Classic Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

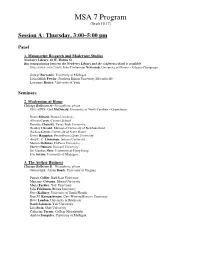

MSA 7 Program (Draft 10.17)

MSA 7 Program (Draft 10.17) Session A: Thursday, 3:00–5:00 pm Panel 1. Manuscript Research and Modernist Studies Newberry Library, 60 W. Walton St. Bus transportation between the Newberry Library and the conference hotel is available ORGANIZER AND CHAIR: John Timberman Newcomb, University of Illinois – Urbana-Champaign George Bornstein, University of Michigan Laura Milsk Fowler, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Lawrence Rainey, University of York Seminars 2. Modernism at Home Chicago Ballroom A—No auditors, please ORGANIZER: Gail McDonald, University of North Carolina – Greensboro Dawn Blizard, Brown University Allison Carey, Cannon School Dorothy Chansky, Texas Tech University Bradley Clissold, Memorial University of Newfoundland Barbara Green, University of Notre Dame Kevin Hagopian, Pennsylvania State University Amy E. C. Linneman, Indiana University Marion McInnes, DePauw University Phoebe Putnam, Harvard University Jin Xiaotian Skye, University of Hong Kong Eve Sorum, University of Michigan 3. The Author Business Chicago Ballroom B—No auditors, please ORGANIZER: Alison Booth, University of Virginia Patrick Collier, Ball State University Marianne Cotugno, Miami University Maria Fackler, Yale University Julia Friedman, Brown University Peter Kalliney, University of South Florida Kurt M. Koenigsberger, Case Western Reserve University Bette London, University of Rochester Randi Saloman, Yale University Lisa Stein, Ohio University Catherine Turner, College Misericordia Andrea Zemgulys, University of Michigan 4. Anthropological -

Pressionism,Which Was Haven't Lookedat in a Long Time," Stillgoing Strongafter Maciejunessaid "It's Interestingto See World Wari

+ aynm Feran "Precisionism in DispatchEntertainment Reporter America■ 1915-1941: ReorderingReality" N 1915, ARTISTMARcEL DUCHAMP will openSunday proclaimedthe UnitedStates and continue "thecountry of theart of the throughJuly 4 at future." the Columbus "Look atthe skyscrapers!"he Museum of Art, said"Has Europe anything to 480 E. BroadSt. show more beautifulthan these?" Tourswill begiven The Frenchman's words at noonMay 26 and focusedattention on what was June 16, and 2 p.m. e seen as auniquely American artistic May 28and June movement. 18. Call 221-6801. "Precisionismin America1915-1941: ReorderingReality" is "thefirst major study of precisionismin a long time,"said NannetteMaciejunes, seniorcurator at the ColumbusMuseum of Art. "Precisionismis verytied up withthe search for a ABoVE:The cleanlines of rural unique Americanidentity," scenes: Bucks OHmJy Barn(1918) t she said"It wasabout the " by Charles Sheeler(1883-1965) tyingof a ruralpast to the mechanicalfuture. A lot of LEFT:The forms of the machine • people in the'.20s called it agewith classicalclarity: A.ugussin 'thetrue American art.' " andNu:oletle (1923)by Charles By the timeprecisionism Demuth (1883-1935) arrived,the United States waswell on itsway froma - ruralsociety to a nationof show,which began at theMontclair Art 0 big citieswith skyscrapers Museumin New Jerseyand features andhomes withmodern works by 26 artistsfrom almost 30 I marvelssuch asvacuum institutionsand private collections. cleanersand washing "Thisshow is so criticalto us," � �es. Maciejunes said"(Ferdinand) Rowald !'!. Painters and was majora collector in thisarea. He saw photographersassociated theparallel between cubism and �� withprecisionism included precisionism, andhe collected both." iii CharlesDemuth, Morton Althoughmany works in theNew I Scharnberg,Charles Sheeler Jerseyexhibition are not availablefor the s andJoseph Stella. -

Edith Halpert & Her Artists

Telling Stories: Edith Halpert & Her Artists October 9 – December 18, 2020 Charles Sheeler (1883-1965), Home Sweet Home, 1931, conte crayon and watercolor on paper, 11 x 9 in. For Edith Halpert, no passion was merely a hobby. Inspired by the collections of artists like Elie Nadelman, Robert Laurent, and Hamilton Easter Field, Halpert’s interest in American folk art quickly became a part of the Downtown Gallery’s ethos. From the start, she furnished the gallery with folk art to highlight the “Americanness” of her artists. Halpert stated, “the fascinating thing is that folk art pulls in cultures from all over the world which we have utilized and made our own…the fascinating thing about America is that it’s the greatest conglomeration” (AAA interview, p. 172). Halpert shared her love of folk art with Charles Sheeler and curator Holger Cahill, who was the original owner of this watercolor, Home Sweet Home, 1931. The Sheelers filled their home with early American rugs and Shaker furniture, some of which are depicted in Home Sweet Home, and helped Halpert find a saltbox summer home nearby, which she also filled with folk art. As Halpert recalled years later, Sheeler joined her on trips to Bennington cemetery to look at tombstones she considered to be the “first folk art”: I used to die. I’d go to the Bennington Cemetery. Everybody thought I was a queer duck. People used to look at me. That didn’t bother me. I went to that goddamn cemetery, and I went to Bennington at least four times every summer…I’d go into that cemetery and go over those tombstones, and it’s great sculpture. -

Oral History Interview with Edith Gregor Halpert, 1965 Jan. 20

Oral history interview with Edith Gregor Halpert, 1965 Jan. 20 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview HP: HARLAN PHILLIPS EH: EDITH HALPERT HP: We're in business. EH: I have to get all those papers? HP: Let me turn her off. EH: Let met get a package of cigarettes, incidentally. [Looking over papers, correspondence, etc.] This was the same year, 1936. I quit in September. I was in Newtown; let's see, it must have been July. In those days, I had a four months vacation. It was before that. Well, in any event, sometime probably in late May, or early in June, Holger Cahill and Dorothy Miller, his wife -- they were married then, I think -- came to see me. She has a house. She inherited a house near Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and on the way back they stopped off and very excited that through Audrey McMahon he was offered a job to take charge of the WPA in Washington. He was quite scared because he had never been in charge of anything. He worked by himself as a PR for the Newark Museum for many years, and that's all he did. He sent out publicity releases that Dana gave him, or Miss Winsor, you know, told him what to say, and he was very good at it. He also got the press. -

Oral History Interview with Katherine Schmidt, 1969 December 8-15

Oral history interview with Katherine Schmidt, 1969 December 8-15 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Katherine Schmidt on December 8 & 16, 1969. The interview took place in New York City, and was conducted by Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview DECEMBER 8, 1969 [session l] PAUL CUMMINGS: Okay. It's December 8, 1969. Paul Cummings talking to Katherine Schubert. KATHERINE SCHMIDT: Schmidt. That is my professional name. I've been married twice and I've never used the name of my husband in my professional work. I've always been Katherine Schmidt. PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, could we start in 0hio and tell me something about your family and how they got there? KATHERINE SCHMIDT: Certainly. My people on both sides were German refugees of a sort. I would think you would call them from the troubles in Germany in 1848. My mother's family went to Lancaster, Ohio. My father's family went to Xenia, Ohio. When my father as a young man first started out in business and was traveling he was asked to go to see an old friend of his father's in Lancaster. And there he met my mother, and they were married. My mother then returned with him to Xenia where my sister and I were born. -

Edward Hopper's Adaptation of the American Sublime

Rhetoric and Redress: Edward Hopper‘s Adaptation of the American Sublime A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts Rachael M. Crouch August 2007 This thesis titled Rhetoric and Redress: Edward Hopper’s Adaptation of the American Sublime by RACHAEL M. CROUCH has been approved for the School of Art and the College of Fine Arts by Jeannette Klein Assistant Professor of Art History Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts Abstract CROUCH, RACHAEL M., M.F.A., August 2007, Art History Rhetoric and Redress: Hopper’s Adaptation of the American Sublime (80 pp.) Director of Thesis: Jeannette Klein The primary objective of this thesis is to introduce a new form of visual rhetoric called the “urban sublime.” The author identifies certain elements in the work of Edward Hopper that suggest a connection to earlier American landscape paintings, the pictorial conventions of which locate them within the discursive formation of the American Sublime. Further, the widespread and persistent recognition of Hopper’s images as unmistakably American, links them to the earlier landscapes on the basis of national identity construction. The thesis is comprised of four parts: First, the definitional and methodological assumptions of visual rhetoric will be addressed; part two includes an extensive discussion of the sublime and its discursive appropriation. Part three focuses on the American Sublime and its formative role in the construction of -

Knife Grinder Date: 1912-1913 Creator: Umberto Boccioni, Italian, 1882-1916 Title: Dynamism of a Soccer Player Work Type: Painting Date: 1913 Cubo-Futurism

Creator: Malevich, Kazimir, Russian, 1878- 1935 Title: Knife Grinder Date: 1912-1913 Creator: Umberto Boccioni, Italian, 1882-1916 Title: Dynamism of a Soccer Player Work Type: Painting Date: 1913 Cubo-Futurism • A common theme I have been seeing in the different Cubo- Futurism Paintings is a wide variety of color and either solid formations or a high amount of single colors blended or layered without losing the original color. I sense of movement is also very big, the Knife Grinder shows the action of grinding by a repeated image of the hand, knife, or foot on paddle to show each moment of movement. The solid shapes and designs tho individually may not seem relevant to a human figure all come together to show the act of sharpening a knife. I Love this piece because of the strong colors and repeated imagery to show the act. • In the Dynamism of a soccer player the sense of movement is sort of around and into the center, I can imagine a great play of lights and crystal clarity of the ideas of the objects moving. I almost feel like this is showing not just one moment or one movement but perhaps an entire soccer game in the scope of the 2D canvas. Creator: Demuth, Charles, 1883-1935 Title: Aucassin and Nicolette Date: 1921 Creator: Charles Demuth Title: My Egypt Work Type: Paintings Date: 1927 Precisionism • Precisionism is the idea of making an artwork of another “artwork” as in a piece of architecture , or machinery. The artist renders the structure using very geometric and precise lines and they tend to keep an element of realism in their work. -

SELLING ART in the AGE of RETAIL EXPANSION and CORPORATE PATRONAGE: ASSOCIATED AMERICAN ARTISTS and the AMERICAN ART MARKET of the 1930S and 1940S

SELLING ART IN THE AGE OF RETAIL EXPANSION AND CORPORATE PATRONAGE: ASSOCIATED AMERICAN ARTISTS AND THE AMERICAN ART MARKET OF THE 1930s AND 1940s by TIFFANY ELENA WASHINGTON Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation advisor: Anne Helmreich Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY JANUARY, 2013 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of __________Tiffany Elena Washington_________ candidate for the __Doctor of Philosophy___ degree*. (signed) _______Anne L. Helmreich________ (chair of the committee) ______Catherine B. Scallen__________ ________ Jane Glaubinger__________ ____ _ _ Renee Sentilles___________ (date) 2 April, 2012 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained herein. 2 For Julian, my amazing Matisse, and Livia, a lucky future artist’s muse. 3 Table of Contents List of figures 5 Acknowledgments 8 Abstract 11 Introduction 13 Chapter 1 46 Chapter 2 72 Chapter 3 93 Chapter 4 127 Chapter 5 155 Conclusion 202 Appendix A 205 Figures 207 Selected Bibliography 241 4 List of Figures Figure 1. Reeves Lewenthal, undated photograph. Collection of Lana Reeves. 207 Figure 2. Thomas Hart Benton, Hollywood (1937-1938). Tempera and oil on canvas mounted on panel. The Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City. 208 Figure 3. Edward T. Laning, T.R. in Panama (1939). Oil on fiberboard. Smithsonian American Art Museum. 209 Figure 4. Plan and image of Associated American Artists Gallery, 711 5th Avenue, New York City. George Nelson, The Architectural Forum. Philadelphia: Time, Inc, 1939, 349. 210 Figure 5. Thomas Hart Benton, Departure of the Joads (1939). -

Methods for Modernism: American Art, 1876-1925

METHODS FOR MODERNISM American Art, 1876-1925 METHODS FOR MODERNISM American Art, 1876-1925 Diana K. Tuite Linda J. Docherty Bowdoin College Museum of Art Brunswick, Maine This catalogue accompanies two exhibitions, Methods for Modernism: Form and Color in American Art, 1900-192$ (April 8 - July 11, 2010) and Learning to Paint: American Artists and European Art, 1876-189} (January 26 - July 11, 20io) at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine. This project is generously supported by the Yale University Art Gallery Collection- Sharing Initiative, funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; a grant from the American Art Program of the Henry Luce Foundation; an endowed fund given by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; and Bowdoin College. Design: Katie Lee, New York, New York Printer: Penmor Lithographers, Lewiston, Maine ISBN: 978-0-916606-41-1 Cover Detail: Patrick Henry Bruce, American, 1881-1936, Composition 11, ca. 1916. Gift of Collection Societe Anonyme, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut. Illustrated on page 53. Pages 8-9 Detail: John Singer Sargent, American, 1856-1925, Portrait of Elizabeth Nelson Fairchild, 1887. Museum Purchase, George Otis Hamlin Fund and Friends of the College Fund, Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Illustrated on page 18. Pages 30-31 Detail: Manierre Dawson, American, 1887-1969, Untitled, 1913. Gift of Dr. Lewis Obi, Mr. Lefferts Mabie, and Mr. Frank J. McKeown, Jr., Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut. Illustrated on page 32. Copyright © 2010 Bowdoin College Table of Contents FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Kevin Salatino LEARNING TO PAINT: 10 AMERICAN ARTISTS AND EUROPEAN ART 1876-1893 Linda J. -

Harn Museum of Art Instructional Resource: Thinking About Modernity

Harn Museum of Art Instructional Resource: Thinking about Modernity TABLE OF CONTENTS “Give Me A Wilderness or A City”: George Bellows’s Rural Life ................................................ 2 Francis Criss: Locating Monuments, Locating Modernity ............................................................ 6 Seeing Beyond: Approaches to Teaching Salvador Dalí’s Appollinaire ............................. 10 “On the Margins of Written Poetry”: Pedro Figari ......................................................................... 14 Childe Hassam: American Impressionist and Preserver of Nature ..................................... 18 Subtlety of Line: Palmer Hayden’s Quiet Activism ........................................................................ 22 Modernist Erotica: André Kertész’s Distortion #128 ................................................................... 26 Helen Levitt: In the New York City Streets ......................................................................................... 31 Happening Hats: Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Le chapeau épinglé .............................................. 35 Diego Rivera: The People’s Painter ......................................................................................................... 39 Diego Rivera: El Pintor del Pueblo ........................................................................................................... 45 Household Modernism, Domestic Arts: Tiffany’s Eighteen-Light Pond Lily Lamp .... 51 Marguerite Zorach: Modernism’s Tense Vistas .............................................................................. -

American Painting Sculpture

AMERICAN PAINTING (# SCULPTURE 1862 MoMAExh_0020_MasterChecklist THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART W. W. NORTON &? COMPANY, INC. NEW YORK PAINTINGS An asterisk before a catalog number indicates that the painting is illustrated by a plate bearing the same number. GEORGE BELLOWS Born in Columns, Ohio, 1882; died in New York, 1925. Studied under H. G. Maratta in Chicago and under Robert Henri and Kenneth Hayes Miller in New York. Taught at the Art Students' League in New York. N. A. 1913. I STAG AT SHARKEY'S, 1909 Collection The Cleveland Museum of Art *2 ELINOR, JEAN AND ANNA, '920 Collection Albright Art Gallery, Buffalo MoMAExh_0020_MasterChecklist J HILLS OF DREAM Collection Adolph Lewisohn, New York THOMAS BENTON Born in Neosho, Missouri. 1889. Studied at the Chicago Art Institute and in Paris. Has taught at Bryn Mawr and Dartmouth Colleges, the Art Students' League in New York, and New Schoo!for Social Research, New York. Murals at New School for Social Research painted in 1930. *4 AGGRESSION, 1920. One of five panels illustrating American history. Collection the Artist RALPH BLAKELOCK Born in New York, 1847; died in the Adirondacks, 1919. Self-taught. N. A. 1916_ *, MOONLIGHT, 1889 Collection Horatio S. Rubens, New York 6 EARLY MORNING, 1891 Collection Horatio S. Rubens, New York 7 AT NATURE'S MIRROR Collection The National Gallery of Art, Washington 25 PETER BLUME . R' 6 Studied at the Educational Alliance and the Art Student's League in New Born 1D ussra, 190 . York. Lives at Gaylordsville. Connecticut. *8 WHITE FACTORY Collection Wolfgang S. Schwahacher, New York ALEXANDER BROOK Born in Brooklyn, 1898.