Restricted CO M/TD/ENV (97)10/F in a L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extensions of Remarks 4683

February 26, 1976 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 4683 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS . ' .. WILLIAM ODIE WRIGHT-SUPER longs to the California Heights Com In essence, Nat Wasserman is the vol· INTENDENT OF SCHOOLS · munity Church of Long Beach. unteers' volunteer. Wherever there is a For many years, Odie Wright has peen need stemming from the lack of action identified as an integral member of the by society-wherever there is a need of HON. GLENN M. ANDERSON Long Beach community. His many yea1·s people who cannot help themselves be of service saw the Long Beach Unified cause of ignorance of the system, Nat OF CALIFORNIA School District grow and develop into Wasserman becomes his own total social IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES the outstanding institution it is today. welfare agency, seeking solutions, coun Thursday, February 26, 1976 Odie Wright's knowledge and experience seling the troubled. in the educational world will be missed. His interest in the welfare of others Mr. ANDERSON of California. Mr. has helped many people to lead happier, Speaker, at the conclusion of this school My wife Lee joins me in congratulating year the Long Beach Unified School Dis Odie Wright on a highly productive ca more productive lives. His optimism af trict will lose the leadership of a man reer, and in wishing him a well-earned fects all those who are touched by his rest in retirement. presence. His persistence is a trait that who has devoted his entire life to edu His lovely wife, Ruth, and their child typifies his effectiveness. cation. William Odie Wright, superin I feel that the people of Stamford have tendent of schools, will retire this sum ren, Virginia Wilky, Barbie, and Jerry, mer. -

Reservations Entered by Parties in Effect from 9 October 2013

CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA Reservations entered by Parties in effect from 26 November 2019 Appendices I and II ORDER / Family Species Country In effect from All amendments adopted at the 18th meeting of the Conference of the Canada 26/11/2019 Parties Appendix I ORDER / Family Species Country In effect from F A U N A (A N I M A L S) P H Y L U M C H O R D A T A CLASS MAMMALIA (MAMMALS) CARNIVORA Canidae Canis lupus North Macedonia 02/10/2000 Dogs, foxes, wolves (Only the populations of Bhutan, India, Nepal and Pakistan; all other populations are included in Appendix II. Excludes the domesticated form and the dingo which are referenced as Canis lupus familiaris and Canis lupus dingo, respectively, which are not subject to the provisions of the Convention) Felidae Acinonyx jubatus Namibia 18/03/1991 Cats CETACEA Dolphins, porpoises, whales Balaenopteridae Balaenoptera acutorostrata Iceland 02/04/2000 Fin whales, humpback (except the population of West Greenland, Japan 01/01/1986 whales, rorquals which is included in Appendix II) Norway 01/01/1986 Palau 15/07/2004 Balaenoptera bonaerensis Iceland 02/04/2000 Japan 01/01/1986 Norway 01/01/1986 Balaenoptera borealis Iceland 02/04/2000 Balaenoptera borealis Japan 06/06/1981 [reservation not applicable to populations: Norway 06/06/1981 a) in North Pacific; and b) in areas from 0 to 70 degrees east longitude and from the equator to the Antarctic Continent] Balaenoptera edeni Japan 29/07/1983 Balaenoptera musculus Iceland 02/04/2000 Balaenoptera -

After the Fall

SWEDEN After the Fall Nowhere in the world has the dream of reason been pursued quite so vigorously as in the Kingdom of Sweden. Under Social Democratic leadership, this Scandinavian country became famous around the world for its humane “Middle Way.” Swedes believed that their distinctive “Swedish model,” with its massive welfare state, its near-full employ- ment, and its lofty egalitarianism, provided at least a glimpse of what a rationally con- structed utopia might be. In recent years, however, the Swedish model has developed serious problems, and Swedes have begun to ponder some profoundly unsettling ques- tions—questions about who they are and where they are headed. Our author takes us to post-utopian Sweden. by Gordon F. Sander ever say that Swedes have no religion. That is a myth. They do indeed—although it is not Lutheranism, which is no longer even the estab- lished religion, since church and state were finally separated this year after four centuries of official union. Moreover, although 87 percent of Swedes Nnominally belong to the Lutheran Evangelical Church, attendance at ser- vices has long been pitifully low. Not so with Sweden’s true religion, the one in which virtually all Swedes participate. That religion is devoted to the worship of sommar. Sommar: that sweet, intense, yet poignantly short season from mid-June through mid-August when seemingly all nine million Swedes close up shop and head upcountry, or to one of the myriad islands or archipelagoes surrounding this narrow landmass on the Baltic Sea, to savor the long blue days and brief “white nights” at their rustic vacation cottages. -

Saker Falcon Falco Cherrug Global Action Plan (Sakergap)

CMS RAPTORS MOU TECHNICAL PUBLICATION NO. 2 CMS TECHNICAL SERIES NO. 31 Saker Falcon Falco cherrug Global Action Plan (SakerGAP) including a management and monitoring system, to conserve the species The Coordinating Unit of the Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Birds of Prey in Africa and Eurasia (Raptors MOU) Saker Falcon Task Force Saker Falcon Falco cherrug Global Action Plan (SakerGAP) including a management and monitoring system, to conserve the species Prepared with financial contributions from the Environment Agency - Abu Dhabi on behalf of the Government of the United Arab Emirates, the Saudi Wildlife Authority on behalf of the Government of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the European Commission on behalf of the European Union, the Secretariat of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora and the Parties to the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. CMS Raptors MOU Technical Publication No. 2 CMS Technical Series No. 31 August 2014 Saker Falcon Falco cherrug Global Action Plan (SakerGAP), including a management and monitoring system, to conserve the species. The SakerGAP was commissioned by the Saker Falcon Task Force, under the auspices of the CMS Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Birds of Prey in Africa and Eurasia (Raptors MOU). The preparation of the plan was financially supported by the Environment Agency - Abu Dhabi on behalf of the Government of the United Arab Emirates, the Saudi Wildlife Authority on behalf of the Government of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the Environment and Sustainable Management of Natural Resources (ENRTP) Strategic Cooperation Agreement (STA) between the European Commission – Directorate-General (DG) for the Environment – and UNEP, the Secretariat of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and the Parties to the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). -

Out of Africa? Phylogenetic Relationships Between Falco Biarmicus and the Other Hierofalcons (Aves: Falconidae)

Ó 2005 Blackwell Verlag, Berlin Accepted on 24 June 2005 JZS doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0469.2005.00326.321–331 1Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Museum of Natural History Vienna, Vienna, Austria; 2Institute of Pharmacy and Molecular Biotechnology, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany Out of Africa? Phylogenetic relationships between Falco biarmicus and the other hierofalcons (Aves: Falconidae) F. Nittinger1,E.Haring1,W.Pinsker1,M.Wink2 and A. Gamauf1 Abstract The phylogeographic history of the lanner falcon (Falco biarmicus) and the phylogenetic relationships among hierofalcons (F. biarmicus, Falco cherrug, Falco jugger and Falco rusticolus) were investigated using mitochondrial (mt) DNA sequences. Of the two non-coding mt sections tested, the control region (CR) appeared more suitable as phylogenetic marker sequence compared with the pseudo control region (WCR). For the comprehensive analysis samples from a broad geographic range representing all four hierofalcon species and their currently recognized subspecies were included. Moreover, samples of Falco mexicanus were analysed to elucidate its phylogenetic relationships to the hierofalcons. The sequence data indicate that this species is more closely related to Falco peregrinus than to the hierofalcons. In the DNA-based trees and in the maximum parsimony network all hierofalcons appear closely related and none of the species represents a monophyletic group. The close relationships among haplotypes suggest that the hierofalcon complex is an assemblage of morphospecies not yet differentiated in the genetic markers used in the present study and that the radiation of the four hierofalcon species took place rather recently. Based on the high intraspecific diversity found within F. biarmicus we assume an African origin of the hierofalcon complex. -

Extens:Ions of Remarks Mr

23888 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS July 26, 1976 The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without the Soviet Union's lllegal annexation of usual form; that there be a time limita objection, it is so ordered. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and tion on any other amendment, debatable Whereas, although neither the President Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. President, nor the Department of State issued a specific motion, appeal, or point of order, if such I suggest the absence of a quorum. disclaime- in conjunction With the signing be submitted to the Senate, of 10 min The PRESIDING OFFICER. The clerk of the Final Act a.t Helsinki to make clear utes; and that the agreement be in the will call the roll. that the United States still does not recog usual form, with the exception of the The second assistant legislative clerk nize the forcible conquest of those nations amendment by Mr. BUCKLEY, for which proceeded to call the roll. by the Soviet Union, both the President in provisions already have been entered. Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. President, his public statement of July 25, 1975, and The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without I ask unanimous consent that the order the Assistant Secretary of State for European objection, it is so ordered. Affairs in his testimony before the Subcom for the quorum call be rescinded. mittee on International Political and Mlli The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without tary Affairs of the House Committee on In objection, is is so ordered. ternational Relations stated quite explicitly PROGRAM that the longstanding official policy of the United States on nonrecognition of the Mr. -

A Global Update on Lead Poisoning in Terrestrial Birds

A GLOBAL UPDATE OF LEAD POISONING IN TERRESTRIAL BIRDS FROM AMMUNITION SOURCES 1 2 3 DEBORAH J. PAIN , IAN J. FISHER , AND VERNON G. THOMAS 1Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge, Gloucestershire, GL2 7BT, UK E-mail: [email protected] 2Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire SG19 2DL, UK 3Department of Integrative Biology, College of Biological Science, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON N1G 2W1, Canada. ABSTRACT.—Lead poisoning mortality, through the ingestion of spent shot, is long established in water- fowl, and more recently in raptors and other avian taxa. Raptors (vultures, hawks, falcons, eagles and owls) are exposed to lead from spent ammunition (shot, bullets, or fragments from either) while feeding on game species, and other avian taxa are exposed when feeding in shot-over areas, including shooting ranges. Here we review the published literature on ingestion of and poisoning by lead from ammunition in terrestrial birds. We briefly discuss methods of evaluating exposure to and poisoning from ammunition sources of lead, and the use of lead isotopes for confirming the source of lead. Documented cases include 33 raptor species and 30 species from Gruiformes, Galliformes and various other avian taxa, including ten Globally Threatened or Near Threatened species. Lead poisoning is of particular conservation concern in long-lived slow breeding species, especially those with initially small populations such as the five Globally Threat- ened and one Near Threatened raptor species reported as poisoned by lead ammunition in the wild. Lead poisoning in raptors and other terrestrial species will not be eliminated until all lead gunshot and rifle bul- lets are replaced by non-toxic alternatives. -

THE GLOBALIZATION of College and University Rankings by Philip G

THE GLOBALIZATION OF College and University Rankings By Philip G. Altbach Philip G. Altbach ([email protected]) is Monan professor of higher education and director of the Center for International Higher Education at Boston College. 26 Change • January/February 2012 n the era of globalization, accountability, and bench- intended to be used, as it has been, for ranking purposes. The marking, university rankings have achieved a kind of German methodology permits users to select specific vari- THE GLOBALIZATION OF iconic status. The major ones—the Academic Ranking ables and develop their own groupings, just as the Carnegie of World Universities (ARWU, or the “Shanghai rank- Classification now allows users to “create a customized list ings”), the QS (Quacquarelli Symonds Limited) World of institutions.” IUniversity Rankings, and the Times Higher Education World If rankings did not exist, someone would have to invent University Rankings (THE)—are newsworthy across the them. They are an inevitable result of higher education’s world. In this nation, the US News & World Report’s influ- worldwide massification, which produced a diversified and ential and widely criticized ranking of America’s colleges complex academic environment, as well as competition and College and and universities, now in its 17th year, creates media buzz commercialization within it. It is not surprising that rankings every year—who is “up” and who is “down”? Indeed, most became prominent first in the United States, the country that of the national rankings are sponsored by magazines or other developed mass higher education the earliest. media outlets: US News in the United States, Maclean’s So who uses these rankings and for what purposes? What in Canada, Der Spiegel in Germany, the Asahi Shimbun in problems do the systems have, and what is the nature of the Japan, the Good University Guide in the United Kingdom, debate that currently swirls around each of them? University Perspektywy in Poland, and numerous others worldwide. -

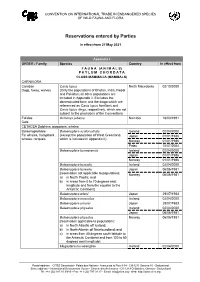

Reservations Entered by Parties

CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA Reservations entered by Parties in effect from 27 May 2021 Appendix I ORDER / Family Species Country In effect from F A U N A (A N I M A L S) P H Y L U M C H O R D A T A CLASS MAMMALIA (MAMMALS) CARNIVORA Canidae Canis lupus North Macedonia 02/10/2000 Dogs, foxes, wolves (Only the populations of Bhutan, India, Nepal and Pakistan; all other populations are included in Appendix II. Excludes the domesticated form and the dingo which are referenced as Canis lupus familiaris and Canis lupus dingo, respectively, which are not subject to the provisions of the Convention) Felidae Acinonyx jubatus Namibia 18/03/1991 Cats CETACEA Dolphins, porpoises, whales Balaenopteridae Balaenoptera acutorostrata Iceland 02/04/2000 Fin whales, humpback (except the population of West Greenland, Japan 01/01/1986 whales, rorquals which is included in Appendix II) Norway 01/01/1986 Palau 15/07/2004 Balaenoptera bonaerensis Iceland 02/04/2000 Japan 01/01/1986 Norway 01/01/1986 Balaenoptera borealis Iceland 02/04/2000 Balaenoptera borealis Japan 06/06/1981 [reservation not applicable to populations: Norway 06/06/1981 a) in North Pacific; and b) in areas from 0 to 70 degrees east longitude and from the equator to the Antarctic Continent] Balaenoptera edeni Japan 29/07/1983 Balaenoptera musculus Iceland 02/04/2000 Balaenoptera omurai Japan 29/07/1983 Balaenoptera physalus Iceland 02/04/2000 Japan 06/06/1981 Balaenoptera physalus Norway 06/06/1981 [reservation applicable to populations: a) -

JANUARY Is the First Month in the Modern Calendar and Has 31 Days

JANUARY is the first month in the modern calendar and has 31 days. Although the days have begun to grow longer by this point dur- ing the year, the temperature in the Northern Hemisphere continues to fall, making January one of the coldest, most oppressive months of the year. In 1853 the Russian emperor Nicholas I said, “Russia has two generals in whom she can con- fide—January and February,” referring to the bru- tal winter months which have frequently defended the country against invaders. The name (Januar- ius in Latin) is derived from the two-faced Roman god Janus, who is simultaneously looking forward and backward. Some scholars have claimed that the name Janus is from the Latin ianua, meaning door, while others have explained it as the mascu- line form of Diana, which would be Dianus or Ianus. There are many conflicting theories about Janus and his role in the Roman religion. He apparently figured prominently as the god of all beginnings, watching over gates and doorways and presiding over the first hour of the day, the first day of the month, and the first month of the year. His name was invoked at the start of important undertakings, perhaps with the idea that his intervention as the “janitor” of all avenues would speed prayers directly to the immor- tals. Janus was also entitled Consivius, or sower, in reference to his role as the beginner or orig- inator of agriculture. As the animistic spirit of doorways (ianuae) and arches (iani), Janus guarded the numerous ceremonial gateways in Rome.