FOMC Meeting Transcript, October 29-30, 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EATON 2019 Proxy Statement and Notice of Meeting 9

Proposal 1: Election of Directors —Our Nominees Gregory R. Page Retired Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Cargill Gregory R. Page is the retired Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Cargill, an international marketer, processor and distributor of agricultural, food, financial and industrial products and services. He was named Corporate Vice President & Sector President, Financial Markets and Red Meat Group of Cargill in 1998, Corporate Executive Vice President, Financial Markets and Red Meat Group in 1999, and President and Chief Operating Officer in 2000. He became Chairman and Chief Executive Officer in 2007 and was named Executive Chairman in 2013. Mr. Page served as Executive Director from 2015 to 2016, after which he retired from the Cargill Board. Mr. Page is a director of 3M and Deere & Company and is a member of the Advisory Committee of the Agriculture Division of DowDuPont, Corteva. He is past Chairman and current board member of Big Brothers Big Sisters of America. Mr. Page is a former Director since 2003 director of Carlson and the immediate past President and a board member of the Northern Star Council Age 67 of the Boy Scouts of America. He is a member of the board of the American Refugee Committee. Director Qualifications: As the retired Chairman and former Chief Executive Officer of one of the largest global corporations, Mr. Page brings extensive leadership and global business experience, in-depth knowledge of commodity markets, and a thorough familiarity with the key operating processes of a major corporation, including financial systems and processes, global market dynamics and succession management. Mr. -

US FEDERAL RESERVE in FOCUS Who Matters in the FOMC?

US FEDERAL RESERVE IN FOCUS Who Matters In The FOMC? Sensing the Fed is finally on the cusp of normalizing pol- throughout the last few years) and the QE program com- icy interest rate, there will be a sharper intensity in mar- ing to an end in the next FOMC meeting on 28-29 Oct 2014, ket’s Fed watching, not just about the FOMC decisions the market is sensing that the Fed is finally on the cusp of and the minutes, and also Fed officials’ commentary. normalizing the FFTR. The market consensus is currently ex- pecting the Fed’s rate-lift off to take place in the summer of A recent St. Louis Fed report highlighted that between 2015 (we are expecting it to be announced in the 16-17 June 2008 and 2014, the Fed Reserve bank presidents ac- 2015 FOMC). Thus, there is increasingly intense interest in Fed counted for all of the dissents since 2008 which is un- watching, both in terms of the FOMC decisions & minutes as usual according to the authors. In prior years, both Fed well as the comments from senior Fed Reserve officials that Presidents and Fed Board Governors dissented. are participants in the FOMC (voters and non-voters). In 2014 FOMC decisions so far, Charles Plosser and Rich- First, it is instructive to have a bit of background to the mon- ard Fishers are the key dissenters. And we believe that etary policy formulation process within the US Federal Re- they may be joined by Loretta Mester in the dissent serve. -

Maintaining Stability in a Changing Financial System

The Participants TOBIAS ADRIAN JEANNINE AvERSA Senior Economist Economics Writer Federal Reserve Bank of New York Associated Press SHAMSHAD AKHTAR MARTIN H. BARNES Governor Managing Editor, State Bank of Pakistan The Bank Credit Analyst BCA Research LEWIS ALEXANDER Chief Economist CHARLES BEAN Citi Deputy Governor Bank of England HAMAD AL-SAYARI Governor STEVEN BECKNER Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency Senior Correspondent Market News International SINAN ALSHABIBI Governor C. FRED BERGSTEN Central Bank of Iraq Director Peterson Institute for DAVID E. ALTIG International Economics Senior Vice President and Director of Research RICHARD BERNER Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Co-Head, Global Economics Morgan Stanley, Inc. SHUHEI AOKI General Manager for the Americas BRIAN BLACKSTONE Bank of Japan Special Writer Dow Jones Newswires 679 08 Book.indb 679 2/13/09 3:59:24 PM 680 The Participants ALAN BOLLARD JOSÉ R. DE GREGORIO Governor Governor Reserve Bank of New Zealand Central Bank of Chile HENDRIK BROUWER SErvAAS DEROOSE Executive Director Director De Nederlandsche Bank European Commission JAMES B. BULLARD WILLIAM C. DUDLEY President and Chief Executive Vice President Executive Officer Federal Reserve Bank of New York Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ROBERT H. DUGGER MARIA TEODORA CARDOSO Managing Director Member of the Board of Directors Tudor Investment Corporation Bank of Portugal ELIZABETH A. DUKE MARK CARNEY Governor Governor Board of Governors of the Bank of Canada Federal Reserve System JOHN CASSIDY CHARLES L. EvANS Staff Writer President and Chief The New Yorker Executive Officer Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago LUC COENE Deputy Governor MARK FELSENTHAL National Bank of Belgium Correspondent Reuters LU CÓRDOVA Chief Executive Officer MIGUEL FERNÁNDEZ Corlund Industries OrDÓÑEZ Governor ANDREW CROCKETT Bank of Spain President JPMorgan Chase International CAMDEN R. -

Bernanke Visits Biotechnology Site in Oakland Thursday, October 14, 2010 by Erich Schwartzel-Pittsburgh Post Gazette

Bernanke visits biotechnology site in Oakland Thursday, October 14, 2010 By Erich Schwartzel-Pittsburgh Post Gazette Lake Fong/Post-Gazette Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke, right, checks out a snaking robot camera made by Cardiorobotics Inc. that's used in minimally invasive surgical procedures. Looking on in South Oakland are three company executives, from left to right, CEO Samuel Straface, vice president Kevin Gilmartin and director of clinical application Richard Kuenzler Say what you will about the economic crisis, but it’s done amazing things for Ben Bernanke's celebrity. In what other economic environment would hallways fill with paparazzi ready to catch the chairman of the Federal Reserve? When else would national cable stations send two teams of reporters to track a former Princeton professor? Boom mics almost outnumbered Secret Service earpieces when Mr. Bernanke stopped Wednesday for two hours at the Pittsburgh Life Sciences Greenhouse. He's in town for a meeting today between the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland and the Fed's Pittsburgh branch, and the listening-tour portion of his trip started at the Greenhouse, a local incubator program for biotechnology companies. But drastic economic measures like stimulus funding and bank bailouts have transformed the Fed chairman from a bureaucratic mainstay into a political operative, equal parts prophet and punching bag. Indeed, if Wednesday's discussion was any proof, Mr. Bernanke now presides over a nation of nervous entrepreneurs ready to question his every decision -- even if he's in the same room. A quiet tour of four Greenhouse-assisted companies was followed by a lively discussion on the problems executives face in a national credit crunch. -

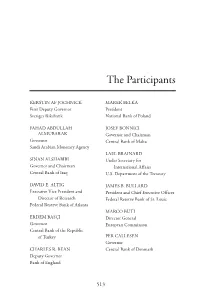

Pdfroster of Attendees

The Participants KERSTIN AF JOCHNICK MAREK BELKA First Deputy Governor President Sveriges Riksbank National Bank of Poland FAHAD ABDULLAH JOSEF BONNICI ALMUBARAK Governor and Chairman Governor Central Bank of Malta Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency LAEL BRAINARD SINAN ALSHABIBI Under Secretary for Governor and Chairman International Affairs Central Bank of Iraq U.S. Department of the Treasury DAVID E. ALTIG JAMES B. BULLARD Executive Vice President and President and Chief Executive Officer Director of Research Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta MARCO BUTI ERDEM BASÇI Director General Governor European Commission Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey PER CALLESEN Governor CHARLES R. BEAN Central Bank of Denmark Deputy Governor Bank of England 513 514 The Participants AGUSTÍN CARSTENS DOUGLAS W. ELMENDORF Governor Director Bank of Mexico Congressional Budget Office NORMAN CHAN WILLIAM B. ENGLISH Chief Executive Director of Monetary Affairs Hong Kong Monetary Authority Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System LUC COENE Governor CHARLES L. EVANS National Bank of Belgium President and Chief Executive Officer Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago JULIA LYNN CORONADO Chief Economist for North America MARTIN FELDSTEIN BNP Paribas President Emeritus, National Bureau of Economic Research CARLOS DA SILVA COSTA Professor, Harvard University Governor Bank of Portugal JACOB A. FRENKEL Chairman CHARLES H. DALLARA JP Morgan Chase International Managing Director Institute of International Finance ARDIAN FULLANI Governor TROY DAVIG Bank of Albania Senior Vice President and Director of Research JOHN GEANAKOPLOS Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Professor Yale University PAUL DEBRUCE CEO and Founder, ESTHER L. GEORGE DeBruce Grain Inc. -

FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Twentieth Street and Constitution Avenue NW., Washington, DC 20551 Phone, 202–452–3000

404 U.S. GOVERNMENT MANUAL Activities Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Cases brought before the Commission Government Printing Office, are assigned to the Office of Washington, DC 20402. The Administrative Law Judges, and hearings Commission’s Web site includes recent are conducted pursuant to the decisions, a searchable database of requirements of the Administrative previous decisions, procedural rules, Procedure Act (5 U.S.C. 554, 556) and audio recordings of recent public the Commission’s procedural rules (29 meetings, and other pertinent CFR 2700). information. A judge’s decision becomes a final but nonprecedential order of the Requests for Commission records should Commission 40 days after issuance be submitted in accordance with the unless the Commission has directed the Commission’s Freedom of Information case for review in response to a petition Act regulations. Other information, or on its own motion. If a review is including Commission rules of procedure conducted, a decision of the and brochures explaining the Commission becomes final 30 days after Commission’s functions, is available issuance unless a party adversely from the Executive Director, Federal affected seeks review in the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Mine Safety and Health Review Columbia or the Circuit within which Commission, 601 New Jersey Avenue the mine subject to the litigation is NW., Suite 9500, Washington, DC located. 20001–2021. Internet, www.fmshrc.gov. As far as practicable, hearings are held Email, [email protected]. at locations convenient to the affected For information on filing requirements, mines. In addition to its Washington, the status of cases before the DC, offices, the Office of Administrative Law Judges maintains an office in the Commission, or docket information, Colonnade Center, Room 280, 1244 contact the Office of General Counsel or Speer Boulevard, Denver, CO 80204. -

1 in the United States District Court For

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS MARSHALL DIVISION LEON STAMBLER, § § Plaintiff, § § v. § § FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ATLANTA, § FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON, § FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF CHICAGO, § FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF § Civil Action No. 2:12-cv-611 CLEVELAND, FEDERAL RESERVE BANK § OF DALLAS, FEDERAL RESERVE BANK § OF KANSAS CITY, FEDERAL RESERVE § JURY TRIAL DEMANDED BANK OF MINNEAPOLIS, FEDERAL § RESERVE BANK OF NEW YORK, § FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF § PHILADELPHIA, FEDERAL RESERVE § BANK OF RICHMOND, FEDERAL § RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO, and § FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST. LOUIS, § § Defendants. § PLAINTIFF’S ORIGINAL COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiff LEON STAMBLER files this Original Complaint against the above-named Defendants, alleging as follows: I. THE PARTIES 1. Plaintiff LEON STAMBLER (“Stambler”) is an individual residing in Parkland, Florida. 2. On information and belief, Defendant FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ATLANTA is a corporation organized and existing under the laws of the United States of America, with its principal place of business in Atlanta, Georgia. This Defendant may be served 1 with process by and through its President and CEO at Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, c/o Dennis P. Lockhart, 1000 Peachtree Street, N.E., Atlanta, Georgia 30309. 3. On information and belief, Defendant FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON is a corporation organized and existing under the laws of the United States of America, with its principal place of business in Boston, Massachusetts. This Defendant may be served with process by and through its President and CEO at Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, c/o Eric S. Rosengren, 600 Atlantic Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02210-2204. -

FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Twentieth Street and Constitution Avenue NW., Washington, DC 20551 Phone, 202–452–3000

420 U.S. GOVERNMENT MANUAL FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Twentieth Street and Constitution Avenue NW., Washington, DC 20551 Phone, 202–452–3000. Internet, www.federalreserve.gov. Board of Governors Chairman ALAN GREENSPAN Vice Chair ROGER W. FERGUSON, JR. Members EDWARD M. GRAMLICH, SUSAN SCHMIDT BIES, MARK W. OLSON, BEN S. BERNANKE, DONALD L. KOHN Staff: Assistants to the Board WINTHROP P. HAMBLEY, MICHELLE A. SMITH General Counsel J. VIRGIL MATTINGLY, JR. Secretary JENNIFER J. JOHNSON Director, Division of Banking Supervision and RICHARD SPILLENKOTHEN Regulation Director, Division of Consumer and DOLORES S. SMITH Community Affairs Director, Division of Federal Reserve Bank LOUISE L. ROSEMAN Operations and Payment Systems Director, Division of Information Resources MARIANNE M. EMERSON Management Director, Division of International Finance KAREN H. JOHNSON Director, Management Division H. FAY PETERS, Acting Director, Division of Monetary Affairs VINCENT R. REINHART Director, Division of Research and Statistics DAVID J. STOCKTON Staff Director, Office of Staff Director for STEPHEN R. MALPHRUS Management Inspector General BARRY R. SNYDER Officers of the Federal Reserve Banks Chairmen and Federal Reserve Agents: Atlanta, GA DAVID M. RATCLIFFE Boston, MA SAMUEL O. THIER Chicago, IL W. JAMES FARRELL Cleveland, OH ROBERT W. MAHONEY Dallas, TX RAY L. HUNT Kansas City, MO RICHARD H. BARD Minneapolis, MN LINDA HALL WHITMAN New York, NY JOHN E. SEXTON Philadelphia, PA RONALD J. NAPLES Richmond, VA WESLEY S. WILLIAMS, JR. St. Louis, MO WALTER L. METCALFE, JR. San Francisco, CA GEORGE M. SCALISE Presidents: Atlanta, GA JACK GUYNN Boston, MA CATHY E. MINEHAN Chicago, IL MICHAEL H. -

Federal Open Market Committee Communication: a Text Mining Analysis

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 5-2019 Federal Open Market Committee communication: a text mining analysis Jonathan Stegmann University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation Stegmann, Jonathan, "Federal Open Market Committee communication: a text mining analysis" (2019). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Federal Open Market Committee Communications: A Text Mining Analysis Jonathan Stegmann Honors College Thesis The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Examination Date: 3/25/19 Beni Asllani, Ph.D. Bento J. Lobo, Ph.D., CFA Marvin E. White First Tennessee Bank Distinguished Professor of Management Professor of Finance Department Examiner Thesis Director Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................ 1 I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 2 II. Literature Review ......................................................................................................................... -

FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Twentieth Street and Constitution Avenue NW., Washington, DC 20551 Phone, 202–452–3000

418 U.S. GOVERNMENT MANUAL Sources of Information and brochures explaining the Commission decisions are published Commission’s functions, is available bimonthly and are available through the from the Executive Director, Federal Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Mine Safety and Health Review Government Printing Office, Commission, 601 New Jersey Avenue Washington, DC 20402. The NW., Suite 9500, Washington, DC Commission’s Web site includes recent 20001–2021. E-mail, [email protected]. decisions, a searchable database of For information on filing requirements, previous decisions, procedural rules, the status of cases before the audio recordings of recent public meetings, and other pertinent Commission, or docket information, information. contact the Office of General Counsel or Requests for Commission records should the Docket Office, Federal Mine Safety be submitted in accordance with the and Health Review Commission, 601 Commission’s Freedom of Information New Jersey Avenue, NW., Suite 9500, Act regulations. Other information, Washington, DC 20001. E-mail, including Commission rules of procedure [email protected]. For further information, contact the Executive Director, Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission, 601 New Jersey Avenue NW., Suite 9500, Washington DC 20001–2021. Phone, 202–434– 9905. Fax, 202–434–9906. Internet, www.fmshrc.gov. E-mail, [email protected]. FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Twentieth Street and Constitution Avenue NW., Washington, DC 20551 Phone, 202–452–3000. Internet, www.federalreserve.gov. Board of Governors Chairman BEN S. BERNANKE Vice Chairman DONALD L. KOHN Members SUSAN SCHMIDT BIES, RANDALL S. KROSZNER, KEVIN M. WARSH Staff: Director, Division of Board Members MICHELLE A. -

FOMC Minutes, January 28-29, 2014

_____________________________________________________________________________________________Page 1 Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee January 28–29, 2014 A meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee was Nellie Liang, Director, Office of Financial Stability Pol- held in the offices of the Board of Governors of the icy and Research, Board of Governors Federal Reserve System in Washington, D.C., on Tuesday, January 28, 2014, at 2:00 p.m. and continued Stephen A. Meyer and William Nelson, Deputy Direc- on Wednesday, January 29, 2014, at 9:00 a.m. tors, Division of Monetary Affairs, Board of Gov- ernors PRESENT: Ben Bernanke, Chairman Jon W. Faust, Special Adviser to the Board, Office of William C. Dudley, Vice Chairman Board Members, Board of Governors Richard W. Fisher Narayana Kocherlakota Linda Robertson and David W. Skidmore, Assistants to Sandra Pianalto the Board, Office of Board Members, Board of Charles I. Plosser Governors Jerome H. Powell Jeremy C. Stein Trevor A. Reeve, Senior Associate Director, Division Daniel K. Tarullo of International Finance, Board of Governors Janet L. Yellen Joyce K. Zickler, Senior Adviser, Division of Monetary Christine Cumming, Charles L. Evans, Jeffrey M. Lack- Affairs, Board of Governors er, Dennis P. Lockhart, and John C. Williams, Al- ternate Members of the Federal Open Market Daniel M. Covitz and Michael T. Kiley, Associate Di- Committee rectors, Division of Research and Statistics, Board of Governors James Bullard, Esther L. George, and Eric Rosengren, Presidents of the Federal Reserve Banks of St. Jane E. Ihrig, Deputy Associate Director, Division of Louis, Kansas City, and Boston, respectively Monetary Affairs, Board of Governors William B. -

Global Views 10-04-13

GlobalViews Weekly commentary on economic and financial market developments October 4, 2013 Corporate Emerging Fixed Fixed Foreign Economics > Portfolio Strategy Bond Research Markets Strategy > Income Research Income Strategy > Exchange Strategy > Economic Statistics > Financial Statistics > Forecasts > Contact Us > 2-8 Economics 2-3 Stale FOMC Minutes To Remind Markets Of A Close Call .......................................................................Derek Holt 4-5 Global Forecast Update: Cloudy, But With A Greater Chance Of Compromise .........................................Aron Gampel 6 In The Shadow Of The U.S. Debt Ceiling … Again ...............................................................................Mary Webb 7 Bank Of Canada Signals A Policy Hold Into 2016 ...................................................................Derek Holt & Dov Zigler 8 Japan Implements A Consumption Tax Increase For April 2014 ........................................................... Tuuli McCully 9-11 Emerging Markets Strategy Bancolombia Vs. Competitors ..................................................................................... Araceli Espinosa & Joe Kogan 12-16 Fixed Income Strategy UK Bank Of England Meeting Preview (October) ................................................................................. Alan Clarke Euro Political Risk Receding? ...................................................................................................... Frédéric Prêtet 17-18 Foreign Exchange Strategy FX Markets Are Driven