The Role of the Colombo Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GP Text Paste Up.3

FACING ASIA A History of the Colombo Plan FACING ASIA A History of the Colombo Plan Daniel Oakman Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/facing_asia _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry Author: Oakman, Daniel. Title: Facing Asia : a history of the Colombo Plan / Daniel Oakman. ISBN: 9781921666926 (pbk.) 9781921666933 (eBook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Economic assistance--Southeast Asia--History. Economic assistance--Political aspects--Southeast Asia. Economic assistance--Social aspects--Southeast Asia. Dewey Number: 338.910959 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Emily Brissenden Cover: Lionel Lindsay (1874–1961) was commissioned to produce this bookplate for pasting in the front of books donated under the Colombo Plan. Sir Lionel Lindsay, Bookplate from the Australian people under the Colombo Plan, nla.pic-an11035313, National Library of Australia Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press First edition © 2004 Pandanus Books For Robyn and Colin Acknowledgements Thank you: family, friends and colleagues. I undertook much of the work towards this book as a Visiting Fellow with the Division of Pacific and Asian History in the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University. There I benefited from the support of the Division and, in particular, Hank Nelson and Donald Denoon. -

Document Resume Ed 052 069 So 000 900 Title

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 052 069 SO 000 900 TITLE [Catalogues of Third Country Training Resources in East, Near East, and South Asia. Volumes 1and 2.] INSTITUTION Agency for International Development (Dept. of State), Washington, D.C. Office of International Training. PUB DATE Feb 71 NOTE 451p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$16.45 DESCRIPTORS Agricultural Education, Catalogs, Community Development, Course Descriptions, *Developing Nations, Developmental Programs, Educational Programs, Health Occupations Education, *International Programs, Manpower Development, Program Descriptions, *Teacher Education, *Technical Education, Trade and Industrial Education, *Vocational Education IDENTIFIERS *Asia ABSTRACT Both of these catalogs are part of a series of four official AID publications covering both academic and non-academic training opportunities. These two in particular were developed to encourage increased use by Asians of the regional training resources designed to assist them in the economic and social development of their countries. The catalogues are intended for use as a working tool by both American and host government training officers and technical advisors in determining where to train participants, when to train, and to provide information about technical programs, fees, prerequisites, resource addresses, housing, language of instruction, and the United States involvement with the training resource. There are programs described for: 1) agriculture, 2) industry and mining, 3) transportation, 4) labor, 5)health and sanitation, 6)education, 7) public safety and administration, 8) community development, and 9) communications media. India, Lebanon, Pakistan, Turkey, Iran, Greece, U.A.R. (one) ,and Afghanistan (one) are included along with Thailand, Philippines, Korea, China, and Japan (one).(Author/AWW) catalo ue U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE,OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG INATING IT. -

Sceye PDF-File

copy no.^ IITPiSRATIGiiAL LABOUR OFFICE IliEIA BKAIJCH Industrial cad Labour Devol oprante in. August 1953a E»BB-Each Gooftioa of tliis Boport ray bo taken out separately» Coatonto. Pages» CHAPTER 1» IHTIS1HATIOHAI» LABOUR QBGAHIFAIIOfl. 11. Po lit io al Situation and Acnisdotrativo Action; I. L 0. RaGiSTRY-GENEVA (a) Resignation of Finenoo Minister accoptod; 13 SEP 1956 Prise Uinioter takes ever Finance Portfolio. 1 (b) Lori: of Tripartito Machinery for labour in tho ’*?■" (f States; Fovicrz in Indian Labour Casotto. 2-5 fwiih : (o) Incoro: ITenr Cabinet f oread. 7 on : 12. Activities of Esternai Services;. 8 CHAPTER 2. IHTtlSIATIOHAL AIO) RATIONAL OftJAHJSAYIOUS. 25. Wgo-Sarnors* Organisations ; (a) Verified Eehborohip of AU-X^dio Organisations of Workers; Statonoefc in. PcTlianant. 9-10 (b) S0vonth Annual Session of Xndian Rational Cement /Workers’"Federation; Approval of negotiations for long^iQixi SottlOEont with Employers» 11-13 (e) Madras: Recognition of Single Union for each Industry: Legislation to bo introduced. 14 CHAPTER 5. EOQnOjfEC QSESTIGHS.- 32. Publio Finanoo aod Fiscal Policy; Fiftoon States Float Slow Loans; Amount totals 640 Million Supoos. 15 54. Leonard.c Pltaming.Control and SevolopEont; (a) World Bank’s Views on Second Five-Year Plans ’’Sonorhat too taabitious“. 16-19 (b) First Atonic Roactor goes into Operation; Peaceful uco of Energy assured. 20 (o) Fivo Por Coat of Jute Loons to bo eoaled; Stop to curb Production dun to Huge Stocks cad Jute Scarcity. 21 -H- Contante Pares. SG* WG£QDS (a) Ajmer: Draft Proposals fixing Kiairam Ratos of Wages for Etaploycont in Printing Frans Eotcblishnoufci» 22 (b) Trcvancoro-Ooeliin; Mininun. -

The BRICS Model of South-South Cooperation

August 2017 UJCI AFRICA-CHINA POLICY BRIEF 2 The BRICS Model of South-South Cooperation Swaran Singh UJCI Africa-China Policy Brief No 2 The BRICS Model of South-South Coperation Swaran Singh Professor in the School of International Studies of Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India. Series Editor: Dr David Monyae Published in August 2017 by: The University of Johannesburg Confucius Institute 9 Molesey Avenue, Auckland Park Johannesburg, South Africa www.confucius-institute.joburg External language editor: Riaan de Villiers Designed and produced by Acumen Publishing Solutions For enquiries, contact: Hellen Adogo, Research Assistant, UJCI Tel +27 (01)11 559-7504 Email: [email protected] Disclaimer: The views expressed in this Policy Brief do not necessarily reflect those of the UJCI. All rights reserved. This publication may not be stored, copied or reproduced without the permission of the UJCI. Brief extracts may be quoted, provided the source is fully acknowledged. UJCI Africa-China Brief No 2 | August 2017 THE earliest imaginations of South-South cooperation (SSC) have been traced to the Afro-Asian anti-colonial struggles of the 1940s. This is when initial ideas about shared identity, building solidarity towards asserting sovereignty, and channeling simmering opposition to the imperial ‘North’ first germinated. The Asian Relations Conference held in New Delhi in 1947, followed by the Afro-Asian Conference at Bandung (Indonesia) in April 1955, marked the first watersheds in the evolution of SSC, supported by the ‘non-alignment’ and ‘Third World’ paradigms (Chen and Chen 2010: 108-109). In 1960, the SSC thesis was further developed by the dependency theories of neo-Marxist sociologists from South America, who underlined the subservient nature of trade relations between their region and North America (Copeland 2009:64). -

Myth and Misrepresentation in Australian Foreign Policy Menzies and Engagement with Asia

BenvenutiMyth and Misrepresentation and Jones in Australian Foreign Policy Myth and Misrepresentation in Australian Foreign Policy Menzies and Engagement with Asia ✣ Andrea Benvenuti and David Martin Jones In 1960 the deputy leader of the Australian Labor Party, Gough Whitlam, declared that Australia “has for ten years missed the opportunity to interpret the new nations to the old world and the old world to the new na- tions.”1 Throughout the 1960s, Labor spokesmen attacked the foreign policy of Sir Robert Menzies’s Liberal–Country Party coalition government (1949– 1966) for both its dependence on powerful friends and its alleged insensitivity to Asian countries.2 This criticism of Liberal foreign policy not only persisted in later decades but also became the prevailing academic and media ortho- doxy.3 As we show here, Labor’s criticism constitutes the basis of a tenacious political myth that demands critical reevaluation. Menzies’s political opponents and, subsequently, his academic critics have claimed that his attitude toward Asia was permeated by suspicion and conde- scension. From the 1970s, an inchoate Labor left and academic understand- ing contended that conservative Anglo-centrism “had placed Australia on the losing side of almost every external engagement from the Suez Crisis to Viet- nam.”4 A decade later, analysts writing in the context of the Labor-driven doc- trine of “enmeshment” with Asia reinforced this emerging foreign policy or- 1. Gordon Greenwood and Norman Harper, eds., Australia in World Affairs 1956–1960 (Melbourne: Cheshire, 1963), p. 96. 2. See, for instance, Mads Clausen, “‘Falsiªed by History’: Menzies, Asia and Post-Imperial Australia,” History Compass, Vol. -

519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190

GIRLS-2019/10/15 1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION GIRLS’ EDUCATION RESEARCH AND POLICY SYMPOSIUM: LEARNING ACROSS A LIFETIME Washington, D.C. Tuesday, October 15, 2019 Opening Remarks and Panel: MODERATOR: CHRISTINA KWAUK Fellow, Center for Universal Education The Brookings Institution BHAGYASHRI DENGLE Regional Director, Asia Plan International HUGO GORST-WILLIAMS Team Leader, Girls’ Education UK DFID ROBERT JENKINS Chief, Education Associate Director, Programme Division, UNICEF LEANNA MARR Director, Office of Education USAID MARTHA MUHWEZI Executive Director, FAWE Africa Intervening Early: Bringing Gender Into Early Childhood Education: MODERATOR: DANA SCHMIDT Senior Program Officer Echidna Giving PRESENTER: SAMYUKTA SUBRAMANIAN 2019 Echidna Global Scholar The Brookings Institution VRINDA DATTA Director of the Centre for Early Childhood Education Development Ambedkar University, Delhi ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 600 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 GIRLS-2019/10/15 2 SUMAN SACHDEVA 2015 Echidna Global Scholar The Brookings Institution Empowerment at Adolescence: STEM Skills for Girls’ Leadership and Innovation: MODERATOR: SARAH GAMMAGE Director of Gender, Economic Empowerment, and Livelihoods ICRW NASRIN SIDDIQA 2019 Echidna Global Scholar The Brookings Institution MALIHA KHAN Chief Programs Officer Malala Fund MEIGHAN STONE Senior Fellow, Women and Foreign Policy Program Council on Foreign Relations Entering Adulthood: Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) and Girls’ Transitions -

Report 183: Report of the Committee Visit to India and Indonesia

PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Report 183: Report of the Committee Visit to India and Indonesia 2 - 10 August 2018 Joint Standing Committee on Treaties © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 ISBN 978-1-74366-901-3 (Printed Version) ISBN 978-1-74366-902-0 (HTML Version) This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. Contents Delegation members ......................................................................................................................... v The Report 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 Aims and objectives .............................................................................................................. 1 Outcomes ................................................................................................................................ 2 India ............................................................................................................................ 2 Indonesia .................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................. 3 2 Delhi.......................................................................................................................... -

The Value of International Students to Cultural Diversity in Regional Australia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Southern Queensland ePrints THE VALUE OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS TO CULTURAL DIVERSITY IN REGIONAL AUSTRALIA Dr Delroy Brown Multicultural Centre University of Southern Queensland INTRODUCTION This paper argues that the presence of international students with the potential to promote cultural diversity and ensure sustainability in market share to universities is not being valued and explored in regional Australia. While some recognition is given to the economic benefits of the international student phenomenon to Australia, there is a reluctance to promote community engagement, which will not only enhance cultural diversity in regional Australia, but will also satisfy the personal and professional goals of visiting students, and ensure sustainability in market share for regional universities. The paper discusses community engagement as a mechanism that creates value to enhance cultural diversity with direct and indirect benefits for visiting students, local communities and universities as key stakeholders. Under the Colombo Plan which granted scholarships as aid to developing nations between 1950 and 1985, overseas students were valued for their contribution to promoting cultural diversity and the development of lasting friendships with local Australians (Cameron 2010; Lane 2009). By contrast today, many international students express dissatisfaction with the lack of contact they currently experience with locals (Marginson 2012b), and they perceive themselves as valued only for their money (Trounson 2012a). The over commercialisation of the international education sector plus its recent rapid growth and succeeding decline in student traffic and revenue from 2006 to 2011, have prompted calls for a new paradigm to meet the Asian Century (Marginson 2012a) and a recognition of “the huge significance of the flow of young people, knowledge, experience and values” (Zegeras, 2012, p.23). -

Turning Back the Direction of Canadian Foreign Aid

Turning back the direction of Canadian Foreign Aid Masimba Muzamhindo Advisor: Matthew McLennan Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the [Masters of Arts in Public Ethics] School of Ethics, Social Justice and Public Service Saint Paul University / Université Saint-Paul © Masimba Muzamhindo, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 Chapter One—Introduction…………………………………………………………………………….1 Main Currents of Academic Debate………………………………………………………...14 The Relative Strength of Macdonald’s Approach…………………………………………20 Areas To Be Analyzed……………………………………………………………………….24 Summary and Structure of Thesis………………………………………………………….30 Chapter Two--- What is Foreign Aid?……………………………………………………………….31 Chapter Three - Canada’s History of Foreign Aid……………………………………………….….43 Chapter Four -- Where Canadian Foreign Aid is at Now………………..…………………………..64 Chapter Five --- Why Canadian Foreign Aid doesn’t Achieve its Stated Goals………………… 70 Chapter Six ------ A New Canadian Aid Program: The Capability Approach……………………..78 Chapter Seven--- Conclusions………………………………………………………………………..109 ii Chapter One: Introduction The purpose of this thesis is to target a perceived lack of consistent success within Canadian foreign aid policy and recommend a way forward. It is also the aim of this thesis to provide an ethical and practical guideline to Canadian foreign aid policy through the Capability Approach. This Approach will be further fleshed out as this thesis runs its course. At the end of 2009 Canadian aid was cut from 0.45 per cent to 0.25 per cent of Canada’s gross national income (GNI). (Brown 79) This signalled the end of the optimism that Canada had had about aid at the end of the Cold War. There was the belief that aid could be used for projects that could target poverty rather than for geopolitics. -

Colombo Plan – from India's Initiative on Foreign

PRACE NAUKOWE UNIWERSYTETU EKONOMICZNEGO WE WROCŁAWIU RESEARCH PAPERS OF WROCŁAW UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS nr 294 ● 2013 Economical and Political Interrelations in the Asia-Pacific Region ISSN 1899-3192 Marcin Nowik Wrocław University of Economics COLOMBO PLAN – FROM INDIA’S INITIATIVE ON FOREIGN ASSISTANCE TO REGIONAL ORGANISATION IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC* Abstract: The paper presents the evolution of the Colombo Plan from Cold War aid provision framework into a vital, regional, inter-governmental organisation in Asia and the Pacific region. The Colombo Plan, originally a commonwealth initiative, with a crucial role of India at its inception, has lost its meaning with the socio-economic development of Asian member states, progress of economic integration in the region and withdrawal of major Western donors. The reform conducted by Japan and Korea in mid-1990s allowed for finding a new niche for the Plan, changed the character of the organisation from North-South into South- South relations. Today, the institution is providing a framework for policy discussion, it offers knowledge exchange and networks Asian youth. New accessions to the organisation prove its attractive character in the political and economic scene in Asia-Pacific. Keywords: Colombo Plan, India, Asia, assistance. 1. Introduction In the post-war period, after a successful implementation of European Recovery Programme, so called Marshall Plan, there was a general consensus on significant benefits for economic development of large-scale, macro-planned, foreign assistance activities. Economic progress was perceived as an inevitable factor for political stability and capitalist path of development, thus would allow to save developing countries from falling into communist regimes. -

Annexure B MAJOR DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION INITIATIVES IN

Annexure B MAJOR DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION INITIATIVES IN COUNTRIES ABROAD (1) Bhutan Government of India has been extending development cooperation assistance to Bhutan’s Five Year Plans. GoI committed financial support of INR 4500 Crore for the 11th Five Year Plan of Bhutan (2013-2018). This included INR 2800 Cr Project Tied Assistance, INR 850 Cr Programme Grant and INR 850 Cr towards Small Development Projects/High Impact Community Development Programme (SDPs/HICDPs). GoI also committed financial support of INR 4500 Crore for the 12th Five Year Plan of Bhutan (2018-2023). This includes INR 2800 Cr Project Tied Assistance, INR 850 Cr Programme Grant and INR 850 Cr towards Small Development Projects. In addition, we also extended financial support in term of Loan and Grant for ongoing Hydro Electric Projects viz. Punatsangchhu- I, Punatsangchhu- II, Mangdechhu and Kholongchhu. (2) Nepal India has robust developmental cooperation with Nepal, under which a number of connectivity, physical and social infrastructure projects have been completed, and several others are under various stages of implementation. Projects completed in recent years include petroleum products pipeline, power transmission lines, Emergency and Trauma Centre, Integrated Check Post at Birgunj and Biratnagar, Pashupati Dharmashala, and a number of road stretches within Nepal. A series of cross-border connectivity and other infrastructure projects such as rail links, roads, Integrated Check Posts, Nepal Police Academy, polytechnic, etc. are under implementation. The Government also extends assistance annually to the High Impact Community Development Projects (formerly Small Development Projects) programme in Nepal for the implementation of projects each costing less than NPR 5 crore (INR 3.125 crore approx.). -

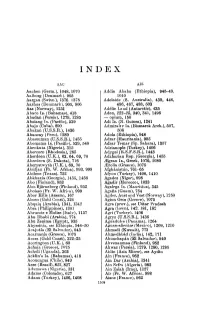

Aachen (Germ.)

INDEX A.AO .A.IS Aachen (Germ.), 1048, 1070 Addis Ababa (Ethiopia), 945-49, Aalborg (Denmarl<). 905 1010 Aargau (Switz.), 1376. 1378 Adelaide (S. Australia), 439, 446, Aarhus (Denmark), 905, 906 486, 487, 488, 503 Aas (Norway), 1251 Adelie LAnd (Antarctic), 435 Abaco Is. (BahamaR), 418 Aden, 222-25, 340, 341, 1496 Abadan (Persia), 1279, 1285 -opium, 150 Abaiang Is. (Pacific), 539 Adi Is. (N. Guinea), 1241 Ahajo (Cuba), 890 Admiral tv Is. (Bismarck Arch.), 507, Abakan (U.S.S.R.), 1436 508 Abancay (Peru), 1289 Adola (Ethiopia), 948 Abastuman (U.S.S.R.), 1455 Adrar (Mauritania), 995 Abemama Is. (Pacifi<o), 539, 540 Adrar Temar (Flp. Sahara), 1357 Abt'okuta (Nigeria), 315 Adrianople (Turkey), 1406 Abercorn (Rhodesia), 285 Adygei ( R.S.F.S.R.), 1443 Aberdeen (U.K.), 63, 64, 69, 70 Adzharian Rep. (Georgia), 1455 Aberdeen (S. Dakota), 716 .tEgean Is., Greek, 1076, 1080 Aberystwyth (U.K.), 69, 70 .tEtolia (Greet•e), 1075 Abidjan (Fr. W. Africa), 993, 999 Afghanistan, 761-65 Abilene (Texas), 722 Afyon (Turkey), 1406, 1410 Abkhazia (Georgi&), 1455, 1456 Agadez (Niger), 998 Abo (Finland), 953 Agadir (Morocco), 1033 Abo.Bjorneborg (Finland), 952 AgalPga Is. (!11.auritius), 345 Ahoisso (Fr. W. Afri .. a), 999 Agnil.a (Guam), 754 Abor Hills (Assam), 167 AgdAr, Austand Vest (Norway),l250 Aboso (Gold Const), 324 Agion Oros (Greet"e), 1075 Abqaiq (Arabia), 1341, 1342 Agra (prov.), see Uttar Pradesh A bra (Philippines), 1301 Agra (town), 142. 181, 182 Abruzzie e Molise (lta.ly), 1157 Agri (1'nrke:v). 1406 Abu Dhabi (Arabia), 774 Agryz (U.S.S.R.), 1436 Abu Zenima (Egypt), 935 Aguadul<·e (Panama), 1264 Ahyssinia, Hee Ethiopia, 944-50 A~ruaR<•aliAnteR (ME!xiro), 1209, 1210 A~ajutla (El Salvador), 943 Ahmadi (Kuwait), 773 Act~rnania (Greece), 1075 Ahm .