Unveiling the Unspoken

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Law College University of the Punjab, Lahore

1 University Law College University of the Punjab, Lahore. Result of Entry Test of LL.B 03 Years Morning/Afternoon Program Session (2018-2019) (Annual System) held on 12-08-2018* Total Marks: 80 Roll No. Name of Candidate Father's Name Marks 1 Nusrat Mushtaq Mushtaq Ahmed 16 2 Usman Waqas Mohammad Raouf 44 3 Ali Hassan Fayyaz Akhtar 25 4 Muneeb Ahmad Saeed Ahmad 44 5 Sajid Ali Muhammad Aslam 30 6 Muhammad Iqbal Irshad Hussain 23 7 Ameen Babar Abid Hussain Babar Absent 8 Mohsin Jamil Muhammad Jamil 24 9 Syeda Dur e Najaf Bukhari Muhammad Noor ul Ain Bukhari Absent 10 Ihtisham Haider Haji Muhammad Afzal 20 11 Muhammad Nazim Saeed Ahmad 30 12 Muhammad Wajid Abdul Waheed 22 13 Ashiq Hussain Ghulam Hussain 14 14 Abdullah Muzafar Ali 35 15 Naoman Khan Muhammad Ramzan 33 16 Abdullah Masaud Masaud Ahmad Yazdani 30 17 Muhammad Hashim Nadeem Mirza Nadeem Akhtar 39 18 Muhammad Afzaal Muhammad Arshad 13 19 Muhammad Hamza Tahir Nazeer Absent 20 Abdul Ghaffar Muhammad Majeed 19 21 Adeel Jan Ashfaq Muhammad Ashfaq 24 22 Rashid Bashir Bashir Ahmad 35 23 Touseef Akhtar Khursheed Muhammad Akhtar 42 24 Usama Nisar Nisar Ahmad 17 25 Haider Ali Zulfiqar Ali 26 26 Zeeshan Ahmed Sultan Ahmed 28 27 Hafiz Muhammad Asim Muhammad Hanif 32 28 Fatima Maqsood Maqsood Ahmad 12 29 Abdul Waheed Haji Musa Khan 16 30 Simran Shakeel Ahmad 28 31 Muhammad Sami Ullah Muhammad Shoaib 35 32 Muhammad Sajjad Shoukat Ali 27 33 Muhammad Usman Iqbal Allah Ditta Urf M. Iqbal 27 34 Noreen Shahzadi Muhammad Ramzan 19 35 Salman Younas Muhammad Younas Malik 25 36 Zain Ul Abidin Muhammad Aslam 21 37 Muhammad Zaigham Faheem Muhammad Arif 32 38 Shahid Ali Asghar Ali 37 39 Abu Bakar Jameel M. -

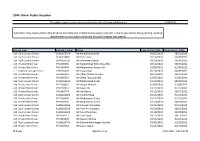

Private Hire and Hackney Carriage Driver Public Register

DPR- Driver Public Register This public register report was correct on the date of being published on 11/08/2021 Data which may display either a blank licence start date and, or blank licence expiry date, this is due to applications being pending, awaiting determination or not issued at the time this public register was created Licence type Licence number Name Licence Start Date Licence Expiry Date L06 Dual Licence Driver DUAL163354 Mr Muhammad Sajid 01/03/2019 28/02/2022 L06 Dual Licence Driver DUAL159861 Mr Zafar Iqbal 01/10/2018 30/09/2021 L06 Dual Licence Driver DUAL160322 Mr Shameem Azeem 01/10/2018 30/09/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160405 Mr Mohammad Rafiq Choudhry 01/10/2018 30/09/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160438 Mr Mohammed Kurban Ali 01/09/2018 31/08/2021 LL1 Hackney Carriage Driver HCD160418 Mr Liaqat Raja 01/10/2018 30/09/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160459 Mr Aftab Ahmed Hussain 04/10/2018 30/09/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160522 Mr Zahid Farooq Bhatti 12/09/2018 31/08/2021 L06 Dual Licence Driver DUAL160615 Mr Mohammad Ansar 01/10/2018 30/09/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160601 Mr Waqar Ahmed 01/09/2018 31/08/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160607 Mr Sajaid Ali 01/11/2018 31/10/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160774 Mr Gul Hayat 01/10/2018 30/09/2021 L06 Dual Licence Driver DUAL160623 Mr Syed Ali Raza 01/11/2018 31/10/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160630 Mr Mohammed Sadiq 01/11/2018 31/10/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160636 Mr Mohammad Hanif 01/10/2018 30/09/2021 L06 Dual Licence Driver DUAL160633 Mr -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known. -

Credentialed Staff JHHS

FacCode Name Degree Status_category DeptDiv HCGH Abbas , Syed Qasim MD Consulting Staff Medicine HCGH Abdi , Tsion MD MPH Consulting Staff Medicine Gastroenterology HCGH Abernathy Jr, Thomas W MD Consulting Staff Medicine Gastroenterology HCGH Aboderin , Olufunlola Modupe MD Contract Physician Pediatrics HCGH Adams , Melanie Little MD Consulting Staff Medicine HCGH Adams , Scott McDowell MD Active Staff Orthopedic Surgery HCGH Adkins , Lisa Lister CRNP Nurse Practitioner Medicine HCGH Afzal , Melinda Elisa DO Active Staff Obstetrics and Gynecology HCGH Agbor-Enoh , Sean MD PhD Active Staff Medicine Pulmonary Disease & Critical Care Medicine HCGH Agcaoili , Cecily Marie L MD Affiliate Staff Medicine HCGH Aggarwal , Sanjay Kumar MD Active Staff Pediatrics HCGH Aguilar , Antonio PA-C Physician Assistant Emergency Medicine HCGH Ahad , Ahmad Waqas MBBS Active Staff Surgery General Surgery HCGH Ahmar , Corinne Abdallah MD Active Staff Medicine HCGH Ahmed , Mohammed Shafeeq MD MBA Active Staff Obstetrics and Gynecology HCGH Ahn , Edward Sanghoon MD Courtesy Staff Surgery Neurosurgery HCGH Ahn , Hyo S MD Consulting Staff Diagnostic Imaging HCGH Ahn , Sungkee S MD Active Staff Diagnostic Imaging HCGH Ahuja , Kanwaljit Singh MD Consulting Staff Medicine Neurology HCGH Ahuja , Sarina MD Consulting Staff Medicine HCGH Aina , Abimbola MD Active Staff Obstetrics and Gynecology HCGH Ajayi , Tokunbo Opeyemi MD Active Staff Medicine Internal Medicine HCGH Akenroye , Ayobami Tolulope MBChB MPH Active Staff Medicine Internal Medicine HCGH Akhter , Mahbuba -

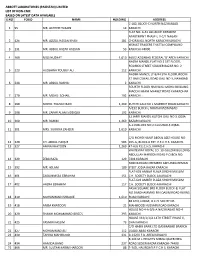

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

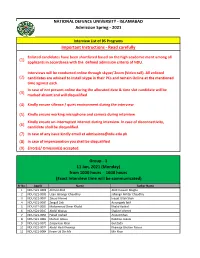

Interview Panel List (For Admission Staff)

NATIONAL DEFENCE UNIVERSITY - ISLAMABAD Admission Spring - 2021 Interview List of BS Programs Important Instructions - Read carefully Enlisted candidates have been shortlisted based on the high academic merit among all (1) applicants in accordance with the defined admission criteria of NDU. Interviews will be conducted online through skype/ Zoom (Video call). All enlisted (2) candidates are advised to install skype in their PCs and remain Online at the mentioned time against each. In case of not present online during the allocated date & time slot candidate will be (3) marked absent and will disqualified (4) Kindly ensure silience / quiet environment during the interview (5) Kindly ensure working microphone and camera during interview Kindly ensure un-interrupted internet during interview. In case of disconnectivity, (6) candidate shall be disqualified. (7) In case of any issue kindly email at [email protected] (8) In case of impersonation you shall be disqualified (9) Error(s)/ Omission(s) accepted. Group - 1 11 Jan, 2021 (Monday) from 1000 hours - 1600 hours (Exact Interview time will be communicated) Sr No. AppID Name Father Name 1 NDU-S21-0008 Ahmed Abid Abid Hussain Mughal 2 NDU-S21-0030 Uzair Jahangir Chaudhry Jahangir Akhtar Chaudhry 3 NDU-S21-0034 Zabad Ahmed Inayat Ullah Shah 4 NDU-S21-0037 Zergull Zeb Aurangzeb latif 5 NDU-S21-0039 Mohammad Omer Khalid Khalid Rashid 6 NDU-S21-0047 Abdul Wassay Shakeel Ahmed 7 NDU-S21-0059 Fahad Arshad Arshad Khan 8 NDU-S21-0062 Mohsin Abbas Rabdino Jiskani 9 NDU-S21-0073 Zulqarnain Khan -

The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2021

PERSONS • OF THE YEAR • The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • B The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • i The Muslim 500: The World’s 500 Most Influential Chief Editor: Prof S Abdallah Schleifer Muslims, 2021 Editor: Dr Tarek Elgawhary ISBN: print: 978-9957-635-57-2 Managing Editor: Mr Aftab Ahmed e-book: 978-9957-635-56-5 Editorial Board: Dr Minwer Al-Meheid, Mr Moustafa Jordan National Library Elqabbany, and Ms Zeinab Asfour Deposit No: 2020/10/4503 Researchers: Lamya Al-Khraisha, Moustafa Elqabbany, © 2020 The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre Zeinab Asfour, Noora Chahine, and M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin 20 Sa’ed Bino Road, Dabuq PO BOX 950361 Typeset by: Haji M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin Amman 11195, JORDAN www.rissc.jo All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanic, including photocopying or recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily reflect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Set in Garamond Premiere Pro Printed in The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Calligraphy used throughout the book provided courte- sy of www.FreeIslamicCalligraphy.com Title page Bismilla by Mothana Al-Obaydi MABDA • Contents • INTRODUCTION 1 Persons of the Year - 2021 5 A Selected Surveyof the Muslim World 7 COVID-19 Special Report: Covid-19 Comparing International Policy Effectiveness 25 THE HOUSE OF ISLAM 49 THE -

Pakistan Response Towards Terrorism: a Case Study of Musharraf Regime

PAKISTAN RESPONSE TOWARDS TERRORISM: A CASE STUDY OF MUSHARRAF REGIME By: SHABANA FAYYAZ A thesis Submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Political Science and International Studies The University of Birmingham May 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The ranging course of terrorism banishing peace and security prospects of today’s Pakistan is seen as a domestic effluent of its own flawed policies, bad governance, and lack of social justice and rule of law in society and widening gulf of trust between the rulers and the ruled. The study focused on policies and performance of the Musharraf government since assuming the mantle of front ranking ally of the United States in its so called ‘war on terror’. The causes of reversal of pre nine-eleven position on Afghanistan and support of its Taliban’s rulers are examined in the light of the geo-strategic compulsions of that crucial time and the structural weakness of military rule that needed external props for legitimacy. The flaws of the response to the terrorist challenges are traced to its total dependence on the hard option to the total neglect of the human factor from which the thesis develops its argument for a holistic approach to security in which the people occupy a central position. -

64 Pakistani Artists, 30 and Under

FRESH! 64 Pakistani Artists, 30 and Under Amin Gulgee Gallery Karachi March 2014 Curated by Raania Azam Khan Durrani Saba Iqbal Amin Gulgee Amin Gulgee Gallery Amin Gulgee launched the Amin Gulgee Gallery in the spring of 2002, was titled Uraan and in 2000 with an exhibition of his own sculpture, was co-curated by art historian and founding Open Studio III. The artist continues to display editor of NuktaArt Niilofur Farrukh and gallerist his work in the Gallery, but he also sees the Saira Irshad. A thoughtful, catalogued survey need to provide a space for large-scale and of current trends in Pakistani art, this was an thematic exhibitions of both Pakistani and exhibition of 100 paintings, sculptures and foreign artists. The Amin Gulgee Gallery is a ceramic pieces by 33 national artists. space open to new ideas and different points of view. Later that year, Amin Gulgee himself took up the curatorial baton with Dish Dhamaka, The Gallery’s second show took place in an exhibition of works by 22 Karachi-based January 2001. It represented the work created artists focusing on that ubiquitous symbol by 12 artists from Pakistan and 10 artists of globalization: the satellite dish. This show from abroad during a two-week workshop in highlighted the complexities, hopes, intrusions Baluchistan. The local artists came from all and sheer vexing power inherent in the over Pakistan; the foreign artists came from production and use of new technologies. countries as diverse as Nigeria, Holland, the US, China and Egypt. This was the inaugural In 2003, Amin Gulgee presented another major show of Vasl, an artist-led initiative that is part exhibition of his sculpture at the Gallery, titled of a network of workshops under the umbrella Charbagh: Open Studio IV. -

KARACHI BIENNALE CATALOGUE OCT 22 – NOV 5, 2017 KB17 Karachi Biennale Catalogue First Published in Pakistan in 2019 by KBT in Association with Markings Publishing

KB17 KARACHI BIENNALE CATALOGUE OCT 22 – NOV 5, 2017 KB17 Karachi Biennale Catalogue First published in Pakistan in 2019 by KBT in association with Markings Publishing KB17 Catalogue Committee Niilofur Farrukh, Chair John McCarry Amin Gulgee Aquila Ismail Catalogue Team Umme Hani Imani, Editor Rabia Saeed Akhtar, Assistant Editor Mahwish Rizvi, Design and Layouts Tuba Arshad, Cover Design Raisa Vayani, Coordination with Publishers Keith Pinto, Photo Editor Halima Sadia, KB17 Campaign Design and Guidelines (Eye-Element on Cover) Photography Credits Humayun Memon, Artists’ Works, Performances, and Venues Ali Khurshid, Artists’ Works and Performances Danish Khan, Artists’ Works and Events Jamal Ashiqain, Artists’ Works and Events Qamar Bana, Workshops and Venues Samra Zamir, Venues and Events ©All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval system - without written permission of Karachi Biennale Trust ISBN Printed by Le Topical [email protected] [email protected] www.markings.com.pk Claremont House FOREWORD Sitaron say agay jehan aur bhi hain Abhi Ishaq kay imtehan aur bhi hain Many new worlds lie beyond the stars And many more challenges for the passionate and the spirited Allama Iqbal Artists with insight and passion have always re- by the state, have begun to shrink and many imagined the world to inspire fresh beginnings with turning points in Pakistan’s art remain uncelebrated hope. Sadequain communicated through public as they are absent from the national cultural murals, Bashir Mirza furthered the discourse with discourse. -

Copy of Diamer Bhasha Dam 07-08-2018

Debit account description Current amount Debtor name Debtor account number Creditor name Creditor account number AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 20.00 UMAR UMAR AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 400.00 DANISH DANISH AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 500.00 ADC ADC AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 500.00 KUMAIL KUMAIL AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 1,000.00 ADC ADC AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 1,000.00 ADC ADC AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 1,000.00 NABEEL NABEEL AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 1,000.00 ALEEM ALEEM AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 1,250.00 ZEESHAN ZEESHAN AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 2,000.00 ADC ADC AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 2,000.00 AMJAD AMJAD AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 2,000.00 SHAHID SHAHID AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 4,000.00 ADNAN ADNAN AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 5,000.00 TAHIR TAHIR AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 7,000.00 ABDUL QADEER ABDUL QADEER AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 10,000.00 IBRAR IDREES IBRAR IDREES AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 10,000.00 AMIR AMIR AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 46,000.00 ABDUL BARI KHAN ABDUL BARI KHAN AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD 50,000.00 MUHAMMAD ABRAR MUHAMMAD ABRAR Allied Bank Limited 0.50 SAFEER ULLAH SAFEER ULLAH Allied Bank Limited 10.00 ABDUL QAYYUM ABDUL QAYYUM Allied Bank Limited 15.00 FAHD TALHAT FAHD TALHAT Allied Bank Limited 20.00 MUHAMMAD ALI REHMAN MUHAMMAD ALI REHMAN Allied Bank Limited 30.00 ALI ABDULLAH JILANI ALI ABDULLAH JILANI Allied Bank Limited 50.00 NOMAN NOMAN Allied Bank Limited 50.00 SARFRAZ UMER SARFRAZ UMER Allied Bank Limited 50.00 SYED ALI HASSAN SYED ALI