Project of Support to the National Time Bound Programme on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Institute of Business Administration, Karachi Bba, Bs

FINAL RESULT - FALL 2020 ROUND 1 Announced on Tuesday, February 25, 2020 INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, KARACHI BBA, BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE), BS (ECONOMICS) & BS (SOCIAL SCIENCES) ADMISSIONS TEST HELD ON SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2020 (FALL 2020, ROUND 1) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION (BSAF PROGRAM) SAT Test Math Eng TOTAL Maximum Marks 800 800 1600 Cut-Off Marks 600 600 1410 Math Eng Total IBA Test MCQ MCQ MCQ Maximum Marks 180 180 360 Cut-Off Marks 100 100 256 Seat S. No. App No. Name Father's Name No. 1 18 845 FABIHA SHAHID SHAHIDSIDDIQUI 132 136 268 2 549 1510 MUHAMMAD QASIM MAHMOOD AKHTAR 148 132 280 3 558 426 MUHAMMAD MUTAHIR ABBAS AMAR ABBAS 144 128 272 4 563 2182 ALI ABDULLAH MUHAMMAD ASLAM 136 128 264 5 1272 757 MUHAMMAD DANISH NADEEM MUHAMMAD NADEEM TAHIR 136 128 264 6 2001 1 MUHAMMAD JAWWAD HABIB MUHAMMAD NADIR HABIB 160 100 260 7 2047 118 MUHAMMAD ANAS LIAQUAT ALI 148 128 276 8 2050 125 HAFSA AZIZ AZIZAHMED 128 136 264 9 2056 139 MUHAMMAD SALMAN ANWAR MUHAMMAD ANWAR 156 132 288 10 2086 224 MOHAMMAD BADRUDDIN RIND BALOCH BAHAUDDIN BALOCH 144 112 256 11 2089 227 AHSAN KAMAL LAGHARI GHULAM ALI LAGHARI 136 160 296 12 2098 247 SYED MUHAMMAD RAED SYED MUJTABA NADEEM 152 132 284 13 2121 304 AREEB AHMED BAIG ILHAQAHMED BAIG 108 152 260 14 2150 379 SHAHERBANO ‐ ABDULSAMAD SURAHIO 148 124 272 15 2158 389 AIMEN ATIQ SYED ATIQ UR REHMAN 148 124 272 16 2194 463 MUHAMMAD SAAD MUHAMMAD ABBAS 152 136 288 17 2203 481 FARAZ NAWAZ MUHAMMAD NAWAZ 132 128 260 18 2210 495 HASNAIN IRFAN IRFAN ABDULAZIZ 128 132 260 19 2230 -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known. -

Credentialed Staff JHHS

FacCode Name Degree Status_category DeptDiv HCGH Abbas , Syed Qasim MD Consulting Staff Medicine HCGH Abdi , Tsion MD MPH Consulting Staff Medicine Gastroenterology HCGH Abernathy Jr, Thomas W MD Consulting Staff Medicine Gastroenterology HCGH Aboderin , Olufunlola Modupe MD Contract Physician Pediatrics HCGH Adams , Melanie Little MD Consulting Staff Medicine HCGH Adams , Scott McDowell MD Active Staff Orthopedic Surgery HCGH Adkins , Lisa Lister CRNP Nurse Practitioner Medicine HCGH Afzal , Melinda Elisa DO Active Staff Obstetrics and Gynecology HCGH Agbor-Enoh , Sean MD PhD Active Staff Medicine Pulmonary Disease & Critical Care Medicine HCGH Agcaoili , Cecily Marie L MD Affiliate Staff Medicine HCGH Aggarwal , Sanjay Kumar MD Active Staff Pediatrics HCGH Aguilar , Antonio PA-C Physician Assistant Emergency Medicine HCGH Ahad , Ahmad Waqas MBBS Active Staff Surgery General Surgery HCGH Ahmar , Corinne Abdallah MD Active Staff Medicine HCGH Ahmed , Mohammed Shafeeq MD MBA Active Staff Obstetrics and Gynecology HCGH Ahn , Edward Sanghoon MD Courtesy Staff Surgery Neurosurgery HCGH Ahn , Hyo S MD Consulting Staff Diagnostic Imaging HCGH Ahn , Sungkee S MD Active Staff Diagnostic Imaging HCGH Ahuja , Kanwaljit Singh MD Consulting Staff Medicine Neurology HCGH Ahuja , Sarina MD Consulting Staff Medicine HCGH Aina , Abimbola MD Active Staff Obstetrics and Gynecology HCGH Ajayi , Tokunbo Opeyemi MD Active Staff Medicine Internal Medicine HCGH Akenroye , Ayobami Tolulope MBChB MPH Active Staff Medicine Internal Medicine HCGH Akhter , Mahbuba -

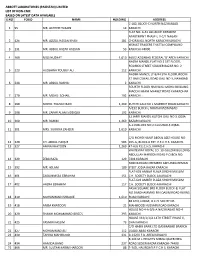

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2021

PERSONS • OF THE YEAR • The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • B The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • i The Muslim 500: The World’s 500 Most Influential Chief Editor: Prof S Abdallah Schleifer Muslims, 2021 Editor: Dr Tarek Elgawhary ISBN: print: 978-9957-635-57-2 Managing Editor: Mr Aftab Ahmed e-book: 978-9957-635-56-5 Editorial Board: Dr Minwer Al-Meheid, Mr Moustafa Jordan National Library Elqabbany, and Ms Zeinab Asfour Deposit No: 2020/10/4503 Researchers: Lamya Al-Khraisha, Moustafa Elqabbany, © 2020 The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre Zeinab Asfour, Noora Chahine, and M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin 20 Sa’ed Bino Road, Dabuq PO BOX 950361 Typeset by: Haji M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin Amman 11195, JORDAN www.rissc.jo All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanic, including photocopying or recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily reflect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Set in Garamond Premiere Pro Printed in The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Calligraphy used throughout the book provided courte- sy of www.FreeIslamicCalligraphy.com Title page Bismilla by Mothana Al-Obaydi MABDA • Contents • INTRODUCTION 1 Persons of the Year - 2021 5 A Selected Surveyof the Muslim World 7 COVID-19 Special Report: Covid-19 Comparing International Policy Effectiveness 25 THE HOUSE OF ISLAM 49 THE -

List of Category -I Members Registered in Membership Drive-Ii

LIST OF CATEGORY -I MEMBERS REGISTERED IN MEMBERSHIP DRIVE-II MEMBERSHIP CGN QUOTA CATEGORY NAME DOB BPS CNIC DESIGNATION PARENT OFFICE DATE MR. DAUD AHMAD OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT COMPANY 36772 AUTONOMOUS I 25-May-15 BUTT 01-Apr-56 20 3520279770503 MANAGER LIMITD MR. MUHAMMAD 38295 AUTONOMOUS I 26-Feb-16 SAGHIR 01-Apr-56 20 6110156993503 MANAGER SOP OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT CO LTD MR. MALIK 30647 AUTONOMOUS I 22-Jan-16 MUHAMMAD RAEES 01-Apr-57 20 3740518930267 DEPUTY CHIEF MANAGER DESTO DY CHEIF ENGINEER CO- PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 7543 AUTONOMOUS I 17-Apr-15 MR. SHAUKAT ALI 01-Apr-57 20 6110119081647 ORDINATOR COMMISSION 37349 AUTONOMOUS I 29-Jan-16 MR. ZAFAR IQBAL 01-Apr-58 20 3520222355873 ADD DIREC GENERAL WAPDA MR. MUHAMMA JAVED PAKISTAN BORDCASTING CORPORATION 88713 AUTONOMOUS I 14-Apr-17 KHAN JADOON 01-Apr-59 20 611011917875 CONTRALLER NCAC ISLAMABAD MR. SAIF UR REHMAN 3032 AUTONOMOUS I 07-Jul-15 KHAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110170172167 DIRECTOR GENRAL OVERS PAKISTAN FOUNDATION MR. MUHAMMAD 83637 AUTONOMOUS I 13-May-16 MASOOD UL HASAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110163877113 CHIEF SCIENTIST PROFESSOR PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISION 60681 AUTONOMOUS I 08-Jun-15 MR. LIAQAT ALI DOLLA 01-Apr-59 20 3520225951143 ADDITIONAL REGISTRAR SECURITY EXCHENGE COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD CHIEF ENGINEER / PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 41706 AUTONOMOUS I 01-Feb-16 LATIF 01-Apr-59 21 6110120193443 DERECTOR TRAINING COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD 43584 AUTONOMOUS I 16-Jun-15 JAVED 01-Apr-59 20 3820112585605 DEPUTY CHIEF ENGINEER PAEC WASO MR. SAGHIR UL 36453 AUTONOMOUS I 23-May-15 HASSAN KHAN 01-Apr-59 21 3520227479165 SENOR GENERAL MANAGER M/O PETROLEUM ISLAMABAD MR. -

Pld 2017 Sc 70)

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (Original Jurisdiction) PRESENT: Mr. Justice Asif Saeed Khan Khosa Mr. Justice Ejaz Afzal Khan Mr. Justice Gulzar Ahmed Mr. Justice Sh. Azmat Saeed Mr. Justice Ijaz ul Ahsan Constitution Petition No. 29 of 2016 (Panama Papers Scandal) Imran Ahmad Khan Niazi Petitioner versus Mian Muhammad Nawaz Sharif, Prime Minister of Pakistan / Member National Assembly, Prime Minister’s House, Islamabad and nine others Respondents For the petitioner: Syed Naeem Bokhari, ASC Mr. Sikandar Bashir Mohmad, ASC Mr. Fawad Hussain Ch., ASC Mr. Faisal Fareed Hussain, ASC Ch. Akhtar Ali, AOR with the petitioner in person Assisted by: Mr. Yousaf Anjum, Advocate Mr. Kashif Siddiqui, Advocate Mr. Imad Khan, Advocate Mr. Akbar Hussain, Advocate Barrister Maleeka Bokhari, Advocate Ms. Iman Shahid, Advocate, For respondent No. 1: Mr. Makhdoom Ali Khan, Sr. ASC Mr. Khurram M. Hashmi, ASC Mr. Feisal Naqvi, ASC Assisted by: Mr. Saad Hashmi, Advocate Mr. Sarmad Hani, Advocate Mr. Mustafa Mirza, Advocate For the National Mr. Qamar Zaman Chaudhry, Accountability Bureau Chairman, National Accountability (respondent No. 2): Bureau in person Mr. Waqas Qadeer Dar, Prosecutor- Constitution Petition No. 29 of 2016, 2 Constitution Petition No. 30 of 2016 & Constitution Petition No. 03 of 2017 General Accountability Mr. Arshad Qayyum, Special Prosecutor Accountability Syed Ali Imran, Special Prosecutor Accountability Mr. Farid-ul-Hasan Ch., Special Prosecutor Accountability For the Federation of Mr. Ashtar Ausaf Ali, Attorney-General Pakistan for Pakistan (respondents No. 3 & Mr. Nayyar Abbas Rizvi, Additional 4): Attorney-General for Pakistan Mr. Gulfam Hameed, Deputy Solicitor, Ministry of Law & Justice Assisted by: Barrister Asad Rahim Khan Mr. -

Arabic Books Published in India an Annotated Bibliography

ARABIC BOOKS PUBLISHED IN INDIA AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBRARY SCIENCE 1986-86 BY ISHTIYAQUE AHMAD Roll No, 85-M. Lib. Sc.-02 Enrolment No. S-2247 Under the Supervision of Mr. AL-MUZAFFAR KHAN READER DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 1986 ,. J^a-175 DS975 SJO- my. SUvienJU ACKNOWLEDGEMENT It is not possible for me to thank adequately prof, M.H. Rizvi/ University Librarian and Chairman Department of Library Science. His patronage indeed had always been a source of inspiration, I stand deeply indebted to my supervisor, Mr. Al- Muzaffar Khan, Reader, Department of Library Science without whom invaluable suggestions and worthy advice, I would have never been able to complete the work. Throughout my stay in the department he obliged me by unsparing help and encouragement. I shall be failing in my daties if I do not record the names of Dr. Hamid All Khan, Reader, Department of Arabic and Mr, Z.H. Zuberi, P.A., Library of Engg. College with gratitude for their co-operation and guidance at the moment I needed most, I must also thank my friends M/s Ziaullah Siddiqui and Faizan Ahmad, Research Scholars, Arabic Deptt., who boosted up my morals in the course of wtiting this dis sertation. My sincere thanks are also due to S. Viqar Husain who typed this manuscript. ALIGARH ISHl'ltAQUISHTIYAQUE AAHMA D METHODOLOBY The present work is placed in the form of annotation, the significant Arabic literature published in India, The annotation of 251 books have been presented. -

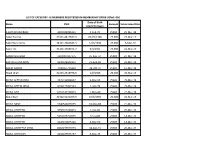

Name CNIC Date of Birth (Dd/Mm/Yyyy) Amount Submission

LIST OF CATEGORY -III MEMBERS REGISTERED IN MEMBERSHIP DRIVE-II(Part-4th) Date of Birth Name CNIC Amount Submission Date (dd/mm/yyyy) A SATTAR UMERANI 4200036095311 1-Feb-70 25000 25-Mar-19 Aaber Farooq 33301-4817637-3 03/09/1986 25,000 25-Mar-19 Aabis Raza Kazmi 34101-7982643-3 14/9/1990 25,000 6-Mar-19 Aamir Ali 31101-3366151-7 9/9/1991 25,000 21-Mar-19 AAMIR SHAHZAD 3310007107175 25-Sep-72 25000 21-Mar-19 AASHIQ ALI MEMON 4330329942951 21-Aug-69 25000 22-Mar-19 AASIM BASHIR 3740567745419 20-Oct-70 25000 11-Mar-19 Abaid Ullah 32103-2518976-5 1/6/1966 25,000 25-Mar-19 ABDUL ALEEM KHAN 3520230658047 9-Mar-65 25000 25-Mar-19 ABDUL AZEEM JATOI 4230177451543 1-Apr-78 25000 25-Mar-19 ABDUL AZIZ 6110142134913 1-May-64 25000 22-Mar-19 Abdul Bari 32402-5221299-9 10/9/1965 25,000 25-Mar-19 ABDUL BASIT 3740540476955 24-Mar-88 25000 21-Mar-19 ABDUL GHAFFAR 3550102289413 1-Apr-89 25000 25-Mar-19 ABDUL GHAFFAR 5210105714535 17-Jul-80 25000 14-Mar-19 ABDUL GHAFFAR 4220102855149 4-Mar-60 25000 14-Mar-19 ABDUL GHAFFFAR KHAN 8210299699793 18-Dec-71 25000 25-Mar-19 ABDUL GHAFOOR 4230109573757 6-Mar-75 25000 25-Mar-19 Date of Birth Name CNIC Amount Submission Date (dd/mm/yyyy) ABDUL GHAFOOR 3740615687037 22-Oct-63 25000 22-Mar-19 ABDUL GHAFOOR SANJRANI 4230103641849 30-May-57 25000 18-Mar-19 ABDUL HAFEEZ 4130381796287 2-Mar-85 25000 18-Mar-19 Abdul Hameed 35202-5798517-7 13/11/1951 25,000 13-Mar-19 ABDUL HAMEED 4240116994783 20-Sep-62 25000 25-Mar-19 ABDUL HAMID 4210178803863 12-Mar-63 25000 22-Mar-19 ABDUL HAMID KHAN 4210115977797 12-Jan-64 25000 25-Mar-19 -

Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, As Amended

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/17/2013 12:53:25 PM OMB NO. 1124-0002; Expires February 28, 2014 «JJ.S. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended For Six Month Period Ending 06/30/2013 (Insert date) I - REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Pakistan Tehreek e Insaf 5975 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 315 Maple street Richardson TX, 75081 Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) Yes Q No D (2) Citizenship Yes Q No Q (3) Occupation Yes • No D (b) If an organization: (1) Name Yes Q No H (2) Ownership or control Yes • No |x] - (3) Branch offices Yes D No 0 (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3,4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes D No H If yes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes • No D If no, please attach the required amendment. I The Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists of a true copy of the charter, articles of incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an organization. (A waiver of the requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

University of Peshawar (Master Admission Test) UAT-BIOS(Evening)

University Of Peshawar (Master Admission Test) Test held on 21st October,2017 UAT-BIOS(Evening) Sr# RollNo NTSFormNo Admission_Form_No Name FatherName NTSMarks 1 951277 40052 1020 TALHA RAHIM FAZAL RAHIM 63 2 951167 40604 626 SYED GHAYAS ALI SHAH SYED MIR KARIM SHAH 63 3 951829 40758 523 MAHNOOR KHATTAK ASIF KHATTAK 61 4 951948 40764 3142 ABIDA ABDUL HALEEM 60 5 951391 40770 1411 HAIDER ALI AFRIDI KHAN ZALI 60 6 951294 40304 1105 MASAUD KHAN SHAHWAWLI 60 7 952132 40680 397 RIZWAN ULLAH NASRULLAH KHAN 59 8 952019 40935 3495 LAIBA SHAH TAJAMMUL SHAH 59 9 952157 40944 3893 ATIQ AHMAD SHAH ZAMIN MIAN 59 10 951153 40981 1280 HIRA SHAH LUQMAN SHAH 59 11 951227 41080 851 FOZIA TAIEB MOHAMMAD TAIEB 58 12 951621 40774 2223 MUHAMMAD ADNAN MUHAMMAD RAMZAN 58 13 951072 40320 205 ZUBAIR AHMAD NUSRAT KHAN 58 14 951402 40116 1257 SOFIA IHSAN UL HAQ 58 15 951417 40194 1521 MUHAMMAD ABDUL WAHAB INAYAT ULLAH 58 16 951058 40317 208 WASEEM AKRAM SHAMSHAD GUL 57 17 951747 40473 2572 ABRAR HUSSAIN BAIDAR KHAN 57 18 951132 40532 517 HARIS GHANI IFTIKHAR GHANI KHAN 57 19 951727 40833 2920 LAIBA MUSHTAQ MUSHTAQ MUHAMMAD 57 20 951808 40672 2737 ZUBAIR AHMAD YAQOOT SHAH 56 21 951074 40610 294 RAHMAN ULLAH KHAN ADAM KHAN 56 22 951901 41047 3028 IRFAN ULLAH NOOR ZADIN 56 23 951703 40480 2491 PIYAZUR RAHMAN SULTAN HAMEED 56 24 951110 40344 426 MUHAMMAD NAEEM KHAN FAZAL RAHIM KHAN 56 25 951796 40407 2689 MUHAMMAD ABBAS MIAN GUL HUSSAIN 56 26 951527 40208 1946 MARWA MAJEED FAZAL MAJEED 56 27 951098 40073 380 AMIR IQBAL IQBAL HUSSAIN 56 28 951656 40204 2359 MUHAMMAD -

Hackney Carriage/Private Hire Drivers

STOCKTON-ON-TEES BOROUGH COUNCIL - REGISTER OF LICENSED HACKNEY CARRIAGE/PRIVATE HIRE DRIVERS THIS REGISTER WILL BE UPDATED EVERY 12 WEEKS (LAST UPDATE: 14/06/21) TYPE OF LICENCE LICENCE NAME START DATE EXPIRY DATE NUMBER Private Hire Driver DRV 002 Mr Kashaf Moghal 01/05/2021 30/04/2022 Hackney Carriage Driver DRV 003 Mr Tariq Ali 01/05/2021 30/04/2022 Combined Driver DRV 005 Mr James Currie 01/04/2021 31/03/2022 Combined Driver DRV 007 Mr Mohammed Rhaoof Fazal 16/12/2020 30/04/2022 Private Hire Driver DRV 029 Mr Naveed Hussain 01/02/2020 31/01/2023 Hackney Carriage Driver DRV 030 Mr John Robert Fielding 01/04/2021 31/03/2022 Private Hire Driver DRV 033 Mr Mohammed Ali Saddique 01/03/2020 28/02/2023 Combined Driver DRV 037 Mr Tahir Ali 01/03/2020 28/02/2023 Private Hire Driver DRV 038 Mr Mohammed Razaq 01/10/2018 30/09/2021 Combined Driver DRV 041 Mr Saeed Bashir 01/12/2018 30/11/2021 Combined Driver DRV 044 Mr Lee Edwin Strange 01/06/2021 31/05/2022 Combined Driver DRV 049 Mr Zulfiqar Ali 01/12/2020 30/11/2023 Hackney Carriage Driver DRV 052 Mr Sabir Hussain 01/12/2020 30/11/2021 Combined Driver DRV 056 Mr Liaquat Ali 01/05/2019 30/04/2022 Combined Driver DRV 062 Mr Mohammed Ilyas 01/06/2019 31/05/2022 Combined Driver DRV 067 Mr Agha Abdul Salam Khan 01/03/2021 28/02/2022 Hackney Carriage Driver DRV 068 Mr Gordon Cutler 01/09/2020 31/08/2021 Hackney Carriage Driver DRV 069 Mr Anthony Keith Lea 01/03/2020 28/02/2023 Combined Driver DRV 071 Mr Anthony Michael Leeming 01/07/2021 30/06/2022 Combined Driver DRV 075 Mr Asif Mahmood 01/01/2020