The Dalits of Nepal and a New Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code Under Name Girls Boys Total Girls Boys Total 010290001

P|D|LL|S G8 G10 Code Under Name Girls Boys Total Girls Boys Total 010290001 Maiwakhola Gaunpalika Patidanda Ma Vi 15 22 37 25 17 42 010360002 Meringden Gaunpalika Singha Devi Adharbhut Vidyalaya 8 2 10 0 0 0 010370001 Mikwakhola Gaunpalika Sanwa Ma V 27 26 53 50 19 69 010160009 Phaktanglung Rural Municipality Saraswati Chyaribook Ma V 28 10 38 33 22 55 010060001 Phungling Nagarpalika Siddhakali Ma V 11 14 25 23 8 31 010320004 Phungling Nagarpalika Bhanu Jana Ma V 88 77 165 120 130 250 010320012 Phungling Nagarpalika Birendra Ma V 19 18 37 18 30 48 010020003 Sidingba Gaunpalika Angepa Adharbhut Vidyalaya 5 6 11 0 0 0 030410009 Deumai Nagarpalika Janta Adharbhut Vidyalaya 19 13 32 0 0 0 030100003 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Janaki Ma V 13 5 18 23 9 32 030230002 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Singhadevi Adharbhut Vidyalaya 7 7 14 0 0 0 030230004 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Jalpa Ma V 17 25 42 25 23 48 030330008 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Khambang Ma V 5 4 9 1 2 3 030030001 Ilam Municipality Amar Secondary School 26 14 40 62 48 110 030030005 Ilam Municipality Barbote Basic School 9 9 18 0 0 0 030030011 Ilam Municipality Shree Saptamai Gurukul Sanskrit Vidyashram Secondary School 0 17 17 1 12 13 030130001 Ilam Municipality Purna Smarak Secondary School 16 15 31 22 20 42 030150001 Ilam Municipality Adarsha Secondary School 50 60 110 57 41 98 030460003 Ilam Municipality Bal Kanya Ma V 30 20 50 23 17 40 030460006 Ilam Municipality Maheshwor Adharbhut Vidyalaya 12 15 27 0 0 0 030070014 Mai Nagarpalika Kankai Ma V 50 44 94 99 67 166 030190004 Maijogmai Gaunpalika -

Women's Empowerment at the Frontline of Adaptation

Women’s Empowerment at the Frontline of Adaptation Emerging issues, adaptive practices, and priorities in Nepal ICIMOD Working Paper 2014/3 1 About ICIMOD The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, ICIMOD, is a regional knowledge development and learning centre serving the eight regional member countries of the Hindu Kush Himalayas – Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan – and based in Kathmandu, Nepal. Globalization and climate change have an increasing influence on the stability of fragile mountain ecosystems and the livelihoods of mountain people. ICIMOD aims to assist mountain people to understand these changes, adapt to them, and make the most of new opportunities, while addressing upstream-downstream issues. We support regional transboundary programmes through partnership with regional partner institutions, facilitate the exchange of experience, and serve as a regional knowledge hub. We strengthen networking among regional and global centres of excellence. Overall, we are working to develop an economically and environmentally sound mountain ecosystem to improve the living standards of mountain populations and to sustain vital ecosystem services for the billions of people living downstream – now, and for the future. ICIMOD gratefully acknowledges the support of its core donors: The Governments of Afghanistan, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Norway, Pakistan, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. 2 ICIMOD Working Paper 2014/3 Women’s Empowerment at the Frontline of Adaptation: Emerging issues, adaptive practices, and priorities in Nepal Dibya Devi Gurung, WOCAN Suman Bisht, ICIMOD International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Kathmandu, Nepal, August 2014 Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development GPO Box 3226, Kathmandu, Nepal Copyright © 2014 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) All rights reserved. -

Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal

IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal Country Name Nepal Official Name Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal Regional Bureau Bangkok, Thailand Assessment Assessment Date: From 16 October 2009 To: 6 November 2009 Name of the assessors Rich Moseanko – World Vision International John Jung – World Vision International Rajendra Kumar Lal – World Food Programme, Nepal Country Office Title/position Email contact At HQ: [email protected] 1/105 IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Country Profile....................................................................................................................................................................3 1.1. Introduction / Background.........................................................................................................................................5 1.2. Humanitarian Background ........................................................................................................................................6 1.3. National Regulatory Departments/Bureau and Quality Control/Relevant Laboratories ......................................16 1.4. Customs Information...............................................................................................................................................18 2. Logistics Infrastructure .....................................................................................................................................................33 2.1. Port Assessment .....................................................................................................................................................33 -

Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution In

Open Access Austin Journal of Forensic Science and Criminology Review Article Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution in Indian Populations and its Significance in Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) - A Review Based Molecular Approach Sinha M1*, Rao IA1 and Mitra M2 1Department of Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas Abstract University, India Disaster Victim Identification is an important aspect in mass disaster cases. 2School of Studies in Anthropology, Pt. Ravishankar In India, the scenario of disaster victim identification is very challenging unlike Shukla University, India any other developing countries due to lack of any organized government firm who *Corresponding author: Sinha M, Department of can make these challenging aspects an easier way to deal with. The objective Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas University, India of this article is to bring spotlight on the potential and utility of uniparental DNA haplogroup databases in Disaster Victim Identification. Therefore, in this article Received: December 08, 2016; Accepted: January 19, we reviewed and presented the molecular studies on mitochondrial and Y- 2017; Published: January 24, 2017 chromosomal DNA haplogroup distribution in various ethnic populations from all over India that can be useful in framing a uniparental DNA haplogroup database on Indian population for Disaster Victim Identification (DVI). Keywords: Disaster Victim identification; Uniparental DNA; Haplogroup database; India Introduction with the necessity mentioned above which can reveal the fact that the human genome variation is not uniform. This inconsequential Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) is the recognized practice assertion put forward characteristics of a number of markers ranging whereby numerous individuals who have died as a result of a particular from its distribution in the genome, their power of discrimination event have their identity established through the use of scientifically and population restriction, to the sturdiness nature of markers to established procedures and methods [1]. -

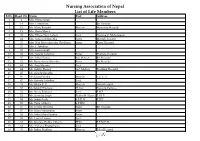

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

Some Notes on Nepali Castes and Sub-Castes—Jat and Thar

SOME NOTES ON NEPALI CASTES AND SUB-CASTES- JAT AND THAR. - Suresh Singh This paper attempts to make a re-presentation of evolution and construction of Jat and Thar system among the Parbatya or hill people of Nepal. It seeks to expose the reality behind the myth that the large number of Aryans migrated from Indian plains due to Muslim invasion and conquered to become the rulers in Nepal, and the Mongoloids were the indigenous people. It also seeks to show the construction and reconstruction of identity of the different castes (Jats) and subcastes (Thars). The Nepalese history is lost in legends and fables. Archaeological data, which might shed light on the early years, are practically nonexistent or largely unexplored, because the Nepalese Government has not encouraged such research within its borders. However, there seem to be a number of sites that might yield valuable find, once proper excavation take place. Another problem seems to be that history writing is closely connected with the traditional conception of Nepali historiography, constructed and intervened by the efforts of the ruling elite. Many of the written documents have been re-presented to legitimatize the ruling elite’s claim to power. As it is well known from political history, the social history, too, becomes an interpretation from the view of the Kathmandu valley, and from the Indian or alleged Indian immigrants and priestly class. It is difficult to imagine, that Aryans came to Nepal in greater numbers about 600 years ago, and because of their mental superiority and their noble character, they were asked by the people to become the rulers of their small states. -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

Volume 5 Issue 1 April 2017 Kathmandu School of Law Review

Volume 5 Issue 1 April 2017 Kathmandu School of Law Review 1 Volume 5 Issue 1 April 2017 Kathmandu School of Law Review China South Asia Connectivity: Reflections on Benefits of OBOR in Nepal from International Law Perspective Prof. (Dr.) Yubaraj Sangroula The Idiosyncratic History of Friendliness and Cultural Proximity in Sino- Nepal Relation An abundance of records from antiquity show that Nepal existed as a southern Himalayan state with a long an uninterrupted history of independence. The Pashupati area, with its numerous temples including the main temple dedicated to Lord Shiva, is one of the ancient locations identified with the ancient history of the nation of Nepal. As described by Dilli Raman Regmi, a noted historian of ancient Nepal, the present site of Pashupati was divided into two locations, the main temple and the surrounding area where a number of other temples surrounded the main temple. The latter location was called Deopatan, literally meaning as the city of Gods.1An adjacent location, known as Cha-bahil, which is currently known as Chabel, is of significant importance in understanding the antiquity of Nepal as a nation. Mr Regmi refers to a chronicle that describes Deopatan as a site where Magadha Emperor Ashoka, on his visit to Kathmandu, met with Nepal's King.2A legend from the Chronicle mentions that King Ashoka founded a monastery close to the north of Deopatan and left it in the care of his daughter Charumati, who married the king of Nepal.3King Ashoka ruled Maghada before 300 BCE. This historical description is evidence of two important facts about Nepal. -

Prestigious Houses Or Provisional Homes? the <I>Ghar</I> As A

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 37 Number 1 Article 11 June 2017 Prestigious Houses or Provisional Homes? The ghar as a Symbol of Kathmandu Valley Peri-Urbanism Andrew Nelson University of North Texas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Nelson, Andrew. 2017. Prestigious Houses or Provisional Homes? The ghar as a Symbol of Kathmandu Valley Peri-Urbanism. HIMALAYA 37(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol37/iss1/11 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Prestigious Houses or Provisional Homes? The ghar as a Symbol of Kathmandu Valley Peri-Urbanism Acknowledgements The author would like to thank all of the residents of Maitri Nagar for inviting him into their ghar and answering common-sense questions about what it means to them. He is also grateful to the U.S. Department of Education for sponsoring this research, as well as to Peter Moran and the Kathmandu Fulbright Office for the support extended to him while conducting research. The writing of this piece has benefitted from the helpful comments of the participants on the Kathmandu panel at the 2014 South Asian Studies Conference at Madison, as well as from insightful feedback from Heather Hindman, Melissa Nelson, Allyson Cornett, and two anonymous reviewers. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Thesis Jiri Pasz.Pdf

UTRECHT UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF GEOSCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF HUMAN GEOGRAPHY AND PLANNING INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT STUDIES MASTER OF SCIENCE THESIS The Starting Point in Life Towards inclusive birth registration in Nepal By Jiří Pasz Thesis supervised by Dr. Paul van Lindert 2011 2 Acknowledgements "Tell me, and I will forget. Show me, and I may remember. Involve me, and I will understand." Confucius The research in Nepal was one of my most valuable work and life experiences. I was amazed by the beauty of Nepal and its people. Besides being amazed, I have learned many valuable lessons, many people have influenced my life and I believe I have influenced theirs too. We have become each other’s guides and even friends during this academic adventure. I am first of all grateful to Paul van Lindert who became the mentor of my research and provided critical, yet friendly advice on all issues I had to deal with during the preparation, research and thesis writing. His input and guidance is very precious indeed and I deeply respect his wisdom and experience. Whenever we travel to another part of the world we wish to have someone there who would make ourselves feel welcome. I found such person in my Nepalese supervisor Indira Thapa. Indira not only introduced me to Plan Nepal but she was always helping me with my tasks, always keen and patient to answer my questions. I am grateful to all the other people in Plan office in Kathmandu for being so kind to me, especially to Donal Keane, Subhakar Baidya and Prem Aryal. -

A Case Study of Sarki People from Naubise Vdc of Dhading District

16 Occasional Papers, Vol 11 SOCIO-CULTURAL SUBJECTIVITIES OF LANDLESSNESS IN NEPAL: A CASE STUDY OF SARKI PEOPLE FROM NAUBISE VDC OF DHADING DISTRICT Jailab Rai * Introduction Land is a primary resource for an agrarian economy in underdeveloped countries like Nepal. More than 85 percent of Nepal’s population lives in rural areas and more than 60 percent of the economically active population is involved in agriculture (HMG, 2003). Rapid population growth and increasing pressure on land resources to earn the much needed calorie is a major challenge in the country (Graner, 1997). In this context, the study of landlessness remains an important aspect of national agenda (Shrestha, 2001), particularly in the national inclusion process (Gurung, 2006). Moreover, the study of landlessness has become a policy debate and an issue of concern in the debates on national economic development (Shrestha, 2001). The sociological and anthropological understanding of landlessness has its own importance since it requires the analysis of cultural dimensions (Caplan, 1970 and 1972) as socio-cultural subjectivities in a historical context. The access to land resources or landlessness is an important social issue, which can be linked with social and cultural aspects of landless people as socio-cultural subjectivities in drawing out the implication of their access to land resources. This study deals with the socio-cultural subjectivities of landlessness with a focus on the Sarki people in the central hills of Nepal who are among the extremely marginalized groups of people in terms of the access and ownership to land resources. It reviews the process of * Jailab Rai holds M.