Masters Thesis D. Gex-Collet-The Peril of Voice Seeking in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aalborg Universitet Restructuring State and Society Ethnic

Aalborg Universitet Restructuring State and Society Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia Balcha, Berhanu Publication date: 2007 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Balcha, B. (2007). Restructuring State and Society: Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia. SPIRIT. Spirit PhD Series No. 8 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: November 29, 2020 SPIRIT Doctoral Programme Aalborg University Kroghstraede 3-3.237 DK-9220 Aalborg East Phone: +45 9940 9810 Mail: [email protected] Restructuring State and Society: Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia Berhanu Gutema Balcha SPIRIT PhD Series Thesis no. 8 ISSN: 1903-7783 © 2007 Berhanu Gutema Balcha Restructuring State and Society: Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia SPIRIT – Doctoral Programme Aalborg University Denmark SPIRIT PhD Series Thesis no. -

The Case of Indigenous People in State of Benishangul Gumuz

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Culture, Society and Development www.iiste.org ISSN 2422-8400 An International Peer-reviewed Journal DOI: 10.7176/JCSD Vol.47, 2019 An Investigation on the Consequences of Mal-traditional Practices: The Case of Indigenous People in State of Benishangul Gumuz Shewa Basizew M.Ed in English as a foreign language Abebe Ano Assistant Professor of History and Phd candidate Atnafu Morka Assistant Professor in Geography and Environmental Study Abstract In today's Ethiopia where challenges on development is made by indigenous people in regions, State of Benishangul Gumuz region is extending its effort towards reaching excellence in all aspects including health and societal matters. As part of the country's effort, Benishangul Gumuz region in general and Assosa University in particular carries out various studies based on scientific plans for scaling up its achievements constantly. However, Mal-traditional practices (MTP's)–Festival Ceremony, marriage related practices (early marriage, Abduction marriage, Bride wealth payment and inheritance marriage), domestic violence and skin cutting) are the most prevalence and challenge phenomena among indigenous people of the region. Thus, this study was aimed at assessing on the effects of mal-traditional practices among indigenous people in State of Benishangul- Gumuz Region. In doing so, the study particularly attempted to examine the level (prevalence) and impact of these mal-traditional practices on socio-economic and health conditions of indigenous people in study areas. To identify the factors hindering government officials in eliminating mal-traditional practices among the indigenous people in the region. -

Wherein Lies the Equilibrium in Political Empowerment? Regional Autonomy Versus Adequate Political Representation in the Benishangul Gumuz Region of Ethiopia

ACTA HUMANA • 2015/Special edition 31–51. Wherein Lies the Equilibrium in Political Empowerment? Regional Autonomy versus adequate Political Representation in the Benishangul Gumuz Region of Ethiopia BEZA DESSALEGN* After the implementation of the post 1991 EPRDF government’s program of ethnic re- gionalism, local ethnic rivalries have intensified among indigenous nationalities and non-indigenous communities of Benishangul Gumuz. The quest for regional autono- my of the indigenous nationalities, especially, to profess their need of self-rule, did not resonate very well with the political representation rights of the non-indigenous com- munities. In this regard, the paper argues that the problem is mainly attributable to the fact that the Constitutional guarantees provided under the FDRE Constitution have not been seriously and positively implemented to bring about a balanced polit- ical empowerment. Making the matter even worse, the regional state’s Constitution placement of a Constitutional guarantee by which the indigenous nationalities are considered to be the ‘owners’ of the regional state coupled with an exclusionary po- litical practice, relegating others to a second-class citizenship, has undermined the notion of “unity in diversity” in the region. Thus, striking a delicate balance between the ambitions of the indigenous nationalities regional autonomy on the one hand and extending adequate share of the regions political power to the non-indigenous communities on the other is a prerequisite for a balanced political empowerment. 1. Introduction Benishangul Gumuz is one of the nine federated states of the Ethiopian federation. It has a total area of 50,380 square kilometers with a population size of 670,847 inhabit- ants.1 It is administratively divided into three zones of Assosa, Metekel and Kamashi. -

Assosa - Guba Road Project Public Disclosure Authorized

RPi 36 V/olume 9 Ethiopian Roads Authority (ERA) Public Disclosure Authorized Resettlement Action Plan Assosa - Guba Road Project Public Disclosure Authorized Final Report SCANNE Dte FLEL,QPYRaC ccLONa ACC8SSi;r l Public Disclosure Authorized NF iS older March 2004 Carl Transport Bro als Department Carl Public Disclosure Authorized IntelligentBro 6^ Solutions FILE tt Carl Bro 46 International Development Agency Intelligent Solutons 1 81 8th Street r 5 n ms nrl I Water &Environment Washington DC 20433 rl - - . l Industryd&uMarine USA.s 04 ,gnC d IT& Telecommunicaton Management Attn: Mr. John Riverson - Building Lead Highway Engineer Transportation AFTTR Energy Addis Ababa Agrculture Ethiopia 05 March 2004 Job No. 80.1959. 06 Letter No. IDA -41 1 Ref.: Assosa - Guba Road Project Resettlement Action Plan Dear Sir, As per ERA's letter of February 27, 2004 regarding the finalization of the RAP Report, we have the pleasure in submitting two (2) copies of the Draft Final Report for your pe- rusal. Yours faithfully, ; carl3 ercr > r ,1-fS olt t itan l * 15, Y, _ ^ Henrik M. Jeppesen Project Manager SCANNED FILE COPY .rr - {c-dJ lI 1 - ______ ..:s.)inet/Drawer/Folder/Sub10oder. TransQrtation F e3 Con 6 Tran.sportafi o nCons~ultinq Fnqineers Assosa - Guba Road Project Resettlement Action Plan Distribution List DISTRIBUTION LIST Sent to: Number of Copies Ethiopian Roads Authority P.O. Box 1770 Addis Ababa Ethiopia 4 Tel: (251-1) 15 66 03 Fax: (251-1) 51 48 66 Telex 21180 Att.: Ato Zaid Woldegabriel International Development Agency 1818H Street 2 Washington DC. 20433 U.S.A. -

Postponed Local Concerns?

Postponed Local Concerns? Implications of Land Acquisitions for Indigenous Local Communities in BenishangulGumuz Regional State, Ethiopia. Tsegaye Moreda LDPI Working Paper Postponed Local Concerns? Implications of Land Acquisitions for Indigenous Local Communities in Benishangul‐Gumuz Regional State, Ethiopia. by Tsegaye Moreda Published by: The Land Deal Politics Initiative www.iss.nl/ldpi [email protected] in collaboration with: Institute for Development Studies (IDS) University of Sussex Library Road Brighton, BN1 9RE United Kingdom Tel: +44 1273 606261 Fax: +44 1273 621202 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ids.ac.uk Initiatives in Critical Agrarian Studies (ICAS) International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) P.O. Box 29776 2502 LT The Hague The Netherlands Tel: +31 70 426 0664 Fax: +31 70 426 0799 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.iss.nl/icas The Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) School of Government, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17 Bellville 7535, Cape Town South Africa Tel: +27 21 959 3733 Fax: +27 21 959 3732 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.plaas.org.za The Polson Institute for Global Development Department of Development Sociology Cornell University 133 Warren Hall Ithaca NY 14853 United States of America Tel: +1 607 255-3163 Fax: +1 607 254-2896 E-mail: [email protected] Website: polson.cals.cornell.edu © February 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher and the author. -

Alternative Citizenship the Nuer Between Ethiopia and the Sudan ABORNE Workshop on Sudan’S Borders, April 2011 Dereje Feyissa

Alternative citizenship The Nuer between Ethiopia and the Sudan ABORNE Workshop on Sudan’s Borders, April 2011 Dereje Feyissa Abstract A lot has been written about state borders as constraints to local populations who are often ‘artificially’ split into two and at times more national states (Asiwaju 1985; Kolossov 2005). The Nuer, like many other pastoral communities arbitrarily divided by a state border, have experienced the Ethio-Sudanese border as a constraint, in as much as they were cut off from wet season villages in the Sudan and dry season camps in Ethiopia. As recent literature on the border has shown, however, state borders function not only as constraints but also as opportunities (Nugent 2002), and even as ‘resources’ (Dereje and Hohene 2010). The paper examines how the Nuer have positively signified state border by tapping into - taking advantage of their cross-border settlements -fluctuating opportunity structures within the Ethiopian and Sudanese states through alternative citizenship. Nuer strategic action is reinforced by a flexible identity system within which border-crossing is a norm. Sudan's Southeastern frontier: The Toposa and their Neighbours (abstract) The Topòsa and some of their neighbours have long been among the groups in particular remoteness from the political and economic metabolism of the state system. Until recently, the borders of the Sudan with three other nations, Uganda, Kenya and Ethiopia, that touch on their area could be considered mere notions and lines on maps of another world. This situation has substantially changed since the 2nd Sudanese Civil War – and with it the meaning of terms like “their area”. -

Aalborg Universitet Restructuring State and Society Balcha, Berhanu

Aalborg Universitet Restructuring State and Society Balcha, Berhanu Publication date: 2007 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Balcha, B. (2007). Restructuring State and Society: Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia. Aalborg: SPIRIT. Spirit PhD Series, No. 8 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: januar 09, 2019 SPIRIT Doctoral Programme Aalborg University Kroghstraede 3-3.237 DK-9220 Aalborg East Phone: +45 9940 9810 Mail: [email protected] Restructuring State and Society: Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia Berhanu Gutema Balcha SPIRIT PhD Series Thesis no. 8 ISSN: 1903-7783 © 2007 Berhanu Gutema Balcha Restructuring State and Society: Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia SPIRIT – Doctoral Programme Aalborg University Denmark SPIRIT PhD Series Thesis no. 8 ISSN 1903-7783 Published by SPIRIT & Department of Culture and Global Studies Aalborg University Distribution Download as PDF on http://spirit.ihis.aau.dk/ Front page lay-out Cirkeline Kappel The Secretariat SPIRIT Kroghstraede 3, room 3.237 Aalborg University DK-9220 Aalborg East Denmark Tel. -

Federalism and Conflict Management in Ethiopia

Federalism and Conflict Management in Ethiopia. Case Study of Benishangul-Gumuz Regional State. Item Type Thesis Authors Gebremichael, Mesfin Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 27/09/2021 18:40:17 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/5388 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Federalism and Conflict Management in Ethiopia: Case Study of Benishangul-Gumuz Regional State Mesfin Gebremichael PhD 2011 Federalism and Conflict Management in Ethiopia: Case Study of Benishangul-Gumuz Regional State Mesfin Gebremichael Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Peace Studies University of Bradford September 2011 Abstract In 1994 Ethiopia introduced a federal system of government as a national level approach to intra-state conflict management. Homogenisation of cultures and languages by the earlier regimes led to the emergence of ethno-national movements and civil wars that culminated in the collapse of the unitary state in 1991. For this reason, the federal system that recognises ethnic groups‟ rights is the first step in transforming the structural causes of civil wars in Ethiopia. -

Country Profiles Are Produced by the Department of State's Bureau Of

iRELEASED IN FULLj Bur•• u of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor ETHIOP~ ASYLUM COUNTRY PROFILE August 2007 ([EVIEINAUTHORITY: Archie Bolster, Senior Reviewe~ I. INTRODUCTION country profiles are produced by the Department of State's Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, Office of Multilateral and Global Affairs for use by the Executive Office of Immigration Review and the Department of Homeland Security in assessing asylum claims. By regulation, the Department of State may provide asylum officers and inunigration judges informa-tion on country conditions that may be pertinent to the adjudication of asylum claims. The purpose of this and other profiles is to provide factual information relating to such conditions. They do not relate to particular asylum claims, but provide general country condition information as of the date they are drafted .. They are written by State Department officers with expertise in the relevant area and are circulated for comment within the Department) including to overseas missions. This country profile focuses on the issues most frequently raised by Ethiopian asylum applicants and the regions from which most applicants come. It cannot cover every conceivable circumstance asylum applicants may raise, nor does it address conditions in every region in Ethiopia, where local enforcement of national policies is often uneven. Adjudicators may wish to consult the latest versions of ~he Department of State 1 s annual Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, International Religious Freedom Report, and Trafficking In Persons Report, all of which are availabl.e on the Internet at w;]w.state.gov, and other publicly available material on conditions in Et:hiopia. -

Feasibility Study and Environmental Impact Assessment For: Assosa

E698 Volume 3 Ethiopian Roads Authority (ERA) Public Disclosure Authorized Feasibility Study and Environmental Impact Assessment for: Public Disclosure Authorized Assosa - Guba Road Project (NDF Credit No. 207-TD1) Final Environmental Impact Assessment Public Disclosure Authorized SCANNED FILE COPY J::KM Date -N 1. 0 I R L ! _ Action cc~ Accsion No. tox No. Cabinet/Drawer/Folder/Subfolder: November 2001 6oOOC-o 0 Carl Bro a/s 2 Transport Department Public Disclosure Authorized _ in association with DANA Consult Plc o0 Engineering Consultants Assosa - Guba Road Project Phase 1: Feasibility and EIA Study Distribution DISTRIBUTION LIST Sent to: Recommended to receive a Number of review copy Copies _Ethiopian Roads Authoaty * ERA Environmental P.O. Box 1770 Management Branch pAddisAbaba The Regional Environmental Ethiopia Coordinating Committee of Tel: (251-1) 15 66 03 Benishangul-Gumuz Bureau Fax: (251-1) 51 48 66 of Planning and Economic 5 _Telex 21180 Development Att.: Ato Tesfamichael Nahusenay * Ethiopia Environmental _ Protection Agency * Authority for Research and Conservation of Cultural Heritage Intemational Development Association 1818H Street 2 Washington DC. 20433 U.S.A. Fax: (202) 473-8326 Carl Bro a/s Granskoven 8 2600 Glostrup 1 Denmark Tel: and45 43 96 80 11 Fax: and45 43 96 85 80 Att.: Jan Lorange Assosa - Guba Road Project Phase 1: Feasibility and EIA Study Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 6 1. INTRODUCTION 19 1.1 Background 19 1.2 Objectives of the Environmental Study 19 1.3 EIA Approach and Methodology 20 1.4 Project Route References 21 2. INSTITUTIONAL AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK 23 2.1 Environmental Protection and Management at National Level 23 2.2 Environmental Impact Assessment 23 2.3 Classification of the Assosa-Guba Road Project 24 2.4 Environmental Management in the Roads Sector 25 2.5 Regional Policies on Environment 25 3. -

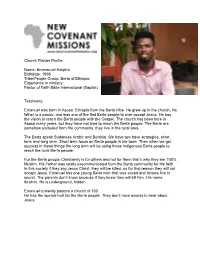

Emmanuel Kalipha Birthdate: 1995 Tribe/People Group: Berta of Ethiopia Experience in Ministry: Pastor of Faith Bible International (Baptist)

Church Planter Profile Name: Emmanuel Kalipha Birthdate: 1995 Tribe/People Group: Berta of Ethiopia Experience in ministry: Pastor of Faith Bible International (Baptist) Testimony: Emanuel was born in Asosa, Ethiopia from the Berta tribe. He grew up in the church, his father is a pastor, and was one of the first Berta people to ever accept Jesus. He has the vision to reach the Berta people with the Gospel. The church has been here in Asosa many years, but they have not tried to reach the Berta people. The Berta are somehow excluded from the community, they live in the rural area. The Berta speak Sudanese Arabic and Bertinia. We have two have strategies, short term and long term. Short term focus on Berta people in the town. Then when we get success in these things the long term will be using these indigenous Berta people to reach the rural Berta people. For the Berta people Christianity is for others and not for them that’s why they are 100% Muslim. His Father was totally excommunicated from the Berta community for his faith. In this society if they say Jesus Christ, they will be killed, so for that reason they will not accept Jesus. Emanuel has one young Berta man that was saved and follows him in secret. The parents don’t know because if they knew they will kill him. His name Ibrahim. He is underground, hidden. Emanuel currently pastors a church of 150. He has the special hurt for the Berta people. They don’t have access to hear about Jesus. -

Detailed Shelter Response Profile Ethiopia: Local Building Cultures For

Detailed shelter response profile Ethiopia: local building cultures for sustainable and resilient habitats Enrique Sevillano Gutierrez, Victoria Murtagh, Eugénie Crété To cite this version: Enrique Sevillano Gutierrez, Victoria Murtagh, Eugénie Crété. Detailed shelter response profile Ethiopia: local building cultures for sustainable and resilient habitats. Villefontaine, 60 p., 2018. hal-02888183 HAL Id: hal-02888183 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02888183 Submitted on 2 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. detailed shelter response profile Local Building Cultures for sustainable Ethiopia and resilient habitats 1st edition December 2018 detailed shelter response profile: ETHIOPIA | Local Building Cultures for sustainable and resilient habitats Cover images (from top to bottom): Stone houses in Axum, Tigray Region. CC - A. Davey Round chikka houses and elevated granary near Langano lake in Oromia region. CC - Ninara Dorze houses (Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region). CC - Maurits Vs Images credited with CC have a Creative Commons License 2 / 60 detailed shelter response profile: ETHIOPIA | Local Building Cultures for sustainable and resilient habitats Chikka constructions with thatched roofs near Gondar (Amhara Region) - © S. Moriset - CRAterre Konso village of Mecheke with round and rectangular houses both with thatched and CGI sheet roofs in the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region.