Equal Treatment Bench Book 2013 Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divulgação Bibliográfica

Divulgação bibliográfica Julho/Agosto 2019 Biblioteca da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Coimbra Sumário BASES DE DADOS NA FDUC ........................................................................................ 4 E-BOOKS .................................................................................................................. 6 MONOGRAFIAS ........................................................................................................ 52 Ciências Jurídico-Empresariais................................................................................................................. 53 Ciências Jurídico-Civilísticas ..................................................................................................................... 70 Ciências Jurídico-Criminais ...................................................................................................................... 79 Ciências Jurídico-Económicas .................................................................................................................. 82 Ciências Jurídico-Filosóficas ..................................................................................................................... 83 Ciências Jurídico-Históricas ..................................................................................................................... 88 Ciências Jurídico-Políticas ........................................................................................................................ 94 Vária ...................................................................................................................................................... -

CCBE Charter of Core Principles of the European Legal Profession

Council of Bars & Law Societies of Europe The voice of the European legal profession Rue Joseph II, 40/8 - 1000 Brussels T +32 (0)2 234 65 10 - [email protected] - www.ccbe.eu Charter of core principles of the European legal profession & Code of conduct for European lawyers Edition 2019 The 2019 edition includes the amendments to the commentary on Principle (g) of the Charter approved by the Plenary Session on 17 May 2019. Responsible editor: Philip Buisseret Cover illustration: ©gunnar3000 - Fotolia.com The Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe (CCBE) has as its principal object to represent its member Bars and Law Societies, whether they are full members (i.e. those of the European Union, the European Economic Area and the Swiss Confederation), or associated or observer members, on all matters of mutual interest relating to the exercise of the profession of lawyer, the development of the law and practice pertaining to the rule of law and the administration of justice and substantive developments in the law itself, both at a European and international level (Article III 1.a. of the CCBE Statutes). In this respect, it is the official representative of Bars and Law Societies which between them comprise more than 1 million European lawyers. The CCBE has adopted two foundation texts, which are included in this brochure, that are both complementary and very different in nature. The more recent one is the Charter of Core Principles of the European Legal Profession which was adopted at the plenary session in Brussels on 24 November 2006. -

Vesak Eng.Pdf

Vasak Day and Global Civilization Author : Phra Brahmagunabhorn (P.A.Payutto) Translator : Ven.Asst.Prof. Dr. Phramaha Hansa Dhammahaso Edited : Mr. Robin Philip Moor Graphic Design : Sarun Upansak, Usa Bunjonjad First Printing : 3000 Copies, May 2011 Published by : Mahachulalongkorn rajavidyalaya University 79 M.1, Lam Sai, Wang Noi, Ayutthaya, 13170, Thailand. Tel. +66 (035)24-8000 www.mcu.ac.th Printed by : Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya Press Wat Mahathatu. Tha Prachan, Phra Nakhon, Bangkok 10200 Tel 0-2221-8892 Fax 0-2923-5623 www.mcu.ac.th Preface Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University (MCU) has been privileged to witness and play a crucial role in developing and hosting successful UNDV celebrations from the beginning in 2004/ 2547 to 2011/2554 (except in 2008/2551 – the celebrations were held in Hanoi, Vietnam). As always, we are all very grateful to the Royal Thai Government for its constant support, and thank the Thai Supreme Sangha Council for its blessings, guidance and support. We are indebted, also, to the United Nations for recognizing the thrice-sacred Buddhist holy day. It has been 2554 years since the death of our Great Teacher, and we have gathered here from across the globe, from many nations, to again pay tribute to his birth, enlightenment, and death – occurring on the same day in different years. For the celebrations this year, the Inter- national Association of Buddhist Universities (IABU), created during the UNDV in 2007/2550 by the participating Buddhist higher institutions, plays an important role. The IABU Secretariat now plays a major role in our celebrations, particularly in the academic program of the conference. -

Interfaith Calendar

2018 - 2019 18-month interfaith calendar 18-Month Interfaith Calendar To foster and support inclusive communities, Diversity Awareness Partnership is pleased to present the 2018-2019 18-Month Interfaith Calendar. This publication is a handy guide to observances celebrated across 25 religious traditions in the St. Louis region. When planning your organization’s schedule, refer to our Interfaith Calendar to honor the holidays your friends, neighbors, and colleagues celebrate. Considerations In order to be more accommodating for people who practice different religions, consider the following: FOOD Food and drink are central to many traditions’ rituals and practices. Consider vegetarian, vegan, non-alcoholic, and decaf options, which can accommodate a wide variety of religious and ethical choices. HOURS Some holidays may require individuals to worship or pray during different hours than they may the rest of the year. Consider flexibility that takes into account the work and objectives of your student or employee, rather than the typical time frame when this is normally accomplished. TIME OFF Many organizations have standard holidays for all employees or students that are built around the worldview of a particular religion - Christianity, for example. Consider allowing practitioners of other religions to float these holidays or make shifts in their schedules. Again, the priority should be the quality of the work, not where or when it takes place. DEADLINES/WORK FLOW During holidays that require prayer at late/early hours or that require fasting, some individuals may experience decreased stamina. Examine project schedules or work deadlines to see if they can be adjusted, if need be. PRAYER Some religions require daily or periodic prayer that requires solitude and quiet. -

Legal Ethics

THE GEORGETOWN JOURNAL OF LEGAL ETHICS VOL. VII, NO. 1 SUMMER 1993 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY'S LEGAL ETHICS CODE PART I: AN ANALYSIS OF THE CCBE CODE OF CONDUCT Laurel S. Terry ARTICLES An Introduction to the European Community's Legal Ethics Code Part I: An Analysis of the CCBE Code of Conduct LAUREL S. TERRY* I. WHO PROMULGATED THE CCBE CODE OF CONDUCT AND WHY?........................................... 5 II. To WHOM DOES THE CCBE CODE OF CONDUCT APPLY? . 10 III. WHAT Is THE BINDING FORCE OF THE CCBE CODE OF CONDUCT........................................ 11 IV. WHAT TYPE OF CODE Is THE CCBE CODE OF CONDUCT? . 15 V. AN ANALYSIS OF THE SUBSTANTIVE PROVISIONS OF THE CCBE CODE OF CONDUCT. 17 A. A Description of the Contents of the CCBE Code of Conduct...................................... 18 B. A Discussion of the Substance of the CCBE Code. 18 1. The "Preamble" of the CCBE Code . 19 2. The "General Principles" in the CCBE Code . 23 * Professor of Law, The Dickinson School of Law. B.A. 1973, University of California, San Diego; J.D. 1980, University of California, Los Angeles. I would like to thank the Fulbright Commission for a research grant to work on this article and the innumerable individuals who provided assistance or information, including Dorothy Margaret Donald-Little, Drs. Nicholas and Julie Simon, Dr. Peter Fischer, and the officials of the CCBE, especially including John Toulmin, Q.C., Msr. Denis de Ricci, Dr. Karl Hempel, Dr. Georg Frieders, and Mmse. Janice Webster. In addition, I would like to thank Professor Roger Goebel, Dr. -

Handbook of Religious Beliefs and Practices

STATE OF WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES 1987 FIRST REVISION 1995 SECOND REVISION 2004 THIRD REVISION 2011 FOURTH REVISION 2012 FIFTH REVISION 2013 HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES INTRODUCTION The Department of Corrections acknowledges the inherent and constitutionally protected rights of incarcerated offenders to believe, express and exercise the religion of their choice. It is our intention that religious programs will promote positive values and moral practices to foster healthy relationships, especially within the families of those under our jurisdiction and within the communities to which they are returning. As a Department, we commit to providing religious as well as cultural opportunities for offenders within available resources, while maintaining facility security, safety, health and orderly operations. The Department will not endorse any religious faith or cultural group, but we will ensure that religious programming is consistent with the provisions of federal and state statutes, and will work hard with the Religious, Cultural and Faith Communities to ensure that the needs of the incarcerated community are fairly met. This desk manual has been prepared for use by chaplains, administrators and other staff of the Washington State Department of Corrections. It is not meant to be an exhaustive study of all religions. It does provide a brief background of most religions having participants housed in Washington prisons. This manual is intended to provide general guidelines, and define practice and procedure for Washington State Department of Corrections institutions. It is intended to be used in conjunction with Department policy. While it does not confer theological expertise, it will, provide correctional workers with the information necessary to respond too many of the religious concerns commonly encountered. -

The European Court of Justice at Work: Comparative Law on Stage and Behind the Scenes

Journal of Civil Law Studies Volume 13 Number 1 2020 Article 2 9-28-2020 The European Court of Justice at Work: Comparative Law on Stage and Behind the Scenes Michele Graziadei Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/jcls Part of the Civil Law Commons Repository Citation Michele Graziadei, The European Court of Justice at Work: Comparative Law on Stage and Behind the Scenes, 13 J. Civ. L. Stud. (2020) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/jcls/vol13/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Law Studies by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EUROPEAN COURT OF JUSTICE AT WORK: COMPARATIVE LAW ON STAGE AND BEHIND THE SCENES Michele Graziadei∗ I. Introduction ................................................................................. 2 II. Multilingualism, Translation, and Interpretation at the ECJ ...... 6 III. Comparative Law and the Search for Shared Meaning in European Law ............................................................................ 8 IV. The Keywords, the Concepts, the General Principles ............ 11 V. The Extraterritorial Reach of EU Law and the Comparison of Different Laws ......................................................................... 16 VI. The Transatlantic Dimensions of the Comparative Exercise . 19 VII. EU Law and the Extracontractual Liability of the European Institutions ................................................................................ 26 VIII. The “Constitutional Traditions Common to the Member States” as an Invitation to Comparative Law ........................... 28 ABSTRACT The European Court of Justice (ECJ) has often been hailed as an engine of European integration. Entrusted with the task of secur- ing the uniform interpretation of the law of the European Union— among other functions—the ECJ makes use of comparative law for a variety of purposes. -

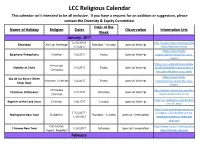

Religious Calendar This Calendar Isn't Intended to Be All Inclusive

LCC Religious Calendar This calendar isn't intended to be all inclusive. If you have a request for an addition or suggestion, please contact the Diversity & Equity Committee. Days of the Name of Holiday Religion Dates Observation Information Link Week January, 2017 12/26/2016 - http://www.history.com/topics/ho Kwanzaa African Heritage Monday - Sunday Special Worship 1/1/2017 lidays/kwanzaa-history https://www.inside- Epiphany/Theophany Christian 1/6/2017 Friday Special Worship mexico.com/ya-vienen-los-reyes- magos/ https://oca.org/saints/lives/2016/ Armenian Nativity of Christ 1/6/2017 Friday Special Worship 12/25/103638-the-nativity-of-our- Orthodox lord-god-and-savior-jesus-christ https://www.inside- Dia de los Reyes (Three Hispanic Christian 1/6/2017 Friday Special Worship mexico.com/ya-vienen-los-reyes- Kings Day) magos/ Orthodox http://www.timeanddate.com/holi Christmas (Orthodox) 1/7/2017 Saturday Special Worship Christian days/russia/christmas-day https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bapt Baptism of the Lord Jesus Christian 1/8/2017 Sunday Special Worship ism_of_Jesus http://www.worldreligionnews.co 1/12/2017 - m/religion-news/buddhism/how- Mahayana New Year Buddhism Thursday - Sunday Special Celebration 1/15/2017 mahayana-buddhists-celebrate- new-year Confucian, http://www.history.com/topics/ho Chinese New Year 1/28/2017 Saturday Special Celebration Daoist, Buddhist lidays/chinese-new-year February http://www.worldreligionnews.co m/religion-news/four-chaplains- Four Chaplains Sunday Interfaith 2/5/2017 Sunday Special Worship sunday-commemorates-priests- -

Holy Days & Holidays Calendar July 1, 2020

HOLY DAYS & HOLIDAYS CALENDAR JULY 1, 2020 – DECEMBER 31, 2021 JULY 2020 AUGUST 2020 SEPTEMBER 2020 OCTOBER 2020 NOVEMBER 2020 DECEMBER 2020 JANUARY 2021 FEBRUARY 2021 MARCH 2021 APRIL 2021 MAY 2021 JUNE 2021 JULY 2021 AUGUST 2021 SEPTEMBER 2021 OCTOBER 2021 NOVEMBER 2021 DECEMBER 2021 S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 1 2 3 4 1 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 1 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 18 19 20 21 22 23 -

2017-2018 Religious Observances Descriptions July 2017 August

2017-2018 Religious Observances Descriptions July 2017 July 4: United States Independence Day also referred to as the Fourth of July, is a federal holiday commemorating the adoption of the Declaration of Independence 241 years ago in 1776 by the Continental Congress. It declared that the thirteen American colonies regarded themselves as a new nation, the United States of America, and were no longer part of the British Empire. July 9: The Martyrdom of the Bab, Baha’is observes the anniversary of the Bab’s execution in Tabriz, Iran, in 1850. July 15: Asalha Puja Day or Dharma Day is a celebration of Buddha’s first teachings. July 23: The birthday of Haile Selassie I, the Emperor of Ethiopia, who the Rastafarians consider to be God and their Savior. July 24: Pioneer Day, observed by the Mormons to commemorate the arrival in 1847 of the first Latter Day Saints pioneer in Salt Lake Valley. August August 1: Tisha B'Av is a fast that commemorates of the destruction of the two holy and sacred Temples of the Jews destroyed by the Babylonians (in 586 B.C.E) and the Romans (in 70 C.E.) and other tragedies of Jewish history. August 6: Transfiguration, a holiday recognized by Orthodox Christians to celebrate when Jesus became radiant, and communed with Moses and Elijah on Mount Tabor. To celebrate, adherents have a feast. August 7: Raksha Bandhan, a Hindu holiday commemorating the loving kinship between a brother and a sister. Raksha means protection in Hindi, and symbolizes the longing a sister has to be protected by her brother. -

Diary of “A Mass of Stones ”: Borobudur in People's

DIARY OF “A MASS OF STONES”: BOROBUDUR IN PEOPLE’S EXPERIENCES YAP BOON HUI B.A. (Hons.), NUS A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2006 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to: the cancer warriors of whom I was a part of. my supervisor, the person with deep humanity -- Dr Jan Mrazek. My heartfelt thanks to you for being such a great mentor, and for helping me rekindle my love for writing. All that you have taught me will remain etched on my mind in this lifetime. Most importantly, thank you so much for successfully “transforming” me from a meek and mild person to an obnoxious and bold creature. Ms Nunuk Rahayu, for her invaluable contribution to my thesis. Professor Reynaldo C. Ileto, who is always encouraging and willing to share with me his personal experiences and knowledge. Thank you for always listening to us intently during lessons, and never failing to respond in the most humorous and intelligent manner. Dr Irving Chan Johnson, whose wit and humour brought so much fun and life to the lectures. Your burning questions always encourage students to think outside the box. Many of us do appreciate you. Professor Goh Beng Lan, who never fails to ask concernedly about the progress of my research work and about my health condition whenever we get to see each other. Professor John Miksic, who is always so kind and patient to help me with my endless enquiries regarding Borobudur and other religious monuments in Indonesia. I am really grateful for your advice and suggestions during the process of my research. -

The Establishment of a Cross-Border Legal Practice in the European Union Florence R

Boston College International and Comparative Law Review Volume 20 | Issue 2 Article 7 8-1-1997 The Establishment of a Cross-Border Legal Practice in the European Union Florence R. Liu Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/iclr Part of the European Law Commons Recommended Citation Florence R. Liu, The Establishment of a Cross-Border Legal Practice in the European Union, 20 B.C. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 369 (1997), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/iclr/vol20/iss2/7 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Establishment of a Cross-Border Legal Practice in the European Union INTRODUCTION Traditionally, lawyers practice law in the country where they com pleted their legal studies. This practice, though still present, is slowly changing in the European Union (EU),! as greater economic integra tion leads to the greater mobility of lawyers.2 EU lawyers benefit from this increased mobility, as they may practice law in a country that is a member of the EU (Member State) in addition to the one where they obtained their legal education and license.3 In practice, this mobility is difficult to achieve because it requires a harmonization of legal standards among countries with different legal systems. 4 The EU's attempts