Does Arbitratration Process Solve Monopsonistic Behaviour in Baseball?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9 El Acento Latino Actual En El Béisbol

184 LATINOS EN EL BÉISBOL 9 EL ACENTO LATINO ACTUAL EN EL BÉISBOL Dada la importancia de los jugadores hispanos y lati- noamericanos, parece que el béisbol va a tener cada vez más un acento hispánico. Los columnistas de béisbol John S. Bowman y Joel Zoss.1 Hoy, los jugadores latinos y afronorteamericanos forman más de un tercio de los participantes de las grandes ligas. Más aún, casi siempre están a la cabeza de las ligas en varias categorías del juego. Un vistazo a cualquier nómi- na de cualquier equipo de grandes ligas o de las ligas menores muestra un sinnúmero de apellidos latinos. Sea que los aficionados se den cuenta o no, los nom- bres conocidos que aparecían en las temporadas —acor- tadas por las huelgas de 1994 y 1995— eran solo algunos de tantos latinos destacados, algunos nacidos en los Estados Unidos, que enriquecían “nuestro pasa- tiempo nacional”. Entre ellos se encontraban los que encabezaban las dos grandes ligas: ganadores del título de bateo como julio César Franco (1991, Liga Ame- 1 John S. Bowman y Joel Zoss: ob cit. Además del libro de Bowman y Zoss, este capítulo se basa en Dan Gutman: ob cit.; Leonard Koppett: The new thinking fans guide to baseball, Nueva York, Simon and Schuster, 1991; Michael Oleksak y Mary Adams Oleksak: ob cit.; Benjamin G. Rader: ob. cit.; Andrew Zimbalist: Baseball and billions, Nueva York, Basic Books, 1992. EL ACENTO LATINO ACTUAL EN EL BÉISBOL 185 ricana), Edgar Martínez (1992, 1995, Liga Ameri- cana) y Andrés Galarraga (1993, Liga Nacional); bateadores de poder y líderes en carreras impulsadas como José Canseco (ganador del título de jonronero en 1988 y 1991 de la Liga Americana, título de pro- ducidas en 1988), Juan González (dos títulos conse- cutivos de más jonrones en la Liga Americana en 1992 y 1993), y Rubén Sierra (título de carreras impulsa- das en 1989). -

MEDIA GUIDE 2019 Triple-A Affiliate of the Seattle Mariners

MEDIA GUIDE 2019 Triple-A Affiliate of the Seattle Mariners TACOMA RAINIERS BASEBALL tacomarainiers.com CHENEY STADIUM /TacomaRainiers 2502 S. Tyler Street Tacoma, WA 98405 @RainiersLand Phone: 253.752.7707 tacomarainiers Fax: 253.752.7135 2019 TACOMA RAINIERS MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Front Office/Contact Info .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Cheney Stadium .....................................................................................................................................................6-9 Coaching Staff ....................................................................................................................................................10-14 2019 Tacoma Rainiers Players ...........................................................................................................................15-76 2018 Season Review ........................................................................................................................................77-106 League Leaders and Final Standings .........................................................................................................78-79 Team Batting/Pitching/Fielding Summary ..................................................................................................80-81 Monthly Batting/Pitching Totals ..................................................................................................................82-85 Situational -

Heroes and Rallies Baseball

Heroes and Rallies Baseball Setup Pick two teams to go head to head, and fill out your lineups on the scoresheet. Each team receives 8 skill assignments to give to individual players. All of the skill assignments listed below must be used within your starting lineup for a total of 8. A player may possess two assignments if you wish. Rate your lineup by placing the appropriate notation beside a player’s name on the scoresheet. 1) star hitter (H) 2) star slugger (S) 3) star runner (R) 4) star fielder (F) 5) poor hitter (H-) 6) weak hitter (S-) 7) slow runner (R-) 8) poor fielder (F-) Once a player has a skill assignment, he cannot transfer it to another player. There is one additional skill assignment available for an ace pitcher (X). You may, however, choose not to start one. Make any pitcher a poor hitter as well (H-), so there will be two poor hitters if a pitcher is in the lineup. Game Play Roll the dice for each player who comes up to bat, reading the colored die first and the white die second. If a result occurs on the Batting chart which displays an image of a ballplayer, the inning is considered finished with no further scoring. Draw an X in the box on the scoresheet representing the current hitter’s at-bat. When his team next comes up to bat, the next player in the lineup will hit. If the color of a chart result corresponds to the color of the skill assignment of the player who is currently up to bat, the result changes to the one shown on the bottom of the Batting chart. -

Prices Realized

Mid-Summer Classic 2015 Prices Realized Lot Title Final Price 2 1932 NEWARK BEARS WORLD'S MINOR LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP GOLD BELT BUCKLE $2,022 PRESENTED TO JOHNNY MURPHY (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 3 1932 NEW YORK YANKEES SPRING TRAINING TEAM ORIGINAL TYPE I PHOTOGRAPH BY $1,343 THORNE (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 4 1936, 1937 AND 1938 NEW YORK YANKEES (WORLD CHAMPIONS) FIRST GENERATION 8" BY 10" $600 TEAM PHOTOGRAPHS (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 5 1937 NEW YORK YANKEES WORLD CHAMPIONS PRESENTATIONAL BROWN (BLACK) BAT $697 (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 6 1937 AMERICAN LEAGUE ALL-STAR TEAM SIGNED BASEBALL (JOHNNY MURPHY $5,141 COLLECTION) 7 1938 NEW YORK YANKEES WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP GOLD POCKET WATCH PRESENTED TO $33,378 JOHNNY MURPHY (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 8 INCREDIBLE 1938 NEW YORK YANKEES (WORLD CHAMPIONS) LARGE FORMAT 19" BY 11" $5,800 TEAM SIGNED PHOTOGRAPH (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 9 EXCEPTIONAL JOE DIMAGGIO VINTAGE SIGNED 1939 PHOTOGRAPH (JOHNNY MURPHY $968 COLLECTION) 10 BABE RUTH AUTOGRAPHED PHOTO INSCRIBED TO JOHNNY MURPHY (JOHNNY MURPHY $2,836 COLLECTION) 11 BABE RUTH AUTOGRAPHED PHOTO INSCRIBED TO JOHNNY MURPHY (JOHNNY MURPHY $1,934 COLLECTION) 12 1940'S JOHNNY MURPHY H&B PROFESSIONAL MODEL GAME USED BAT AND 1960'S H&B GAME $930 READY BAT (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 13 1941, 1942 AND 1943 NEW YORK YANKEES WORLD CHAMPIONS PRESENTATIONAL BLACK $880 BATS (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 14 1941-43 NEW YORK YANKEES GROUP OF (4) FIRST GENERATION PHOTOGRAPHS (JOHNNY $364 MURPHY COLLECTION) 15 LOT OF (5) 1942-43 (YANKEES VS. CARDINALS) WORLD SERIES PROGRAMS (JOHNNY MURPHY $294 COLLECTION) 16 1946 NEW YORK YANKEES TEAM SIGNED BASEBALL (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) $1,364 17 1946 NEW YORK YANKEES TEAM SIGNED BASEBALL (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) $576 18 1930'S THROUGH 1950'S JOHNNY MURPHY NEW YORK YANKEES AND BOSTON RED SOX $425 COLLECTION (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 19 1960'S - EARLY 1970'S NEW YORK METS COLLECTION INC. -

Affairs of the Heart

Volume 10 Issue 2 Article 1 2003 Affairs of the Heart Michael T. Flannery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael T. Flannery, Affairs of the Heart, 10 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 211 (2003). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol10/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Flannery: Affairs of the Heart Articles AFFAIRS OF THE HEART* MICHAEL T. FLANNERY** Baseball will be linked forever with family. Baseball is reminis- cent of fathers and sons holding hands as they enter their first ballpark together, bonding as they crack open peanuts, reach for foul balls, and cheer for their hometown heroes. While the con- cept of "Yankee" baseball particularly epitomizes these ideals, it also conjures images of sex, scandal, Hollywood stars, and tragic downfalls. In the minds of many, Yankee heroes are gods. Ultimately, however, they are just mortal men. And mortal men do not escape the randomness of life's adversities. All of our Yankee heroes have confronted the same personal issues that almost all families face, including death, divorce, custody debates, estate squabbles, domes- tic controversies, and drug addictions. For Yankee players in partic- ular, it seems the list is all too familiar. In dealing with family issues, many of our Yankee heroes have responded poorly. -

1992 Topps Baseball Card Set Checklist

1992 TOPPS BASEBALL CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Nolan Ryan 2 Rickey Henderson RB 3 Jeff Reardon RB 4 Nolan Ryan RB 5 Dave Winfield RB 6 Brien Taylor RC 7 Jim Olander 8 Bryan Hickerson 9 Jon Farrell RC 10 Wade Boggs 11 Jack McDowell 12 Luis Gonzalez 13 Mike Scioscia 14 Wes Chamberlain 15 Dennis Martinez 16 Jeff Montgomery 17 Randy Milligan 18 Greg Cadaret 19 Jamie Quirk 20 Bip Roberts 21 Buck Rodgers MG 22 Bill Wegman 23 Chuck Knoblauch 24 Randy Myers 25 Ron Gant 26 Mike Bielecki 27 Juan Gonzalez 28 Mike Schooler 29 Mickey Tettleton 30 John Kruk 31 Bryn Smith 32 Chris Nabholz 33 Carlos Baerga 34 Jeff Juden 35 Dave Righetti 36 Scott Ruffcorn Draft Pick RC 37 Luis Polonia 38 Tom Candiotti 39 Greg Olson 40 Cal Ripken/Gehrig 41 Craig Lefferts 42 Mike Macfarlane Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Jose Lind 44 Rick Aguilera 45 Gary Carter 46 Steve Farr 47 Rex Hudler 48 Scott Scudder 49 Damon Berryhill 50 Ken Griffey Jr. 51 Tom Runnells MG 52 Juan Bell 53 Tommy Gregg 54 David Wells 55 Rafael Palmeiro 56 Charlie O'Brien 57 Donn Pall 58 Brad Ausmus 59 Mo Vaughn 60 Tony Fernandez 61 Paul O'Neill 62 Gene Nelson 63 Randy Ready 64 Bob Kipper 65 Willie McGee 66 Scott Stahoviak Dft Pick RC 67 Luis Salazar 68 Marvin Freeman 69 Kenny Lofton 70 Gary Gaetti 71 Erik Hanson 72 Eddie Zosky 73 Brian Barnes 74 Scott Leius 75 Bret Saberhagen 76 Mike Gallego 77 Jack Armstrong 78 Ivan Rodriguez 79 Jesse Orosco 80 David Justice 81 Ced Landrum 82 Doug Simons 83 Tommy Greene 84 Leo Gomez 85 Jose DeLeon 86 Steve Finley 87 Bob MacDonald 88 Darrin Jackson 89 Neal -

1994 Topps Baseball Card Set Checklist

1994 TOPPS BASEBALL CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Mike Piazza 2 Bernie Williams 3 Kevin Rogers 4 Paul Carey 5 Ozzie Guillen 6 Derrick May 7 Jose Mesa 8 Todd Hundley 9 Chris Haney 10 John Olerud 11 Andujar Cedeno 12 John Smiley 13 Phil Plantier 14 Willie Banks 15 Jay Bell 16 Doug Henry 17 Lance Blankenship 18 Greg W. Harris 19 Scott Livingstone 20 Bryan Harvey 21 Wil Cordero 22 Roger Pavlik 23 Mark Lemke 24 Jeff Nelson 25 Todd Zeile 26 Billy Hatcher 27 Joe Magrane 28 Tony Longmire 29 Omar Daal 30 Kirt Manwaring 31 Melido Perez 32 Tim Hulett 33 Jeff Schwarz 34 Nolan Ryan 35 Jose Guzman 36 Felix Fermin 37 Jeff Innis 38 Brent Mayne 39 Huck Flener RC 40 Jeff Bagwell 41 Kevin Wickander 42 Ricky Gutierrez Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Pat Mahomes 44 Jeff King 45 Cal Eldred 46 Craig Paquette 47 Richie Lewis 48 Tony Phillips 49 Armando Reynoso 50 Moises Alou 51 Manuel Lee 52 Otis Nixon 53 Billy Ashley 54 Mark Whiten 55 Jeff Russell 56 Chad Curtis 57 Kevin Stocker 58 Mike Jackson 59 Matt Nokes 60 Chris Bosio 61 Damon Buford 62 Tim Belcher 63 Glenallen Hill 64 Bill Wertz 65 Eddie Murray 66 Tom Gordon 67 Alex Gonzalez 68 Eddie Taubensee 69 Jacob Brumfield 70 Andy Benes 71 Rich Becker 72 Steve Cooke 73 Bill Spiers 74 Scott Brosius 75 Alan Trammell 76 Luis Aquino 77 Jerald Clark 78 Mel Rojas 79 Billy Masse, Stanton Cameron, Tim Clark, Craig McClure 80 Jose Canseco 81 Greg McMichael 82 Brian Turang RC 83 Tom Urbani 84 Garret Anderson 85 Tony Pena 86 Ricky Jordan 87 Jim Gott 88 Pat Kelly 89 Bud Black Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 2 90 Robin Ventura 91 Rick Sutcliffe 92 Jose Bautista 93 Bob Ojeda 94 Phil Hiatt 95 Tim Pugh 96 Randy Knorr 97 Todd Jones 98 Ryan Thompson 99 Tim Mauser 100 Kirby Puckett 101 Mark Dewey 102 B.J. -

The Official Magazine of Angels Baseball

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF ANGELS BASEBALL JESSE MAGAZINE CHAVEZ VOL. 14 / ISSUE 2 / 2017 $3.00 CAMERON DANNY MAYBIN ESPINOSA MARTIN MALDONADO FRESH FACES WELCOME TO THE ANGELS TABLE OF CONTENTS BRIGHT IDEA The new LED lighting system at Angel Stadium improves visibility while reducing glare and shadows on the field. THETHE OFFICIALOFFICCIAL GAMEGA PUBLICATION OF ANGELS BASEBALL VOLUME 14 | ISSUE 2 WHAT TO LOOK FORWARD TO IN THIS ISSUE 5 STAFF DIRECTORY 43 MLB NETWORK PRESENTS 71 NUMBERS GAME 109 ARTE AND CAROLE MORENO 6 ANGELS SCHEDULE 44 FACETIME 75 THE WRIGHT STUFF 111 EXECUTIVES 9 MEET CAMERON MAYBIN 46 ANGELS ROSTER 79 EN ESPANOL 119 MANAGER 17 ELEVATION 48 SCORECARD 81 FIVE QUESTIONS 121 COACHING STAFF 21 MLB ALL-TIME 51 OPPONENT ROSTERS 82 ON THE MARK 127 WINNINGEST MANAGERS 23 CHASING 3,000 54 ANGELS TICKET INFORMATION 84 ON THE MAP 128 ANGELS MANAGERS ALL-TIME 25 THE COLLEGE YEARS 57 THE BIG A 88 ON THE SPOT 131 THE JUNIOR REPORTER 31 HEANEY’S HEADLINES 61 ANGELS 57 93 THROUGH THE YEARS 133 THE KID IN ME 34 ANGELS IN BUSINESS COMMUNITY 65 ANGELS 1,000 96 FAST FACT 136 PHOTO FAVORITES 37 ANGELS IN THE COMMUNITY 67 WORLD SERIES WIN 103 INTRODUCING... 142 ANGELS PROMOTIONS 41 COVER BOY 68 ALUMNI SPOTLIGHT 105 MAKING THE (INITIAL) CUT 144 FAN SUPPORT PUBLISHED BY PROFESSIONAL SPORTS PUBLICATIONS ANGELS BASEBALL 519 8th Ave., 25th Floor | New York, NY 10018 2000 Gene Autry Way | Anaheim, CA 92806 Tel: 212.697.1460 | Fax: 646.753.9480 Tel: 714.940.2000 facebook.com/pspsports twitter.com/psp_sports facebook.com/Angels @Angels ©2017 Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim. -

The BG News October 11, 1995

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 10-11-1995 The BG News October 11, 1995 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News October 11, 1995" (1995). BG News (Student Newspaper). 5900. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/5900 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. "Celebrating 75 years of Excellence // Inside the News Opinion City • John Miller discusses his Ward 1 candidacy Kim & Dan talk about YfOrlu • A pyramid is closed down musk. SportS • The soccer team prepares for Michigan NEWS Page 2 Wednesday, October 11,1995 Bowling Green, Ohio Volume 87, Issue 25 An inquiring mind Rush figures show growing participation Genell Pavelich events taking place the first two The BC News weekends after school had start- ed, rather than the week before. Over 350 women registered for "This new schedule of rush formal sorority rush this fall and helped to encourage people to get 280 men went through formal involved," she said. "The sched- fraternity rush, figures that are ule may have been a little too up from previous years, accord- overwhelming when everything ing to members was upon the rushees at once, of the Panhel- though, and that may have helped lenic Council in some people's decisions to and the Inter- drop out" fraternity Monahan said a few more peo- Council. -

2001 Topps Baseball Card Set Checklist

2001 TOPPS BASEBALL CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Cal Ripken Jr. 2 Chipper Jones 3 Roger Cedeno 4 Garret Anderson 5 Robin Ventura 6 Daryle Ward 8 Craig Paquette 9 Phil Nevin 10 Jermaine Dye 11 Chris Singleton 12 Mike Stanton 13 Brian R. Hunter 14 Mike Redmond 15 Jim Thome 16 Brian Jordan 17 Joe Girardi 18 Steve Woodard 19 Dustin Hermanson 20 Shawn Green 21 Todd Stottlemyre 22 Dan Wilson 23 Todd Pratt 24 Derek Lowe 25 Juan Gonzalez 26 Clay Bellinger 27 Jeff Fassero 28 Pat Meares 29 Eddie Taubensee 30 Paul O'Neill 31 Jeffrey Hammonds 32 Pokey Reese 33 Mike Mussina 34 Rico Brogna 35 Jay Buhner 36 Steve Cox 37 Quilvio Veras 38 Marquis Grissom 39 Shigetoshi Hasegawa 40 Shane Reynolds 41 Adam Piatt 42 Luis Polonia 43 Brook Fordyce Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Preston Wilson 45 Ellis Burks 46 Armando Rios 47 Chuck Finley 48 Dan Plesac 49 Shannon Stewart 50 Mark McGwire 51 Mark Loretta 52 Gerald Williams 53 Eric Young 54 Peter Bergeron 55 Dave Hansen 56 Arthur Rhodes 57 Bobby Jones 58 Matt Clement 59 Mike Benjamin 60 Pedro Martinez 61 Jose Canseco 62 Matt Anderson 63 Torii Hunter 64 Carlos Lee 65 David Cone 66 Rey Sanchez 67 Eric Chavez 68 Rick Helling 69 Manny Alexander 70 John Franco 71 Mike Bordick 72 Andres Galarraga 73 Jose Cruz Jr. 74 Mike Matheny 75 Randy Johnson 76 Richie Sexson 77 Vladimir Nunez 78 Harold Baines 79 Aaron Boone 80 Darin Erstad 81 Alex Gonzalez 82 Gil Heredia 83 Shane Andrews 84 Todd Hundley 85 Bill Mueller 86 Mark McLemore 87 Scott Spiezio 88 Kevin McGlinchy 89 Bubba Trammell 90 Manny Ramirez Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 2 91 Mike Lamb 92 Scott Karl 93 Brian Buchanan 94 Chris Turner 95 Mike Sweeney 96 John Wetteland 97 Rob Bell 98 Pat Rapp 99 John Burkett 100 Derek Jeter 101 J.D. -

Courting the Yankees

Courting the Yankees Courting the Yankees Legal Essays on the Bronx Bombers Edited by Ettie Ward Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina Copyright © 2003 Ettie Ward All Rights Reserved. ISBN: 0-89089-204-0 CIP: to apply Carolina Academic Press 700 Kent Street Durham, North Carolina 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www.cap-press.com Printed in the United States of America Contents Foreword xv I. Famous Yankees Chapter 1 Joe DiMaggio (and His Lawyer) by James R. Devine 3 I. Joe D. and Baseball— Beginning a Career of Contract Disputes 4 A. Pre-Contract Years 4 B. Joe Signs with the Pacific Coast League 5 II. Yankee Contract Disputes and Holdouts 5 A. Joe’s 1938 Salary Holdout 6 B. Joe’s 1942 Salary Holdout 7 C. Non-Legal Help with Baseball Contracts Provides Only Marginal Success 7 III. Joe Dimaggio and the Law Outside Baseball 8 A. Joe and Dorothy—Joe and Marilyn—Joe and Family Court 8 1. Joe and Dorothy 9 2. Joe and Marilyn 9 B. Joe’s Post-Baseball Business Contracts 10 IV. Joe Dimaggio as the “Toast of the Town” 11 V. Joe Dimaggio’s View of “Self” in His Twilight Years 12 VI. The Famous Dimaggio Distrust 12 A. Joe and Eddie 12 B. Joe and Barry 13 C. Joe and Dom 14 VII. Joe Dimaggio and Morris Engleberg 14 A. Attorney’s Basic Duty 14 B. Problems Arise in the Dimaggio-Engleberg Relationship 15 1. Problems with Gifts 16 2. Engleberg’s Book Deal and Confidentiality 17 3. -

Records History Opponents Player Development Miscellaneous

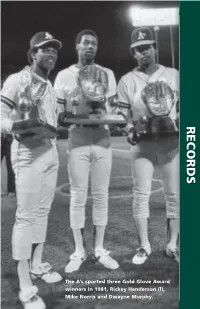

FRONT OFFICE 2008 ATHLETICS REVIEW RECORDS HISTORY OPPONENTS PLAYER DEVELOPMENT MISCELLANEOUS ▲ RECORDS 221 RECORDS The A’s sported three Gold Glove Award Gold Glove Award sported three The A’s winners in 1981, Rickey Henderson (l), Mike Norris and Dwayne Murphy. 2008 OAKLAND ATHLETICS MEDIA GUIDE 2008 OAKLAND ATHLETICS ▲ RECORDS Athletics Year-By-Year YEAR POS. W L PCT. GA/GB WILD CARD MANAGER HOME ROAD 1901 4 74 62 .544 -9 Connie Mack 42-24 32-38 FRONT OFFICE 1902 ***1 83 53 .610 +5 Connie Mack 56-17 27-36 1 1903 2 75 60 .556 -14 ⁄2 Connie Mack 44-21 31-39 1 1904 5 81 70 .536 -12 ⁄2 Connie Mack 47-31 34-39 1905 ***1 92 56 .622 +2 Connie Mack 50-23 42-33 1906 4 78 67 .538 -12 Connie Mack 48-23 30-44 1 1907 2 88 57 .607 -1 ⁄2 Connie Mack 50-20 38-37 1908 6 68 85 .444 -22 Connie Mack 46-30 22-55 1 1909 2 95 58 .621 -3 ⁄2 Connie Mack 49-27 46-31 1 1910 ****1 102 48 .680 +14 ⁄2 Connie Mack 57-19 45-29 2008 ATHLETICS 1 1911 ****1 101 50 .669 +13 ⁄2 Connie Mack 54-20 47-30 1912 3 90 62 .592 -15 Connie Mack 45-32 45-30 1 1913 ****1 96 57 .627 +6 ⁄2 Connie Mack 50-26 46-31 1 1914 ***1 99 53 .651 +8 ⁄2 Connie Mack 51-24 48-29 1 1915 8 43 109 .283 -58 ⁄2 Connie Mack 20-55 23-54 1 1916 8 36 117 .235 -54 ⁄2 Connie Mack 23-53 13-64 1 1917 8 55 98 .359 -44 ⁄2 Connie Mack 29-47 26-51 1918 8 52 76 .406 -24 Connie Mack 35-32 17-44 REVIEW 1919 8 36 104 .257 -52 Connie Mack 21-49 15-55 1920 8 48 106 .312 -50 Connie Mack 25-50 23-56 1921 8 53 100 .346 -45 Connie Mack 28-47 25-53 1922 7 65 89 .422 -29 Connie Mack 38-39 27-50 1923 6 69 83 .454 -29 Connie