Speaker & Gavel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Idtxution Worldwatch Inst., Washington, P.C

SE-022 608 AOTROR' Hates, Denis 'rtmiAt Energy: The Solar P'rosnect.Worldwatch Paper 11,,,, IdTxuTION Worldwatch Inst., Washington, P.C. Mar .71 VA".4.CDAtE iegible due to small 1141$ 83p.; Parts may be mar inally type ;AVAILABLE FROM Worldwaich Institute, 776 Massachusetts Avenue, ; W.W., Washington, D,C.20038 ($2.:00 BIM PRICE MP-$0.83 P/us Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS DESCRIPTORS Depleied Resources; *Energy; Environment; *Environmental Influences; Fuels; *Futures (of .Society); Natural Resources; *Solar Radiation; *Technology; *World Problems TDENTIFIERS *Solar Energy ABSTRACT 0 T Tliis paper, one of 'a series published by the Worldwatch Institlite to identify i.snd focus atteption onglobal . problemsi is adapted fro..the .author's book, "Rays of Hope: rhe Transition to a Post-etr.eum World.v The author examines the qurtent energy problems of the world, and determines thatthe 'energy patterns of the past dare not the prologue to the future. The inadequacies associated with energy alternatives-to petrole9m,sxch as coal and nuclear fusion, areidentified and discusSed. Thus, soctety- is left with only the, solar oPtions: wind,falling water, biomass, and dtrect sunlight. The ;historical dévelopmept,rtechnol'ogy, 'and current status of each' of the sdlar options' isdetailed. The social and politiCal ramifications. of theconversion to a society based On solar energy are hypotheized.The.author° concludes tthat 'the conversion to °solar energy is tec'hnically feasible,ecoltiomically sound, and environmentally' attractive. (BT) / _> 4********4F******************************(****4i*********1*******,********** * * Documents, acquired by ERIC inClide maiy,informal uni*nblished * materials not,available from other source4 .ERIC makes every ef fort * * ;to obtain the best copy available..Neve14heless, items of marginal , * * reproducibility are oftenencOuntered a'#this affects the quality * * o'c the microfiChe and hardcopyreproluet ons BRIC makes available -* * via the ERIC Document ReproduotionServi e(EDRS). -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi'om the original or copy submitted- Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from aity type of conçuter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to r i^ t in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9427761 Lest the rebels come to power: The life of W illiam Dennison, 1815—1882, early Ohio Republican Mulligan, Thomas Cecil, Ph.D. -

Attractions by Stop – Northbound

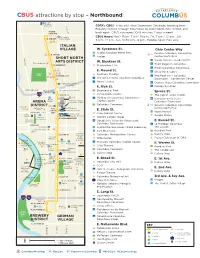

® attractions by stop – Northbound Kroger .5 miles from stop N. 4TH ST. COTA's CBUS® is the city's free Downtown Circulator, traveling from Brewery District, through Downtown to Short North Arts District, and 3RD AVE. & SAY AVE. back again. CBUS runs every 10-15 minutes, 7 days a week! The Market CBUS Hours: Mon.- Thurs. 7 a.m- 10 p.m., Fri. 7 a.m. - 12 a.m., Sat. E. 2ND AVE. Italian Village 9 a.m.- 12 a.m., Sun. 10:30 a.m.- 6 p.m., Holiday hours may vary. ITALIAN VILLAGE W. Sycamore St. Ohio Center Way Scioto Audubon Metro Park Greater Columbus Convention E. 1ST AVE. Kroger Center South End NEIL AVE. SHORT NORTH ARTS DISTRICT W. Blenkner St. Visitor Center – inside GCCC The Candle Lab Hyatt Regency Columbus E. WARREN ST. Shadowbox Live Hilton Columbus Downtown E. Mound St. Drury Inn & Suites Goodale Southern Theatre Park E. RUSSELL ST. Red Roof Inn + Columbus The Westin Great Southern Columbus Downtown – Convention Center Home2 Suites Le Méridien Columbus, Crowne Plaza Columbus Downtown The Joseph E. Rich St. Canopy by Hilton GOODALE BLVD. Hampton Inn The Cap at Union Station Bicentennial Park & Suites Spruce St. SPRUCE ST. Cultural Arts Center The Cap at Union Station Holiday Inn Columbus Downtown – North Hampton Inn & Suites Market Greater Columbus Capitol Square ARENA Arnold Convention Center Columbus Downtown Statue Columbus Commons Hilton Greater Columbus Convention Huntington DISTRICT Nationwide Hyatt Regency Center North End Park Arena OHIO E. State St. CENTER Drury Inn & Suites North Market NATIONWIDE BLVD. WAY Ohio Judicial Center Visitor Red Roof Plus+ Center Crowne Plaza Canopy by Hilton Arnold Statue Nelson’s World’s Largest Gavel Convenience E. -

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

Invisible Man By Ralph Ellison Back Cover: Winner of the National Book Award for fiction. Acclaimed by a 1965 Book Week poll of 200 prominent authors, critics, and editors as "the most distinguished single work published in the last twenty years." Unlike any novel you've ever read, this is a richly comic, deeply tragic, and profoundly soul-searching story of one young Negro's baffling experiences on the road to self-discovery. From the bizarre encounter with the white trustee that results in his expulsion from a Southern college to its powerful culmination in New York's Harlem, his story moves with a relentless drive: -- the nightmarish job in a paint factory -- the bitter disillusionment with the "Brotherhood" and its policy of betrayal -- the violent climax when screaming tensions are released in a terrifying race riot. This brilliant, monumental novel is a triumph of storytelling. It reveals profound insight into every man's struggle to find his true self. "Tough, brutal, sensational. it blazes with authentic talent." -- New York Times "A work of extraordinary intensity -- powerfully imagined and written with a savage, wryly humorous gusto." -- The Atlantic Monthly "A stunning blockbuster of a book that will floor and flabbergast some people, bedevil and intrigue others, and keep everybody reading right through to its explosive end." -- Langston Hughes "Ellison writes at a white heat, but a heat which he manipulates like a veteran." -- Chicago Sun-Times TO IDA COPYRIGHT, 1947, 1948, 1952, BY RALPH ELLISON All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. For information address Random House, Inc., 457 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10022. -

Dean's Message

Dean’s Message Dear Friends, This is an exciting time to be dean of Capital University Law School. When I joined the Law School community in July 2004, I set out a number of challenges and opportunities for us to work toward together. I am pleased to report that the past year has been an exciting and energizing one at the Law School and that great progress has been made, but it is just the beginning of many more Dean Jack A. Guttenberg great things to come for Capital University Law School. Ohio State Bar Association Annual Convention in The full, reconstituted Alumni Association Board May, the Alumni Association recognized outgoing has met twice, after a steering group spent many OSBA President Heather Sowald, L’79, as Alumnus months working on a draft strategic plan for the of the Year, for her commitment to giving back to the Board. My charge to the steering group was to profession, her community and to the Law School. create a plan to re-engage and reconnect our We have also implemented a new series highlighting alumni with each other and with the Law School. the great achievements of our faculty, alumni and The Board has taken my charge to heart. While students called Profiles in Success. there is still work do be done, the plan identifies a number of exciting events and projects for the Programs to improve the performance of Law School coming year and beyond. Plan to join us for our first graduates on the Ohio Bar Exam are moving forward annual Alumni Weekend, April 28-29, 2006. -

The National Capitol

196 The National Capitol foot is a bronze bust by Vincenti of the Chippewa Chief, Beeshekee, the Buffalo.On the walls above the landing is the popular picture known as "Westward the Course of Empire takes its Way." It is the work of the genial German-born artists Emanuel Leutze, an historical painter of some distinc- tion, and its title is a quotation from Bishop Berkeley.The scene is a pano- rama, impossible in extent, of western country.In the foreground are depicted the struggles and privations of an early wagon-train crossing a pass in the Rocky Mountains.Beyond are spouting geysers, grand cafions and the El Dorado, stretching like a mirage of hope before the eyes of the weary travelers.The view is truly an inspiring one. In the fanciful border to the right, the artist has placed a portrait of Daniel Boone and, beneath it, the appropriate quotation from Jonathan M. Sewall's Ej5ilogue /0 Cab: "The spirit moves with its allotted spaces, The mind is narrowed in a narrow sphere." The corresponding portrait, worked into the border upon the left, is that of Captain William Clarke,whose pioneer story is so fascinatingly told by Wash- ington Irving.Its quotation also is from Sewall: No pent-up Utica contracts our powers, But the whole boundless continent is ours." In the long narrow border beneath is seen the Golden Gate, the entrance to the harbor of San Francisco. We owe the picture in great part to General Meigs, who took the respon- sibility of contracting for it with the artist and who, for his pains, received at the time much criticism on the score of extravagance. -

Complete Issue 10(4)

Speaker & Gavel Volume 10 Article 1 Issue 4 May 1973 Complete Issue 10(4) Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/speaker-gavel Part of the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation (1973). Complete Issue 10(4). Speaker & Gavel, 10(4), 86-120. This Complete Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Speaker & Gavel by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. PWMoTl. s(p et al.: Complete Issue 10(4) speakep An6 qavel P-..::-'.Ls SECT.c. j .s ■ 1973 ^ STATL Cv^LLSG- LIBP,.-*.;,'/ ik. volume to, numBeR 4 may, 1973 Published by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato,1 Speaker & Gavel, Vol. 10, Iss. 4 [], Art. 1 SPEAKER and GAVEL Official publication of Delto Sigma Rho—Tau Kappo Alpha National Honorory Forensic Society PUBLISHED AT LAWRENCE, KANSAS By ALLEN PRESS, INC. Second-class postage paid at Lawrence, Konsas, U.S.A. 66044 Issued in November, Jonuary, Morch ond May. The Journal carries no paid odvertising. NATIONAL OFFICERS (OF DSR-TKA) President: NICHOLAS M. CRIPE, Butler University Vice President: GEORGE 2IEGELMUELLER, Wayne State University Secretory: THEODORE J. WALWIK, Slippery Rock Stote College Treasurer: ROBERT HUBER, University of Vermont Trustee: WAYNE C. EUBANK, University of New Mexico Historian: HEROLD T. ROSS, DePouw University REGIONAL GOVERNORS, MEMBERS AT LARGE, AND REPRESENTATIVES Regional Governors: JOHN A. -

TRACT- Prepared in Recognition of the Bicentennial, This Historic Guide of Iowa Is Intended to Supplement Materialsprepared by the Iowa Curriculum Division

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 111 754 SO 008 616 AUTHOR Pratt, LeRoy G. TITLE Discovering Historic Iowa. American Revolution Bicentennial Edition. INSTITUTION IoWi State-Dept. of Puillic Instrution,Des Moines., PUB DATE 75 NOTE 323p, AVAILABLE FROM Information Services, Department of Public Instruction, Grimes State Office Building, Des Moines, Iowa 50319 ($2.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$15.86 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Colonial History,(United States); Community Cooperation; *Community Education; Educational Resources; Elementary Secondary Education;. Instructional Materials; Reference Materials; *Resource Guides; *Social Studies; Supplementary Reading Materials; *United States4iistory IDENTIFIERS *BicentennialIowa- TRACT- Prepared in recognition of the Bicentennial, this historic guide of Iowa is _intended to supplement materialsprepared by the Iowa Curriculum Division. It provides, inone convenient reference, information for use by teachers, students,. tourists,and others interested in Iowa1s history. Up-tor-date information isgiven on historicalsocieties, museums, archaeological sites, geological areas, botanical preserves, wildlife exhibits, outdoor classrooms, zoos, art centers;., scientific facilities, and places of historicalor cultural interest. The resource unit is arranged in alphabeticaland numerical order. by name and number ofcounty. Names of all known societies, museums, landmarks, sites, natural 'areas, and facilities used for educational purposes are listed alphabeticallyunder each count-y-iAlso-inelndsd-are---a-Ioeation map; an. index; 'a calendar of celebrations, festivals, and historical events;an Iowa map; and an alphabetical index. This resource may be of interestas a model to other states that wish to develop a guide for the Bicentennial. (AuthorpR) *********************************4:************************************ Documents acquired by ERAC-include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other s urces. ERIC makesevery effort 45 * to obtain the best copy available. -

Chapter Sketches, Connecticut Daughters of the American Revolution

ChapterSketches,ConnecticutDaughtersoftheAmericanRevolution ConnecticutDaughtersoftheAmericanRevolution,MaryPhilothetaRoot,CharlesFrederickJohnson MRS. S ARA T. KINNEY STATE REGENT CONNECTICUT DAUGHTERS OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION CHAPTER S KETCHES Connecticut DAUGHTERS O F THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION Ipatron S aints EDITEDY B MARY F HILOTHETA ROOT, A. B. Katherine Gaylord Chapter, Bristol Withn a Introduction by CHARLES FREDERICK JOHNSON, A. A. « « « « i -i PUBLISHED B Y CONNECTICUT C HAPTERS, DAUGHTERS OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION SOLDY B THE E DWARD P. JUDD CO NEW HAVEN . j 2 34021 \9i ' The d atiingist thing in history — simple truth.— Donald G. MITCHELL. IV c o we it to the generations that go before us, and to those which come after us, to perpetuate the memorv and example oj those who in a signal maimer made themselves serviceable to humanitv.— FREDERICK DOUGLASS. Entered a ccording to Act of Congress in the year 1901 by Marv PhilothEta Root. THE T uTTLE, MOREHOUSE A TAYLOR CO., NEW HAVEN, CONN. 1 I by a u nanimous vote of The Regents and Delegates of The Connecticut Chapters to MRS. S ARA T. KINNEY State Regent whose l ong and harmonious regencv has been conspicuous for its manv achievements, and whose wise leadership has won distinction and honor for connecticut daughters of the american revolution BADGEF O OFFICE FOR THE REGENT OF CONNECTICUT. (Votedy b the Chapter Regents and Delegates February, 1903. Designed and made by Tiffany & Co, of New York.) INTRODUCTION N a l etter from America M. Gaston Deschamps says in Lc Temps of the 31st of March, 19o1 : "On trouve encore dans la capitale du Connecticut ces 1 vestiges du passe auxquels les Americains ne sauraient renoncer sans detruire leurs titres de noblesse. -

Complete Issue 7(3)

Speaker & Gavel Volume 7 Article 1 Issue 3 March 1970 Complete Issue 7(3) Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/speaker-gavel Part of the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation (1970). Complete Issue 7(3). Speaker & Gavel, 7(3), 70-104. This Complete Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Speaker & Gavel by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. et al.: Complete Issue 7(3) DONALD 0. OLSON speAkep An6 qavel ☆; volume 7, numise.R 3 mARCh, 1970 Published by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato,1 Speaker & Gavel, Vol. 7, Iss. 3 [], Art. 1 SPEAKER and GAVEL Official publication of Delto Sigma Rho-Tou Kappo Alpha National Honorary Forensic Society PUBLISHED AT LAWRENCE, KANSAS By ALLEN PRESS. INC. Second-closs postage paid at Lowrence, Konsos, U.S.A. 66044 Issued in November, Jonuory, March and Moy. The Journal carries no paid advertising. TO SPONSORS AND MEMBERS Please send oil communications relating Federal Tox. Individuol key orders add 50c. to initiation, certificotes of membership, key The nomes of new members, those elected orders, ond nomes of members to the between September of one year and Notionol Secretory. All requests for September of the following year, authority to initiate and for emblems 'imi' oppeor in the November issue of should be sent to the Notionol Secre- IT SPEAKER ond GAVEL. -

Memorial Record of the Nation's Tribute to Abraham Lincoln

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS DD0E7^1S3bA # A •» O J '> • /% - # *^ * P « o 'bV" VV * 'o v'^ <- *^s* G^ 0' e' . -jrrr <0' V* * *. M'* c^^ '^.- V ..!."% cv * > s • • ^^ /^ ^-^^ o. \> .^LV: f-' 0^ e' ->t' •v^* V W' "^^ ^ x"^" ^0' • ^V > 1 • • . *>->. /^V . » • ** Z,^^'-. *^-.,/ •'"'?^". u^.i^ : '5?^^\\n^.'. 'bV^ ^^j^-^'/ ^^ .0^ "S. «.^^ cy/^-^^yyC^^Lyyz' — : MEMORIAL RECORD NATION'S TRIBUTE TO ABRAHAM LINCOLN. " THE ECHOES OF HIS FUNERAL KNELL VIBRATE THROUGH THE WORLD, AND THE FRIENDS OF FREEDOM OF EVERY TONGUE AND IN EVERY CLIME ARE HIS MOURNERS." Bancroft on Pre&t. Lincoln. -fy „__ C ]M^ I L E D BY B :'^'^^^U ORRIS. VJ l' TV ^, WASHINGTON, D. C. <i W. H. & 0. H. MORRISON. 1865. o ^41:^1 a: U4 \ao^5l* ^ O Q < UJ Bntered according to Act of Congress, by W. H. & 0. H. Moerissn, in the Clerk's OfiBce of the District Court of the U. S. for the District of Columbia. STEREOTVPED Br M'SILL i WITHEROW, WASHINQTON, t. 0. THIS MEMORIAL TRIBUTE TO ABRAHAM LINCOLN, IS DEDICATED TO THE AMERICAN PEOPLE, AND TO THE i'KlENDS OF OUR COUNTRY, AND OF FREEDOM IN EVEEY CLIME. INTRODUCTION. The scenes recorded in this memorial volume form the most wonderful and instructive chapter in hiiman history. They vibrated mournfully through the sensibilities of every American heart, and through all the civilized and Christian nations of the world. It is, therefore, of the highest importance that their permanent record should possess the dignity and value of historic truth and accuracy. Such is this volume. In its preparation the design was to reproduce, in a condensed and connected form, from the public journals of Washington and of the cities through which the illustrious dead was conveyed to his burial place, the graphic pen-pictures painted by the accomplished reporters of the public press. -

117Th Annual Convention and Conference

Maryland State Firemen’s Association Proceedings Of 117th Annual Convention and Conference Held In Ocean City, Maryland June 13 - 19, 2009 Next Meeting To Be Held At Ocean City, Maryland June 12 - 18, 2010 Maryland State Firemen’s Association 117th Annual Convention and Conference Maryland State Firemen’s Association Proceedings Of 117th Annual Convention and Conference Held In Ocean City, Maryland June 13 - 19, 2009 Next Meeting To Be Held At Ocean City, Maryland June 12 - 18, 2010 1 Maryland State Firemen’s Association 117th Annual Convention and Conference TABLE OF CONTENTS Seal and Logo . 3 MSFA Presidents 2008 – 2009 and 2009 – 2010 . 5 MSFA Offifcers (Elected and Appointed) . 7 Committees . 13 Officers & Committee Chairmen Pictures . 36 Past Presidents . 41 Convention Locations . 51 117th Annual MSFA Convention and Conference Program . 52 Report of MSFA Officers and Committees . 189 Ladies Auxiliary Presidents 2008-2009 and 2009-2010 . 249 Ladies Auxiliary Officers . 251 Ladies Auxiliary Convention and Conference Program . 254 Report of Ladies Auxiliary Officers . 258 Credentials Listing Roll Call of Member Departments . 273 Charter, Constitution and By-Laws . 350 MSFA Awards, Rules/Regulations, and Contest/Winners . 354 Parade Award Winners . 471 2 Maryland State Firemen’s Association 117th Annual Convention and Conference Seal of the Maryland State Firemen’s Association The Great Seal of Maryland was used by the Maryland State Firemen’s Association during its first two years (1893-1894.) The second logo of the M.S.F.A. was first used in 1895, and appeared on the Proceedings Book of the Association until 1904, (shown lower left.) In 1905, the logo was changed (shown lower center).