Factors Affecting the Number of Visits to National Parks in Finland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdfats-2007 -Junior-Ranger-Project

Junior Ranger Project in Europe In partnership to protect Europe’s natural and cultural heritage Report of Study Visits 2008 provided by the Alfred Toepfer Natural Heritage Scholarship 2007, awarded by the EUROPARC Federation and funded by the Alfred Toepfer Foundation F.V.S. of Hamburg, Germany Mgr. Kv ěta Černohlávková [email protected] Czech Republic Acknowledgements Many thanks to the EUROPARC Federation and the Alfred Toepfer Foundation F.V.S. of Hamburg for this outstanding opportunity to visit these protected areas in Europe and to meet all the marvellous people. Thank you for their kind support given to me. Thanks a lot to the Peak District National Park Authority in England. Thanks to Peter Townsend and also to professional rangers Gordon Danks, Terry Page and to the mentor of Youth Rangers Sally Kempson. Many thanks to the Šumava National Park Authority in the Czech Republic. Thanks to the chief of ranger service, Jan Konvi čka, and to the professional ranger Lucie M ěstková. Thanks a lot to the Harz National Park Authority in Germany. Thanks to the coordinator of Junior Ranger Project, Sandra Meckbach-Wolter, and also to professional rangers Bernd Bay, Hermann Zawadski and Alexander Ehrig. Many thanks to the Triglav National Park Authority in Slovenia. Thanks to the chief of ranger service, Martin Šolar, and to the interpretation officer and mountain guide of the Triglav National Park Edvin Kravanja. Many thanks to the Prealpi Giulie Nature Park Authority in Italy. Thanks to the mentor of Junior Rangers, Verdiana Camilla Morandi, and to the nature guide Marco Favalli. -

The Horseshoe of Fennoscandia, Norway, Rein Midteng

The Horseshoe of Fennoscandia-A corridor for the long term survival of old-growth forest dependent species in Norway, Sweden and Finland. Rein Midteng, Asplan Viak. Norway. [email protected] 1.What is the Horseshoe of Fennoskandia? 2. What is its ecologial function? 3. Which subparts does it consist of? 4.Transboundary zones 5. How continuous and broad is the Horseshoe? 6. Key regions and areas in need of protection 7. Futher emphazis Un-protected old-growth forest in Pasvik 1.What is the Horseshoe of Fennoskandia? • Its a more or less continously corridor of old-growth forests from southern Finland/southeast Karealia to southern Norway/Sweden. • It consists of four subparts that are connected as a whole. These four subparts are although presented individually. In addition, it exists so called transboundary zones, which are “green” corridors with mostly continuously old-growth forests that stretch out from the Horseshoe. • Old-growth forests dominate the Horseshoe while in the rest of Fennoscandia culture forests dominate. • It consist of both protected and unprotected old-growth forests. • It includes a great variation of vegetationzones and foresttypes. • It is of major importance in the implementation of the Nagaya goals • It is of major importance for the preservation of old-growth forest species in Norway, Sweden, Finland and probably also in some parts of Russia. 2. What is its (ecologial) function? • It is a migrationzone east-west (since the last ice age), and the Fennoscandinavian countries share therefore to a large extent the same flora and fauna as Russia (low level of endemism). • It provides an exchange of species, individuals and genes to and forth in the Horseshoe. -

FINLAND State of Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture in Finland

COUNTRY REPORT ON THE STATE OF PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE FINLAND State of Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture in Finland Second Finnish National Report Merja Vetel¨ainen M°arten Huld´en Tuula Pehu (compilers) November 6, 2008 Note by FAO This Country Report has been prepared by the national authorities in the context of the preparatory process for the Second Report on the State of World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. The Report is being made available by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as requested by the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. However, the report is solely the responsibility of the national authorities. The information in this report has not been verified by FAO, and the opinions expressed do not necessarily represent the views or policy of FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. CONTENTS ABSTRACT 6 INTRODUCTION TO FINLAND AND ITS AGRICULTURAL SECTOR 7 1. -

Exchange Report

Monthly Activity Log September The start of September is where the orientation activities began. I attend the Aalto party with other UST exchange students and introduced myself to some people in my tutor group. I played games at booths and learnt about the different clubs and societies. With my tutor group I joined Mursujaiset (image on the left)- an event that lasts for 24 hours, the purpose is to officially inaugurate the freshmen (referred to as ‘Mursu’) The day was filled with “interesting” performances, team bonding games and other traditions. Not even sure how to explain the day. I stayed for the first 15 hours and all I can say is that it was a memorable Aalto exchange experience. Even if you can’t stay for the full 24 hours, make sure you’re there for the first 12 hours! I also participated in a 5km run, as someone who is not sporty the run was surprisingly quite fun, and the route was scenic. During the first period (September to Mid-October) I took 3 courses that had quite a heavy workload. The weather is great in September so be sure to go outside and soak up the sun! Sibelius Monument – Mursujaiset 5km Run Aalto Party October After finishing classes from period 1, I had 3 exams that took up the full exam week. During the study break, I went to Oodi Helsinki Library to study, the library is very homey and has amazing interior designs. On the weekend I went with other exchange students to Nuuksio National Park. The national park is closest to the city and is most convenient to get there. -

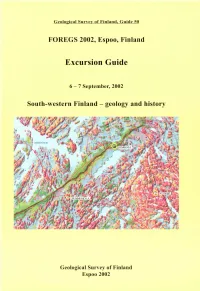

Excursion Guide

Geological Survey of Finland, Guide 50 FOREGS 2002, Espoo, Finland Excursion Guide 6 - 7 September, 2002 South-western Finland - geology and history Geological Survey of Finland Espoo 2002 Geological Survey of Finland, Guide 50 FOREGS 2002, Espoo, Finland Excursion Guide 6-7 September, 2002 South-western Finland - geology and history Geological Survey of Finland Espoo 2002 Geological Survey of Finland, Guide 50 FOREGS 2002, Espoo, Finland Excursion Guide 6-7 September, 2002 South-western Finland - geology and history Compiled by Boris Saltikoff with contributions by Maija Haavisto-Hyvärinen, Matti Saarnisto, Seppo 1. Lahti, Matti Pajunen, Reijo Alviola, Lennart Lauren, Gerhard Hakkarainen, Carl-Göran Sten Geological Survey of Finland Espoo 2002 Boris SaItikoff (comp.) 2002: FOREGS 2002, Excursion Guide 6- 7 September, 2002. South-western Finland - geology and history. Geological Survey of Finland, Guide 50, 32 pages, 22 figures. The publication describes the sights of geological and historical interest along a two-day route in south western Finland, between Helsinki and Parainen. Described are bronze Age cairn in Meilahti, Helsinki, orbicular granitoid occurrence in Nuuksio, Espoo, the Nuuksio National Park, migmatites and the migmatite gneiss in Nummenkylä, Vihti, Salpausselkä end formation, Ojakkala, Vihti, limestone deposit and quarry, Parainen, tantalum pegmatite, Kemiö, Raadesuo peat bog, Kisko, Orijärvi copper mine, Kisko, Fiskars ironworks, Pohja. Abrief description of the geology and history of Finland is given in the introduction. Key words: geology, bedrock, glacial geology, mining industry, history, field trips, guidebook, Uusimaa, Varsinais-Suomi, Finland Boris SaltikojJ Geological Survey 0/ Finland Betonimiehenkuja 4 02150 ESPOO, Finland E-mail: boris.saltikoff@gsUi ISBN 951-690-838-1 ISSN 0781-643X Vamrnalan Kirjapaino Oy 2002 Contents List of illustrations Background - some facts about Finland ... -

Crisis Management in Finnish National Parks

Out of the Woods: Crisis Management in Finnish National Parks Heidi Painilainen Bachelor’s Thesis Degree Programme in Tourism 2011 Abstract Degree programme in tourism Author or authors Group or year Heidi Painilainen of entry Autumn 2007 Title of report Number of Out of the Woods: Crisis Management in Finnish National pages and Parks appendices 56 + 5 Teacher/s or supervisor/s Eva Holmberg, Annika Konttinen The objective of this thesis was to study the crisis management of Finnish national parks. In practice this involves assessing the possible crises that could actually occur in the national parks, how these could be prevented and, finally, what kinds of tools are used for managing these. The theoretical framework of the study introduces crisis management, life-cycle of crisis and national park management. To get a closer look at the national parks, five case studies of different Finnish national parks were conducted. The chosen nation- al parks include Archipelago National Park, Oulanka National Park, Pallas- Yllästunturi National Park, Patvinsuo National Park and Päijänne National Park. These parks were selected since they represent different locations, sizes, environ- mental features and, therefore, also potential crises. The approach of the study is qualitative and the semi-structured interview was cho- sen as the main method of research. A representative of each selected national park was interviewed individually. The interviews resulted in five 29–55 minute recorded conversations which were subsequently transcribed for the purpose of analysis. The interviews were conducted in February 2011 and four of them were executed by Skype due to the long distances. -

CONVENE 2018 Post Fam Tour: Program in Helsinki and Espoo

CONVENE 2018 Post Fam Tour: Program in Helsinki and Espoo Please notice that times/places are subject to change. HELSINKI Helsinki is a dynamic Nordic capital situated on shores of the Baltic Sea. The sea embodies the spirit of Helsinki. The city’s downtown core is surrounded by it; numerous inland bays and channels flow through and define the urban landscape. Helsinki is the centre of Finland’s administrative, educational and cultural life. It is also the finance and business hub of the country. Together with its neighboring cities Helsinki forms the metropolitan area with more than one million inhabitants. The strengths and know-how in the region are based on research, business and innovation. Helsinki is an ideal setting for meetings and incentives: a rich mix, where nature meets urban city life. There are four major conference venues which offer meeting space to small meetings and big conferences of up to 10,000 delegates. The hotel scene offers great locations from design and boutique hotels to large conference hotels. Almost all international hotel brands have presence in Helsinki and most of the hotels are located within 1.5 km from the Main railway station. Activities differ from season to season and tours are available for groups with different interests throughout the year: from guided tours to the design-hungry to snow-mobile and RIB-boat safaris for the adrenaline-driven. If you are posting on social media, please use hashtags: #myhelsinki and #helsinki www.meethelsinki.fi | www.myhelsinki.fi ESPOO The city of Espoo is the second largest and the fastest growing city of Finland – part of the Helsinki Metropolitan Area. -

Last Mile” Project

International benchmarking study about transportation services 28.5.2018 ”Last Mile” Project . The “Last Mile” project (“Perille asti” in Finnish) aims to improve the mobility of local residents and travelers in the Helsinki Region: . Jätkäsaari in Helsinki . Aviapolis and touristic destinations in Vantaa . Nuuksio and Rantaraitti in Espoo . It is a joint project of the city of Vantaa, Espoo Marketing, Forum Virium Helsinki, Metropolia UAS, Aalto University, and Demos Helsinki . ”Last mile” is funded by European Regional Development Fund through the ”Six City Strategy” during 2017-2019 METROPOLIA PROJECT TEAM • Project Manager: Kaija Haapasalo • Project Co-ordinator: Christophe Buyle • Project Assistant: Milka Holmberg • Project Assistant: Valentina Zeljonaja • More information: [email protected] INTRODUCTION TO RESEARCH • This international benchmarking research was done by the project team of Metropolia University of Applied Sciences during January- May 2018 as part of Last Mile project. • The main objective of the research was to provide examples of mobility services implemented or under development in cities and recreational areas similar to the target areas and cities involved in Last Mile project. • In total 41 cases from all over the world were summarized and presented with help of a “Case card”. • The template and content of the “Case card” as well as the main research questions are shown on the following slides. INTRODUCTION TO RESEARCH • Cases were categorized into 4 sub-categories; transportation services, mobility applications, tour packages and other. • The purpose of the research was to provide ideas of possible new mobility services that could be tested and piloted also in Finland e.g. as pilots of the Last Mile project. -

Protecting Finland's Natural Treasures

Metsähallitus Natural Heritage Services Protecting Finland’s natural treasures 1 Natural Heritage Services brings well-being throughout Finland A close relationship with nature is an military use. Vallisaari will become an essential part of the Finnish identity. A attraction for tourists and local residents UBLIC country’s national parks constitute inter- P alongside the nearby World Heritage Site, E nationally important natural heritage R fortress of Suomenlinna. – places that we can be proud of, and 2013 was also a busy and productive show off to our visitors. Our parks have year for Natural Heritage Services in our been created both to conserve nature more established fields. We prepared and to benefit people, by providing reports for the Ministry of the Environ- amenities that promote health, enhance ment about prospects for setting up well-being and strengthen our respect new national parks. Hunters and fishers FFICE OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE for nature and our links with nature. O have been able to use our webservice to purchase permits more easily than ever he increasing unfamiliarity of urban PHOTO: before. We have also expanded our work residents with nature, and particu- evaluating the ecological state of the T larly the gradual loss of a connec- The new Finnish Nature Centre Haltia was Baltic Sea, surveying extensive areas of tion with nature evident among children officially opened by the President of Finland the sea bed. Progress has also been made and young people in the Helsinki area, Sauli Niinistö and his wife Jenni Haukio. on major EU-funded projects promoting are worrying social trends. -

Sustainable Tourism Development Strategy for Oulanka National Park 2011

istio Sari Alatossava Sustainable Tourism Development Strategy for Oulanka National Park 2011 Metsähallituksen luonnonsuojelujulkaisuja. Sarja C 112 Nature Protection Publications of Metsähallitus. Series C 112 Sari Alatossava Metsähallitus Natural Heritage Services, Ostrobothnia PO Box 26 93601 Kuusamo, Finland [email protected] Translated by Fran Weaver Översättning: Firma Pimma Åhman Cover photo: Oulanka’s suspension bridges lead visitors into a world of unforgettable experiences. Photo: Mylene van der Donk © Metsähallitus 2011 ISSN-L 1796-2943 ISSN 1796-2943 (online) ISBN 978-952-446-916-6 (pdf) Sari Alatossava Sustainable Tourism Development Strategy for Oulanka National Park 2011 DOCUMENTATION PAGE PUBLISHED BY Metsähallitus PUBLICATION DATE 5.8.2011 COMMISSIONED BY Metsähallitus DATE OF APPROVAL 23.2.2011 CONFIDENTIALITY Public REGISTRATION NO. 1504/530/2011 TYPE OF PROTECTED National Park, Natura 2000 Site AREA/CONSERVATION PROGRAMME NAME(S) OF PROTECTED Oulanka National Park AREA(S) NATURA 2000 SITE Oulanka FI1101645 NAME(S) AND CODE(S) REGIONAL UNIT Natural Heritage Services, Ostrobothnia AUTHOR(S) Sari Alatossava TITLE Sustainable Tourism Development Strategy for Oulanka National Park 2011 ABSTRACT Oulanka National Park is located in a region of NE Finland that is important for tourism, midway between the tourism centres of Ruka-Kuusamo and Salla. Thanks to its unique natural features, diverse facilities, and a long history and strong image as a destination for hiking and outdoor activi- ties, the park is popular both in terms of visitor numbers and as a regional tourist attraction. The park welcomes almost 170,000 visitors annually. Visitors’ spending boosted the local economy by an estimated 15 million euros in 2010. -

Enchanting Arctic Experiences Since 1974

KAKSLAUTTANEN ARCTIC RESORT – ENCHANTING ARCTIC EXPERIENCES SINCE 1974. Kakslauttanen Arctic Resort Kiilopääntie 9, 99830 Saariselkä, Finland Closest airport: Ivalo (IVL) Open year round (except during May) Take a virtual tour Winter/Spring video – Summer/Autumn video - www.kakslauttanen.fi Follow us Facebook - Instagram - Twitter - Pinterest – YouTube Facebook & Twitter: @kakslauttanen Instagram: @kakslauttanen_arctic_resort #kakslauttanen Image bank http://kakslauttanen.kuvat.fi/kuvat/ password: welcome2lauttanen Thank you for crediting Kakslauttanen Arctic Resort. If possible, please include a link to our website www.kakslauttanen.fi and note that for some images the photographer should be credited too. ENCHANTING ARCTIC EXPERIENCES SINCE 1974 Kakslauttanen Arctic Resort is an enchanting, otherworldly destination located 250 kilometres (150 miles) north of the Arctic Circle in Finnish Lapland, just a four-hour drive from the Arctic Ocean. Since 1974, our family-run hotel has been offering year-round magical experiences in the pristine arctic wilderness. We are world-renowned for our iconic Glass Igloos and the magical Northern Lights – but there are plenty of other arctic secrets to explore. We offer numerous unique excursions – from reindeer and husky adventures to meeting Santa or panning for gold – making any stay truly unforgettable. You will be surrounded by some of the cleanest nature in the world, with one of Finland's largest national parks, Urho Kekkonen National Park, right next door. The water is so pure that you can drink straight from the streams, the air is so fresh that you can feel it deep down in your lungs, and the harmonious sound of silence will soothe your soul. The region is steeped in the rich culture of the indigenous Sámi people. -

Aurora Alarm System

KAKSLAUTTANEN ARCTIC RESORT – ENCHANTING ARCTIC EXPERIENCES SINCE 1974. Kakslauttanen Arctic Resort Kiilopääntie 9, 99830 Saariselkä, Finland Closest airport: Ivalo (IVL) Open year round (except during May) Take a virtual tour Winter/Spring video – Summer/Autumn video - www.kakslauttanen.fi Follow us Facebook - Instagram - Twitter - Pinterest – YouTube Facebook & Twitter: @kakslauttanen Instagram: @kakslauttanen_arctic_resort #kakslauttanen Image bank http://kakslauttanen.kuvat.fi/kuvat/ password: Visit_Kakslauttanen_Media_2018 Thank you for crediting Kakslauttanen Arctic Resort. If possible, please include a link to our website www.kakslauttanen.fi and note that for some images the photographer should be credited too. ENCHANTING ARCTIC EXPERIENCES SINCE 1974 Kakslauttanen Arctic Resort is an enchanting, otherworldly destination located 250 kilometres (150 miles) north of the Arctic Circle in Finnish Lapland, just a four-hour drive from the Arctic Ocean. Since 1974, our family-run hotel has been offering year-round magical experiences in the pristine arctic wilderness. We are world-renowned for our iconic Glass Igloos and the magical Northern Lights – but there are plenty of other arctic secrets to explore. We offer numerous unique excursions – from reindeer and husky adventures to meeting Santa or panning for gold – making any stay truly unforgettable. You will be surrounded by some of the cleanest nature in the world, with one of Finland's largest national parks, Urho Kekkonen National Park, right next door. The water is so pure that you can drink straight from the streams, the air is so fresh that you can feel it deep down in your lungs, and the harmonious sound of silence will soothe your soul. The region is steeped in the rich culture of the indigenous Sámi people.