COASTAL AREA MANAGEMENT in MALTA Note

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 8.10.2019 COM(2019)

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 8.10.2019 COM(2019) 463 final REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE COUNCIL 2019 report on the economic and social situation of Gozo (Malta) EN EN 2019 REPORT ON THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL SITUATION OF GOZO (MALTA) Without prejudice to the ongoing negotiations on the Multiannual Financial Framework for the period 2021-2027, and in accordance with Declaration 36 on the island region of Gozo annexed to the Treaty of Accession of Malta, the Government of Malta requested in February 2019 the Commission to report to the Council on the economic and social situation of Gozo and, in particular, on the disparities of the social and economic development levels between Gozo and Malta and to propose appropriate measures, to enable the further integration of Gozo within the internal market. This report assesses the state of development of Gozo and the evolution of disparities within Malta. It provides an assessment by reviewing recent trends on a series of dimensions and indicators relevant for the development of Gozo, i.e. demography and labour market, structure of the economy and economic growth, geography and accessibility. The paper also provides a comparison of Gozo with the rest of Malta and with other European regions. Finally, it analyses how Cohesion policy addresses the development needs of Gozo. This report uses regional statistics produced by Eurostat and by the Maltese Statistical Office. 1. ANALYSIS OF THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL SITUATION IN GOZO 1.1. Geography and land use Gozo is the second most important island of the Maltese archipelago in terms of surface and population. -

Viaggiatori Della Vita JOURNEY to MALTA: a Mediterranean Well

Viaggiatori della vita organises a JOURNEY TO MALTA: A Mediterranean well concerted lifestyle View of Valletta from Marsamxett Harbour. 1st Travel Day The tour guide (if necessary, together with the interpreter) receives the group at Malta International Airport (Luqa Airport) and accompanies it to the Hotel [first overnight stay in Malta] 2nd Travel Day The tour guide and the interpreter accompany the group to visit the main historical places of Valletta, the capital of Malta; a city guide provides background knowledge during a walk of about 1 ½ to 2 hours to the most interesting places. Leisure time and shopping tour in Valletta. [second overnight stay in Malta] Valletta Historical centre of Valletta View from the Upper Barracca Gardens to the Grand Harbour; the biggest natural harbour of Europe. View of Lower Barracca Gardens 3rd Travel Day The tour guide and the interpreter accompany the group to visit the main places worth visiting in Sliema and St. Julian's. Leisure time. [third overnight stay in Malta] Sliema, Malta. Sliema waterfront twilight St. Julian's Bay, Malta. Portomaso Tower, St. Julian's, Malta. 4th Travel Day The tour guide and the interpreter accompany the group to visit the most famous places of interest in Gozo (Victoria / Rabat, Azure Window, Fungus Rock, Blue Grotto and so forth) [fourth overnight stay in Malta] Azure Window, Gozo. Fungus Rock (the General's Rock), at Dwejra, Gozo. View from the Citadel, Victoria, capital city of Gozo. Saint Paul's Bay, Malta. 5th Travel Day Journey by coach to different localities of Malta; the tour guide and the interpreter accompany the group. -

Socioeconomic Status and Its Impact on the Prevalence of Severe ADHD in the Maltese Islands

OriginalEditorial OrgOdRe Article Socioeconomic status and its impact on the prevalence of severe ADHD in the Maltese Islands Christopher Rolé, Nigel Camilleri, Rachel Taylor-East, Neville Calleja Abstract The main aim of this study was to assess Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder whether higher prevalence rates of ADHD were (ADHD) is a common disorder which presents in present in the districts, which are classically childhood. The core symptoms include; associated with a low socioeconomic status. All hyperactivity, impulsivity and reduced attention. If persons aged 0 to 18 years attending the left untreated this may possibly lead to various governmental clinics, having a documented impairments of function in other areas of one’s life, diagnosis of severe ADHD and therefore being such as lack of educational attainment, increased prescribed pharmacotherapy were identified and risk of accident-prone behaviour, substance misuse included in this study. Nine young people were and antisocial behaviours. Although the exact living in institutional care and were therefore aetiology is still not fully understood, various excluded from statistical analysis since this would studies have demonstrated the presence of both a skew that data in this study. A significant difference genetic and an environmental component. ADHD is (p<0.0001) in the point prevalence of ADHD highly hereditable, demonstrating a strong genetic between the six Malta districts was found, with component (0.75). Furthermore, increased rates of higher rates of ADHD occurring in the harbour ADHD have been linked with a low socioeconomic districts. Though not statistically significant, a status. positive correlation was demonstrated between the The islands of Malta have traditionally been ADHD prevalence and a number of socioeconomic divided for statistical purposes into 6 districts, with variables, these included; the rate of smoking certain districts more often being associated with (p=0.111), number of people classified as at-risk-of- low socioeconomic demographics. -

The Maltese Islands: Climate, Vegetation and Landscape

A revised version of this paper has been published as: Schembri, P.J. (1997) The Maltese Islands: climate, vegetation and landscape. GeoJournal 41(2): 115-125. THE MALTESE ISLANDS: CLIMATE, VEGETATION AND LANDSCAPE by Patrick J. Schembri Department of Biology University of Malta Msida MSD 06 MALTA Abstract The Maltese Islands, situated in the central Mediterranean, occupy an area of only some 316 km2. The climate is typically Mediterranean: the average annual rainfall is c.530mm of which some 85% falls during the period October to March; the mean monthly temperature range is 12-26°C, and the islands are very windy and sunny. Although small, the Maltese Islands have a considerable diversity of landscapes and ecosystems which are representative of the range and variety of those of the Mediterranean region. The islands are composed mainly of limestones, the soils are young and are very similar to the parent rocks, and there are no mountains, streams or lakes, but only minor springs; the main geomorphological features are karstic limestone plateaux, hillsides covered with clay taluses, gently rolling limestone plains, valleys which drain runoff during the wet season, steep sea-cliffs on the south-western coasts, and gently sloping rocky shores to the Northeast. The main vegetational assemblages are maquis, garigue and steppe; minor ones include patches of woodland, coastal wetlands, sand dunes, freshwater, and rupestral communities; the latter are the most scientifically important in view of the large number of endemic species they support. Human impact is significant. Some 38% of the land area is cultivated, c.15% is built up, and the rest is countryside. -

Malta Events Guide 2018

Malta events guide 2018 cover.indd 2 05/02/2018 10:53 Malta events guide 2018 From carnivals and sporting action to fiestas and religious festivals steeped in tradition, the Maltese Islands host a year-round programme of colourful events and celebrations set against the backdrop of a warm Mediterranean Arts & Culture climate. They’re a great way of getting to know the islands’ people and culture - and visitors are always welcome Music Festivals to join in. There has never been a better time to visit with the capital Valletta being crowned European Capital of 20-22 April, Rock the City: To celebrate the European Capital of Culture, Rock the Culture 2018. Here are some of the highlights of the 400-plus events taking place this year. South is hosting a special edition of this popular annual music festival. A line-up of local and international music acts and DJs will appear at the exciting one-off event, held in Valletta. 3-6 May, Annie Mac - Lost and Found: This major visual arts 10 March-1 July, Dal-Bahar Madwarha: Theatre & Performance Four days of laid-back sunset beach parties exhibition sees large installations, performances and public Salt Pans and all-night raves. Watch headline acts at Gozo Malta’s largest interactions staged in traditional and unexpected locations across 8-17 June, Valletta Film Festival: open-air stages and catch a party boat to movie event is a lively, communal affair that the island. More than 25 artists from 15 countries are taking part. socialise at sea. Dwerja Bay Citadella Ramla Bay transforms the capital into a citywide cinema. -

SPECIAL NIGHT SERVICE Special Fares Payable

SPECIAL NIGHT SERVICE Special fares payable Low Season - approx September 15th to June 14th LOW SEASON - FRIDAYS 2300 0000 0100 0200 0300 62 Valletta to Paceville 20 62 Paceville to Valletta 30 00 49 Paceville to Bugibba, Burmarrad 00 30 118 Paceville to Vittoriosa, Birzebbugia, Gudja 00 30 134 Paceville to Paola, Zurrieq, Mqabba 00 30 881 Paceville to Siggiewi, Rabat, Dingli 00 30 LOW SEASON - SATURDAYS 2300 0000 0100 0200 0300 62 Valletta to Paceville 20 62 Paceville to Valletta 30 00 11 Paceville to Birzebbugia 00 30 00 18 Paceville to Zabbar 00 30 00 20 Paceville to Marsascala 00 30 00 29 Paceville to Zejtun 00 30 00 34 Paceville to Zurrieq and Mqabba 00 30 00 40 Paceville to Attard 00 30 00 43 Paceville to Bugibba, Mellieha 00 30 00 53 Paceville to Naxxar and Mosta 00 00 00 00 81 Paceville to Rabat, Dingli, Mtarfa 00 30 00 88 Paceville to Zebbug, Siggiewi 00 30 00 High Season - approx June 15th to September 14th HIGH SEASON - DAILY 2300 0000 0100 0200 0300 62 Valletta to Paceville 20 67 Bugibba to Paceville (route number?) 20 62 Paceville to Valletta 15 30 45 00 15 30 45 00 15 30 45 00 20 40 00 45 Paceville to Cirkewwa 10 00 00 00 00 53 Paceville to Naxxar and Mosta 00 00 00 00 HIGH SEASON - ADDITIONAL FRIDAY SERVICES 2300 0000 0100 0200 0300 118 Paceville to Vittoriosa, Birzebbugia, Gudja 00 30 00 134 Paceville to Paola, Zurrieq, Mqabba 00 30 00 881 Paceville to Siggiewi, Rabat, Dingli 00 30 00 HIGH SEASON - ADDITIONAL SATURDAY SERVICES 2300 0000 0100 0200 0300 11 Paceville to Birzebbugia 00 30 00 18 Paceville to Zabbar 00 30 00 -

ESE Accommodation Options ESE Accommodation Options

ESE Accommodation Options 2017 ESE Residence ESE Building Paceville Avenue, St. Julians STJ 3103 Tel: +356 21373789 Residence inin----househouse ESE main school building ESE Residence Amenities near by: • Bus stops • Post Office • Pharmacy • Supermarkets • Bars • Restaurants • Banks/ATM • Beaches (Rocky) • Paceville Type of accommodation : ESE Residence Other information: Local Transport Age of students: 18 years and over Towels are changed twice a week Bus stops are less than 5 mins from the Residence. 2-hour ticket costs € € Check-in any day after: 15:00 Linen changed weekly 2.00 in summer & 1.50 in winter. For more details visit: www.publictransport.com.mt Check-out any day before: 11:00 Daily maid service Travel time to school: Residence is in school building Fast Facts Available: Year round Breakfast included: Served at ‘The Cake Box’ cafeteria Number of rooms: 19 (*1 wheelchair access) in the school building Number of beds per room: 2 Reception: 24/7 (school reception) Room Types: Single & Twin Key Card (given on arrival) (Hotel rules apply when booking) Deposits and Damages Charges: Refundable deposit Each room is equipped with: of €100 on arrival, (if no damages or fines) Single or Double bed En-suite bathroom Visitors: Visitors are allowed only in reception. Television No visitors are allowed in bedrooms. Free WiFi Noise and Restrictions: Noise must be kept to a Fully air-conditioned minimum after 23:00 ESE White House Hostel White House Hostel Paceville Avenue, St. Julians STJ 3103 Tel: +356 21373789 Opposite ESE school Amenities near by: White House Hostel • Bus stops • Post Office • Pharmacy • Supermarkets • Bars • Restaurants • Banks/ATM • Beaches (Rocky) • Paceville Type of accommodation : ESE Residence Other information: Local Transport Age of students: 18 years and over Bus stops are less than 5 mins from the Residence. -

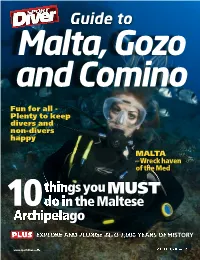

Guide to Malta, Gozo and Comino

Guide to Malta, Gozo and Comino Fun for all - Plenty to keep divers and non-divers happy MALTA –Wreck haven of the Med things you MUST 10do in the Maltese Archipelago PLUS EXPLORE AND PLUNGE INTO 7,000 YEARS OF HISTORY APRIL 2011 89 GUIDE TO GUIDE TO MALTA MALTA From the editor Knights of St. John - live in truth, have faith, repent of sins, give proof of humility, love justice, be merciful, be The Maltese archipelago has long been a firm favourite with British sincere and whole-hearted and endure persecution. divers, and for good reason – it is just over a two-and-a-half hour Take a boat trip to the Blue Grotto, which is reached flight from the UK, the water is warm and clear, the climate is hot from Wied iz-Zurrieq. This natural picturesque grotto and sunny, and the locals drive on the left. Combine this with 9and its neighbouring system of caverns mirror the accommodation to suit all budgets, myriad variety of restaurants and TOP TEN brilliant phosphorescent colours of the underwater flora. bars, not to mention a rich history and plenty of land-based Experience the traditional Maltese way of attractions for non-divers and ‘dry days’, and it is easy to see why so THINGS YOU MUST DO... life by getting away from the tourist many people flock to this part of the Mediterranean on a regular basis. 10 hotspots and exploring the fishing village of Malta is blessed with some natural underwater topography that amazes divers, such as Marsaxlokk. This is also the perfect opportunity to the Arch at Cirkewwa and the Caves at Ghar Lapsi. -

Phylogeny and Subfamilial Classification of the Grasses (Poaceae) Author(S): Grass Phylogeny Working Group, Nigel P

Phylogeny and Subfamilial Classification of the Grasses (Poaceae) Author(s): Grass Phylogeny Working Group, Nigel P. Barker, Lynn G. Clark, Jerrold I. Davis, Melvin R. Duvall, Gerald F. Guala, Catherine Hsiao, Elizabeth A. Kellogg, H. Peter Linder Source: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, Vol. 88, No. 3 (Summer, 2001), pp. 373-457 Published by: Missouri Botanical Garden Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3298585 Accessed: 06/10/2008 11:05 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mobot. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

The Genera of Bambusoideae (Gramineae) in the Southeastern United States Gordon C

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Faculty Research & Creative Activity Biological Sciences January 1988 The genera of Bambusoideae (Gramineae) in the southeastern United States Gordon C. Tucker Eastern Illinois University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/bio_fac Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Tucker, Gordon C., "The eg nera of Bambusoideae (Gramineae) in the southeastern United States" (1988). Faculty Research & Creative Activity. 181. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/bio_fac/181 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Research & Creative Activity by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TUCKER, BAMBUSOIDEAE 239 THE GENERA OF BAMBUSOIDEAE (GRAMINEAE) IN THE SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATESu GoRDON C. T ucKER3 Subfamily BAMBUSOIDEAE Ascherson & Graebner, Synop. Mitteleurop. Fl. 2: 769. 1902. Perennial or annual herbs or woody plants of tropical or temperate forests and wetlands. Rhizomes present or lacking. Stems erect or decumbent (some times rooting at the lower nodes); nodes glabrous, pubescent, or puberulent. Leaves several to many, glabrous to sparsely pubescent (microhairs bicellular); leaf sheaths about as long as the blades, open for over tf2 their length, glabrous; ligules wider than long, entire or fimbriate; blades petiolate or sessile, elliptic to linear, acute to acuminate, the primary veins parallel to-or forming an angle of 5-10• wi th-the midvein, transverse veinlets numerous, usually con spicuous, giving leaf surface a tessellate appearance; chlorenchyma not radiate (i.e., non-kranz; photosynthetic pathway C.,). -

State of Populism in Europe

2018 State of Populism in Europe The past few years have seen a surge in the public support of populist, Eurosceptical and radical parties throughout almost the entire European Union. In several countries, their popularity matches or even exceeds the level of public support of the centre-left. Even though the centre-left parties, think tanks and researchers are aware of this challenge, there is still more OF POPULISM IN EUROPE – 2018 STATE that could be done in this fi eld. There is occasional research on individual populist parties in some countries, but there is no regular overview – updated every year – how the popularity of populist parties changes in the EU Member States, where new parties appear and old ones disappear. That is the reason why FEPS and Policy Solutions have launched this series of yearbooks, entitled “State of Populism in Europe”. *** FEPS is the fi rst progressive political foundation established at the European level. Created in 2007 and co-fi nanced by the European Parliament, it aims at establishing an intellectual crossroad between social democracy and the European project. Policy Solutions is a progressive political research institute based in Budapest. Among the pre-eminent areas of its research are the investigation of how the quality of democracy evolves, the analysis of factors driving populism, and election research. Contributors : Tamás BOROS, Maria FREITAS, Gergely LAKI, Ernst STETTER STATE OF POPULISM Tamás BOROS IN EUROPE Maria FREITAS • This book is edited by FEPS with the fi nancial support of the European -

22422 AVMD Enrfrm

The Journal of the American Bamboo Society Volume 21 BAMBOO SCIENCE & CULTURE The Journal of the American Bamboo Society is published by the American Bamboo Society Copyright 2008 ISSN 0197– 3789 Bamboo Science and Culture: The Journal of the American Bamboo Society is the continuation of The Journal of the American Bamboo Society President of the Society Board of Directors Brad Salmon Brad Salmon Ned Jaquith Vice President Mike JamesLong Ned Jaquith Fu Jinhe Steve Stamper Treasurer Lennart Lundstrom Sue Turtle Daniel Fox Mike Bartholomew Secretary David King David King Ian Connor Bill Hollenback Membership William King Michael Bartholomew Cliff Sussman Steve Muzos Membership Information Membership in the American Bamboo Society and one ABS chapter is for the calendar year and includes a subscription to the bimonthly Newsletter and annual Journal. See http://www.bamboo.org for current rates or contact Michael Bartholomew, 750 Krumkill Rd. Albany NY 12203-5976. Bamboo Science and Culture: The Journal of the American Bamboo Society 21(1): 1-8 © Copyright 2008 by the American Bamboo Society Cleofé E. Calderón (1929-2007) through the extensive collections made by both Calderón and Soderstrom. Tom Soderstrom, a dynamic young curator who was just discovering the fascinating world of bamboo, invited Cleo to conduct research at the grass herbarium. At that time, Tom’s inter - est was focused on herbaceous bamboos, espe - cially those in the tribe Olyreae. Dr. Floyd McClure was working on woody bamboos in the Grass Lab at the same time, so their research was complementary. And Agnes Chase, the Honorary Curator of Grasses, was still actively curating the grass collection until shortly before her death in September of 1963, so Cleo would have met her as well.