1 'The Invisible Boundaries of the Karanga: Considering Pre-Colonial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promotion of Climate-Resilient Lifestyles Among Rural Families in Gutu

Promotion of climate-resilient lifestyles among rural families in Gutu (Masvingo Province), Mutasa (Manicaland Province) and Shamva (Mashonaland Central Province) Districts | Zimbabwe Sahara and Sahel Observatory 26 November 2019 Promotion of climate-resilient lifestyles among rural families in Gutu Project/Programme title: (Masvingo Province), Mutasa (Manicaland Province) and Shamva (Mashonaland Central Province) Districts Country(ies): Zimbabwe National Designated Climate Change Management Department, Ministry of Authority(ies) (NDA): Environment, Water and Climate Development Aid from People to People in Zimbabwe (DAPP Executing Entities: Zimbabwe) Accredited Entity(ies) (AE): Sahara and Sahel Observatory Date of first submission/ 7/19/2019 V.1 version number: Date of current submission/ 11/26/2019 V.2 version number A. Project / Programme Information (max. 1 page) ☒ Project ☒ Public sector A.2. Public or A.1. Project or programme A.3 RFP Not applicable private sector ☐ Programme ☐ Private sector Mitigation: Reduced emissions from: ☐ Energy access and power generation: 0% ☐ Low emission transport: 0% ☐ Buildings, cities and industries and appliances: 0% A.4. Indicate the result ☒ Forestry and land use: 25% areas for the project/programme Adaptation: Increased resilience of: ☒ Most vulnerable people and communities: 25% ☒ Health and well-being, and food and water security: 25% ☐ Infrastructure and built environment: 0% ☒ Ecosystem and ecosystem services: 25% A.5.1. Estimated mitigation impact 399,223 tCO2eq (tCO2eq over project lifespan) A.5.2. Estimated adaptation impact 12,000 direct beneficiaries (number of direct beneficiaries) A.5. Impact potential A.5.3. Estimated adaptation impact 40,000 indirect beneficiaries (number of indirect beneficiaries) A.5.4. Estimated adaptation impact 0.28% of the country’s total population (% of total population) A.6. -

For Human Dignity

ZIMBABWE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION For Human Dignity REPORT ON: APRIL 2020 i DISTRIBUTED BY VERITAS e-mail: [email protected]; website: www.veritaszim.net Veritas makes every effort to ensure the provision of reliable information, but cannot take legal responsibility for information supplied. NATIONAL INQUIRY REPORT NATIONAL INQUIRY REPORT ZIMBABWE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION ZIMBABWE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION For Human Dignity For Human Dignity TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................. vii ACRONYMS.................................................................................................................................................... ix GLOSSARY OF TERMS .................................................................................................................................. xi PART A: INTRODUCTION TO THE NATIONAL INQUIRY PROCESS ................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Establishment of the National Inquiry and its Terms of Reference ....................................................... 2 1.2 Methodology ..................................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 2: THE NATIONAL INQUIRY PROCESS ......................................................................................... -

Small Grain Production As an Adaptive Strategy to Climate Change in Mangwe District, Matabeleland South in Zimbabwe

Jàmbá - Journal of Disaster Risk Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-845X, (Print) 1996-1421 Page 1 of 9 Original Research Small grain production as an adaptive strategy to climate change in Mangwe District, Matabeleland South in Zimbabwe Authors: This article assesses the feasibility of small grains as an adaptive strategy to climate change in 1 Tapiwa Muzerengi the Mangwe District in Zimbabwe. The change in climate has drastically affected rainfall Happy M. Tirivangasi2 patterns across the globe and in Zimbabwe in particular. Continuous prevalence of droughts Affiliations: in Zimbabwe, coupled with other economic calamities facing the Southern African country, 1Department of Community has contributed to a larger extent to the reduction in grain production among communal Development, University of farmers, most of whom are in semi-arid areas. This has caused a sudden increase in food KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa shortages, particularly in the Mangwe District, as a result of erratic rainfall, which has negatively affected subsistence farming. This article was deeply rooted in qualitative research 2Department of Sociology methodologies. Purposive sampling was used to sample the population. The researchers used and Anthropology, University key informant interviews, focus group discussions and secondary data to collect data. Data of Limpopo, Sovenga, South were analysed using INVIVO software, a data analysis tool that brings out themes. The results Africa of the study are presented in the form of themes. The study established that small grains Corresponding author: contributed significantly to addressing food shortages in the Mangwe District. The study Happy Tirivangasi, results revealed that small grains were a reliable adaptive strategy to climate change as they [email protected] increased food availability, accessibility, utilisation and stability. -

Dr. Paradzai Pathias Bongo1 Community-Based Disaster Risk

Dr. Paradzai Pathias Bongo1 Community-based disaster risk reduction in the context of climate change: The case of rural Zimbabwe INTRODUCTION This paper is based on a current Department for Overseas Development (DFID) funded Community-Based Disaster Risk Management project in the semi-arid Southern part of Zimbabwe, entitled ‘Mainstreaming Livelihood Centred Approaches to Disaster Management’.2 The paper posits the need for building, supporting and strengthening communities’ livelihoods so that they become more resilient during and after a hazard as they mainly use their local resources, institutional arrangements and own conceptions of risk. It is envisaged that community based risk reduction plans could inform meso and macro policy levels, thereby shaping the current disaster management regime prevailing in the country. Since time immemorial, human beings have been faced with various types of hazards, most of which turned into disasters. In such cases, mainstream and official prescriptions have focused on response and relief aid, without paying due regard to the need for reducing the vulnerability of affected communities by increasing their resilience through building their capacity. With the effects of climate change worsening globally, communities will be called to be even more responsive to these changes, as they affect them in newer and unique ways. They will therefore have to be supported in their adaptation measures, considering that most developing world governments are already cash-strapped to fund development and investment, let alone disaster management projects. Yet at the same time, risks that communities face dictate that livelihood-centred approaches be mainstreamed into 1 Projects Manager Livelihoods and Disaster Risk Management, Reducing Vulnerability (RV) Programme, Practical Action Southern Africa, Zimbabwe. -

Leopard Population Density and Community Attitudes Towards Leopards in and Around Debshan Ranch, Shangani, Zimbabwe

LEOPARD POPULATION DENSITY AND COMMUNITY ATTITUDES TOWARDS LEOPARDS IN AND AROUND DEBSHAN RANCH, SHANGANI, ZIMBABWE A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE of RHODES UNIVERSITY Department of Zoology and Entomology By PHUMUZILE NYONI DECEMBER 2015 SUPERVISOR: DR D. M. PARKER ABSTRACT ABSTRACT Leopards (Panthera pardus) are regarded as one of the most resilient large carnivore species in the world and can persist in human dominated landscapes, areas with low prey availability nd highly fragmented habitats. However, recent evidence across much of their range reveals declining populations. In Zimbabwe, 500 Convention for the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) export tags are available annually for leopards as hunting trophies, despite limited accurate data on the leopard populations of the country. Moreover, when coupled with the massive land conversions under the controversial National Land Reform Programme (NLRP), leopard populations in Zimbabwe are in dire need of assessment. My study was conducted on Debshan ranch, Shangani, Zimbabwe, which is a commercial cattle (Bos indicus) ranch but also supports a high diversity of indigenous wildlife including an apparently healthy leopard population. However, the NLRP has resulted in an increase in small-holder subsistence farming communities around the ranch (the land was previously privately owned and divided into larger sub-units). This change in land-use means that both human and livestock densities have increased and the potential for human leopard conflict has increased. I estimated the leopard population density of the ranch and assessed community attitudes towards leopards in the communities surrounding the ranch. To estimate population densities, I performed spoor counts and conducted a camera trapping survey. -

Zimbabwe Emergency Water and Sanitation Project (Zewsp)

ZIMBABWE EMERGENCY WATER AND SANITATION PROJECT (ZEWSP) Final Results Report (August 2005-August 2006) SUBMITTED TO THE OFFICE OF FOREIGN DISASTER ASSISTANCE (OFDA) UNITED STATTES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT (USAID) Cooperative Agreement No: DFD-G-00-05-00172-00 In Country Contact Address: Leslie Scott National Director 59 Joseph Road Off Nursery Road, Mount Pleasant, Harare, Zimbabwe Tel: (263 – 4) 301 715/709, 369027/8, Fax: (263- 4) 301 330 Email: [email protected] December 2006 1 A. SUMMARY Organization: World Vision, Inc Headquarters Mailing Address: 300 I Street, NE, Washington, DC 20002 Date: December 2006 Headquarter Contact Person: Dennis Cherian, Program/Technical Specialist, Grants Acquisition and Management Telephone: +1(202) 572 6378 Fax: +1(202) 572 6480 Email Address: [email protected] Field Contact Person: Leslie Scott Telephone: + (263) 4 301 715/709, 369027/8 Fax: + (263) 4 301 330 Email: [email protected] Program Title: Zimbabwe Emergency Water and Sanitation Project (ZEWSP) USAID/OFDA Grant No: DFD-G-00-05-00172-00 Country/Region: Zimbabwe, Southern Africa Type of Disaster/Hazard: Complex emergency resulting from drought Time Period covered by this report: August 2, 2005 - August 31, 2006 2 B. PROGRAM OVERVIEW AND PERFORMANCE 1.0. OVERALL PROJECT OBJECTIVE To increase access to potable water, sanitation and hygiene for 65, 000 individuals (13,000 households) in the highly drought- and HIV/AIDS – affected districts of Beitbridge, Gwanda and Mangwe in Matabeleland, South Province through the provision of 300 water points. 1.1. OBJECTIVE Improved access to potable water, sanitation and hygiene for 65,000 individuals (13,000 vulnerable households) 1.2. -

Hyenas of the Limpopo

Hyenas of the Limpopo Hyenas of the Limpopo The Social Politics of Undocumented Movement across South Africa’s Border with Zimbabwe Xolani Tshabalala Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 729 Faculty of Arts and Sciences Linköping 2017 Linköping Studies in Arts and Science • No. 729 At the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Linköping University, research and doctoral studies are carried out within broad problem areas. Research is organized in interdisciplinary research environments and doctoral studies mainly in graduate schools. Jointly, they publish the series Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. This thesis comes from Institute for Research on Migration, Ethnicity and Society (REMESO) at the Department of Social and Welfare Studies. Distributed by: Department of Social and Welfare Studies Linköping University 581 83 Linköping Xolani Tshabalala Hyenas of the Limpopo: The Social Politics of Undocumented Movement across South Africa’s Border with Zimbabwe Edition 1:1 ISBN 978-91-7685-408-2 ISSN 0282-9800 © Xolani Tshabalala Department of Social and Welfare Studies 2017 Typesetting and cover by Merima Mešić Printed by: LiU-Tryck, Linköping 2017 Acknowledgements The decision to pursue PhD level studies at what in the beginning seemed like a faraway place represented a leap into the unknown. Along the winding journey that has brought me to this point, I have accumulated many debts. I will never be able to recall or pay them all, and in explicitly acknowledging the help of some people here, I remain equally indebted, in the spirit of the gift, to many others whose generosity is all the more appreciated in its namelessness. -

Zimbabwe Evaluation November 2017

Independent Program Evaluation Report For Caritas Danmark Rural Development Program in Zimbabwe By Centre for Development, Research and Evaluation International Africa Pindai Sithole, PhD (Team Leader) (Qualitative Evaluation Methods &Community Development Expert) Ganyani Khosa (Quantitative Evaluation Methods & ICT for Development Expert) November 2017 Page | Table of Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures .................................................................................................................................................. ii Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... iv Team Composition ........................................................................................................................................ iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................................1 SECTION ONE ..................................................................................................................................................3 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................3 1.1 Brief development program description and its rationale .........................................3 -

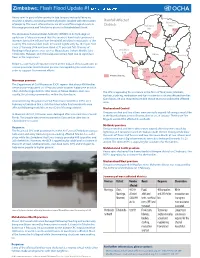

ZIM-Infographic-Flood-06 A4 07Feb2014 Zimbabwe Flash Flood - February 2014.Ai

¡ ¢ £ ¤ ¥ ¦ § ¨ © ¡ ¥ Heavy rains in parts of the country in late January and early February resulted in deaths and displacement of people, coupled with destruction Rainfall A!ected Mashonaland of property. The worst a!ected areas are Chivi and Masvingo districts in Districts Mashonaland Central Masvingo province and Tsholotsho district in Matabeleland North. West Shamva The Zimbabwe National Water Authority (ZINWA) in its hydrological Makonde Binga update on 5 February warned that the country’s dam levels continue to Harare increase due to the in"ows from the rainfall activities in most parts of the Gokwe South country. The national dam levels increased signicantly by 10.29 per cent since 27 January 2014 and now stand at 71 per cent full. Chances of Mashonaland "ooding in "ood prone areas such as Muzarabani, Gokwe, Middle Sabi, Matabeleland East Tsholotsho, Malapati and Chikwalakwala remain high due to signicant North Midlands Manicaland "ows in the major rivers. Tsholotsho Gutu Bulawayo Below is a summary of reports received on the impact of incessant rains in Masvingo Chivi various provinces. Humanitarian partners are appealing for assistance in Matabeleland Masvingo order to support Government e!orts. Mangwe South A!ected districts Gwanda Mwenezi Chiredzi Masvingo province The Department of Civil Protection (DCP) reports that about 400 families needed to be evacuated on 3 February while another 4,000 were at risk in Chivi and Masvingo districts after levels at Tokwe-Mukorsi dam rose The CPC is appealing for assistance in the form of food, tents, blankets, rapidly, threatening communities within the dam basin. buckets, clothing, medication and fuel in order to assist the a!ected families. -

Practical Experiences of Community Based Disaster Risk Management Planning in Matabeleland South, Zimbabwe

Practical experiences of Community Based Disaster Risk Management Planning in Matabeleland South, Zimbabwe Community VCA meeting Marula Ward 1 Practical experiences of CBDRM planning in Matabeleland South, Zimbabwe Preamble Growth, development and progress towards the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) is increasingly being undermined by the impact of a variety of hazards, both natural and man- made. The rising cost of disasters in both developed and emerging countries has moved disaster risk reduction to centre stage in the battle against poverty. One hundred and sixty eight countries (168) have signed up to the ISDR sponsored Hyogo Framework for Action which commits signatories to a strategy for building the resilience of nations and communities to disasters. The strategy builds on three strategic goals which ultimate aim to mainstream disaster risk reduction into all development processes. The evidence is clear, disasters are not natural phenomena, but rather problems of poor development planning, exacerbated by rising populations, increasing poverty, environmental degradation and the impacts of climate change. While increasing frequency and intensity of meteorological events is partly to blame, the vulnerability and lack of preparedness of many sectors of society determine the outcome of hazardous events. It has been clearly demonstrated that awareness, preparedness and resilience determine the outcome of the impact of any hazard, be it drought or flood, earthquake or cyclone. Changes in patterns of human behaviour and decision-making at all levels of government and society can lead to substantial reductions in disaster risk. Public awareness of natural hazards and disaster risk reduction education are pre-requisites for effective catastrophic risk management at country and regional levels. -

Land Use-Land Cover Changes and Mopani Worm Harvest in Mangwe

Ndlovu et al. Environ Syst Res (2019) 8:11 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40068-019-0141-5 RESEARCH Open Access Land use land cover changes and Mopani worm harvest− in Mangwe District in Plumtree, Zimbabwe Iphithule Ndlovu, Wilfred Njabulo Nunu* , Nicholas Mudonhi, Oliver Dube and Auther Maviza Abstract Background: Mopani worms have been considered a critical food security resource as people living in Mopani woodlands depend on the worms both as a food source and as an income generating resource. These become a readily available substitute if agriculture fails and droughts loom. However the yields from these worms have been dwindling over the years and this has been associated with land use land cover changes as the worms depend on vegetation. This research sought to investigate the relationship between− land use land cover changes and Mopani worm harvests in Mangwe District in Plumtree from the period 2007 to 2016 in Zimbabwe.− Methods: Satellite imagery was collected using LandSat 5 and LandSat 8 satellite and then classifed using the Semi- Automatic Classifcation plugin in Quantum Geographic Information System to identify trees, dams, bare soil and settlements. Thematic maps were then produced and used to quantify extent of Land Use–Land Cover changes in the period from 2007 to 2016. Ground control data was collected using hand held Global Positioning System. Harvests trends (and reasons thereof) were estimated through usage of interviewer administered questionnaires on selected Mopani worm harvesters and harvest data kept by the community leaders. Results: Results showed that settlements and bare soil cover had greatly increased from 2007 to 2016. -

A4 Template 4 Page Bklet Text on All Pages

Acknowledgements COPING WITH DROUGHT Research findings from Bulilima and Mangwe This study was carried out by Sithembisiwe Ndlovu with the support of Dr Paradzayi Bongo and Reckson Matengarufu and the cooperation of the communities of Mangwe and Bulilima. Districts, Matabeleland South, Editing and formatting by Ed Phillips. Zimbabwe Sithembisiwe Ndlovu References Local perceptions of drought include shortages of food and inadequate grazing, as well as low and erratic rainfall; yet the diverse drought coping and risk reduction strategies being promoted Dekker, M. 2004. Risk, Resettlement and Rela- Scoones, I., Chibudu, C., Chikura, S., Jeran in the two districts are mainly based on agriculture and natural resources. While livelihood tions; Social Security in Rural Zimbabwe. Tim- yama, P., Machaka, D., Machanja, W., Mavedz- diversification has increased household income and resilience, badly managed strategies can bergern Institute, Netherlands. enge, B., Mombeshora, B., Mudhara, M., exacerbate drought risks. Socio-economic factors including HIV/AIDS, land degradation and Mudziwo, C., Murimbarima, F. and Zirereza, B. migration have limited opportunities while food aid has increased dependency. The role of Food and Agriculture Organisation, 2003. Se- 1996. Hazards and Opportunities: Farming institutions is critical for supporting knowledge transfer and the development of sustainable lected Current Issues in the Forest Sector. Food Lvelihoods in Dryland Africa- Lessons From community owned initiatives. and Agricultural Organization (FAO), Rome. Zimbabwe. Zed Books Limited, London. 1.0. Introduction 2.0. The Study site Zimbabwe Meteorological Services, 2009. Gandure, S. 2005. Coping with and Adapting to Drought in Zimbabwe. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Witwatersrand, Johannes- The increasing prevalence of drought in Bulilima and Mangwe Districts of Matabeleland burg.