UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, MERCED Novelizing the Dissent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Project 2015

PROJECT 2015 2014 E-89, 4th Floor, Hari Kothi Lane, Abul Fazal Enclave, Jamia Nagar, New Delhi - 110025 Telephone: +91 11 65377706; Mobile: +91 7042898301, 7042898311 Email: [email protected]; Website: www.hwfindia.org Report Ramadan Project 2014 Ramadan 1435 Human Welfare Foundation Report th E-89 4 Floor, Abul Fazal Enclave, Jamia Nagar Okhla, New Delhi-110025 Ramadan: “Ramadan has come to you. (It is) a month of blessing, in which Allah (swt) covers you with blessing, for He sends down mercy, decreases sins and answers prayers … … In it, Allah looks at your competition (in good deeds), and boasts about you to His angels. So show Allah goodness from yourselves.” —The Prophet Mohammed (pbuh), as narrated by Tabarani Ramadan is a blessed month of reflection, prayer and fasting for Muslims. During the month, observers gain a better understanding of and appreciation for the suffering of impoverished and hungry people around the world. Ramadan also serves to remind Muslims of the importance of charity, and their obligation to be charitable during the month and all throughout the year. VISION 2016: Food Relief Project UNDER VISION 2016, the Human Welfare Foundation distributed Iftar Kits, Sadqat Al Fitr and Eid gifts among thousands of needy families across 17 Indian States during July, which also marked the advent of Holy Month of Ramadan this year. 28,291 Iftar Kits were distributed in 17 states in India. Similarly Sadqat Al Fitr and Eid gifts were given to thousands of poor families in order to make sure that the weaker section of the society could join others in Eid celebrations. -

HU Annual Report 2018

HU Annual Report 2018 HU Annual Report 2018 HU Annual Report 2018 HU Annual Report 2018 HU Annual Report 2018 GO GREEN INITIATIVE BY HAMDARD UNIVERSITY Hamdard University has taken a Go Green Initiative on July 05, 2018. Mrs. Sadia Rasheed, Chancellor, Hamdard University, Dr. Shabib ul Hasan, Vice-Chancellor, Hamdard University, Mr. Farrukh Imad, Dean Administration, Mr. Steffen Thierfelder, Chief Executive Officer, Prettl Pro, along with Former Registrar, Deans, Directors & Staff of Hamdard University inaugurated the initiative by planting the saplings. The aim is to make our environment greener and healthier for next generations. The Hamdard University team conducted tree plantation drives in many phases. Over the last one year, Hamdard University has planted more than 1500 plants in its Main Campus, only. Tree plantation is not just something that should be done, instead, it is a necessity, the urgent need of the hour. Planting of trees is especially important to protect our environment against air pollution and global warming. To this end, our students have been actively involved in organizing tree plantation campaigns. HU Annual Report 2018 HU Annual Report 2018 Founder’s Message i Chancellor’s Message ii Vice Chancellor’s Message iii ^ Registrar’s Message i Admission Statistics 2018 7 FACULTIES Faculty of Engineering Sciences & Technology 12 Faculty of Law 30 Faculty of Eastern Medicine 46 Faculty of Management Sciences 60 Faculty of Pharmacy 68 Faculty of Social Sciences & Humanities 88 CONTENTS Faculty of Health & Medical Sciences -

Country Briefs 2011

Briefing Your Country ISP 2011 ASIA North Asia (The People’s Republic of) China (Cont.) “Delicious” in Mandarin Chinese: 好吃 (“fei chang hao chi”) or (The People’s Republic of) China 美味 (“mei wei”) Contributed by YangYi Food(s) and Drink(s): Dumplings (jiaozi); All kinds of dimsum; Cao, Haotian Wang, Spring rolls; Rice dumplings (zong zi); Fried rice; Rice cakes; Yang Zhang, Hongshan Congee; Peking duck; Green tea; Moon cakes; Soy milk; Fermented Liu, Li Guan, Yingtong and distilled alcoholic beverages; Hot pot; Steamed buns; Pork with Xie, Haisu Wang, soy sauce; Flower teas; Ginger tea; Huntun; Red pork; Steamed fish; Yangming Li, and Jian Black plum juice; White wine; Yuanxiao; Twice-cooked pork (hui Zhang guo rou); Ma po tofu; Beijing duck and Shandong pancakes in Capital: Beijing Northern China; Small steamed buns, Beef soup, Tangyuan, and Baozi in Southern China; Noodles Population: 1.3 billion Traditional Music: Chinese (i.e. Beijing, Sichuan) opera; Religion(s): Taoism; Buddhism; Christianity; Catholicism; Atheism Instrumental (i.e. bamboo flute, guzheng, erhu [a two-stringed Political Leader(s): Chairman/President Hu Jingtao; Xi Jingping; bowed instrument with a lower register than jinghu], dizi, pipa, Premier Wen Jiabao; Wu Bangguo yangqin); Kuaiban (快板); Revolutionary songs (all government workers are required to sing these songs on important Communist- Language(s): Mandarin Chinese; Cantonese; Other regional dialects party related days); Folk music; Ancient bell and drum music; The depending on the city Moon Over a Fountain; Mountain Stream; Saima (instructed by Erhu); Jasmine “Hello” in Mandarin Chinese: 你好 (“ni hao”) “Goodbye” in Mandarin Chinese: 再 (“zai jian”) 1 Briefing Your Country ISP 2011 (The People’s Republic of) China (Cont.) Hong Kong (Cont.) Sport(s): Table tennis (i.e. -

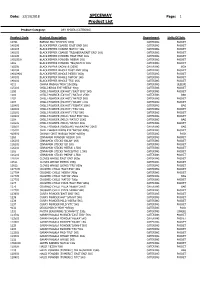

Lists Each Product and Shows the Standard Sales Price. Grouped By

Date: 22/10/2018 SPICEWAY Page: 1 Product List Product Category: DRY SPICES (CATERING) Product Code Product Description Department Units Of Sale 12391 BASSAR MIX 'TROPICS' 800g CATERING PACKET 140106 BLACK PEPPER COARSE 'EAST END' 1KG CATERING PACKET 140107 BLACK PEPPER COARSE 'NATCO' 1KG CATERING PACKET 140103 BLACK PEPPER COARSE 'TRS/HEERA/EAST END' 1KG CATERING PACKET 140105 BLACK PEPPER POWDER 'EAST END' 1KG CATERING PACKET 140105/A BLACK PEPPER POWDER 'HEERA' 1KG CATERING PACKET 1402 BLACK PEPPER POWDER 'TRS/NATCO' 1KG CATERING PACKET 150205 BLACK PEPPER SACHETS (2000) CATERING BOX 140104 BLACK PEPPER WHOLE 'EAST END' 800g CATERING PACKET 14010401 BLACK PEPPER WHOLE 'HEERA' 800g CATERING PACKET 140102 BLACK PEPPER WHOLE 'NATCO' 1KG CATERING PACKET 140101 BLACK PEPPER WHOLE 'TRS' 1KG CATERING PACKET 4111 CHANA MASALA 'MDH' 10x100g CATERING SLEEVE 125103 CHILLI BIRDS EYE 'HEERA' 400g CATERING PACKET 1200 CHILLI POWDER (EX-HOT) 'EAST END' 5KG CATERING PACKET 1203 CHILLI POWDER (EX-HOT) 'NATCO' 25KG CATERING BAG 1202 CHILLI POWDER (EX-HOT) 'NATCO' 5KG CATERING PACKET 1207 CHILLI POWDER (EX-HOT) 'RAJAH' 1 KG CATERING PACKET 120401 CHILLI POWDER (EX-HOT) 'RISHTA' 25KG CATERING BAG 120002 CHILLI POWDER (EX-HOT) 'TRS' 1KG CATERING PACKET 120201 CHILLI POWDER (EX-HOT) 'TRS' 5KG CATERING PACKET 120001 CHILLI POWDER (MILD) 'EAST END' 5KG CATERING PACKET 1204 CHILLI POWDER (MILD) 'NATCO' 25KG CATERING BAG 120202 CHILLI POWDER (MILD) 'NATCO' 5KG CATERING PACKET 120501 CHILLI POWDER (REGULAR) 'HEERA/PAK' 20KG CATERING BAG 125101 CHILLI WHOLE BIRDS -

The Significance of Fasting in Ramadan FASTING, Is Abstaining from Eating, Drinking Embarrassed, and Desist

Thursday 16 May 2019 The significance of fasting in Ramadan FASTING, is abstaining from eating, drinking embarrassed, and desist. and coitus from daybreak to sunset as a devo- The purpose of fasting is not only the tional ritual. Allah, the Almighty says in the physical training to endure hunger, thirst and Noble Quran:“O you who have believed, exhaustion; rather, it is disciplining the ego decreed upon you is fasting as it was decreed to relinquish the loved for the sake of the upon those before you that you may become Beloved. The loved are the desires of eating, righteous.” (Quran; 2:183) drinking, sexual activities etc., while the That is: that you may fear Allah, keep Beloved is Allah, the Exalted. away from His prohibitions, and fulfill His Hence, it is imperative to keep in mind Commands. Prophet Muhammad (peace be when we observe fasting that we do so only upon him) said: “Whoever does not give for the sake of Allah. It becomes imperative up forged speech and evil actions, Allah is on us to try our best to observe the rites that not in need of his leaving his food and drink reflect our obedience to Allah, such as the (i.e. Allah will not accept his fasting.)” (Al remembrance of Allah, reading the Quran, Bukhari) supererogatory prayers, charitable deeds and This means that Allah does not want us donations, good manners, etc. Fasting has to abstain from eating and drinking only, great significances and aims, which, if care- rather, He wants us to refrain from evil deeds fully considered, instill in us much surprise. -

Download Full Catalogue

BIBINA CATALOGUE INDEX Welcome to the Bibina Product Catalgoue. Due to it size the PDF document it is fully searchable. By pressing Ctrl+F (for find) on your keyboard to can search for product categories, or specific product. Due to the fact that products can only be in one category, please use the search function if you can't find the product you are searching for. Please note: Errors and omissions excepted (E&OE) ITEM CATEGORY BAKING/COOKING BISCUITS CEREAL CHEESE CHICKEN CHOCOLATES CLEANING/HOUSEHOLD CONDIMENTS/VINEGARS CONFECTIONERY DESSERT DRINKS/SYRUPS FLOURS AND MIXES FRUIT HERBS & SPICES NON STOCK NUTS OIL OLIVES PACKAGING PASTA/NOODLES PICKLED PRODUCTS RICE/COUS COUS SALT & PEPPER SEAFOOD SEASONAL SEEDS & GRAINS SMALLGOODS SNACKS SOUPS/STOCKS SPECIALTY SPREADS/SYRUPS SUGAR TEA & COFFEE TINNED/JARRED MEALS VEGETABLES VINEGAR Prices exclude gst CREATED 21/05/2021 BIBINA CATALOGUE PRODUCT LISTING BAKING/COOKING Item# Description Class Category 100602 100S AND 1000S - JAR BIBINA 300G SHELF BAKING/COOKING 104762 100S AND 1000S BIBINA 900G SHELF BAKING/COOKING 103833 100S AND 1000S GREEN - JAR BIBINA 300G SHELF BAKING/COOKING 105818 100S AND 1000S PINK - JAR BIBINA 300G SHELF BAKING/COOKING 107420 100S AND 1000S RED - JAR BIBINA 300G SHELF BAKING/COOKING 114002 BAKING POWDER BOB'S RED MILL 397G SHELF BAKING/COOKING 113619 BAKING POWDER FRUTEX 1KG SHELF BAKING/COOKING 101573 BAKING POWDER NATURE'S GROCER 1KG SHELF BAKING/COOKING 101585 BAKING POWDER PODRAVKA 5sX12G SHELF BAKING/COOKING 111528 BAKING POWDER VITAMINKA 5 PACK SHELF BAKING/COOKING -

Popat Raja & Sons Product List 2014

POPAT RAJA & SONS PRODUCT LIST 2014 AAM PAPAD, AGARBATTI, ATTA, AYURVEDIC, BAKERY, BISCUITS, BOOKS, BROOMS, CANDY, CHEESE, CHIKKI, COLD DRINK, COSMETICS, CUSTARD POWDER, DAL,DECORATION, DEHYDRATED FOODS, DRY FRUIT, ESSENCE/FOOD COLOUR, FALOODA MIX, FRYMS, GAJAK, GHEE, HEALTH DRINK, HING,HOLI/RANGOLI COLOUR, INSTANT FOOD, JAGGERY, JAMS, KHAKHRA, KIRANA, KODIYA, MANGO PULP, MILK PRODUCTS, MUKHWAS, NOODLES, OIL, PAPAD, PETHA, PICKLES, POOJA ITEMS, POOJA MURTI, RAKHI, READY TO EAT, RICE, SALT, SAUCE, SNACKS, SOUP, SPICES MASALA, SPICES POWDER, SPICES WHOLE, SPORTS, SUGAR, SWEET, SYRUP, TAMARIND, TEA/COFFEE, TOBACCO, UTENSIL, VERMICELLY, WADI. EMAIL: [email protected] ITEM NAME PACKING ITEM CODE 1 501 BAR SOAP 80 PICS X 250 GM 2 777 APPALAM 4" 75 PKTS X 200 GM 3 777 RICE VERMICILLY 20 PKTS X 500 GM 4 777 SAMBHAR POWDER 36 PKTS X 500 GM 5 A-1 VERMICELLY ROASTED (U SHAPE) 50 PKTS X 180 GM 6 A-1 VERMICELLY ROASTED (U SHAPE) 100 POUC X 150 GM 7 AAKASH ALU BHUJIA (PUDINA FLAVOUR) 50 PKTS X 200 GM 8 AAKASH ALU UPWAS CHIWDA 50 PKTS X 200 GM 9 AAKASH BADAM MIXTURE 50 PKTS X 200 GM 10 AAKASH BIKANERI BHUJIA 50 PKTS X 200 GM 11 AAKASH CHANA DAL 50 PKTS X 200 GM 12 AAKASH CORNFLAKES MIX 50 PKTS X 200 GM 13 AAKASH GARLIC SEV 50 PKTS X 200 GM 14 AAKASH INDORI BHUJIA 50 PKTS X 200 GM 15 AAKASH KAJU MIXTURE 50 PKTS X 200 GM 16 AAKASH KHATTA MITHA MIX 50 PKTS X 200 GM 17 AAKASH LAJAWAB MIX 50 PKTS X 200 GM 18 AAKASH LAUNG SEV 50 PKTS X 200 GM 19 AAKASH MASTANA MIX 50 PKTS X 200 GM 20 AAKASH MOONG DAL 50 PKTS X 200 GM 21 AAKASH MUMBAI MIX 50 PKTS X -

Merk Omschrijving a Wendjoe a Wendjoe Ketjap 750Ml a Wendjoe A

Merk Omschrijving A wendjoe A wendjoe Ketjap 750Ml A wendjoe A wendjoe Ketjap 750Ml Aashirvaad Aashirwaad Atta Export Pack 10Kg Aashirvaad Aashirvaad Atta 20x1Kg Aashirvaad Aashirvaad Multigrain Atta 20X1Kg ABC ABC Sweet Soysauce Hot Pedas 24x275 Ml ABC ABC Sambal Asli 24x335Ml ABC ABC Sambal Extra Hot 24x335Ml ABC ABC Sweet Soysauce (PET) 12x600ml ABC ABC Original Chilli Sauce 24x335 ml Ace Ace Vitamin Drink 6x500Ml AFP AFP Fioretto White Maize Flour(Green) 1Kg African Beauty African Beauty Palm Oil 1Ltr Ahmed Ahmed Mix Pickle 1Kg Ahmed Ahmed Mango Pickle 12x330G Ajinomoto Ajinomoto 10Kg Ajinomoto Aji-No-Moto (S) 85g Ajwa Ajwa Basmati Rice 5Kg Akash Akash Basmati Rice 1Kg Akash Akash Basmati Rice 2Kg Akfa Akfa Tomato Puree 12x850g Allaman's Allaman's Pomtayer 24x1Kg Ambala Ambala Maida(White Atta) 25Kg Ambala Ambala Chapati Atta Flour 25Kg Ambition Coconut Powder 1Kg Ambition Ambition Garlic Flakes 1Kg Ambition Ambition Garlic Powder 1Kg Ambition Ambition Coconut Powder 500G Ambition Ambition Ginger Powder 1Kg Ambition Ambition Chinese Champignons Po-Ku (Blik) 284G Ambition Ambition Finest Creamed Coconut(Santen) 40x7Oz Ambition Ambition Chinese Gember Stem Shavings(Pot) 450G Ambition Ambition Koreaanse Oesters Whole in Water(Blik) 225G Ambition Ambition Chinese Lychee In Syrup(Blik) 567G Ambition Ambition Chinese Gember Stem Small Nuts(Pot) 450G Amidhara Amidhara Mango Pulp Kesar 6x850Ml Amigo Amigo Longain Rice 20KG Annam Annam Tapioca Sabudana(B) 20x300G Annam Annam Unroasted Rawa(Suji) 1Kg Annam Annam Upma Rawa 1Kg Annam Annam Urid -

Conflict and Social Media: Activism of Civil Society for Peace Between India-Pakistan

Policy Brief No. 20 APLN/CNND 1 Policy Brief No. 70 March 2020 Conflict and Social Media: Activism of Civil Society for Peace Between India-Pakistan Qamar Jafri Summary This policy brief examines the work of civil society activists struggling for peace by using social media around the world. Drawing from extensive field research, as well as the social media actions of activists and civil society members of India, Pakistan and beyond, this brief explains how the social media strategies of civil society activists can ease the risk of war and violence and improve the prospect for long-term peaceful relations between both countries. The South Asia region, including Afghanistan, India and Pakistan, has been known for intractable regional conflict. The conflict between India and Pakistan over Kashmir led to four wars (1948, 1965, 1971, and 1999) between these countries. Although peace efforts on the part of civil society activists have existed for many years, civil society’s use of social media for peace between both the countries is a new trend. This policy brief endeavours to add new insights on civil society’s use of social media to support peace. The brief also looks at how the civil society members deploy innovative strategies of communication—mixing social media and other methods—to plan, coordinate and practice actions, such as protests, talks, and marches. This policy brief attempts to enhance existing dimensions to the ques- tion of how to respond to the rising conflicts between nuclear countries India and Pakistan – an issue that can no longer remain unnoticed by members of civil society and the interna- tional community. -

Spicy Oriental Foods S.L. C/ Cromo No

SPICY ORIENTAL FOODS S.L. C/ CROMO NO. 87 E – 08907 ; L'HOSPITALET DE LLOBREGAT , BARCELONA TEL.: + 34 93 264 15 36 FAX.: + 34 93 263 36 91 MOBILE: + 34 677 534 870 ( Mr. Anuj Kum www.gftonline.de [email protected] ART. NO. DESPRIPTION SIZE PACKING 24051 AGARBATTI AGRA MAGIC & HOLDER 6 TUBES 24000 AGARBATTI BHARATH MATHARAM 12 PKTS 24001 AGARBATTI BHARATH MATHARAM - CTN. 288 PKTS 24002 AGARBATTI FIVE ROSE 12 25 G 24004 AGARBATTI FIVE ROSE - CTN. 144 25G 24007 AGARBATTI GATEWAY OF INDIA 12 25G 24008 AGARBATTI GATEWAY OF INDIA - CTN. 144 25G 24017 AGARBATTI METRO MILAN 12 TUBES 24018 AGARBATTI METRO MILAN - CTN. 300 TUBES 24053 AGARBATTI MUKESH 3 IN 1 12 20ST 24054 AGARBATTI MUKESH 5 IN 1 6 50ST 24052 AGARBATTI MUKESH ELEGANT 12 20ST 24031 AGARBATTI NAG CHAMPA 12 15G 24032 AGARBATTI NAG CHAMPA 12 40G 24055 AGARBATTI NAG CHAMPA - 8STK 1 25BX 24056 AGARBATTI NAG CHAMPA - 8STK 50 25BX 24033 AGARBATTI NAG CHAMPA - CTN. 600 15G 24035 AGARBATTI NIGHT QUEEN 12 20G 24036 AGARBATTI NIGHT QUEEN - CTN. 144 20G 24039 AGARBATTI SANDAL 12 PKTS 24040 AGARBATTI SANDAL - CTN. 144 PKTS 24041 AGARBATTI SEVEN JASMIN 12 TUBES 24021 AGARBATTI SREE BALAJI SAI 4 IN 1 12 PKT 24022 AGARBATTI SREE BALAJI SAI 4 IN 1 -CTN. 288 PKT 79774 AGARBATTI SUGANDHA SHRINGAR 12 LGE 79773 AGARBATTI SUGANDHA SHRINGAR-CTN. 144 LGE 24013 AGARBATTI SUPER SANDAL 12 PKT 24014 AGARBATTI SUPER SANDAL - CTN. 288 PKT 24047 AGARBATTI THREE IN ONE 12 PKTS 24048 AGARBATTI THREE IN ONE - CTN. 300 PKTS 24049 AGARBATTI THREE ROSE 12 25G 24050 AGARBATTI THREE ROSE 144 25G 54848 AGARBATTI TWO IN ONE 12 PKTS 54849 AGARBATTI TWO IN ONE - CTN. -

Vegetable Pakoras 4 Veggie Samosas 4 Beef Samosas 5 Beef Shami Kabob 6 Chicken Tikka Boti Kabob 10 Beef Tikka Boti Kabob 11 Beef

with basmati rice, please order bread separately Chicken Tikka Masala 10 boneless chicken cooked with tomatoes, garlic, but- ter, cream, and spices Chicken Jalfrezi 10 boneless chicken curried with bell peppers, fresh vegetables, and spices The Bala family’s ancestry originates in the fertile farmlands of India. Here a cuisine that Beef Korma 10 fused vibrant spices with meats cooked in a boneless beef cooked with yogurt, tomatoes, onion, traditional clay oven was perfected. After the and topped with almonds partition of India in 1947, the Bala family Lamb Vindaloo 13 carried their prized recipes to the newly formed boneless lamb cooked with vinegar, potatoes, onion, country of Pakistan. and spices Several years later, Shabbir and Ruqayya Bala 11 immigrated to the United States where they Jingha Masala shrimp curried with cream, coconut, onion, garlic, now are proud to introduce the exotic flavors ginger, and spices and unique cuisine of Pakistan and India to Marysville, Washington. Boondockers now Chili Chicken 10 features affordable succulent kabobs, savory boneless chicken curried with chilies, tomato, onion, curries, buttery breads, and much more. garlic, and spices Daal 10 lentil of the day creamed with spices Mixed Vegetable Curry 10 served with chutney seasonal vegetables curried with yogurt and spices Vegetable Pakoras 4 vegetable fritters dipped in chickpea flour and fried golden brown Roti 2 Veggie Samosas 4 two thin breads triangular pastry filled with seasoned potatoes and Paratha 2 vegetables or meat flaky crispy bread brushed -

01 Cuisine of Jammu and Kashmir and Himachal

Regional Cuisines of India-I BHM-502AT UNIT: 01 CUISINE OF JAMMU AND KASHMIR AND HIMACHAL STRUCTURE 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Objectives 1.3 Jammu and Kashmir 1.3.1 Geographical Perspectives 1.3.2 Brief Historical Background 1.3.3 Climate 1.3.4 Agriculture and Staple Food 1.3.5 Characteristics & Salient Features of Cuisine 1.3.6 Equipments and Utensils Used 1.3.7 Specialties during Festivals and Other Occasions 1.3.8 Festivals and Other Occasions 1.3.9 A Kashmiri Kitchen during Festivals 1.3.10 Dishes from Kashmiri Cuisine 1.4 Himachal Pradesh 1.4.1 Geographical Perspectives 1.4.2 Brief Historical Background 1.4.3 Climate 1.4.4 Agriculture and Staple Food 1.4.5 Characteristics and Salient Features Of The Cuisine 1.4.6 Cooking Equipments 1.4.7 Specialties during Festivals and Other Occasions 1.4.8 Community Meals 1.4.9 Festivals and Other Occasions 1.4.10 Dishes from Himachali Cuisine 1.5 Summary 1.6 Glossary 1.7 Reference/Bibliography 1.8 Terminal Questions 1.1 INTRODUCTION This part of Northern India comprises Jam mu, Kashmir Leh and Ladakh. It is the most enchanting state, with its' snow-capped Himalayan ranger, beautiful lakes and houseboats is often called the Switzerland in India. This area experiences extreme climate, summers are cool where as winters are cold and snowy and even frosty. Being bordered by the mighty Himalayas in the north, some of the areas in these states are covered with snow throughout the year. Northern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows cover more than Uttarakhand Open University 1 Regional Cuisines of India-I BHM-502AT 49,400 square kilometers (19,100 sq mi) at elevations between 3,300 and 3,600 meters (10,800 and 11,800 ft) and at the base lies the Terai- Duar savanna and grasslands.