Don Zimmer.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reign Men Taps Into a Compelling Oral History of Game 7 in the 2016 World Series

Reign Men taps into a compelling oral history of Game 7 in the 2016 World Series. Talking Cubs heads all top CSN Chicago producers need in riveting ‘Reign Men’ By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Thursday, March 23, 2017 Some of the most riveting TV can be a bunch of talking heads. The best example is enjoying multiple airings on CSN Chicago, the first at 9:30 p.m. Monday, March 27. When a one-hour documentary combines Theo Epstein and his Merry Men of Wrigley Field, who can talk as good a game as they play, with the video skills of world-class producers Sarah Lauch and Ryan McGuffey, you have a must-watch production. We all know “what” happened in the Game 7 Cubs victory of the 2016 World Series that turned from potentially the most catastrophic loss in franchise history into its most memorable triumph in just a few minutes in Cleveland. Now, thanks to the sublime re- porting and editing skills of Lauch and McGuffey, we now have the “how” and “why” through the oral history contained in “Reign Men: The Story Behind Game 7 of the 2016 World Series.” Anyone with sense is tired of the endless shots of the 35-and-under bar crowd whooping it up for top sports events. The word here is gratuitous. “Reign Men” largely eschews those images and other “color” shots in favor of telling the story. And what a tale to tell. Lauch and McGuffey, who have a combined 20 sports Emmy Awards in hand for their labors, could have simply done a rehash of what many term the greatest Game 7 in World Series history. -

Past CB Pitching Coaches of Year

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 62, No. 1 Friday, Jan. 4, 2019 $4.00 Mike Martin Has Seen It All As A Coach Bus driver dies of heart attack Yastrzemski in the ninth for the game winner. Florida State ultimately went 51-12 during the as team bus was traveling on a 1980 season as the Seminoles won 18 of their next 7-lane highway next to ocean in 19 games after those two losses at Miami. San Francisco, plus other tales. Martin led Florida State to 50 or more wins 12 consecutive years to start his head coaching career. By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. Entering the 2019 season, he has a 1,987-713-4 Editor/Collegiate Baseball overall record. Martin has the best winning percentage among ALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Mike Martin, the active head baseball coaches, sporting a .736 mark winningest head coach in college baseball to go along with 16 trips to the College World Series history, will cap a remarkable 40-year and 39 consecutive regional appearances. T Of the 3,981 baseball games played in FSU coaching career in 2019 at Florida St. University. He only needs 13 more victories to be the first history, Martin has been involved in 3,088 of those college coach in any sport to collect 2,000 wins. in some capacity as a player or coach. What many people don’t realize is that he started He has been on the field or in the dugout for 2,271 his head coaching career with two straight losses at of the Seminoles’ 2,887 all-time victories. -

Analysis of Annual Cbunci1

Analysis ofAnnual Cbunci1 The (burch and the \Xar in Lebanon A QuarterlyJournal of theAssociation ofAdventist fununs VolumeS, Number2 Reviews of Ronald Numbers' Book ' By Schwarz, G ,the White F5ttte Ana Others, Plus hers'Response SPECTRUM EDITORIAL BOARD Ottilie Stafford Richard Emmerson Margaret McFarland Alvin L. Kwiram, Chairman South Lancaster, Massachusetts College Place, Washington Ann Arbor, Michigan Seattle, Washington EDITORS Helen Evans La Vonne Neff Roy Branson Keene, Texas College Place, Washington Roy Branson Washington, D.C. Charles Scriven Judy Folkenberg Ronald Numbers Molleurus Couperus Washington, D.C. Madison, Wisconsin Lorna Linda, California CONSULTING Lawrence Geraty Edward E. Robinson Tom Dybdahl Berrien Springs, Michigan Chicago, Illinois Takoma Park, Maryland EDITORS Fritz Guy Gerhard Svrcek-Seiler Gary Land Kjeld' Andersen Berrien Springs, Michigan Lystrup, Denmark Riverside, California Vienna, Austria Roberta J. Moore Eric Anderson J orgen Henriksen Betty Stirling Riverside, California Angwin, California North Reading, Massachusetts Washington, D.C. Charles Scriven Raymond Cottrell Eric A. Magnusson L. E. Trader St. Helena, California Washington, D.C. Cooranbong, Australia Darmstadt, Germany Association of Adventist Forums EXECUTIVE Of Finance Regional Co-ordinator Rudy Bata COMMITTEE Ronald D. Cople David Claridge Rocky Mount, North Carolina Silver Spring, Maryland Rockville, Maryland President Grant N. Mitchell Glenn E. Coe Of International Affairs Systems Consultant Fresno, California West Hartford, Connecticut William Carey Molleurus Couperus Lanny H. Fisk Lorna Linda, California Silver Spring, Maryland Vice President Walla Walla, Washington Leslie H. Pitton, Jr. Of Outreach Systems Manager Reading, Pennsylvania Karen Shea Joseph Mesar Don McNeill Berrien Springs, Michigan Executive Secretary Boston, Massachusetts Spencerville, Maryland Viveca Black Stan Aufdemberg Treasurer Arlington, Virginia STAFF Lorna Linda, California Administrative Secretary Richard C. -

"Electric October" by Kevin Cook

John Kosner Home World U.S. Politics Economy Business Tech Markets Opinion Life & Arts Real Estate WSJ. Magazine Search BOOKS | BOOKSHELF SHARE FACEBOOKThe Salt of the Diamond TWITTERA look back at the 1947 World Series—in which Joe DiMaggio and Jackie Robinson played—focusing on six of its unsung heroes. Edward Kosner reviews ‘Electric October’ by Kevin Cook. EMAIL PERMALINK PHOTO: BETTMANN ARCHIVE By Edward Kosner Sept. 28, 2017 6:33 pm ET SAVE PRINT TEXT 7 Of all sports, baseball lives the most in its past. Those meticulous statistics help, of course. And the fact that, over the years, the game has attracted more gifted writers than any other, from Ring Lardner to John Updike, Robert Coover and Philip Roth. Random baseball moments—not just epic coups like Bobby Thomson’s 1951 “miracle” home run—persist in memory long after they should have evanesced. Kevin Cook’s heartfelt and entertaining “Electric October” is ostensibly about the 1947 World Series between Joe DiMaggio’s Yankees and the Dodgers of Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese and Dixie Walker. The book is really about the lost drama and culture of mid- 20th-century baseball still embedded in the minds of old-timers. A onetime editor at Sports Illustrated, Mr. Cook doesn’t focus on the stars DiMaggio and Robinson. Instead he tells the stories of two baseball lifers—the Yankee manager Bucky Harris and the Dodger skipper Burt Shotton—and four bit players: Yankee journeyman pitcher Bill Bevens and Dodgers pinch hitter Cookie Lavagetto, who broke up Bevens’s no- RECOMMENDED VIDEOS hitter in game four; Al Gionfriddo, a diminutive scrub who kept Brooklyn in the series with NYC Sets Up Traveler- a sensational catch in game six; and George (Snuffy) Stirnweiss, a Yankee infielder who was 1. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

H Elp in G C Oac H Es G a in a N E D Ge Sin C E 1 98 7

January 10th January Pittsburgh DoubleTree by Hilton SOFTBALL SPEAKERS AND TOPICS Visit www.pacoachesclinic.com for a detailed event SOFTBALL SPEAKERS AND TOPICS FRI JAN 11 Registration Opens: 9:30am, Sessions: 11:20am-9:20pm FRI JAN 11 Registration Opens: 9:30am, Sessions: 11:20am-9:20pm SAT JAN 12 Registration Opens: 8:00am, Sessions: 8:30am-1:50pm schedule including presentation times and rooms. SAT JAN 12 Registration Opens: 8:00am, Sessions: 8:30am-1:50pm - STEPHANIE VANBRAKLE PROTHRO Green TreeGreen FEATURED SOFTBALL SPEAKER FEATURED SOFTBALL SPEAKER UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA CAROL BRUGGEMAN Prothro is preparing for her eighth season as pitching coach at her alma mater JOHN TSHIDA after helping guide the Crimson Tide to yet another stellar campaign. Alabama - NIVERSITY OF T HOMAS INNESOTA 12th, 12th, 2019 NFCA EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR finished the 2018 season ranked in the top 25 for the 19th-straight year. The U S . T , M team made its 20th consecutive NCAA Tournament appearance and advanced In the softball world, if you name it, chances are Bruggeman has done it. Regardless of division, if you're talking about the best coaches in college A longtime Division I coach at Michigan, Purdue and Louisville, to the NCAA Super Regional round for an NCAA-record 14th straight year. During her softball, you have to include Tshida. A member of the National Fastpitch Bruggeman also traveled to Australia to serve as head coach of a college tenure, Alabama made four appearances in the World Series and captured the first national Coaches Association Hall of Fame, Tshida has won three national team that won a gold medal with USA-Athletes International in 2011. -

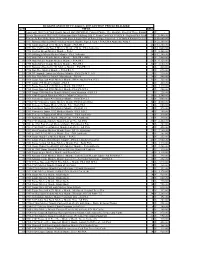

November 13, 2010 Prices Realized

SCP Auctions Prices Realized - November 13, 2010 Internet Auction www.scpauctions.com | +1 800 350.2273 Lot # Lot Title 1 C.1910 REACH TIN LITHO BASEBALL ADVERTISING DISPLAY SIGN $7,788 2 C.1910-20 ORIGINAL ARTWORK FOR FATIMA CIGARETTES ROUND ADVERTISING SIGN $317 3 1912 WORLD CHAMPION BOSTON RED SOX PHOTOGRAPHIC DISPLAY PIECE $1,050 4 1914 "TUXEDO TOBACCO" ADVERTISING POSTER FEATURING IMAGES OF MATHEWSON, LAJOIE, TINKER AND MCGRAW $288 5 1928 "CHAMPIONS OF AL SMITH" CAMPAIGN POSTER FEATURING BABE RUTH $2,339 6 SET OF (5) LUCKY STRIKE TROLLEY CARD ADVERTISING SIGNS INCLUDING LAZZERI, GROVE, HEILMANN AND THE WANER BROTHERS $5,800 7 EXTREMELY RARE 1928 HARRY HEILMANN LUCKY STRIKE CIGARETTES LARGE ADVERTISING BANNER $18,368 8 1930'S DIZZY DEAN ADVERTISING POSTER FOR "SATURDAY'S DAILY NEWS" $240 9 1930'S DUCKY MEDWICK "GRANGER PIPE TOBACCO" ADVERTISING SIGN $178 10 1930S D&M "OLD RELIABLE" BASEBALL GLOVE ADVERTISEMENTS (3) INCLUDING COLLINS, CRITZ AND FONSECA $1,090 11 1930'S REACH BASEBALL EQUIPMENT DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $425 12 BILL TERRY COUNTERTOP AD DISPLAY FOR TWENTY GRAND CIGARETTES SIGNED "TO BARRY" - EX-HALPER $290 13 1933 GOUDEY SPORT KINGS GUM AND BIG LEAGUE GUM PROMOTIONAL STORE DISPLAY $1,199 14 1933 GOUDEY WINDOW ADVERTISING SIGN WITH BABE RUTH $3,510 15 COMPREHENSIVE 1933 TATTOO ORBIT DISPLAY INCLUDING ORIGINAL ADVERTISING, PIN, WRAPPER AND MORE $1,320 16 C.1934 DIZZY AND DAFFY DEAN BEECH-NUT ADVERTISING POSTER $2,836 17 DIZZY DEAN 1930'S "GRAPE NUTS" DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $1,024 18 PAIR OF 1934 BABE RUTH QUAKER -

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

Baseball's Worst Team Fred Worth Department of Mathematics and Computer Science

Academic Forum 21 2003-04 Baseball's Worst Team Fred Worth Department of Mathematics and Computer Science Abstract - In this paper we will look at some of the worst teams in baseball history and try to decide which team was indeed the worst. We will look at some statistics that will compare the teams to the teams of their day to try to account for the differences in eras. Introduction Much discussion is heard regarding who the best player, hitter, pitcher, etc. in baseball history may have been. There is not typically a lot of discussion on who the worst in any of these categories may be. The 2003 season changed that a little bit due to the incredible futility displayed by the Detroit Tigers. In this paper, we will look at some of the worst teams in baseball history and see if, indeed, the Tigers qualify. Preliminary Criteria The first consideration needs to be what criteria we will use to make our determination of the worst team. Certainly the teams win-loss record and winning percentage should be considered. Since the word "worst" implies a comparison, we should also look a how far the teams finished out of first place and, to see how truly bad they were, how far they finished behind the next-to- last-place team. Candidates The following table lists the teams we will consider for the designation as the worst team in baseball history. There have been other teams that were very bad. Obviously the choice of candidates is fairly arbitrary, however, most would agree that these nine teams were rather bad. -

Ba Mss 121 Bl-587.69 – Bl-593.69

Collection Number BA MSS 121 BL-587.69 – BL-593.69 Title Tom Meany Scorebooks Inclusive Dates 1947 – 1963 NY teams Access By appointment during regular hours, email [email protected]. Abstract These scorebooks have scored games from spring training, All-Star games, and World Series games, and a few regular season games. Volume 1 has Jackie Robinson’s first game, April 15, 1947. Biography Tom Meany was recruited to write for the new Brooklyn edition of the New York Journal in 1922. The following year he earned a byline in the Brooklyn Daily Times as he covered the Dodgers. Over the years, Meany's sports writing career saw stops at numerous papers including the New York Telegram (later the World-Telegram), New York Star, Morning Telegraph, as well as magazines such as PM and Collier's. Following his sports writing career, Meany joined the Yankees in 1958. In 1961 he joined the expansion Mets as publicity director and later served as promotions director before his untimely death in 1964 at the age of 60. He received the Spink Award in 1975. Source: www.baseballhall.org Content List Volume 1 BL-587.69 1947 - Spring training, season games April 15, Jackie Robinson’s first game World Series - Dodgers v. Yankees 1948 - Spring training Volume 2 BL-588.69 1948 – Season games World Series, Indians vs. Braves 1962 - World Series, Giants vs. Yankees Volume 3 BL-589.69 1949 -Spring training, season games 1950 - May, Jul 11 All-Star game World Series, Yankees vs. Phillies 1951 - Playoff games, Dodgers vs. Giants World Series, Giants vs. -

F(Error) = Amusement

Academic Forum 33 (2015–16) March, Eleanor. “An Approach to Poetry: “Hombre pequeñito” by Alfonsina Storni”. Connections 3 (2009): 51-55. Moon, Chung-Hee. Trans. by Seong-Kon Kim and Alec Gordon. Woman on the Terrace. Buffalo, New York: White Pine Press, 2007. Peraza-Rugeley, Margarita. “The Art of Seen and Being Seen: the poems of Moon Chung- Hee”. Academic Forum 32 (2014-15): 36-43. Serrano Barquín, Carolina, et al. “Eros, Thánatos y Psique: una complicidad triática”. Ciencia ergo sum 17-3 (2010-2011): 327-332. Teitler, Nathalie. “Rethinking the Female Body: Alfonsina Storni and the Modernista Tradition”. Bulletin of Spanish Studies: Hispanic Studies and Researches on Spain, Portugal and Latin America 79, (2002): 172—192. Biographical Sketch Dr. Margarita Peraza-Rugeley is an Assistant Professor of Spanish in the Department of English, Foreign Languages and Philosophy at Henderson State University. Her scholarly interests center on colonial Latin-American literature from New Spain, specifically the 17th century. Using the case of the Spanish colonies, she explores the birth of national identities in hybrid cultures. Another scholarly interest is the genre of Latin American colonialist narratives by modern-day female authors who situate their plots in the colonial period. In 2013, she published Llámenme «el mexicano»: Los almanaques y otras obras de Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (Peter Lang,). She also has published short stories. During the summer of 2013, she spent time in Seoul’s National University and, in summer 2014, in Kyungpook National University, both in South Korea. https://www.facebook.com/StringPoet/ The Best Players in New York Mets History Fred Worth, Ph.D.