By Lee A. Breakiron the CROMLECHERS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

CFP-Essays on Librarians/Archives/Libraries in Graphic Novels, Comic Strips and Sequential Art

H-Announce CFP-Essays on Librarians/Archives/Libraries in Graphic Novels, Comic Strips and Sequential Art Announcement published by rob weiner on Wednesday, September 2, 2020 Type: Call for Papers Date: November 15, 2020 Location: Texas, United States Subject Fields: Art, Art History & Visual Studies, Cultural History / Studies, Film and Film History, Library and Information Science, Popular Culture Studies Call for Essays: Libraries, Archives, and Librarians in Graphic Novels, Comic Strips and Sequential Art edited by Carrye Syma, Donell Callender, and Robert G. Weiner. The editors of a new collection of articles/essays are seeking essays about the portrayal of libraries, archives and librarians in graphic novels, comic strips, and sequential art/comics. The librarian and the library have a long and varied history in sequential art.Steven M. Bergson’s popular website LIBRARIANS IN COMICS (http://www.ibiblio.org/librariesfaq/comstrp/comstrp.htm; http://www.ibiblio.org/librariesfaq/combks/combks.htm) is a useful reference source and a place to start as is the essay Let’s Talk Comics: Librarians by Megan Halsband (https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2019/07/lets-talk-comics-librarians/). There are also other websites which discuss librarians in comics and provide a place for scholars to start. Going as far back as the Atlantean age the librarian is seen as a seeker of knowledge for its own sake. For example, in Kull # 6 (1972) the librarian is trying to convince King Kull that of importance of gaining more knowledge for the journey they about to undertake. Kull is unconvinced, however. In the graphic novel Avengers No Road Home (2019), Hercules utters “Save the Librarian” which indicates just how important librarians are as gatekeepers of knowledge even for Greek Gods. -

2019-05-06 Catalog P

Pulp-related books and periodicals available from Mike Chomko for May and June 2019 Dianne and I had a wonderful time in Chicago, attending the Windy City Pulp & Paper Convention in April. It’s a fine show that you should try to attend. Upcoming conventions include Robert E. Howard Days in Cross Plains, Texas on June 7 – 8, and the Edgar Rice Burroughs Chain of Friendship, planned for the weekend of June 13 – 15. It will take place in Oakbrook, Illinois. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like there will be a spring edition of Ray Walsh’s Classicon. Currently, William Patrick Maynard and I are writing about the programming that will be featured at PulpFest 2019. We’ll be posting about the panels and presentations through June 10. On June 17, we’ll write about this year’s author signings, something new we’re planning for the convention. Check things out at www.pulpfest.com. Laurie Powers biography of LOVE STORY MAGAZINE editor Daisy Bacon is currently scheduled for release around the end of 2019. I will be carrying this book. It’s entitled QUEEN OF THE PULPS. Please reserve your copy today. Recently, I was contacted about carrying the Armchair Fiction line of books. I’ve contacted the publisher and will certainly be able to stock their books. Founded in 2011, they are dedicated to the restoration of classic genre fiction. Their forté is early science fiction, but they also publish mystery, horror, and westerns. They have a strong line of lost race novels. Their books are illustrated with art from the pulps and such. -

Extraterrestrial Places in the Cthulhu Mythos

Extraterrestrial places in the Cthulhu Mythos 1.1 Abbith A planet that revolves around seven stars beyond Xoth. It is inhabited by metallic brains, wise with the ultimate se- crets of the universe. According to Friedrich von Junzt’s Unaussprechlichen Kulten, Nyarlathotep dwells or is im- prisoned on this world (though other legends differ in this regard). 1.2 Aldebaran Aldebaran is the star of the Great Old One Hastur. 1.3 Algol Double star mentioned by H.P. Lovecraft as sidereal The double star Algol. This infrared imagery comes from the place of a demonic shining entity made of light.[1] The CHARA array. same star is also described in other Mythos stories as a planetary system host (See Ymar). The following fictional celestial bodies figure promi- nently in the Cthulhu Mythos stories of H. P. Lovecraft and other writers. Many of these astronomical bodies 1.4 Arcturus have parallels in the real universe, but are often renamed in the mythos and given fictitious characteristics. In ad- Arcturus is the star from which came Zhar and his “twin” dition to the celestial places created by Lovecraft, the Lloigor. Also Nyogtha is related to this star. mythos draws from a number of other sources, includ- ing the works of August Derleth, Ramsey Campbell, Lin Carter, Brian Lumley, and Clark Ashton Smith. 2 B Overview: 2.1 Bel-Yarnak • Name. The name of the celestial body appears first. See Yarnak. • Description. A brief description follows. • References. Lastly, the stories in which the celes- 3 C tial body makes a significant appearance or other- wise receives important mention appear below the description. -

Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction

Andrew May Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction Editorial Board Mark Alpert Philip Ball Gregory Benford Michael Brotherton Victor Callaghan Amnon H Eden Nick Kanas Geoffrey Landis Rudi Rucker Dirk Schulze-Makuch Ru€diger Vaas Ulrich Walter Stephen Webb Science and Fiction – A Springer Series This collection of entertaining and thought-provoking books will appeal equally to science buffs, scientists and science-fiction fans. It was born out of the recognition that scientific discovery and the creation of plausible fictional scenarios are often two sides of the same coin. Each relies on an understanding of the way the world works, coupled with the imaginative ability to invent new or alternative explanations—and even other worlds. Authored by practicing scientists as well as writers of hard science fiction, these books explore and exploit the borderlands between accepted science and its fictional counterpart. Uncovering mutual influences, promoting fruitful interaction, narrating and analyzing fictional scenarios, together they serve as a reaction vessel for inspired new ideas in science, technology, and beyond. Whether fiction, fact, or forever undecidable: the Springer Series “Science and Fiction” intends to go where no one has gone before! Its largely non-technical books take several different approaches. Journey with their authors as they • Indulge in science speculation—describing intriguing, plausible yet unproven ideas; • Exploit science fiction for educational purposes and as a means of promoting critical thinking; • Explore the interplay of science and science fiction—throughout the history of the genre and looking ahead; • Delve into related topics including, but not limited to: science as a creative process, the limits of science, interplay of literature and knowledge; • Tell fictional short stories built around well-defined scientific ideas, with a supplement summarizing the science underlying the plot. -

![The Nemedian Chroniclers #21 [SS16]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9335/the-nemedian-chroniclers-21-ss16-1079335.webp)

The Nemedian Chroniclers #21 [SS16]

REHeapa Summer Solstice 2016 By Lee A. Breakiron LET THERE BE UPDATES The Howard Collector Glenn Lord published 18 issues of his ground-breaking REH fanzine between 1961 and 1973, which we reviewed before. [1] He put out a 19th number (Vol. 4, #1) in summer, 2011, in the same 5 ½ x 8 ¾ format with light gray textured softcovers and 52 pages for $20.00. The volume contains the original version of “Black Canaan” (first published in 2010 by the Robert E. Howard Foundation), an untitled verse, an untitled Breckinridge Elkins fragment, and a drawing, all by Howard from Lord’s collection. Critic Fred Blosser contributes reviews of Steve Harrison’s Casebook and Tales of Weird Menace, both edited by REHupan Rob Roehm and published in 2011 by the Foundation, as well as El Borak and Other Desert Adventures (2010) and Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures (2011), both edited by REHupan Rusty Burke and published by Del Rey. Blosser observes that the detective-type stories in the first two books tend to be better the more REH concentrates on action and weirdness rather than sleuthing. Blosser thinks highly of the last two, but wishes that Burke had not corrected Howard’s French spellings. THC #19 won Lord the 2012 Robert E. Howard Foundation (“Aquilonian”) Award for Outstanding Periodical. [2] A projected 20th issue, to include the original version of “Crowd-Horror,” was never published (“Crowd- Horror” would be published in 2013 in The Collected Boxing Fiction of Robert E. Howard: Fists of Iron), since Lord died of a heart attack December 31, 2011 at age 80. -

Universidade Federal De Santa Catarina Pós

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS/INGLÊS E LITERATURA CORRESPONDENTE WEIRD FICTION AND THE UNHOLY GLEE OF H. P. LOVECRAFT KÉZIA L’ENGLE DE FIGUEIREDO HEYE Dissertação Submetida à Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina em cumprimento dos requisitos para obtenção do grau de MESTRE EM LETRAS Florianópolis Fevereiro, 2003 My heart gave a sudden leap of unholy glee, and pounded against my ribs with demoniacal force as if to free itself from the confining walls of my frail frame. H. P. Lovecraft Acknowledgments: The elaboration of this thesis would not have been possible without the support and collaboration of my supervisor, Dra. Anelise Reich Courseil and the patience of my family and friends, who stood by me in the process of writing and revising the text. I am grateful to CAPES for the scholarship received. ABSTRACT WEIRD FICTION AND THE UNHOLY GLEE OF H. P. LOVECRAFT KÉZIA L’ENGLE DE FIGUEIREDO HEYE UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA 2003 Supervisor: Dra. Anelise Reich Corseuil The objective of this thesis is to verify if the concept of weird fiction can be classified not only as a sub-genre of the horror literary genre, but if it constitutes a genre of its own. Along this study, I briefly present the theoretical background on genre theory, the horror genre, weird fiction, and a review of criticism on Lovecraft’s works. I also expose Lovecraft’s letters and ideas, expecting to show the working behind his aesthetic theory on weird fiction. The theoretical framework used in this thesis reflects some of the most relevant theories on genre study. -

HP Lovecraft

H.P. LOVECRAFT TUTTI I RACCONTI 1931-1936 (1992) a cura di Giuseppe Lippi Indice Nota alla presente edizione Introduzione Cronologia di Howard Phillips Lovecraft Fortuna di Lovecraft Lovecraft in Italia RACCONTI (1931-1936) Le montagne della follia (1931) La maschera di Innsmouth (1931) La casa delle streghe (1932) La cosa sulla soglia (1933) Il prete malvagio (1933) Il libro (1933) L'ombra calata dal tempo (1935) L'abitatore del buio (1935) RACCONTI SCRITTI IN COLLABORAZIONE REVISIONI (1931-1936) La trappola (con Henry S. Whitehead, 1931) L'uomo di pietra (con Hazel Heald, 1932) L'orrore nel museo (con Hazel Heald, 1932) Attraverso le porte della Chiave d'Argento (con E. Hoffmann Price, 1932/1933) La morte alata (con Hazel Heald, 1933) Dall'abisso del tempo (con Hazel Heald, 1933) L'orrore nel camposanto (con Hazel Heald, 1933/1935) L'albero sulla collina (con Duane W. Rimel, 1934) Il "match" di fine secolo (con R.H. Barlow, 1934) "Finché tutti i mari..." (con R.H. Barlow, 1935) L'esumazione (con Duane W. Rimel, 1935) Universi che si scontrano (con R. H. Barlow, 1935) Il diario di Alonzo Typer (con William Lumley, 1935) Nel labirinto di Eryx (con Kenneth Sterling, 1936) L'oceano di notte (con R.H. Barlow, 1936) APPENDICE Due racconti giovanili: Rimembranze del Dr. Samuel Johnson (1917) La dolce Ermengarda, ovvero: Il cuore di una ragazza di campagna Una round-robin-story: Sfida dall'ignoto, di Catherine L. Moore, Abraham Merritt, H.P. Love- craft, Robert E. Howard, Frank Belknap Long (1935) APPENDICI BIBLIOGRAFICHE Riferimenti bibliografici dei racconti contenuti nel presente volume Bibliografia generale Nota alla presente edizione Questo libro è per Fabio Calabrese, Claudio De Nardi, Francesco Fac- canoni, Giancarlo Pellegrin, Gianni Ursini e tutta la redazione triestina del "Re in Giallo". -

By Lee A. Breakiron REVIEWING the REVIEW

REHEAPA Summer Solstice 2010 By Lee A. Breakiron REVIEWING THE REVIEW Belying its name, the first issue of the fanzine The Howard Review (THR) contained no reviews, but only because its editor and publisher, Dennis McHaney, had wanted to hold it to 24 pages while including Howard’s story “The Fearsome Touch of Death” and Glenn Lord’s “The Fiction of Robert E. Howard: A Checklist.” McHaney had sent a list of the published works to Lord, who added the unpublished works. “Fearsome” had not been reprinted since its appearance in Weird Tales in February, 1930, and it was de rigueur at the time for any REH fanzine to feature some unpublished or unreprinted material by Howard. Lord had provided the material and permission required, as he was to do for so many fanzines, magazines, and books published during the Howard Boom of the 1970s. In the issue’s editorial, McHaney states that his zine “will be strictly devoted to Robert E. Howard, and will only review new material by others if that material is directly related to R.E.H., or one of his creations,” including pastiches. It would also “contain fiction and poetry by Howard, including obscure, out-of-print items as well as unpublished pieces.” [1, p. 3] And so began one of the better known fanzines of the period, produced by the longest active contributor to Howard fandom, given that he is still active. Marked by continual experimentation and improvement in format and style, THR reflected its creator’s interest and skill in graphic design and his drive to constantly hone those skills and utilize the best technology available. -

Krishna Excerpts

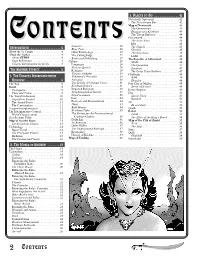

3. PLACES TO GO . 41 Novorecife Spaceport . 42 The Nova Iorque Bar . 42 Map of Novorecife . 43 The Gymnasium . 43 Disguise as a Krishnan . 43 The Terran Embassy . 44 ONTENTS Gozashtand . 44 CCONTENTS The Novo News . 44 Rœz . 45 Couriers . 26 INTRODUCTION . 4 The Hamda . 45 Bijar Post . 26 Hershíd . 45 About the de Camps . 4 Other Technology . 27 The Gavehona . 45 About the Author . 4 The Cutting Edge . 27 Lusht . 46 About GURPS . 4 Books and Publishing . 27 The Republic of Mikardand . 46 Page References . 4 Culture . 28 Mishé . 46 Viagens Interplanetarias Series . 5 Languages . 28 The Qararuma . 47 Flowery Speech . 28 THE KRISHNA STORIES . 5 Zinjaban . 47 Religions . 29 The Great Train Robbery . 47 Varasto Alphabet . 29 Chilihagh . 48 1. THE VIAGENS INTERPLANETARIAS Nehavend’s Proverbs . 29 Bákh . 48 UNIVERSE . 8 Astrology . 30 Dhaukia . 48 The War . 9 The Temple of Ultimate Verity . 31 Free City of Majbur . 49 Brazil . 9 Krishnan Science . 31 Street Addresses . 49 Portuguese . 9 Imported Religions . 32 Katai-Jhogorai . 50 Pluto and Triton . 9 Neophilosophical Society . 32 Dur . 51 The World Federation . 10 Neo-Puritanism . 32 Savoir-Faire . 51 Population Control . 10 Law . 34 Baianch . 51 The Armed Force . 11 Festivals and Entertainment . 34 Zir . 52 The Constabulary . 11 Duels . 34 Zá and Zesh . 52 Viagens Interplanetarias . 12 Bath-Houses . 34 Qaath . 53 The Interplanetary Council . 12 Krishnan Titles . 35 Balhib . 53 World Classifications . 12 The Society for the Preservation of Zanid . 54 Star Systems Table . 13 Krishnan Culture . 35 The Affair of the King’s Beard . 54 Map of Nearby Stars . 13 Daily Life . -

Back Numbers 11 Part 1

In This Issue: Columns: Revealed At Last........................................................................... 2-3 Pulp Sources.....................................................................................3 Mailing Comments....................................................................29-31 Recently Read/Recently Acquired............................................32-39 The Men Who Made The Argosy ROCURED Samuel Cahan ................................................................................17 Charles M. Warren..........................................................................17 Hugh Pentecost..............................................................................17 P Robert Carse..................................................................................17 Gordon MacCreagh........................................................................17 Richard Wormser ...........................................................................17 Donald Barr Chidsey......................................................................17 95404 CA, Santa Rosa, Chandler Whipple ..........................................................................17 Louis C. Goldsmith.........................................................................18 1130 Fourth Street, #116 1130 Fourth Street, ASILY Allan R. Bosworth..........................................................................18 M. R. Montgomery........................................................................18 John Myers Myers ..........................................................................18