Undermining Safety: a Report on Coal Mine Safety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Real Effects of Mandatory Dissemination of Non- Financial Information Through Financial Reports

Working Paper No. 16-04 The Real Effects of Mandatory Dissemination of Non- Financial Information through Financial Reports Hans B. Christensen University of Chicago Booth School of Business Eric Floyd Rice University Jones School of Business Lisa Yao Liu University of Chicago Booth School of Business Mark Maffett University of Chicago Booth School of Business All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs. May be quoted without Explicit permission, provided that full credit including notice is given to the source. This paper also can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection. The Real Effects of Mandatory Dissemination of Non-Financial Information through Financial Reports By HANS B. CHRISTENSEN, ERIC FLOYD, LISA YAO LIU and MARK MAFFETT* February 2016 Abstract: We examine the real effects of mandatory, non-financial disclosures, which require SEC-registered mine owners to disseminate their mine-safety records through their financial reports. These safety records are already publicly available elsewhere, which allows us to examine the incremental effects of disseminating information through financial reports. Comparing mines owned by SEC-registered issuers to those mines that are not, we document that including safety records in financial reports decreases mining-related citations and injuries by 11 and 13 percent, respectively, and reduces labor productivity by approximately 0.9 percent. Additional evidence suggests that increased dissemination, rather than unobservable factors associated with regulatory intervention, drive these effects. We also provide evidence that feedback effects from equity markets are a potential mechanism through which the dissemination of information leads to real effects. -

Approaching Coal Mine Safety from a Comparative Law and Interdisciplinary Perspective

Volume 111 Issue 1 Article 5 September 2008 Approaching Coal Mine Safety from a Comparative Law and Interdisciplinary Perspective Anne Marie Lofaso West Virginia University College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons, Mining Engineering Commons, and the Oil, Gas, and Mineral Law Commons Recommended Citation Anne M. Lofaso, Approaching Coal Mine Safety from a Comparative Law and Interdisciplinary Perspective, 111 W. Va. L. Rev. (2008). Available at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr/vol111/iss1/5 This Thinking Outside the Box: A Post-Sago Look at Coal Mine Safety is brought to you for free and open access by the WVU College of Law at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Virginia Law Review by an authorized editor of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lofaso: Approaching Coal Mine Safety from a Comparative Law and Interdisc APPROACIIING COAL MINE SAFETY FROM A COMPARATIVE LAW AND INTERDISCIPLINARY PERSPECTIVE Anne Marie Lofaso* I. IN TROD UCTION ....................................................................................... I II. COAL MINE SAFETY CONCERNS ......................................................... 2 A. Overview of U.S. Coal Mine Industry's Safety Issues............. 2 B. Case Study: Sago ................................................................. 3 C. Questions Raised in Sago 's Aftermath .................................. -

It's About Time: a Proposal to Establish A

NOTES IT’S ABOUT TIME: A PROPOSAL TO ESTABLISH A SPECIALIZED INTERNATIONAL AGENCY FOR COAL MINER SAFETY AND HEALTH Mining is inherently high risk and will always remain so as long as it is done by people. All underground mines face the same problems. It takes eternal vigilance to stay on top of it.1 I. INTRODUCTION Traditionally, underground coal mining has posed significant risks to workers’ health and safety.2 Through continued improvements in technologies, new capital investments, and continuously improved training, some dangers have been controlled.3 However, without a “safety net” including assessments and control of risks, “accidents and occupational diseases can and do occur.”4 Looking back at the recent coal mining disasters across the world, it is clear that uniform global safety and health standards for coal mining are imperative. Even though coal mining claims the lives of thousands of human beings across the world each year, it is a fundamental energy source that cannot be abandoned in the foreseeable future.5 The global 1. Charles Hutzler, World’s Coal Use Carries Deadly Cost, ASSOCIATED PRESS, Nov. 11, 2007 (quoting Dave Feickert, an independent mine safety consultant based in New Zealand, who has worked extensively in China). 2. International Labour Organization, Sector Meetings: Meeting of Experts on Safety and Health of Coal Mines, May 8-13, 2006, http://www.ilo.org/public/english/dialogue/sector/techmeet/meshcm06/index.htm. 3. Id. 4. Id. 5. In 2006, there were seventy-three total mining deaths in the United States, forty-seven of which were related to coal mining. -

Twists and Turns in Ancient Roads: As Unidentified

CLIMATE CHANGE AND THE WAR ON COAL: EXPLORING THE DARK SIDE Patrick Charles McGinley∗ To see coal purely as a gift from God overlooks the many dangerous strings attached to that gift. Similarly, to see it as just an environmental evil would be to overlook the undeniable good that accompanies that evil. “Failing to recognize both sides of coal—the vast power and the exorbitant costs—misses the essential, heartbreaking drama of the story.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................... 256 I. Coal at the Millennium .......................................................................... 258 II. History of Coal ..................................................................................... 262 A. Early History .................................................................................... 262 B. Coal and the Industrial Age .............................................................. 262 C. Coal and Industrialization in the United States ................................ 263 III. Coal’s Dark Side: Examining its Externalities .................................... 265 A. The Socio-Economic Costs of Coal Mining and Burning ................ 266 1. Industrial Awakening in the Coalfields .............................. 266 ∗ Professor McGinley is the “Judge Charles H. Haden II Professor of Law” at West Virginia University. In the print version of Volume 13 Issue 2, the Vermont Journal of Environmental Law mistakenly inserted the name of a purported "co-author." -

Robert C. Byrd Miner Safety and Health Act of 2010

111TH CONGRESS REPT. 111–579 " ! 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Part 1 ROBERT C. BYRD MINER SAFETY AND HEALTH ACT OF 2010 JULY 29, 2010.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. GEORGE MILLER of California, from the Committee on Education and Labor, submitted the following R E P O R T together with SUPPLEMENTAL AND MINORITY VIEWS [To accompany H.R. 5663] [Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] The Committee on Education and Labor, to whom was referred the bill (H.R. 5663) to improve compliance with mine and occupa- tional safety and health laws, empower workers to raise safety con- cerns, prevent future mine and other workplace tragedies, establish rights of families of victims of workplace accidents, and for other purposes, having considered the same, report favorably thereon with an amendment and recommend that the bill as amended do pass. The amendment is as follows: Strike all after the enacting clause and insert the following: SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. (a) SHORT TITLE.—This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Robert C. Byrd Miner Safety and Health Act of 2010’’. (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents for this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title; table of contents. Sec. 2. References. TITLE I—ADDITIONAL INSPECTION AND INVESTIGATION AUTHORITY Sec. 101. Independent accident investigations. Sec. 102. Subpoena authority and miner rights during inspections and investigations. Sec. 103. Designation of miner representative. Sec. 104. Additional amendments relating to inspections and investigations. -

Beyond Greed and Fear Financial Management Association Survey and Synthesis Series

Beyond Greed and Fear Financial Management Association Survey and Synthesis Series The Search for Value: Measuring the Company's Cost of Capital Michael C. Ehrhardt Managing Pension Plans: A Comprehensive Guide to Improving Plan Performance Dennis E. Logue and Jack S. Rader Efficient Asset Management: A Practical Guide to Stock Portfolio Optimization and Asset Allocation Richard O. Michaud Real Options: Managing Strategic Investment in an Uncertain World Martha Amram and Nalin Kulatilaka Beyond Greed and Fear: Understanding Behavioral Finance and the Psychology of Investing Hersh Shefrin Dividend Policy: Its Impact on Form Value Ronald C. Lease, Kose John, Avner Kalay, Uri Loewenstein, and Oded H. Sarig Value Based Management: The Corporate Response to Shareholder Revolution John D. Martin and J. William Petty Debt Management: A Practitioner's Guide John D. Finnerty and Douglas R. Emery Real Estate Investment Trusts: Structure, Performance, and Investment Opportunities Su Han Chan, John Erickson, and Ko Wang Trading and Exchanges: Market Microstructure for Practitioners Larry Harris Beyond Greed and Fear Understanding Behavioral Finance and the Psychology of Investing Hersh Shefrin 2002 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Copyright © 2002 by Oxford University Press, Inc. -

Evaluating the Effectiveness of MSHA's Mine Safety and Health

EVALUATING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF MSHA’S MINE SAFETY AND HEALTH PROGRAMS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND LABOR U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION HEARING HELD IN WASHINGTON, DC, MAY 16, 2007 Serial No. 110–38 Printed for the use of the Committee on Education and Labor ( Available on the Internet: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/house/education/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 35–186 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 16:58 Mar 13, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 G:\DOCS\110TH\FC\110-38\35186.TXT HBUD1 PsN: DICK COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND LABOR GEORGE MILLER, California, Chairman Dale E. Kildee, Michigan, Vice Chairman Howard P. ‘‘Buck’’ McKeon, California, Donald M. Payne, New Jersey Ranking Minority Member Robert E. Andrews, New Jersey Thomas E. Petri, Wisconsin Robert C. ‘‘Bobby’’ Scott, Virginia Peter Hoekstra, Michigan Lynn C. Woolsey, California Michael N. Castle, Delaware Rube´n Hinojosa, Texas Mark E. Souder, Indiana Carolyn McCarthy, New York Vernon J. Ehlers, Michigan John F. Tierney, Massachusetts Judy Biggert, Illinois Dennis J. Kucinich, Ohio Todd Russell Platts, Pennsylvania David Wu, Oregon Ric Keller, Florida Rush D. Holt, New Jersey Joe Wilson, South Carolina Susan A. Davis, California John Kline, Minnesota Danny K. Davis, Illinois Cathy McMorris Rodgers, Washington Rau´ l M. -

59Th Annual Distinguished Service Award Harvey P. Eisen, BS BA

59th Annual Distinguished Service Award Harvey P. Eisen, BS BA '64 Chairman, CEO and Director, Wright Investors' Service Holdings, Inc. Chairman and Managing Partner; Bedford Oak Advisers, LLC Chairman and Director, GP Strategies Harvey P. Eisen is Chairman, CEO and Director of Wright Investors’ Service Holdings, Inc. (WISH), formerly National Patent Development Corporation. He has also served as Chairman of Bedford Oak Advisors, LLC, an investment partnership since 1998, and Chairman and Director of GP Strategies since 2004. He was previously Senior Vice President of Travelers, Inc. and held various executive positions with Primerica, SunAmerica Corp., and Integrated Resources Asset Management. Mr. Eisen was president and portfolio manager of Eisen Capital Management for 10 years. He began his career as an analyst with Stifel, Nicolaus & Co. and Wertheim. Mr. Eisen has served on the Strategic Development Board for the Trulaske College of Business, University of Missouri since 1995 where he established the first accredited course on the Warren Buffett Principles of Investing. He also serves on the Zanvyl Krieger School of Arts and Sciences Advisory Board for Johns Hopkins University and is a member of the Carey Business School Board of Overseers and the Hopkins Parents Council. Mr. Eisen is widely recognized as one of the country’s leading portfolio managers. With over three decades of investment experience, he is often consulted by the national media for his expert views on all phases of the investment marketplace and is frequently quoted in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Pension World, U.S. News & World Report, Financial World and Business Week, among others. -

Independent Report on Sago

The Sago Mine Disaster A preliminary report to Governor Joe Manchin III J. Davitt McAteer and associates July • 2006 The Sago Mine Disaster A preliminary report to Governor Joe Manchin III J. Davitt McAteer and associates: Thomas N. Bethell Celeste Monforton Joseph W. Pavlovich Deborah Roberts Beth Spence JULY • 2006 Buckhannon, West Virginia On January 12, 2006, West Virginia Senate President Earl Ray Tomblin (D-Chapmanville) and House Speaker Bob Kiss (D-Raleigh) appointed Senators Don Caruth (R-Mercer), Jeff Kessler (D-Marshall) and Shirley Love (D-Fayette) and Delegates Mike Caputo (D-Marion), Eustace Frederick (D-Mercer) and Bill Hamilton (R-Upshur) to conduct an inquiry into the Sago disaster. At the request of Governor Joe Manchin III, their inquiry was conducted jointly with our investigation. These legislators have worked diligently with us in seeking answers to this West Virginia tragedy. This report, as well as additional related information, is available at: www.wvgov.org and www.wju.edu Front cover photo: Memorial ribbons on the Sago Mine security fence, January 2006 Jeff Swensen / Getty Images Back cover photo: Mourners praying at the funeral of Jerry Groves, January 2006 Haraz Ghanbari / AP Images Contents Letter of transmittal ..........................................................2 Dedication........................................................................4 1. Executive Summary .......................................................7 2. Recommendations ...................................................... -

Coal Mine Safety and Health

Order Code RL34429 Coal Mine Safety and Health March 31, 2008 Linda Levine Specialist in Labor Economics Domestic Social Policy Division Coal Mine Safety and Health Summary Safety in the coal mining industry is much improved compared to the early decades of the twentieth century, a time when hundreds of miners could lose their lives in a single accident and more than 1,000 fatalities could occur in a single year. Fatal injuries associated with coal mine accidents fell almost continually between 1925 and 2005, when they reached an all-time low of 23. As a result of 12 deaths at West Virginia’s Sago mine and fatalities at other coal mines in 2006, however, the number of fatalities more than doubled to 47. Fatalities declined a year later to 33, which is comparable to levels achieved during the late 1990s. In addition to the well above-average fatal injury rates they face, coal miners suffer from occupationally caused diseases. Prime among them is black lung (coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, CWP), which still claims about 1,000 fatalities annually. Although improved dust control requirements have led to a decrease in the prevalence of CWP, there is recent evidence of advanced cases among miners who began their careers after the stronger standards went into effect in the early 1970s. In addition, disagreement persists over the current respirable dust limits and the degree of compliance with them by mine operators. In the wake of the January 2006 Sago mine accident, the U.S. Department of Labor’s Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) was criticized for its slow pace of rulemaking earlier in the decade. -

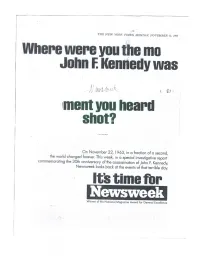

Its Time For

THE NEW YORK TIMES, MONDAY, NOVEMBER 15, 1993 Where were you the mo John F. Kennedy was tur1/1!:-i z Iment you heard shot? b011,3,111. On November 22, 1963, in a fraction of a second, the world changed forever. This week, in a special investigative report commemorating the 30th anniversary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Newsweek looks back at the events of that terrible day. Its time for Newsweek. Winner of the National Magazine Award for General Excellence Newsweek Ir HO' 71:171 "_, .‘" It's Nut Whet YOu Think was in my third year of college, and I was walking with my friend, Alan Placa, now Monsignor Placa. Someone came up to us and said that President Kennedy had been shot. At first, we thought it was a joke or a wild report. Then, some- one else said it to us. We went to a radio nearby where we heard the news report. Then we went to I remember the day well. I was at my car and put on the radio We the office when I heard. I ran out sat in the car for over one hour just of my office into the hall - I wanted listening in shock because we io call out the news to everyone. I didn't wont to leave until they started to cry; I couldn't get the announced it, that he was actually words out, Everyone stayed con- dead " gregated in the halls for some Rudolph Giuliani time. We all wanted to be together Mayor Elect, City of New York with each other in our sorrow.' Ed Meyer Chairman/President and Chief Executive Officer Grey Advertising was leaving the Beverly Hills Post Office. -

SAGO MINE EXPLOSION Which Occurred JANUARY 2, 2006

REPORT of INVESTIGATION into the SAGO MINE EXPLOSION which occurred JANUARY 2, 2006 UPSHUR CO. WEST VIRGINIA WEST VIRGINIA OFFICE of MINERS’ HEALTH, SAFETY, AND TRAINING DECEMBER 11, 2006 RON WOOTEN, DIRECTOR CONTENTS Letter of Transmittal The Board of Coal Mine Health and Safety Definitions Errata 1 Executive Summary 2 Foreword 3 Mine Rescue 4 The Mine Recovery 5 The Investigation 6 Recommendations 7 List of Appendices DEFINITIONS WV Office of Miners’ Health Safety and Training: Various abbreviations used in this report include WVOMHS&T, WVMHS&T of OMHS&T NIOSH: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Portal: Mine entrance (a.k.a. “drift” or “drift mouth”) Mains: Major travel-way of a mine. Starting at the portal and usually continuing to the farthest extend of the mine. Section: Work area of a mine. The location where coal is actively extracted for the mine. Face: Farthest extent of the mining section. Area where the coal is actually extracted. Mouth: Beginning of the section. Area where section branches from the mains. Inby: Direction or location from your present location and progressing in an inward direction of the mine (looking / moving from the outside - in). Outby: Direction or location from your present location and progressing in an outward direction of the mine (looking / moving from the inside – out). First mining: The initial development of a section. Mining in an area where the mine has not been developed. (a.k.a. “advance mining”). Second mining: Additional mining of support pillars or sometimes a lower coal seam that commences, after first mining is completed, as the sections withdraws outby (a.k.a.