Saint James Major C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madonna and Child with Donor

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Lippo Memmi Sienese, active 1317/1347 Madonna and Child with Donor 1325/1330 tempera on panel painted surface: 50.8 × 23.5 cm (20 × 9 1/4 in.) overall: 51.5 × 24.2 × 0.5 cm (20 1/4 × 9 1/2 × 3/16 in.) framed: 70 x 36.2 x 5.1 cm (27 9/16 x 14 1/4 x 2 in.) Andrew W. Mellon Collection 1937.1.11 ENTRY The painting’s iconography is based on the type of the Hodegetria Virgin. [1] It presents, however, a modernized version of this formula, in keeping with the “humanized” faith and sensibility of the time; instead of presenting her son to the observer as in the Byzantine model, Mary’s right hand touches his breast, thus indicating him as the predestined sacrificial lamb. As if to confirm this destiny, the child draws his mother’s hand towards him with his left hand. The gesture of his other hand, outstretched and grasping the Madonna’s veil, can be interpreted as a further reference to his Passion and death. [2] The painting probably was originally the left wing of a diptych. The half-length Madonna and Child frequently was combined with a representation of the Crucifixion, with or without the kneeling donor. In our panel, the donor, an unidentified prelate, is seen kneeling to the left of the Madonna; his position on the far left of the composition itself suggests that the panel was intended as a pendant to a matching panel to the right. -

The Collaboration of Niccolò Tegliacci and Luca Di Tommè

The Collaboration of Niccolô Tegliacci and Lúea di Tomme This page intentionally left blank J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM Publication No. 5 THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLÔ TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ BY SHERWOOD A. FEHM, JR. !973 Printed by Anderson, Ritchie & Simon Los Angeles, California THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLO TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ The economic and religious revivals which occurred in various parts of Italy during the late Middle Ages brought with them a surge of .church building and decoration. Unlike the typically collective and frequently anonymous productions of the chan- tiers and ateliers north of the Alps which were often passed over by contemporary chroniclers of the period, artistic creativity in Italy during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries documents the emergence of distinct "schools" and personalities. Nowhere is this phenomenon more apparent than in Tuscany where indi- vidual artists achieved sufficient notoriety to appear in the writ- ings of their contemporaries. For example, Dante refers to the fame of the Florentine artist Giotto, and Petrarch speaks warmly of his Sienese painter friend Simone Martini. Information regarding specific artists is, however, often l^ck- ing or fragmentary. Our principal source for this period, The Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects by Giorgio Vasari, was written more than two hundred years after Giotto's death. It provides something of what is now regarded as established fact often interspersed with folk tales and rumor. In spite of the enormous losses over the centuries, a large num- ber of paintings survived from the Dugento and Trecento. Many of these are from Central Italy, and a relatively small number ac- tually bear the signature of the artist who painted them. -

Farm Laborers' Wages in England 1208-1850

THE LONG MARCH OF HISTORY: FARM LABORERS’ WAGES IN ENGLAND 1208-1850 Gregory Clark Department of Economics UC-Davis, Davis CA 95616 [email protected] Using manuscript and secondary sources, the paper calculates real day wages for male agricultural laborers in England from 1208 to 1850. Both nominal wages and the cost of living move differently than is suggested by the famous Phelps-Brown and Hopkins series on building craftsmen. In particular farm laborers real wages were only half as much in the pre-plague years as would be implied by the PBH index. The PBH series implied that the English economy broke from the stasis of the medieval period only in the late eighteenth century. The real wage calculated here suggest that the productivity of the economy began growing from the medieval level at least a century earlier in the mid seventeenth century. INTRODUCTION The wage history of pre-industrial England is unusually well documented for a pre- industrial economy. The relative stability of English institutions after 1066, and the early development of markets, allowed a large number of documents with wages and prices to survive in the records of churches, monasteries, colleges, charities, and government. These documents have been the basis of many studies of pre-industrial wages and prices: most notably those of James E. Thorold Rogers, William Beveridge, Elizabeth Gilboy, Henry Phelps-Brown and Sheila Hopkins, Peter Bowden, and David Farmer.1 But only one of these studies, that of Phelps- Brown and Hopkins, attempted to measure real wages over the whole period. Using the wages of building craftsmen Phelps-Brown and Hopkins constructed a real wage series from 1264 to 1954 which is still widely quoted.2 This series famously established two things. -

Petrarch and Portraiture (8 Jun 18)

Petrarch and Portraiture (8 Jun 18) University of Cambridge, Old Library, Pembroke College, Cambridge, Jun 08, 2018 Ilaria Bernocchi, University of Cambridge Petrarch and Portraiture, XIV-XVI Century The symposium investigates the interplay between Petrarch's writings and later Petrarchan litera- ture with portraiture. Through his works in both Latin and in vernacular Petrarch made crucial contributions to the establishment of new models for representation and self-representation, both in literature and in the visual arts. Portraiture – the visual celebration of the individual – offers a particularly appropri- ate vantage point from which to investigate this influence. Throughout Petrarch's extensive cor- pus, the reader engages with diverse types of portraits. In De viris illustribus, for instance, Petrarch presents literary depictions of many of the most important scriptural and classical perso- nalities. The text inspired the tradition of portraits of famous men and women depicted as exam- ples of conduct in private homes and studioli, a tradition that culminated in Paolo Giovio's Musaeo of portraits on Lake Como. In the Letters and the Canzoniere, Petrarch fashions a literary portrait of his poetic alter-ego. His engagement with portraiture culminates in Rvf 77 and 78, which are dedicated to a portrait of Laura painted by Simone Martini. By weaving together the notions of literary and visual portraiture, the poet touches on issues such as the dialogue with the effigy of the beloved, the perceived conflict between the soul and the veil of appearances, and the dynamic relationship between word and image. These aspects of Petrarch's work influenced sub- sequent reflections on the limits of art and literature in representing the complex nature of the indi- vidual. -

Giotto's Fleeing Apostle

Giotto’s Fleeing Apostle PAUL BAROLSKY —In memory of Andrew Ladis Ihave previously suggested in these pages that in the Humanities, to which this journal is dedicated, the doctrine of ut pictura poesis dominates our thinking to such an extent that we often make false or over-simplified equa- tions between texts and images, even though there is never an exact identity between words, which tell, and mute im- ages, which show. The falsifying equation between text and image is a corrupting factor in what is called “iconography,” the discipline that seeks, however imperfectly, to give verbal meaning to wordless images. Texts may suggest connota- tions or implications of images, but images never render the exact denotations of these texts. I would like to suggest here a single example of such a delicate if not fragile link between text and image—a case in which the artist begins with a text but transforms it into something other than what the words of the text describe. My example is found in the art of one of the great masters in the history of European art. I speak of Giotto. Of all the personages that Giotto painted in the Scrovegni Chapel, one of the most mysterious is the forbidding, hooded figure with his back to us, who clutches a drapery in his clenched fist in the left foreground of the Arrest of Jesus (fig. 1). This ominous figure leads us down a fascinating path. In his magisterial book Giotto’s O, Andrew Ladis ob- serves that the “anonymous henchman” has in his “rigid grasp” the robe of an “inconstant and indeterminate apostle who flees . -

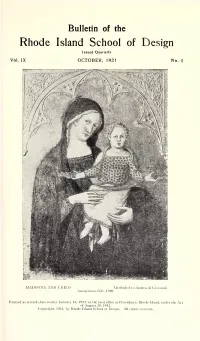

Bulletin of Rhode Island School of Design

Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design Issued Quarterly Vol. IX OCTOBER, 1921 No. 4 MADONNA AND CHILD Attributed to Andrea di Giovanni Anonymous Gift, 1920 Entered as second-class matter January 16, 1913, at the post office at Providence, Rhode Island, under the Act of August 24, 1912. Copyright, 1921, by Rhode Island School of Design. All rights reserved. IX, 34 Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design MADONNA AND CHILD, he painted in collaboration in 1372, and ATTRIBUTED TO he not infrequently repeated that master’s ANDREA DI GIOVANNI forms, though in a somewhat coarse manner. Pietro da Puccio executed in HE Rhode Island School of Design 1390 the mediocre frescoes of scenes from at Providence has acquired an ex- Genesis on the north wall of the Campo- T santo of ceptionally attractive panel picture Pisa. Of Cola da Petruccioli, of the Madonna and Child, which ap- Mr. Berenson has recently written, iden- pears at first sight to be a product of tifying this modest and not always attrac- 1 the Sienese school of the latter part of tive artist as a follower of Fei. the 14th century. No one will deny the A number of documents exist which en- Sienese character of the picture, although able us to follow the career of Andrea di closer study may suggest its attribution to Giovanni from 1370 to 1417. At the for- Andrea di Giovanni, a painter of Orvieto. mer date he was working with Cola da I recently had occasion to call attention Petruccioli and other painters, under the to the fact that even as late as the begin- direction of Ugolino da Prete Ilario, on the ing of the 15th century painting at Orvieto tribune of the Cathedral of Orvieto; but was dominated by the artistic tradition it is impossible to distinguish in these 1 of Simone Martini. -

Revisiting the Monument Fifty Years Since Panofsky’S Tomb Sculpture

REVISITING THE MONUMENT FIFTY YEARS SINCE PANOFSKY’S TOMB SCULPTURE EDITED BY ANN ADAMS JESSICA BARKER Revisiting The Monument: Fifty Years since Panofsky’s Tomb Sculpture Edited by Ann Adams and Jessica Barker With contributions by: Ann Adams Jessica Barker James Alexander Cameron Martha Dunkelman Shirin Fozi Sanne Frequin Robert Marcoux Susie Nash Geoffrey Nuttall Luca Palozzi Matthew Reeves Kim Woods Series Editor: Alixe Bovey Courtauld Books Online is published by the Research Forum of The Courtauld Institute of Art Somerset House, Strand, London WC2R 0RN © 2016, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. ISBN: 978-1-907485-06-0 Courtauld Books Online Advisory Board: Paul Binski (University of Cambridge) Thomas Crow (Institute of Fine Arts) Michael Ann Holly (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute) Courtauld Books Online is a series of scholarly books published by The Courtauld Institute of Art. The series includes research publications that emerge from Courtauld Research Forum events and Courtauld projects involving an array of outstanding scholars from art history and conservation across the world. It is an open-access series, freely available to readers to read online and to download without charge. The series has been developed in the context of research priorities of The Courtauld which emphasise the extension of knowledge in the fields of art history and conservation, and the development of new patterns of explanation. For more information contact [email protected] All chapters of this book are available for download at courtauld.ac.uk/research/courtauld-books-online Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of images reproduced in this publication. -

The Guido Riccio Controversy and Resistance to Critical Thinking

Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991) Volume 11 Issue 1 Syracuse Scholar Spring 1991 Article 5 3-21-1991 The Guido Riccio controversy and resistance to critical thinking Gordon Moran Michael Mallory Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/suscholar Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Moran, Gordon and Mallory, Michael (1991) "The Guido Riccio controversy and resistance to critical thinking," Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991): Vol. 11 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://surface.syr.edu/suscholar/vol11/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991) by an authorized editor of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moran and Mallory: The Guido Riccio controversy THE GUIDO RICCIO CONTROVERSY AND RESISTANCE TO CRITICAL THINKING GORDON MORAN and MICHAEL MALLORY HE PALAZZO PUBBLICO IN SIENA, ITALY, is decorated Twith some of Italian art's most famous murals, or frescoes. The undisputed favorite of many art lovers and of the Sienese them selves is the Guido Riccio da Fogliano at the Siege ofMontemassi (fig. 1, upper fresco), a work traditionally believed to have been painted in 1330 by Siena's most renowned master, Simone Martini. Supposedly painted at the height of the golden age of Sienese painting, the Guido Riccio fresco has come to be seen as the quintessential example of late medieval taste and the em bodiment of all that is Sienese in the art of the early decades of the four teenth century. -

Ashley Friedman ARTH155 Prof. Di Dio 2/20/14 Simone Martini's The

Ashley Friedman ARTH155 Prof. Di Dio 2/20/14 Simone Martini’s The Annunciation: A Look Into Communication Devices Simone Martini’s Annunciation, painted in 1333 for the altar of St. Ansanus in the Cathedral of Siena is one of his most treasured works. This brilliantly decorated altarpiece can now be found at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. It represents a standard in Sienese Annunciation scenes by initiating a series of paintings that follow a similar approach.1 The scene depicts the angel Gabriel kneeling in front of the Virgin Mary. There are winged seraphims surrounding a Simone Martini. The Annunciation. 1333. Uffizi Gallery, Florence. dove flying above the space in between Gabriel and Mary. Gabriel extends an olive branch as an offering of peace to Mary.2 A vase full of lilies, Mary’s iconic symbol of 1 Henk Van Os, Sienese Altarpieces, 1215-1460 (Groningen, Egbert Forseten Publishing, 1990), 99. 2 Dr. Steven Zucker, Dr. Beth Harris, “Simone Martini, Annunciation,” 4:34, Nov. 20, 2011, Khan Academy. purity rests on the marble floor in the middle of the angel and the Madonna.3 One of the most impressive aspects of this piece is the punched gold inscription which flows from the mouth of the angel Gabriel directly towards Mary, who cowers away from the angel bringing this message to her. This altarpiece was commissioned as a set of four altarpieces for the Duomo di Siena dedicated to the city’s patron saints; Savinus, Ansanus, Victor and Crescentius.4 Martini’s Annunciation was originally placed as the altarpiece for the altar of Saint Ansanus. -

PDF) 978-3-11-066078-4 E-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-065796-8

The Crisis of the 14th Century Das Mittelalter Perspektiven mediävistischer Forschung Beihefte Herausgegeben von Ingrid Baumgärtner, Stephan Conermann und Thomas Honegger Band 13 The Crisis of the 14th Century Teleconnections between Environmental and Societal Change? Edited by Martin Bauch and Gerrit Jasper Schenk Gefördert von der VolkswagenStiftung aus den Mitteln der Freigeist Fellowship „The Dantean Anomaly (1309–1321)“ / Printing costs of this volume were covered from the Freigeist Fellowship „The Dantean Anomaly 1309-1321“, funded by the Volkswagen Foundation. Die frei zugängliche digitale Publikation wurde vom Open-Access-Publikationsfonds für Monografien der Leibniz-Gemeinschaft gefördert. / Free access to the digital publication of this volume was made possible by the Open Access Publishing Fund for monographs of the Leibniz Association. Der Peer Review wird in Zusammenarbeit mit themenspezifisch ausgewählten externen Gutachterin- nen und Gutachtern sowie den Beiratsmitgliedern des Mediävistenverbands e. V. im Double-Blind-Ver- fahren durchgeführt. / The peer review is carried out in collaboration with external reviewers who have been chosen on the basis of their specialization as well as members of the advisory board of the Mediävistenverband e.V. in a double-blind review process. ISBN 978-3-11-065763-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-066078-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-065796-8 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019947596 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

![Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Peter, James Major, Anthony Abbott, and a Deacon Saint [Entire Triptych] C](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7048/madonna-and-child-with-the-blessing-christ-and-saints-peter-james-major-anthony-abbott-and-a-deacon-saint-entire-triptych-c-1997048.webp)

Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Peter, James Major, Anthony Abbott, and a Deacon Saint [Entire Triptych] C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Martino di Bartolomeo Sienese, active 1393/1434 Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Peter, James Major, Anthony Abbott, and a Deacon Saint [entire triptych] c. 1415/1420 tempera on panel Inscription: middle panel, on Christ's book: Ego S / um lu / x m / undi / [et] via / veritas / et vita / quise / gui ... (I am the light of the world and the way, the truth and the life; a conflation of John 8:12 and 14:6) [1] Gift of Samuel L. Fuller 1950.11.1.a-c ENTRY This triptych's image of the Madonna and Child recalls the type of the Glykophilousa Virgin, the “affectionate Madonna.” She rests her cheek against that of the child, who embraces her. The motif of the child’s hand grasping the hem of the neckline of the Virgin’s dress seems, on the other hand, to allude to the theme of suckling. [1] The saints portrayed are easily identifiable by their attributes: Peter by the keys, as well as by his particular facial type; James Major, by his pilgrim’s staff; Anthony Abbot, by his hospitaller habit and T-shaped staff. [2] But the identity of the deacon martyr saint remains uncertain; he is usually identified as Saint Stephen, though without good reason, as he lacks that saint’s usual attributes. Perhaps the artist did not characterize him with a specific attribute because the triptych was destined for a church dedicated to him. -

Il XXXI Dialogo Del De Remediis, Dedicato Agli Scacchi, Tavola Reale

SECRETUM MEUM ES (Familiarum Rerum XXIII 13, by Petrarch) Thou canst ill abide that others take advantage of thy labours. Do not be indignant, nor wonder at it; life is full of such mocking jests and one should not marvel at ordinary events, all the more so as it is very seldom that anything else happens. Few things serve the person who made them and most often the greater the labour, the less the reward. A short marble slab covers the founders of great cities, which are enslaved by foreigners; one man builds a house, another lives in it and its architect lies under the open sky; this man sows, that one gathers and the man who sowed dies of hunger; one sails, another becomes wealthy with the merchandise brought across the sea and the sailor is miserably poor; lastly, one weaves, another wears the cloth and the weaver is left naked; one fights, another receives the reward of victory and the true victor is left without honours, one digs up gold, another spends it and the miner is poor; another collects jewels that yet another bears upon his finger and the jeweller starves; a woman gives birth to a child amidst suffering, another happily marries him and makes him her own, to the loss of his mother. There is not enough time to list all the examples that spring to mind and what else does that well known verse of Virgil’s mean: Not for yourselves do you make nests, oh birds? Thou knowest the rest…. Thus, in 1359, Francesco exhorts his friend Socrates to bear with composure, that others profit from his labours.