENTED TO LEENDERT LOUWE KOOIJMANS EDITED BY HARRY FOKKENS, BRYONY J. COLES, ANNELOU L. VAN GIJN, JOS P. KLEIJNE, HEDWIG H. PONJEE AND CORIJANNE G. SLAppENDEL LEIDEN UNIVERSITY 2008 1267-08_Louwe Kooijmans_Overdruk1 1 16-06-2008 13:39:01 Series editors: Corrie Bakels / Hans Kamermans Copy editors of this volume: H arry Fokkkens, Bryony Coles, Annelou van Gijn, Jos Kleijne, Hedwig Ponjee and Corijanne Slappendel Editors of illustrations: Harry Fokkkens, Medy Oberendorff and Karsten Wentink Copyright 2008 by the Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden ISSN 0169-7447 ISBN 978-90-73368-23-1 Subscriptions to the series Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia and single volumes can be ordered exclusively at: Faculty of Archaeology P.O. Box 9515 NL-2300 RA Leiden The Netherlands 1267-08_Louwe Kooijmans_Overdruk2 2 16-06-2008 13:39:02 22 Neolithic Alpine axeheads, from the Continent to Great Britain, the Isle of Man and Ireland Pierre Pétrequin Alison Sheridan Serge Cassen Michel Errera Estelle Gauthier Lutz Klassen Nicolas Le Maux Yvan Pailler 22.1 INTRODUCTION view as 21st century ‘technicians’, once the axeheads had Within the source area from which Alpine axeheads passed beyond the geographical zone of their fi rst users, circulated around western Europe, two groups of quarries located to the northwest and west of the Alps, they took on and of secondary exploitation sites close to the outcrops have a socially-determined role over and above their primary func- recently been identifi ed in Italy. -

Mobilities, Entanglements and Transformations in Neolithic Societies of the Swiss Plateau (3900 – 3500 BC)

Bern Working Papers on Prehistoric Archaeolog y No. 1 Institute of Archaeological Sciences Prehistory Albert Hafner Caroline Heitz Regine Stapfer March 2016 Mobilities, Entanglements, Transformations. Outline of a Research Project on Pottery Pratices in Neolithic Wetland Sites of the Swiss Plateau Project’s Title: Mobilities, Entanglements and Transformations in Neolithic Societies of the Swiss Plateau (3900 – 3500 BC) Funding: Swiss National Science Foundation Project No 100011_156205 Project management: Prof. Dr. Albert Hafner Institute of Archaeological Sciences Prehistory University of Bern Switzerland Project management: Prof. Dr. Vincent Serneels Department of Geosciences Section of Earth Sciences, Archaeometry University of Fribourg Switzerland Impressum Series ISSN: 2297- 8607 e-ISBN: 978-3-906813-12-7 (e-print) DOI: 10.7892/boris.77649 Editors: Albert Hafner and Caroline Heitz Institute of Archaeological Sciences, Prehistory University of Bern Muesmattstrasse 27 CH-3012 Bern This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Inter- national License English language editing: Andrew Lawrence, Sharon Shellock, Ariane Ballmer Layout: Designer FH in Visual Communication Susanna Kaufmann Photographs (front page): Today’s shore of Lake Neuchâtel, Pfyn and Michelsberg pottery from the Neolithic bog settlement of 2 Thayngen-Weier, Northern Switzerland (Caroline Heitz). Table of Contents 1. Aims and research questions 4 2. State of research 5 3. Case studies 10 4. Mixed methods research-design 13 5. Some words on applied methods -

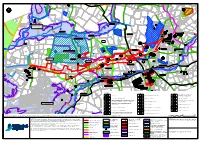

A303 SPARKFORD to ILCHESTER This Material May Not Be Copied, Distributed, Sold Or Published Without the Formal Permission of Land Registry

14 Ferndale Hill 49.8m MP 133.5 Pond Farm Tar-Wen 21.4m CG Saumerez Wolverlands 29.6m 23.5m CG Broadway 10 STEART LANE 1.83m RH 1.83m RH Ward Bdy 4 46.8m Pond 24.0m Ty-Llawen Pond Tennis Court Bower's Farm Def New (Track) 1.83m RH 26.7m Close Wrong-thorn 1.83m RH BILL'S LANE Steart 21.5m 26.4m 1 Playing Field 44.6m 5 28.8m 27.9m 26.9m Track Woodlands Farm 25.7m 1 Pond NIGHTINGALE LANE 4 Pond Ward Bdy Track 28.9m CS 24.7m ED and Ward Bdy 41.0m Issues Track Pond GP 27.4m 1.83m RH Camel Leas 26.1m 26.6m Pond 1.83m RH Def Nightingale Cottage Ward Bdy Pond Def 20 Manor Drain Woodside Villa Farm Lay-by Drain Cottage Ward Bdy Woodlands 49.8m Fortyacres Farm 29.9m GP Sparkford Wood Def 32.0m FB Def 33.8m Ponds 50.6m FB Woodgate Cottage Ponds Ward Bdy 1.83m RH SPARKFORD ROAD Pond Pond River Cary Track ED & Ward Bdy Track MP 133.75 Newhaven Pond 21.0m 1.83m RH 54.3m Track 37.2m 49.1m Lay-by Drain STEART LANE Def Pond Sluice 19.5m Pond Pond 53.4m Pond Pumping Station Issues Pond Tank 1.83m RH Pond Pond Forty Acre Copse Pond River Cary 1.83m RH Upper Wood RAG LANE (Track) Dairy House Issues 1.83m RH Pond Trackside Farm 1.83m RH Woodside Court 45.3m Def Weir 23.3m Westacre FB Ward Bdy Ppg Sta Def Issues Pond 50.8m Drain Pond Issues Pump 17.3m Cary Fitzpaine House 45.8m 1.83m RH Cistern Drain The Chestnuts 1.83m RH Pond Pond MS Ward Bdy 1.83m RH Drain Pond 1.83m RH Cary The Old Cottage Stables ESS Middle Barn Pond FB Issues 47.0m West Side Barn Pond Woodside Farm Silos WB Garden Cottage MP 134 Haynes Motor Pond The Rookery Bampfylde Museum A 37 5 Two