FOMC Meeting Transcript, January 24-25, 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EATON 2019 Proxy Statement and Notice of Meeting 9

Proposal 1: Election of Directors —Our Nominees Gregory R. Page Retired Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Cargill Gregory R. Page is the retired Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Cargill, an international marketer, processor and distributor of agricultural, food, financial and industrial products and services. He was named Corporate Vice President & Sector President, Financial Markets and Red Meat Group of Cargill in 1998, Corporate Executive Vice President, Financial Markets and Red Meat Group in 1999, and President and Chief Operating Officer in 2000. He became Chairman and Chief Executive Officer in 2007 and was named Executive Chairman in 2013. Mr. Page served as Executive Director from 2015 to 2016, after which he retired from the Cargill Board. Mr. Page is a director of 3M and Deere & Company and is a member of the Advisory Committee of the Agriculture Division of DowDuPont, Corteva. He is past Chairman and current board member of Big Brothers Big Sisters of America. Mr. Page is a former Director since 2003 director of Carlson and the immediate past President and a board member of the Northern Star Council Age 67 of the Boy Scouts of America. He is a member of the board of the American Refugee Committee. Director Qualifications: As the retired Chairman and former Chief Executive Officer of one of the largest global corporations, Mr. Page brings extensive leadership and global business experience, in-depth knowledge of commodity markets, and a thorough familiarity with the key operating processes of a major corporation, including financial systems and processes, global market dynamics and succession management. Mr. -

US FEDERAL RESERVE in FOCUS Who Matters in the FOMC?

US FEDERAL RESERVE IN FOCUS Who Matters In The FOMC? Sensing the Fed is finally on the cusp of normalizing pol- throughout the last few years) and the QE program com- icy interest rate, there will be a sharper intensity in mar- ing to an end in the next FOMC meeting on 28-29 Oct 2014, ket’s Fed watching, not just about the FOMC decisions the market is sensing that the Fed is finally on the cusp of and the minutes, and also Fed officials’ commentary. normalizing the FFTR. The market consensus is currently ex- pecting the Fed’s rate-lift off to take place in the summer of A recent St. Louis Fed report highlighted that between 2015 (we are expecting it to be announced in the 16-17 June 2008 and 2014, the Fed Reserve bank presidents ac- 2015 FOMC). Thus, there is increasingly intense interest in Fed counted for all of the dissents since 2008 which is un- watching, both in terms of the FOMC decisions & minutes as usual according to the authors. In prior years, both Fed well as the comments from senior Fed Reserve officials that Presidents and Fed Board Governors dissented. are participants in the FOMC (voters and non-voters). In 2014 FOMC decisions so far, Charles Plosser and Rich- First, it is instructive to have a bit of background to the mon- ard Fishers are the key dissenters. And we believe that etary policy formulation process within the US Federal Re- they may be joined by Loretta Mester in the dissent serve. -

The Many Panics of 1837 People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis

The Many Panics of 1837 People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis In the spring of 1837, people panicked as financial and economic uncer- tainty spread within and between New York, New Orleans, and London. Although the period of panic would dramatically influence political, cultural, and social history, those who panicked sought to erase from history their experiences of one of America’s worst early financial crises. The Many Panics of 1837 reconstructs the period between March and May 1837 in order to make arguments about the national boundaries of history, the role of information in the economy, the personal and local nature of national and international events, the origins and dissemination of economic ideas, and most importantly, what actually happened in 1837. This riveting transatlantic cultural history, based on archival research on two continents, reveals how people transformed their experiences of financial crisis into the “Panic of 1837,” a single event that would serve as a turning point in American history and an early inspiration for business cycle theory. Jessica M. Lepler is an assistant professor of history at the University of New Hampshire. The Society of American Historians awarded her Brandeis University doctoral dissertation, “1837: Anatomy of a Panic,” the 2008 Allan Nevins Prize. She has been the recipient of a Hench Post-Dissertation Fellowship from the American Antiquarian Society, a Dissertation Fellowship from the Library Company of Philadelphia’s Program in Early American Economy and Society, a John E. Rovensky Dissertation Fellowship in Business History, and a Jacob K. Javits Fellowship from the U.S. -

Antebellum Banking Regulation: a Comparative Approach

ANTEBELLUM BANKING REGULATION: A COMPARATIVE APPROACH DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alka Gandhi, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Richard H. Steckel, Advisor Professor Paul Evans ________________________ Advisor Professor J. Huston McCulloch Economics Graduate Program ABSTRACT Extensive historical and contemporary studies establish important links between financial systems and economic development. Despite the importance of this research area and the extent of prior efforts, numerous interesting questions remain about the consequences of alternative regulatory regimes for the health of the financial sector. As a dynamic period of economic and financial evolution, which was accompanied by diverse banking regulations across states, the antebellum era provides a valuable laboratory for study. This dissertation utilizes a rich data set of balance sheets from antebellum banks in four U.S. states, Massachusetts, Ohio, Louisiana and Tennessee, to examine the relative impacts of preventative banking regulation on bank performance. Conceptual models of financial regulation are used to identify the motivations behind each state’s regulation and how it changed over time. Next, a duration model is employed to model the odds of bank failure and to determine the impact that regulation had on the ability of a bank to remain in operation. Finally, the estimates from the duration model are used to perform a counterfactual that assesses the impact on the odds of bank failure when imposing one state’s regulation on another state, ceteris paribus. The results indicate that states did enact regulation that was superior to alternate contemporaneous banking regulation, with respect to the ability to maintain the banking system. -

Alaska Roads Historic Overview

Alaska Roads Historic Overview Applied Historic Context of Alaska’s Roads Prepared for Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities February 2014 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Alaska Roads Historic Overview Applied Historic Context of Alaska’s Roads Prepared for Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities Prepared by www.meadhunt.com and February 2014 Cover image: Valdez-Fairbanks Wagon Road near Valdez. Source: Clifton-Sayan-Wheeler Collection; Anchorage Museum, B76.168.3 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Table of Contents Table of Contents Page Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Project background ............................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Purpose and limitations of the study ................................................................................... 3 1.3 Research methodology ....................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Historic overview ................................................................................................................. 6 2. The National Stage ........................................................................................................................ -

Deciphering Federal Reserve Communication Via Text Analysis of Alternative FOMC Statements ∗

Deciphering Federal Reserve Communication via Text Analysis of Alternative FOMC Statements ∗ Taeyoung Dohy Dongho Songz Shu-Kuei Yangx October 20, 2020 Abstract We apply a natural language processing algorithm to FOMC statements to construct a new measure of monetary policy stance, including the tone and novelty of a policy statement. We exploit cross-sectional variations across alternative FOMC statements to identify the tone (for example, dovish or hawkish) and contrast the current and previous FOMC statements released after Committee meetings to identify the novelty of the announcement. We then use high-frequency bond prices to compute the surprise component of the monetary policy stance. Our text-based estimates of monetary policy surprises are not sensitive to the choice of bond maturities used in estimation, are highly correlated with forward guidance shocks in the literature, and are associated with lower stock returns after unexpected policy tightening. The key advantage of our approach is that we are able to conduct a counterfactual policy evaluation by replacing the released statement with an alternative statement, allowing us to perform a more detailed investigation at the sentence and paragraph level. JEL Classification: E30, E40, E50, G12. Keywords: Alternative FOMC statements, counterfactual policy evaluation, monetary policy stance, text analysis, natural language processing. ∗We thank John Rogers for sharing his dataset on monetary policy shock estimates with us. We thank Kyungmin Kim and Suyong Song as well as seminar participants at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, the Interfed Brown Bag, the KAEA webinar, and National University of Singapore who provided helpful comments. All the remaining errors are ours. -

Maintaining Stability in a Changing Financial System

The Participants TOBIAS ADRIAN JEANNINE AvERSA Senior Economist Economics Writer Federal Reserve Bank of New York Associated Press SHAMSHAD AKHTAR MARTIN H. BARNES Governor Managing Editor, State Bank of Pakistan The Bank Credit Analyst BCA Research LEWIS ALEXANDER Chief Economist CHARLES BEAN Citi Deputy Governor Bank of England HAMAD AL-SAYARI Governor STEVEN BECKNER Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency Senior Correspondent Market News International SINAN ALSHABIBI Governor C. FRED BERGSTEN Central Bank of Iraq Director Peterson Institute for DAVID E. ALTIG International Economics Senior Vice President and Director of Research RICHARD BERNER Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Co-Head, Global Economics Morgan Stanley, Inc. SHUHEI AOKI General Manager for the Americas BRIAN BLACKSTONE Bank of Japan Special Writer Dow Jones Newswires 679 08 Book.indb 679 2/13/09 3:59:24 PM 680 The Participants ALAN BOLLARD JOSÉ R. DE GREGORIO Governor Governor Reserve Bank of New Zealand Central Bank of Chile HENDRIK BROUWER SErvAAS DEROOSE Executive Director Director De Nederlandsche Bank European Commission JAMES B. BULLARD WILLIAM C. DUDLEY President and Chief Executive Vice President Executive Officer Federal Reserve Bank of New York Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ROBERT H. DUGGER MARIA TEODORA CARDOSO Managing Director Member of the Board of Directors Tudor Investment Corporation Bank of Portugal ELIZABETH A. DUKE MARK CARNEY Governor Governor Board of Governors of the Bank of Canada Federal Reserve System JOHN CASSIDY CHARLES L. EvANS Staff Writer President and Chief The New Yorker Executive Officer Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago LUC COENE Deputy Governor MARK FELSENTHAL National Bank of Belgium Correspondent Reuters LU CÓRDOVA Chief Executive Officer MIGUEL FERNÁNDEZ Corlund Industries OrDÓÑEZ Governor ANDREW CROCKETT Bank of Spain President JPMorgan Chase International CAMDEN R. -

Building a Better Mousetrap: Patenting

GIVE LINCOLN CREDIT: HOW PAYING FOR THE CIVIL WAR TRANSFORMED THE UNITED STATES FINANCIAL SYSTEM Jenny Wahl* INTRODUCTION .............................................................................701 I. THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM LINCOLN INHERITED AND WHAT HE THOUGHT ABOUT IT ......................................................701 A. Lincoln’s Views of the Shortcomings of the Independent Treasury .................................................702 B. Fractional-Reserve Banks: Benefits and Costs ............. 705 C. Lincoln’s Desires for Development, Sound Currency, and Functional Credit .................................................705 II. PAYING FOR THE WAR .............................................................707 A. Initial Conditions .........................................................708 B. Lincoln’s Options ..........................................................709 1. Taxes and Debt .......................................................709 2. Money Creation ......................................................711 C. Lincoln’s Choices ..........................................................713 1. Taxes: Too Little, Too Late .....................................713 2. Debt: A Strain on the Financial System ................ 714 3. Solution: Greenbacks Plus a New Regime for Money and Banking ...............................................717 D. How Influential Was Lincoln in Financial Matters? ... 719 1. Lincoln Leads Chase ..............................................719 2. Lincoln Guides Congress ........................................721 -

Central Banking in a Democratic Society**

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons DE ECONOMIST 146, NO. 2, 1998 CENTRAL BANKING IN A DEMOCRATIC SOCIETY** BY JOSEPH STIGLITZ* Key words: monetary policy, central bank independence 1 INTRODUCTION AND MAIN CONCLUSIONS It is a special pleasure for me to be here to give this lecture to honor Professor Tinbergen, because his many interests coincide so closely with my own. He spent much of his later life working on the economics of income distribution, a subject with which I began my professional life in my doctoral dissertation, and which has continued to be a focus of my concern. Tinbergen’s thesis that the relative wages of skilled and unskilled workers depend on both supply and demand fac- tors resonates throughout my work on optimal taxation.1 Its importance has been borne out dramatically in wage movements in the United States and elsewhere during the past two decades. From my present vantage point, I am especially appreciative of his devotion to the economics of development, which became the focus of his concern in the mid-1950s, in order, as Tinbergen ~1988! explained in retrospect, ‘to contribute to what seemed to me the highest priority from a humanitarian standpoint.’ But today, I want to focus on other aspects of his work: his contribution to economic policy, particularly the problems of controlling the economy, the rela- tionship between instruments and objectives, and the scope for decentralization, which absorbed him and earned him international recognition in his early days. -

Deciphering the Fed Communication Via Text-Analysis of Alternative FOMC Statements ∗

Deciphering the Fed Communication via Text-Analysis of Alternative FOMC Statements ∗ Taeyoung Dohy Dongho Songz Shu-Kuei Yangx March 18, 2020 Abstract We construct a novel measure of monetary policy stance by relying on a natural lan- guage processing algorithm that enables identification of subtle differences in the tone across alternative FOMC statements, available from March 2004. High-frequency bond prices are used as instruments to tease out the surprise component of monetary policy stance. We find that our text-based monetary policy surprises are highly correlated with forward guidance shocks in the existing literature. According to our measures, an unexpected one-standard-deviation monetary policy tightening reduces stock market return by 20 bps on average, implying that the FOMC's communication was largely effective in moving stock prices in the intended direction. Leveraging the ability of text-analysis to quantify the impact of changing a particular sentence in policy state- ments, we evaluate the (counterfactual) implication of alternative policy prescriptions on the financial markets. JEL Classification: G12, E30, E40, E50. Keywords: Alternative FOMC statements, counterfactual policy evaluation, monetary policy stance, text analysis, natural language processing. ∗We thank John Rogers for sharing his dataset on monetary policy shock estimates with us. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or Federal Reserve System. yFederal Reserve Bank of Kansas City; [email protected] zCarey Business School, Johns Hopkins University; [email protected] xFederal Reserve Bank of Kansas City; [email protected] 1 1 Introduction Central banks have increasingly relied on public communications to provide guidance re- garding future policy actions, e.g., Woodford(2005) and Blinder et al.(2008). -

Bernanke Visits Biotechnology Site in Oakland Thursday, October 14, 2010 by Erich Schwartzel-Pittsburgh Post Gazette

Bernanke visits biotechnology site in Oakland Thursday, October 14, 2010 By Erich Schwartzel-Pittsburgh Post Gazette Lake Fong/Post-Gazette Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke, right, checks out a snaking robot camera made by Cardiorobotics Inc. that's used in minimally invasive surgical procedures. Looking on in South Oakland are three company executives, from left to right, CEO Samuel Straface, vice president Kevin Gilmartin and director of clinical application Richard Kuenzler Say what you will about the economic crisis, but it’s done amazing things for Ben Bernanke's celebrity. In what other economic environment would hallways fill with paparazzi ready to catch the chairman of the Federal Reserve? When else would national cable stations send two teams of reporters to track a former Princeton professor? Boom mics almost outnumbered Secret Service earpieces when Mr. Bernanke stopped Wednesday for two hours at the Pittsburgh Life Sciences Greenhouse. He's in town for a meeting today between the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland and the Fed's Pittsburgh branch, and the listening-tour portion of his trip started at the Greenhouse, a local incubator program for biotechnology companies. But drastic economic measures like stimulus funding and bank bailouts have transformed the Fed chairman from a bureaucratic mainstay into a political operative, equal parts prophet and punching bag. Indeed, if Wednesday's discussion was any proof, Mr. Bernanke now presides over a nation of nervous entrepreneurs ready to question his every decision -- even if he's in the same room. A quiet tour of four Greenhouse-assisted companies was followed by a lively discussion on the problems executives face in a national credit crunch. -

Pdfroster of Attendees

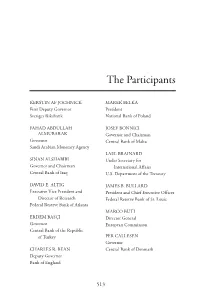

The Participants KERSTIN AF JOCHNICK MAREK BELKA First Deputy Governor President Sveriges Riksbank National Bank of Poland FAHAD ABDULLAH JOSEF BONNICI ALMUBARAK Governor and Chairman Governor Central Bank of Malta Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency LAEL BRAINARD SINAN ALSHABIBI Under Secretary for Governor and Chairman International Affairs Central Bank of Iraq U.S. Department of the Treasury DAVID E. ALTIG JAMES B. BULLARD Executive Vice President and President and Chief Executive Officer Director of Research Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta MARCO BUTI ERDEM BASÇI Director General Governor European Commission Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey PER CALLESEN Governor CHARLES R. BEAN Central Bank of Denmark Deputy Governor Bank of England 513 514 The Participants AGUSTÍN CARSTENS DOUGLAS W. ELMENDORF Governor Director Bank of Mexico Congressional Budget Office NORMAN CHAN WILLIAM B. ENGLISH Chief Executive Director of Monetary Affairs Hong Kong Monetary Authority Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System LUC COENE Governor CHARLES L. EVANS National Bank of Belgium President and Chief Executive Officer Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago JULIA LYNN CORONADO Chief Economist for North America MARTIN FELDSTEIN BNP Paribas President Emeritus, National Bureau of Economic Research CARLOS DA SILVA COSTA Professor, Harvard University Governor Bank of Portugal JACOB A. FRENKEL Chairman CHARLES H. DALLARA JP Morgan Chase International Managing Director Institute of International Finance ARDIAN FULLANI Governor TROY DAVIG Bank of Albania Senior Vice President and Director of Research JOHN GEANAKOPLOS Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Professor Yale University PAUL DEBRUCE CEO and Founder, ESTHER L. GEORGE DeBruce Grain Inc.