Leadership Makes the Difference a Personal Talk with Danny R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redmon Returns Inside This Edition

75¢ VOLUME 07 • NUMBER 23 PSALM 100:3 June 8, 2021 MORGAN COUNTY WEATHER THIS WEEK Moonshine & Mud Veteran of the Week Thomas P. Payne The weekend was packed full of great People came from all over to hole tournament, chili cookoff, bbq sauce things to do in Morgan County. One attend the event. Vendors, food, games, contest, and much more. of those was the Moonshine and Mud crafts, live music, and the Mud Sling were Johnboy says he is ready for next festival hosted by Johnboy’s BBQ at the all a part of the fun. years event to be a 2 day festival to pack Morgan County Fairgrounds. There was a mullet contest, corn- in all the fun. LEO of the Week The Badge Redmon Returns Inside This Edition Obits Page 2 Local Page 3 History Page 4 Games Page 5 Faith, Family Freedom Page 6 American Heritage Page 8 Heroes Page 9 Trending Page 10 After a short rest, Tom We are grateful Redmon has returned to to have him be a part of Like & Follow us writing. He took a short our paper but more im- on Social Media. break just to get some portantly a fixture in the rest but is back bringing Morgan County fabric. you the articles that you He is truly a treasure. enjoy so much. Tuesday, Page 2 In Loving Memory June 8, 2021 Loreen Bunch, 73 Jerry Dean Phillips, 54 Loreen Bunch, age 73 of Devo- Also surviving are several niec- Jerry Dean Phillips, age 54, of wife, Paulette Phillips of Coal- nia passed away at her home es, nephews and other friends Devonia passed away Sunday, field; nephews, Kevin Ward, on Saturday, May 29, 2021. -

FLYING BOATS” in MAINE?

DIRIGO FLYER Newsletter of the Maine Aviation Historical Society Volume XXIV No. 1 January - March 2016 GARY IVAN GORDON – A MAINE HERO Gary Ivan Gordon, a native of Lincoln, Maine was one of two 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta, or Delta Gary Ivan Gordon Force, operators to posthumously receive the Medal of Honor. Bestowed by President Clinton on May 23, 1994, to their widows, these were the first Medals of Honor conferred since the Vietnam war. In an October, 1993, confrontation in Mogadishu, Somalia, surrounded by enemy combatants, the gallantry and self-sacrifice of Gary Gordon and his sniper teammate, Randall Shughart, helped save the life of the Gordon as a Sergeant First Class pilot of a downed Black Hawk helicopter. Nickname(s) "Gordy" Born August 30, 1960 The movie, Black Hawk Down, memorializes Lincoln, Maine the actions of this Maine hero on that day. Died October 3, 1993 (aged 33) For a brief description of the battle, please Mogadishu, Somalia read the official Medal of Honor Citation Place of burial Lincoln Cemetery, reprinted on page 3. Penobscot County, Maine Courtesy of Wikipedia Continued on Page 3 2 The Twilight Zone: It’s here in Maine on I-95! Dirigo Flyer A VISIT TO THE STAR CONNIE Published quarterly by the Maine Aviation Historical Society, This past summer Bob Littlefield and Hank Marois thought that it a non-profit (501c3) corporation Address: PO Box 2641, Bangor, Maine 04402 might be a good idea to have a story in our museum newsletter, The 207-941-6757, 1-877-280-MAHS Dirigo Flyer, about the alleged restoration of the Star Constellation (6247) in state supposedly taking place at the Lewiston-Auburn Airport. -

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE PB 34-09-2 Volume 35 Number 2 April - June 2009

MIPB April - June 2009 PB 34-O9-2 Operations in OEF Afghanistan FROM THE EDITOR In this issue, three articles offer perspectives on operations in Afghanistan. Captain Nenchek dis- cusses the philosophy of the evolving insurgent “syndicates,” who are working together to resist the changes and ideas the Coalition Forces bring to Afghanistan. Captain Beall relates his experiences in employing Human Intelligence Collection Teams at the company level in both Iraq and Afghanistan. Lieutenant Colonel Lawson provides a look into the balancing act U.S. Army chaplains as non-com- batants in Afghanistan are involved in with regards to Information Operations. Colonel Reyes discusses his experiences as the MNF-I C2 CIOC Chief, detailing the problems and solutions to streamlining the intelligence effort. First Lieutenant Winwood relates her experiences in integrating intelligence support into psychological operations. From a doctrinal standpoint, Lieutenant Colonels McDonough and Conway review the evolution of priority intelligence requirements from a combined operations/intelligence view. Mr. Jack Kem dis- cusses the constructs of assessment during operations–measures of effectiveness and measures of per- formance, common discussion threads in several articles in this issue. George Van Otten sheds light on a little known issue on our southern border, that of the illegal im- migration and smuggling activities which use the Tohono O’odham Reservation as a corridor and offers some solutions for combined agency involvement and training to stem the flow. Included in this issue is nomination information for the CSM Doug Russell Award as well as a biogra- phy of the 2009 winner. Our website is at https://icon.army.mil/ If your unit or agency would like to receive MIPB at no cost, please email [email protected] and include a physical address and quantity desired or call the Editor at 520.5358.0956/DSN 879.0956. -

GOTHIC SERPENT Black Hawk Down Mogadishu 1993

RAID GOTHIC SERPENT Black Hawk Down Mogadishu 1993 CLAYTON K.S. CHUN GOTHIC SERPENT Black Hawk Down Mogadishu 1993 CLAYTON K.S. CHUN CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 04 ORIGINS 08 Clans go to War 10 The UN versus Aideed 11 INITIAL STRATEGY 14 Task Force Ranger Forms 15 A Study in Contrasts: US/UN forces and the SNA 17 TFR’s Tactics and Procedures 25 TFR Operations Against Aideed and the SNA 27 PLAN 31 TFR and the QRF Prepare for Action 32 Black Hawks and Little Birds 34 Somali Preparations 35 RAID 38 “Irene”: Going into the “Black Sea” 39 “Super 61’s Going Down” 47 Ground Convoy to the Rescue 51 Super 64 Goes Down 53 Securing Super 61 59 Mounting Another Rescue 60 TFR Hunkers Down for the Night 65 Confusion on National Street 68 TFR Gets Out 70 ANALYSIS 72 CONCLUSION 76 BIBLIOGRAPHY 78 INDEX 80 INTRODUCTION Me and Somalia against the world Me and my clan against Somalia Me and my family against the clan Me and my brother against my family Me against my brother. Somali Proverb In 1992, the United States basked in the glow of its recent military and political victory in Iraq. Washington had successfully orchestrated a coalition of nations, including Arabic states, to liberate Kuwait from Saddam Hussein. The US administration was also celebrating the fall of the Soviet Union and the bright future of President George H.W. Bush’s “New World Order.” The fear of a nuclear catastrophe seemed remote given the international growth of democracy. With the United States now as the sole global superpower, some in the US government felt that it now had the opportunity, will, and capability to reshape the world by creating democratic states around the globe. -

Black Hawk Down

Black Hawk Down A Story of Modern War by Mark Bowden, 1951- Published: 1999 J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents Dedication & The Assault Black Hawk Down Overrun The Alamo N.S.D.Q. Epilogue Sources Acknowledgements J J J J J I I I I I For my mother, Rita Lois Bowden, and in memory of my father, Richard H. Bowden It makes no difference what men think of war, said the judge. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting the ultimate practitioner. Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian The Assault 1 At liftoff, Matt Eversmann said a Hail Mary. He was curled into a seat between two helicopter crew chiefs, the knees of his long legs up to his shoulders. Before him, jammed on both sides of the Black Hawk helicopter, was his „chalk,“ twelve young men in flak vests over tan desert camouflage fatigues. He knew their faces so well they were like brothers. The older guys on this crew, like Eversmann, a staff sergeant with five years in at age twenty-six, had lived and trained together for years. Some had come up together through basic training, jump school, and Ranger school. They had traveled the world, to Korea, Thailand, Central America … they knew each other better than most brothers did. They‘d been drunk together, gotten into fights, slept on forest floors, jumped out of airplanes, climbed mountains, shot down foaming rivers with their hearts in their throats, baked and frozen and starved together, passed countless bored hours, teased one another endlessly about girlfriends or lack of same, driven out in the middle of the night from Fort Benning to retrieve each other from some diner or strip club out on Victory Drive after getting drunk and falling asleep or pissing off some barkeep. -

Bowl Round 3 Bowl Round 3 First Quarter

NHBB A-Set Bowl 2015-2016 Bowl Round 3 Bowl Round 3 First Quarter (1) John Cobb died while on a speedboat in this body of water. The crannog of Cherry Island lies in this body of water, on whose shores lie Urquhart Castle and the town of Port Augustus. The Falls of Foyers feed into this body of water. The \Surgeon's Photograph" was a hoax purportedly depicting a creature that lived in this lake. For ten points, name this Scottish body of water, purportedly home to a cryptocreature named Nessie. ANSWER: Loch Ness (or Lake Ness) (2) Albert Schweitzer won the 1952 Nobel Peace Prize in part for building one of these institutions in Lambar´en´e,Gabon. The poor conditions in one of these buildings in Scutari led Isambard Kingdom Brunel to build a prefabricated one of these that was shipped to Renkioi during the Crimean War. One of these in Kunduz was attacked in 2015; that airstrike was requested by anti-Taliban forces and carried out by the US Air Force. For ten points, name these institutions built in warzones by Doctors Without Borders. ANSWER: hospital (3) This island's native population, known for long, wavy beards, rebelled in Shakushain's Revolt. This island's port of Hakodate [hah-ko-dah-tay] was the capital of its breakway Republic of Ezo. The first Asian Winter Olympics were held on this island at Sapporo. The Seikan Tunnel connects this home of the Ainu people to its southern neighbor, Honshu. The Sea of Okhtosk is north of, for ten points, what northernmost of Japan's four main islands? ANSWER: Hokkaido (4) Marty Glickman claimed that his removal from an Olympic team in favor of this man was a political capitulation by Avery Brundage. -

August 19, 1994

August 19, 1994 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE 23285 The Women's Pre-Qualification Pilot Loan has received a technical assistance grant ORDERS FOR MONDAY, AUGUST 22, Program is designed to streamline the appli- from the American Indian Consultants, Inc., 1994 cation process and provide a quick response U.S. Department of Commerce, to provide to a non-profit intermediary for loan re- marketing services for Santa Fe Coat Com- Mr. SARBANES. Mr. President, on quests of $250,000 or less to women owned pany. behalf of the majority leader, I ask (51% or more) and managed businesses. It fo- Santa Fe Coat Company is an American In- unanimous consent that on Monday, cuses on the character. credit, experience dian owned apparel design, manufacturing following the prayer, the Journal of and reliability of the applicants. "During the and wholesaling business, located at Isleta proceedings be deemed approved to first few weeks that the pilot program has Pueblo, a village that lies 23 miles south of date and the time for the two leaders been in place our office has had many inquir- Albuquerque. New Mexico. Santa Fe Coat ies," Dowell states. "We hope to approve ad- reserved for their use later in the day; Company specializes in American Indian cus- that immediately thereafter, the Sen- ditional loans through this program and our tom designed women's coats, and its concept existing 7(a) guaranteed loan programs in is to produce Indian designed clothing from ate resume consideration of S. 2351, the the near future." drawing room to the finished product. Health Security Act. -

Directive Speech Acts in Black Hawk Down

DIRECTIVE SPEECH ACTS IN BLACK HAWK DOWN Dedi Candra, Devi Rosmawati, Tri Septa Nurhantoro English Literature Study Program, Respati Yogyakarta University ABSTRAK Penelitian ini menganalisa ujaran dari setiap karakter dalam film Black Hawk Down yang difokuskan pada jenis tindak tutur direktif dan pengaruh konteks situasi. Penelitian ini merupakan penelitian deskriptif kualitatif yang menggunakan pendekatan analisis isi. Sebagai bagian instrument penelitian, peneliti menerapkan tindak tutur dari Searle dan teori konteks situasi dari Haliday. Hasil penelitian menunjukan terdapat 369 data tindak tutur direktifyang didominasi jenis command sebanyak 211 data (57.18%), order sejumlah 62 data (16.80%), request sejumlah 55 (14.91%), dan suggestion sejumlah 41 data (11.11%). Ditemukan juga mode „face to face‟ dan tenor Staff Sergeant Matt Eversmann paling sering muncul dalam film, sedangkan field didominasi perang. Kesimpulan yang dapat ditarik yaitu command adalah tindak tutur yang paling mendominasi dalam Black Hawk Down karena objek penelitian adalah film perang, dimana didalamnya prajurit yang memiliki pangkat lebih rendah harus mematuhi perintah dari yang memiliki pangkat lebih tinggi. Kata Kunci: tindak tutur direktif, kontek situasi situational context, film Back Hawk Down A. Introduction Human is created by God with excellent abilities. Human is not only given five senses, human is also given other abilities, like to think and to feel. To share or tell about thought or feeling, people do an interaction with other people by communicating. People can use sign and verbal language in communication. Speaking is a form of direct communication that is done by a speaker by producing utterances and has senses to be understood by the hearer. -

Reimagining the Character of Urban Operations for the U.S. Army: How the Past Can Inform the Present and Future

C O R P O R A T I O N Reimagining the Character of Urban Operations for the U.S. Army How the Past Can Inform the Present and Future Gian Gentile, David E. Johnson, Lisa Saum-Manning, Raphael S. Cohen, Shara Williams, Carrie Lee, Michael Shurkin, Brenna Allen, Sarah Soliman, James L. Doty III For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1602 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9607-4 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The history of human conflict suggests that the U.S. -

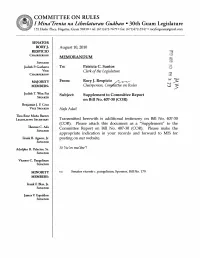

Committee on Rules

COMMITTEE ON RULES I Mina'Trenta na Liheslaturan Guahan • 30th Guam Legislature 155 Hesler Place, Hagatfia, Guam 96910 • tel: (671)472-7679 • fax: (671)472-3547 • [email protected] SENATOR RORYJ. August 10, 2010 RESPICIO CHAIRPERSON MEMORANDUM SENATOR Judith P. Guthertz To: Patricia C. Santos VICE Clerk of the Legislature CHAIRPERSON MAJORITY From: Rory J. Respicio ~ MEMBERS: Chairperson, Co~ittee on Rules Judith T. Won Pat Subject: Supplement to Committee Report SPEAKER on Bill No. 407-30 (COR) Benjamin J. F. Cruz VICE SPEAKER HafaAdai! Tma Rose Mufi.a Barnes LEGISlATIVE SECRETARY Transmitted herewith is additional testimony on Bill No. 407-30 (COR). Please attach this document as a "Supplement" to the Thomas C. Ada Committee Report on Bill No. 407-30 (COR). Please make the SENATOR appropriate indication in your records and forward to MIS for Frank B. Aguon, Jr. posting on our website. SENATOR Adolpho B. Palacios, Sr. Si Yu'os ma'dse'! SENATOR Vicente C. Pangelinan SENATOR MINORITY cc: Senator vicente c. pangelinan, Sponsor, Bill No. 179 MEMBERS: Frank F. Blas, Jr. SENATOR James V. Espaldon SENATOR To: Thirtieth Guam Legislature Date: 08/10/10 Ref: Bill 407 "The Guam Medal of Honor" Dear Senators, It is with profound respect that we the undersigned Veterans below support proposed bill 407 in Honor of all of Guam's sons and daughter who have given their lives in honor of their country, island and people. We thank you Senators for your heartfilled respect and dignity in honoring these soldiers. However, the name "Guam Medal of Honor" needs to be changed to, not confuse or disrespect our nations highest award the ~~congressional Medal of Honor". -

PEGGY COOKE ANDERSON - Died Passed Away Friday, September 16, 2016, in Conway, South Carolina at the Age of 74

PEGGY COOKE ANDERSON - Died passed away Friday, September 16, 2016, in Conway, South Carolina at the age of 74. The cause of death is unknown. She was born in Conway on September 7, 1942, to the late Harry L. and Vera Lorene (née Singleton) Cooke. She was a member of the Sunshine Sunday School Class, First Baptist Conway. She was also a Life Member of Associates of Vietnam Veterans of America – Surfside Beach Chapter #925, DAV, Conway Lioness Club, National Radiological Society, Red Hat Society and the Association for Retarded Citizens. Mrs. Anderson was a 1960 graduate of CHS, as well as, the Conway Hospital School of Radiology, working at both the 9th and Bell Streets location and current Conway Medical Center. Interestingly, she was born at Conway Hospital, graduated from Conway Hospital, got married in the Chapel at Conway Hospital and upon her husbands’ retirement, purchased and moved into the house that was the original Conway Hospital. She also worked for many years at Ocean View and Grand Strand General. She was predeceased by her husband, Captain Thomas J. Anderson (U.S. Army, Ret.), a brother, Mack Cooke and a sister, Lori Nicholson. The family would like to thank her caregivers with Agape Hospice and Carolina Gardens, as well as her church sisters and many friends who visited and checked on her regularly. Surviving are one son, Thomas “Tom” J. Anderson II and his wife, April of Conway, two grandchildren, Caroline Rembrett Anderson and Thomas J. Anderson III, one sister, Susan Githens (Monroe) of Conway, and two nieces, Hannah N. -

Black Hawk Down' Speaks in Chambersburg (Print View) Page 1 of 2

The Herald-Mail ONLINE - Subject of 'Black Hawk Down' speaks in Chambersburg (print view) Page 1 of 2 The Herald-Mail ONLINE http://www.herald-mail.com/ 05/29/2008 Subject of 'Black Hawk Down' speaks in Chambersburg By DON AINES [email protected] CHAMBERSBURG, PA. — Retired Chief Warrant Officer Michael J. Durant knows what it is to be “In the Company of Heroes,” the title of the book he wrote recounting his military career, the most harrowing episode of which was the time he spent as the prisoner of a Somali warlord after his helicopter was shot down over Mogadishu on Oct. 3, Michael J. Durant, right, talks with Franklin 1993. County Area Development Corp. President L. Michael Ross Wednesday at the Letterkenny Business Opportunity That 11-day ordeal was one of the central stories to Mark Bowden’s Showcase. Durant, who survived being shot 1999 best-seller “Black Hawk Down,” as well as the 2001 film version of down and captured in Mogadishu, Somalia, the book, in which Durant was portrayed by Ron Eldard. in 1993, spoke at the dinner about the personal, political and military lessons Before speaking to the 177 guests Wednesday at a dinner kicking off the learned from the battle. (Credit: Don Aines / third Letterkenny Business Opportunity Showcase, Durant sat down and Staff Writer) talked about the lessons he and the military learned from the Battle of Mogadishu. “Look back, but don’t stare” was a piece of personal advice Durant said he has taken to heart. It came in a letter from a cancer survivor, the only member of her support group still alive.