The Current Status of Religious Coexistence and Education in Bosnia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In a Divided Bosnia, Segregated Schools Persist

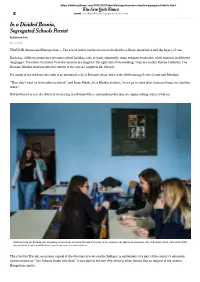

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/01/world/europe/bosnia-schools-segregated-ethnic.html EUROPE | In a Divided Bosnia, Segregated Schools Persist In a Divided Bosnia, Segregated Schools Persist By Barbara Surk Dec. 1, 2018 TRAVNIK, Bosnia and Herzegovina — The school in this medieval town is divided by a flimsy metal fence and the legacy of war. Each day, children stream into the same school building, only to study separately, using separate textbooks, while learning in different languages. The ethnic Croatians from the suburbs are taught in the right side of the building. They are mostly Roman Catholics. The Bosnian Muslim students who live mostly in the city are taught in the left side. For many of the students, the split is an unwanted relic of Bosnia’s ethnic wars of the 1990s among Serbs, Croats and Muslims. “They don’t want us to socialize in school,” said Iman Maslic, 18, a Muslim student, ”so we go to cafes after class and hang out together there.” But unwanted or not, the divide is deepening in a Bosnia where nationalist politicians are again stoking ethnic rivalries. Students from the Bosniak side attending a class in the school in Travnik. For many of the students, the split is an unwanted relic of Bosnia’s ethnic wars of the 1990s among Serbs, Croats and Muslims. Laura Boushnak for The New York Times The school in Travnik, an ancient capital of the Ottoman province in the Balkans, is emblematic of a part of the country’s education system known as “Two Schools Under One Roof.” It was built in the late 19th century, when Bosnia was an outpost of the Austro‑ Hungarian empire. -

The War in Bosnia and Herzegovina Or the Unacceptable Lightness of “Historicism”

The War in Bosnia and Herzegovina Or the Unacceptable Lightness of “Historicism” Davor Marijan War Museum, Zagreb, Republic of Croatia Abstract The author in this study does not intend to provide a comprehensive account of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, in part because the cur- rent level of research does not enable this. The only way to understand this conflict is through facts, not prejudices. However, such prejudices are particularly acute amongst Muslim-Bosniac authors. They base their claims on the notion that Serbs and Croats are the destroyers of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and that both are equally culpable in its destruction. Relying on mainly unpublished and uncited documents from the three constitutive nations of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the author factually chal- lenges basic and generally accepted claims. The author offers alternative responses to certain claims and draws attention to the complexity of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which has been mainly viewed in terms of black or white. The author does, however, suggest that in considering the character of the war it is necessary to examine first the war in Croatia and the inter-relationship between the two. The main focus is on 1992 and the Muslim and Croat differences that developed into open conflict at the beginning of 1993. The role of the international community in the war and the partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina are also discussed. At the end of the 20th century in Europe and the eclipse of Communism from the world political scene, it is not easy to trace the indelible marks left behind after the collapse of Yugoslavia and the wars that ensued. -

Bosnia and Herzegovina Joint Opinion on the Legal

Strasbourg, Warsaw, 9 December 2019 CDL-AD(2019)026 Opinion No. 951/2019 Or. Engl. ODIHR Opinion Nr.:FoA-BiH/360/2019 EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) OSCE OFFICE FOR DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS AND HUMAN RIGHTS (OSCE/ODIHR) BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA JOINT OPINION ON THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK GOVERNING THE FREEDOM OF PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, IN ITS TWO ENTITIES AND IN BRČKO DISTRICT Adopted by the Venice Commission at its 121st Plenary Session (Venice, 6-7 December 2019) On the basis of comments by Ms Claire BAZY-MALAURIE (Member, France) Mr Paolo CAROZZA (Member, United States of America) Mr Nicolae ESANU (Substitute member, Moldova) Mr Jean-Claude SCHOLSEM (substitute member, Belgium) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-AD(2019)026 - 2 - Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 3 II. Background and Scope of the Opinion ...................................................................... 4 III. International Standards .............................................................................................. 5 IV. Legal context and legislative competence .................................................................. 6 V. Analysis ..................................................................................................................... 8 A. Definitions of public assembly .................................................................................. -

Bosnia and Herzegovina Page 1 of 7

Bosnia and Herzegovina Page 1 of 7 Bosnia and Herzegovina International Religious Freedom Report 2008 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor The Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) and the entity Constitutions of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (the Federation) and the Republika Srpska (RS) provide for freedom of religion; the Law on Religious Freedom also provides comprehensive rights to religious communities. These and other laws and policies contributed to the generally free practice of religion. The Government generally respected religious freedom in practice. Government protection of religious freedom improved slightly during the period covered by this report; however, local authorities continued at times to restrict religious freedom of minority religious groups. Societal abuses and discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice persisted. Discrimination against religious minorities occurred in nearly all parts of the country. The number of incidents targeting religious symbols, clerics, and property in the three ethnic majority areas decreased. Local religious leaders and politicians contributed to intolerance and an increase in nationalism through public statements. Religious symbols were often misused for political purposes. A number of illegally constructed religious objects continued to cause tension and conflict in various communities. The U.S. Government discusses religious freedom with the Government and leaders from the four traditional religious communities and emerging religious groups as part of its overall policy to promote human rights and reconciliation. The U.S. Embassy supported religious communities in their efforts to acquire permits to build new religious structures. The Embassy also assisted religious communities regarding restitution of property and supported several exchange, speaking, and cultural programs promoting religious freedom. -

Worlds Apart: Bosnian Lessons for Global Security

Worlds Apart Swanee Hunt Worlds Apart Bosnian Lessons for GLoBaL security Duke university Press Durham anD LonDon 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. To my partners c harLes ansBacher: “Of course you can.” and VaLerie GiLLen: “Of course we can.” and Mirsad JaceVic: “Of course you must.” Contents Author’s Note xi Map of Yugoslavia xii Prologue xiii Acknowledgments xix Context xxi Part i: War Section 1: Officialdom 3 1. insiDe: “Esteemed Mr. Carrington” 3 2. outsiDe: A Convenient Euphemism 4 3. insiDe: Angels and Animals 8 4. outsiDe: Carter and Conscience 10 5. insiDe: “If I Left, Everyone Would Flee” 12 6. outsiDe: None of Our Business 15 7. insiDe: Silajdžić 17 8. outsiDe: Unintended Consequences 18 9. insiDe: The Bread Factory 19 10. outsiDe: Elegant Tables 21 Section 2: Victims or Agents? 24 11. insiDe: The Unspeakable 24 12. outsiDe: The Politics of Rape 26 13. insiDe: An Unlikely Soldier 28 14. outsiDe: Happy Fourth of July 30 15. insiDe: Women on the Side 33 16. outsiDe: Contact Sport 35 Section 3: Deadly Stereotypes 37 17. insiDe: An Artificial War 37 18. outsiDe: Clashes 38 19. insiDe: Crossing the Fault Line 39 20. outsiDe: “The Truth about Goražde” 41 21. insiDe: Loyal 43 22. outsiDe: Pentagon Sympathies 46 23. insiDe: Family Friends 48 24. outsiDe: Extremists 50 Section 4: Fissures and Connections 55 25. -

Letter from Bosnia and Herzegovina

184 THE NATIONAL MEDICAL JOURNAL OF INDIA VOL. 12, NO.4, 1999 Letter from Bosnia and Herzegovina HEALTH CARE AND THE WAR Before the war The war in Bosnia and Herzegovina started in November 1991 Until 1991, under the communist regime, the health care system with Serb attacks on the Croatian village of Ravno in south-east- of Bosnia and Herzegovina was centrally based, led and finan- ern Herzegovina and lasted until the Dayton Peace Agreement in ced, and was ineffective relative to comprehensive availability of 1 November 1995. The United Nations Security Council wrote 51 health personnel. 5,6 All resources (personnel, premises and tech- resolutions, one of which declared Serbia and Montenegro as nological equipment) were mainly in urban centres, with only a aggressors to the rest of the Yugoslavian Federation.' The country few situated in the remote rural areas, The health care system had suffered heavy damages, including that to the health care facilities three levels: primary, secondary, and tertiary care. 6 The total num- (hospitals, health centres, and pharmacies). 3 The damage to health ber of highly educated personnel-physicians and pharmacists care facilities is estimated to be US$ 13.85 million.' The Dayton with their associated specialties (1701 )-was high. In 1991, there Peace Agreement virtually preserved Bosnia and Herzegovina as were 23 medical personnel teams per 10000 inhabitants. 6 In 1991, an intact, internationally recognized state. However, it became there was recession with enormous inflation, which resulted in the divided into two entities-the Republic of Srpska, mainly popu- breakdown of the health care system and cessation of functioning lated by Serbs, and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina of financial institutions. -

Nijaz Ibrulj Faculty of Philosophy University of Sarajevo BOSNIA PORPHYRIANA an OUTLINE of the DEVELOPMENT of LOGIC in BOSNIA AN

UDK 16 (497.6) Nijaz Ibrulj Faculty of philosophy University of Sarajevo BOSNIA PORPHYRIANA AN OUTLINE OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF LOGIC IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Abstract The text is a drought outlining the development of logic in Bosnia and Herzegovina through several periods of history: period of Ottoman occupation and administration of the Empire, period of Austro-Hungarian occupation and administration of the Monarchy, period of Communist regime and administration of the Socialist Republic and period from the aftermath of the aggression against the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina to this day (the Dayton Bosnia and Herzegovina) and administration of the International Community. For each of the aforementioned periods, the text treats the organization of education, the educational paradigm of the model, status of logic as a subject in the educational system of a period, as well as the central figures dealing with the issue of logic (as researchers, lecturers, authors) and the key works written in each of the periods, outlining their main ideas. The work of a Neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry, “Introduction” (Greek: Eijsagwgh;v Latin: Isagoge; Arabic: Īsāġūğī) , can be seen, in all periods of education in Bosnia and Herze - govina, as the main text, the principal textbook, as a motivation for logical thinking. That gave me the right to introduce the syntagm Bosnia Porphyriana. SURVEY 109 1. Introduction Man taman ṭaqa tazandaqa. He who practices logic becomes a heretic. 1 It would be impossible to elaborate the development of logic in Bosnia -

Na Osnovu Člana 39. Statuta Grada Sarajeva („Službene Novine Kantona Sarajevo", Broj 34/08 — Prečišćeni Tekst), Gradonačelnik Grada Sarajeva Donosi

BOSNA I HERCEGOVINA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Federacija Bosne i Hercegovine AA Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina KANTON SARAJEVO rin CANTON OF SARAJEVO GRAD SARAJEVO CITY OF SARAJEVO GRADONAČELNIK MAYOR Broj: 01-05-4967/16 Sarajevo, 29.08.2016. godine Na osnovu člana 39. Statuta Grada Sarajeva („Službene novine Kantona Sarajevo", broj 34/08 — prečišćeni tekst), gradonačelnik Grada Sarajeva donosi: ZAKLJUČAK 1. Utvrđuje se Informacija o stanju i održavanju cesta na podru čju grada Sarajevu. 2. Predlaže se Gradskom vijeću Grada Sarajeva da Informaciju o stanju i održavanju cesta na području grada Sarajevu, primi k znanju. GRA NIK Prof..o\ dr. vo Komšić Hamdije Kreševljakovi ća 3, 71000 Sarajevo, BOSNA I HERCEGOVINA Tel. ++387 33 — 208 340; 443 050, Fax: ++387 33 — 208 341 www.sarajevo.ba e-mail: erad(d,saraievo.ba BOSNA I HERCEGOVINA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Federacija Bosne i Hercegovine Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina GRAD SARAJEVO CITY OF SARAJEVO GRADSKO VIJEĆE CITY COUNCIL Broj: Sarajevo, 2016. godine Na osnovu člana 26. stav 1. tačka 2. i člana 74. stav 1. Statuta Grada Sarajeva („Službene novine Kantona Sarajevo", broj 34/08 — prečišćeni tekst), Gradsko vije će Grada Sarajeva, na 42. sjednici održanoj 28.09.2016. godine, primilo je k znanju Informaciju o stanju i održavanju cesta na podru čju grada Sarajevu PREDSJEDAVAJUĆI GRADSKOG VIJEĆA Suljo Agić U1. Hamdije Kreševljakovića 3, 71000 Sarajevo, BOSNA I HERCEGOVINA Tel. ++387 33 — 208 340; Fax: ++387 33 - 208 341; www.sarajevo.ba BOSNA I HERCEGOVINA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Federacija Bosne i Hercegovine Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina KANTON SARAJEVO CANTON OF SARAJEVO GRAD SARAJEVO CITY OF SARAJEVO GRADONAČEINIK MAYOR INFORMACIJA O STANJU I ODRŽAVANJU CESTA NA PODRUČJU GRADA SARAJEVU Predlaga č: Gradona čelnik Obra đivač: Služba za komunalne poslove Sarajevo, septembar 2016. -

![OP]INA STARI GRAD SARAJEVO Op}Insko Vije}E ODLUKU ODLUKU ODLUKU](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1268/op-ina-stari-grad-sarajevo-op-insko-vije-e-odluku-odluku-odluku-301268.webp)

OP]INA STARI GRAD SARAJEVO Op}Insko Vije}E ODLUKU ODLUKU ODLUKU

SLU@BENE NOVINE ^etvrtak, 15. februara 2018. KANTONA SARAJEVO Broj 7 – Strana 83 OP]INA STARI GRAD SARAJEVO Op}insko vije}e Grafi~ki dio sadr`i: Na osnovu ~lana 13. Zakona o principima lokalne - Urbanizam prezentiran na odgovaraju}em broju tematskih samouprave u Federaciji Bosne i Hercegovine ("Slu`bene novine karata, i to: Federacije BiH", broj 49/06 i 51/09), ~lana 25. Statuta Op}ine - karta 1. - Izvod iz Prostornog plana Kantona Stari Grad Sarajevo - Pre~i{}eni tekst ("Slu`bene novine Kantona Sarajeva Sarajevo", broj 20/13), i ~lana 83. i 93. stav (1) Poslovnika - karta 2. - A`urna geodetska podloga Op}inskog vije}a Stari Grad Sarajevo - Pre~i{}eni tekst - karta 3. - In`injersko geolo{ka karta ("Slu`bene novine Kantona Sarajevo", broj 49/17), Op}insko - karta 4. - Postoje}e stanje vije}e Stari Grad Sarajevo je, na sjednici odr`anoj 25. januara - karta 5. - Planirana namjena povr{ina 2018. godine, donijelo - karta 6. - Urbanisti~ko rje{enje - karta 7. - Mre`a regulacionih i gra|evinskih linija ODLUKU - karta 8. - Parterno rje{enje O IZMJENI I DOPUNI ODLUKE O NAKNADAMA I - Idejno rje{enje saobra}aja, DRUGIM PRAVIMA OP]INSKIH VIJE]NIKA I - Idejno rje{enje snabdijevanja vodom i odvodnja otpadnih i ^LANOVA RADNIH TIJELA OP]INSKOG VIJE]A oborinskih voda, - Idejno rje{enje toplifikacije - gasifikacije, STARI GRAD SARAJEVO - Idejno rje{enje energetike i javne rasvjete, ^lan 1. - Idejno rje{enje hortikulture, U Odluci o naknadama i drugim pravima Op}inskih - Idejno rje{enje TK mre`e, vije}nika i ~lanova radnih tijela Op}inskog vije}a Stari Grad - Analiti~ka obrada parcela. -

Travnik – Banja Luka

1ST DAY: ARRIVAL TO SARAJEVO Arrival at Sarajevo Airport and transfer to hotel. Sarajevo is the capital and cultural center of Bosnia and Herzegovina and it is one of the most compelling cities in the Balkans. This warm and welcoming destination has a rich history and it presents one of the most diverse cultures in Europe. The city retains a particular, arresting charm with its abundance of busy café's and abiding tradition of hospitality. Check in and overnight at hotel. 2ND DAY: SARAJEVO Meeting with local guide in the morning and start of guided city tour. Walking through Sarajevo you will see Princip Bridge (site of 1914 assassination of Archduke Ferdinand), Careva Mosque, Gazi Husrev Bey Mosque (one of finest examples of Ottoman architecture in Balkans) and many other sites. Have a walk through Baščaršija, Sarajevo’s old bazaar - a noisy and smoky neighbourhood, which bursts with ancient Ottoman monuments. Here is where you’ll find the best cevapcici, and coffee, too. Optional: Visit War Tunnel to get the real picture of what the War/Siege in Sarajevo was. 3RD DAY: SARAJEVO – VISOKO – TRAVNIK – BANJA LUKA On third day we travel north. First we make a stop in Visoko, which is today a Bosnian Valley of the Pyramids. We continue to Travnik - town rich with cultural and historical heritage. We check up one of the best preserved Ottoman forts in country and see stunningly beautiful spring of Plava Voda (“blue water”). After explorations of Travnik, continue to Banja Luka. Arrival, check in at hotel and overnight. Uniline d.o.o. -

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

UNITED NATIONS CERD International Convention on Distr. the Elimination GENERAL of all Forms of CERD/C/BIH/7-8 Racial Discrimination 21 April 2009 Original: ENGLISH COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION REPORTS SUBMITTED BY STATES PARTIES UNDER ARTICLE 9 OF THE CONVENTION Eighth periodic reports of States parties due in 2008* BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA** *** [25 August 2008] * This document contains the seventh and eighth periodic reports of Bosnia and Herzegovina, due on 16 July 2008, submitted in one document. For the initial to the sixth periodic reports and the summary records of the meetings at which the Committee considered the report, see document CERD/C/464/Add.1, CERD/C/SR.1735, 1736, 1754 and 1755. ** In accordance with the information transmitted to States parties regarding the processing of their reports, the present document was not edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. *** The annexes to the report may be consulted in the files of the secretariat. GE.09-41663 (E) 050509 CERD/C/BIH/7-8 page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Introduction .................................................................................................... 1 - 5 3 Recommendation No. 8 ................................................................................. 6 - 11 3 Recommendation No. 9 ................................................................................. 12 - 23 5 Recommendation No. 10 ............................................................................... 24 - 28 7 Recommendation -

THE POSAVINA BORDER REGION of CROATIA and BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA: DEVELOPMENT up to 1918 (With Special Reference to Changes in Ethnic Composition)

THE POSAVINA BORDER REGION OF CROATIA AND BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA: DEVELOPMENT UP TO 1918 (with special reference to changes in ethnic composition) Ivan CRKVEN^I] Zagreb UDK: 94(497.5-3 Posavina)''15/19'':323.1 Izvorni znanstveni rad Primljeno: 9. 9. 2003. After dealing with the natural features and social importance of the Posavina region in the past, presented is the importance of this region as a unique Croatian ethnic territory during the Mid- dle Ages. With the appearance of the Ottomans and especially at the beginning of the 16th century, great ethnic changes oc- cured, primarily due to the expulsion of Croats and arrival of new ethnic groups, mostly Orthodox Vlachs and later Muslims and ethnic Serbs. With the withdrawal of the Ottomans from the Pannonian basin to the areas south of the Sava River and the Danube, the Sava becomes the dividing line creating in its border areas two socially and politically different environments: the Slavonian Military Frontier on the Slavonian side and the Otto- man military-frontier system of kapitanates on the Bosnian side. Both systems had a special influence on the change of ethnic composition in this region. With the withdrawal of the Ottomans further towards the southeast of Europe and the Austrian occu- pation of Bosnia and Herzegovina the Sava River remains the border along which, especially on the Bosnian side, further changes of ethnic structure occured. Ivan Crkven~i}, Ilo~ka 34, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia. E-mail: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The research subject in this work is the border region Posavi- na between the Republic of Croatia and the Republic Bosnia- 293 -Herzegovina.