February 17, 2021 Hon. Sarah Carroll, Chair NYC Landmarks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Together by Selma Burke Looking Questions: Find the Sculpture, Together, on Display on the Old Former Prison Wall in the Rear Sculpture Garden at the Michener

Together by Selma Burke Looking Questions: Find the sculpture, Together, on display on the old former prison wall in the rear sculpture garden at the Michener. • Write down 10 words that come to your mind in response to Burke’s sculpture. They can be words that describe the artwork or your feelings/reactions to it. • One of Burke’s favorite themes to use in her artwork was family, love and unity. How has she shown this in her artwork? What other symbols could represent this theme? • Are there any personal connections can you Selma Burke, Together, 1975; cast 2001, make with Burke’s artwork? Explain your bronze, H. 74 x W. 49 x D. 9 inches, James A. Michener Art Museum. Museum purchase with answer. assistance from John Horton, William Mandel, the Bjorn T. Polfelt memorial fund, Carolyn Cal- kins Smith and the Friends of Selma Burke. • How do you define family? If you could create a sculpture about your family, what would it look like? Describe it to a friend or classmate. About the Artwork: The Michener Art Museum commissioned the casting of the relief sculpture Together from the resin mold used to produce Selma Burke’s original 1975 bronze bas-relief, owned by Hill House Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The work, which depicts a male and female figure holding an infant between their bodies, focuses on family love and unity, a theme found in many of Burke’s works. Learn more about Burke by visiting the Michener’s online Bucks County Artists’ Database at https://bucksco.michenerartmuseum.org. -

Checklist of Artworks

Checklist of Artworks: Cat.# Artist Title Lender 1 Unknown Coverlet LACMA 2 Day, Thomas Sampler Chest North Carolina Museum of History 3 Unknown Carved Box Top George E. Jordan 4 Dave the Potter Bulbous Jar with Two Ear Lug Handles Prof. Franklin Fenenga 5 Unknown Jug in the Form of a Human Head Prof. Franklin Fenenga 6 Unknown Slave Mask New Orleans Museum of Art 7 Unknown Weathervane Mrs. Terry Dintenfass 8 Unknown Butter Patter with Black Man’s Head Prof. and Mrs. David C. Driskell 9 Unknown Basket from Melrose Plantation George E. Jordan 10 Unknown Carved Hand Stick Prof. and Mrs. David C. Driskell 11 Unknown Flute from North Carolina Prof. and Mrs. David C. Driskell 12 Moss, Leo Thelma Myla Levy Perkins 13 Moss, Leo Mina Myla Levy Perkins 14 Johnson, James Butler Jewelry Box Mr. and Mrs. Joseph L. Pierce 15 Unknown Walking Cane Dr. and Mrs. William Bascom 16 Johnston, Joshua The McCormick Family The Maryland Historical Society 17 Johnston, Joshua Portrait of Mrs. Barbara Baker Murphy C.R. Babe 18 Johnston, Joshua Portrait of Captain John Murphy C.R. Babe 19 Johnston, Joshua Young Lady on a Red Sofa Mr. and Mrs. Peter H. Tillou 20 Johnston, Joshua Girl in Garden Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C. 21 Audubon, John James Virginian Partridge Mr. and Mrs. Sidney F. Brody 22 Lion, Jules Portrait of John J. Audubon Louisiana State Museum 23 Hudson, Julian Self Portrait Louisiana State Museum 24 Reason, Patrick Kneeling Slave Dr. Dorothy B. Porter 25 Duncanson, Robert S. Uncle Tom and Little Eva Detroit Institute of Arts 26 Duncanson, Robert S. -

ARTISTS MAKE US WHO WE ARE the ANNUAL REPORT of the PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY of the FINE ARTS Fiscal Year 2012-13 1 PRESIDENT’S LETTER

ARTISTS MAKE US WHO WE ARE THE ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF THE FINE ARTS FISCAL YEAR 2012-13 1 PRESIDENT’S LETTER PAFA’s new tagline boldly declares, “We Make Artists.” This is an intentionally provocative statement. One might readily retort, “Aren’t artists born to their calling?” Or, “Don’t artists become artists through a combination of hard work and innate talent?” Well, of course they do. At the same time, PAFA is distinctive among the many art schools across the United States in that we focus on training fine artists, rather than designers. Most art schools today focus on this latter, more apparently utilitarian career training. PAFA still believes passionately in the value of art for art’s sake, art for beauty, art for political expression, art for the betterment of humanity, art as a defin- ing voice in American and world civilization. The students we attract from around the globe benefit from this passion, focus, and expertise, and our Annual Student Exhibition celebrates and affirms their determination to be artists. PAFA is a Museum as well as a School of Fine Arts. So, you may ask, how does the Museum participate in “making artists?” Through its thoughtful selection of artists for exhibition and acquisition, PAFA’s Museum helps to interpret, evaluate, and elevate artists for more attention and acclaim. Reputation is an important part of an artist’s place in the ecosystem of the art world, and PAFA helps to reinforce and build the careers of artists, emerging and established, through its activities. PAFA’s Museum and School also cultivate the creativity of young artists. -

Comparing Sculptures of the Italian Renaissance and the Harlem Renaissance

www.high.org/david Grade 5 Barbara Kirberger Lee Street Elementary School Clayton County, Georgia Comparing Sculptures of the Italian Renaissance and the Harlem Renaissance Georgia QCC: FAVA: 5.3−5.6, 5.8, 5.10−5.12, 5.14, 5.15, 5.17, 5.19 (Grade 5) Multiple Intelligence: Spatial, Logical, and Interpersonal Character Education: Perseverance, Creativity, and Citizenship Bloom’s Taxonomy: Recall→list, identify name; Application→construct, translate; Analysis→compare, investigate; Synthesis→create, design; Evaluate→decide, assess Sculpture: works of Verrocchio, Richmond Barthé, Selma Burke, and Augusta Savage Goal ♦ Students will understand the meaning of Renaissance. ♦ Students will compare and contrast Verrocchio’s life and sculptures of the Italian Renaissance to a Harlem Renaissance sculptor and his or her work. ♦ Students will build a sculpture with foil and Pariscraft. Objective ♦ Students will research historical events and use this knowledge as a source of ideas for artwork. ♦ Students will compare and contrast artwork of the same type produced by different artists. ♦ Students will construct a sculpture using simple materials in a similar technique as that of Verrocchio or a Harlem Renaissance artist. Materials ♦ Handouts biographies of artists, graphic organizers, and pencils. ♦ Slides or pictures of key artworks produced by the artists. ♦ Renaissance CD and 1920’s Jazz CD. ♦ Aluminum foil, Plastercraft, scissors, water, cardboard, wood bases, hammer, nails, and wire. Verrocchio’s David Restored: A Renaissance Bronze from the National Museum of the Bargello, Florence November 18, 2003 – February 8, 2004 www.high.org/david Preparation Show slides or pictures of selected sculptures and have a short discussion about them. -

Black Women in the Visual Arts: a Comparative Study Lois Jones Peirre-Noel

New Directions Volume 3 | Issue 2 Article 6 4-1-1976 Black Women in the Visual Arts: A Comparative Study Lois Jones Peirre-Noel Follow this and additional works at: http://dh.howard.edu/newdirections Recommended Citation Peirre-Noel, Lois Jones (1976) "Black Women in the Visual Arts: A Comparative Study," New Directions: Vol. 3: Iss. 2, Article 6. Available at: http://dh.howard.edu/newdirections/vol3/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Directions by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Peirre-Noel: Black Women in the Visual Arts: A Comparative Study NATIONAl Black Women In the Visual Arts "Forever Free," by Edmonia Lewis 12 A Comparative Study By Lois Jones Pierre-Noel The strength and position of the Black woman artist has existed as an important contribution from the early history of Black American artists. Women artists emerged from a most discouraging beginning in this country to attain remarkable achieve- ments. For to be both "Black" and "wom- an" was to express one's creativity in "frustrating obscurity." Then, too, art history books failed to mention Black women artists before the middle of the 19th Century. From the mid-1800s to the 20th Cen- tury, the more significant contr.ibutions of Black women artists were made by those who traveled abroad for the recognition the American society was not willing to give. Outstanding in this group was Edmonia Lewis, one of the most vibrant personalities of her time.Born in New York in 1845, Lewis became the first Black woman sculptor. -

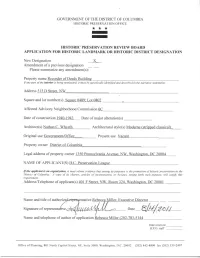

Recorder of Deeds Building

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking “x” in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter “N/A” for “not applicable.” For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Recorder of Deeds Building other names 2. Location street & number 515 D Street NW not for publication city or town Washington, DC vicinity state DC code DC County code 001 zip code 20001 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally statewide locally. ( See continuation sheet for additional comments). -

Louis Licitra-PRESIDENT Born: Syracuse, New York Education: SUNY Delhi, Syracuse University & Rockefeller University Resident of Bucks County for Over 30 Years

Louis Licitra-PRESIDENT Born: Syracuse, New York Education: SUNY Delhi, Syracuse University & Rockefeller University Resident of Bucks County for over 30 years. Worked with FACT for over 15 years Additionally on the local Bucks County event planning board for Broadway Cares/EFA Previous positions include President of the New Hope Chamber of Commerce and board member for over 7 years; event planning board for The Rainbow Room LGBTQA youth group; event planning board for New Hope Celebrates PRIDE (local LGBT organization); Additional support and volunteer work with The New Hope Community Association for high school youth job placement; New Hope Arts member; New Hope Historical Society member; and fund-raising/promotion/volunteer assistance for various organizations throughout the year. Currently, co-owner of Rainbow Assurance, Inc., Title Insurance Agency offering title insurance for PA & NJ. Herb Andrus-VICE PRESIDENT Born: Philadelphia Education: University of Pennsylvania & Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY Certifications: Education and Intervention Facilitator (CDC certified.) Worked at Family Sevice Association of Bucks County as Facilitator Lifetime resident of Bucks County Volunteered at --William Way Community Center FACT Board for 3 yrs Boyd Oliver-TREASURER Born: McKeesport PA Graduated Grove City College (PA) with degree in accounting Retired CPA with major public accounting, Fortune 500 corporate and small business experience spanning over 30 years. Has owned and operated his own retail/internet businesses. When not traveling around the globe with his partner, he still enjoys the occasional special consulting assignment or project. Member: AICPA (American Institute Of CPA's) Resident of New Hope/Solebury, Bucks County for over 20 years Tim Philpot-SECRETARY On the board of FACT for two years and served as secretary for the past year. -

Shiny Sculptures- Mixed Media Assemblages Grade Level: Pre-Kindergarten

1 Shiny Sculptures- Mixed Media Assemblages Grade Level: Pre-Kindergarten LESSON OVERVIEW Summary Students will learn about the work of Augusta Savage and use her art as inspiration for their own. Unit: Special Exhibitions, Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman Lesson: This project introduces students to artist Augusta Savage. Savage was a female sculptor who worked during the Harlem Renaissance and advocated for the rights of African American artists. In this project students will learn about the importance of Augusta Savage within a historical context and use this information as inspiration when creating their own work of art. Students will explore a variety of materials and techniques to create a metallic sculpture. STANDARDS Creative Arts Art: PK.CA.1. Experiment with a variety of media and art materials for tactile experience and exploration. PK.CA.2 Create artistic works with intent and purpose using varying tools, texture, color, and technique. PK.CA.3 Present and respond to visual art created by self and others. OBJECTIVE Students can learn about the artist Augusta Savage and her historical importance. Students can distinguish between 2-D and 3-D works of art. Students can explore a variety of materials to create a sculpture. ASSESSMENT/EVALUATION Students show evidence of proficiency through a variety of assessments. Aligned with the Lesson Objective Formative/Summative Performance-Based/Rubric Formal/Informal Students will successfully answer prompts and questions given by instructor Students will explore a variety of materials to create a 3-D work of art MATERIALS Look! Look! Look! at Sculpture by Nancy Elizabeth Wallace Metallic Pipe Cleaners Metallic Pony Beads Washers Various metallic objects 2 Foam Blocks Visual examples of historical artwork for reference ACTIVATING STRATEGY What materials can artists use to create sculpture? INSTRUCTION Students will learn about Augusta Savage and her importance in the Harlem Renaissance and as a mentor to many internationally known artists. -

Selma Hortense Burke Was Born on December 31, 1900, in Mooresville, North Carolina to a Local AME Church Minister, Neal Burke, and Mary Jackson Burke

Debra DeBerry Clerk of Superior Court DeKalb County Selma(December Hortense 31, 1900 – August 29, 1995Burke ) "American Sculptor” Selma Hortense Burke was born on December 31, 1900, in Mooresville, North Carolina to a local AME Church minister, Neal Burke, and Mary Jackson Burke. Selma was the seventh of ten children and attended a one-room segregated schoolhouse. Her love of sculpture started at a very young age where she molded clay found on the riverbanks, nearby. While her mother insisted she focus on a formal education, her grandmother, a painter, encouraged her to pursue her artistic expression. In 1924, Selma graduated from the St. Agnes School for Nurses at Winston-Salem University. She began working as a nurse and in 1928, she married her childhood friend, Durant Woodward. Unfortunately, Woodward died less than a year later of blood poisoning. After moving to New York in 1935, she worked as a private nurse for the dowager heiress of the Otis Elevator Company in Cooperstown. It was during this time that she met Jamaican writer and poet, Claude McKay and was introduced to the transformative energy of the Harlem Renaissance. The volatile relationship with McKay was short-lived as he often destroyed Selma’s sculptures if they didn’t meet his standards. Selma began to teach for the Harlem Community Arts Center under the leadership of celebrated African-American sculptress, Augusta Savage. Around the same time, she worked for the Works Progress Selma Burke with her portrait bust of Administration on the New Deal Federal Art Project and sculpted a bust of Booker T. -

Curriculum Vitae

Kelvin Parnell Jr. Curriculum Vitae University of Virginia 82 Barclay Pl Ct, Apt D McIntire Department of Art Charlottesville, VA P.O. Box 400130 [email protected] Charlottesville, VA 22904 Tel: 724.579.2338 EDUCATION 2016— University of Virginia Ph.D. Candidate, Art and Architectural History Dissertation (In Progress): “Casting Bronze, Recasting Race: Sculpture in Mid-to-Late Nineteenth-Century America” Advisor: Dr. Carmenita Higginbotham Graduate Certificate in American Studies (completed 2019) 2012—2016 Duquesne University of the Holy Spirit B.A., Art History and History, Cum Laude RESEARCH INTEREST I am interested in representations of race and national identity in nineteenth- and twentieth-century American painting, sculpture, and print. I use critical race theory and aesthetics to inform my work. PUBLICATIONS 2020 “Amy Sherald (1973 - ),” In the Grove Dictionary of Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020). (Forthcoming) 2020 “Nicolino Calyo (1799 - 1884),” In the Grove Dictionary of Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020). (Forthcoming) 2020 “Richard (Howard) Hunt” In the Grove Dictionary of Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020). (Forthcoming) 2020 “Julie Mehretu (1970 - ),” In the Grove Dictionary of Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020). (Forthcoming) 2020 “African American Art. II. Abstract Sculpture,” In the Grove Dictionary of Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020). (Forthcoming) 2020 “Presidential Patronage: Franklin D. Roosevelt and Selma Burke’s Four Freedoms.” In Journal of American Studies, 2020. (Delayed due to COVID- 19) 2018 “Absence and Presence: Contesting Urban Aboriginality.” In Beyond Dreamings: The Rise of Indigenous Australian Art in the U.S. Charlottesville: Kluge- Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection, 2018. CV (Parnell) 1 INVITED TALKS, CONFERENCES, AND SYMPOSIA 2020 “Casting Bronze, Recasting Race: Sculpture in Mid-to-Late Nineteenth-Century America,” Association of Historians of American Art Fellows Talk, October 14, 2020. -

1/30/79 Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 1/30/79; Container 105 to Se

1/30/79 Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 1/30/79; Container 105 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf .... .. .. 'l'HE PRESIDENT'S SCHEDULE· .,! ·f ·! Tuesday January 30, 1979 j t; 7:30 Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski. - 'l'he Oval Office. 8:15 Mr. Frank Moore The Oval Office. 9:00 Meeting with His Excellency Deng Xiaoping, (2 hrs.) Vice Premier of the State council of the People's Republic of China. (Dr. Zb'igniew Brzezinski). '!'he Cabinet Room. 11:30 Mr. Jody Powell The Oval Office. I ! ' 1:30 ICC Chairman Dan O'Neal. (Mr. Stuart E.izenstat). (10 min.) The Oval Office. 2:00 Mr.· James Mcintyre The Oval Office.• (:20 min.) 2:30 Greet Recipients of the First Annual l'lomen' s (10 min.) Caucus for Art Outstanding Achievement in the Visual Arts .Awards. (Ms. Bess Abell) The Oval Office •. \' THE WHITE HOUSE WASHI!'lGTON 1/30/79 F'rank Moore. I Cong. Correspondence The attached letters were returned in·the President's outbox today and are-forwarded to you for delivery. Rick Hutcheson cc: Stu Eizenstat ,' THE WHITE HOUSE WASH I NGTO•N January 30, 1979 MEMORANDUM FOR THE PRESIDENT FROM: STU EIZENSTAT SUBJECT:: Responses to letters from 1) Frank Fitzsimmons and 2) Congressman Jim Howard 1. Letter from Frank Fitzsimmons. Frank Fitzsimmons of the Teamsters Union has written to you opposing recent decisions made by the· ICC, and asking you' to request the resignation of ICC Chairman Dan O'Neal. Fred Kahn, Bob Strauss, Landon Butler, and I recommend that you send the attached reply letter. -

Augusta Savage Host Committee Community Partners Ameris Bank Mr

SPONSORS Exhibition Season Presenters Augusta Savage Host Committee Community Partners Ameris Bank Mr. and Mrs. Thompson Baker, III Avant Arts City of Jacksonville Sally F. Baldwin City of Green Cove Springs Cultural Council of Greater Caroline O. Brinton GENERATION W Jacksonville, Inc. Susan and Hugh Greene Jacksonville Public Library Robert D. and Isabelle T. Davis Peter and Kiki Karpen Jax Chamber Endowment at The Community John and Nancy Kennedy Foundation for Northeast Florida Mr. and Mrs. William Harrell Leadership Jacksonville The Director’s Circle at John and Jan Hirabayashi Museum of Science & History the Cummer Museum Mr. Hank Holbrook and OneJax The Schultz Family Endowment Mrs. Pam D. Paul Ritz Theatre and Museum Sharón Simmons and Shirley Webb Special Project Partners Sponsors Velma Monteiro-Tribble TEDxJacksonville Charmaine T.W. Chiu and Rick and Amy Morales Ernest Y. Koe University of North Florida Center Kitty and Phil Phillips of Urban Education and Policy Dr. Elizabeth Colledge James Richardson and Cynthia G. Edelman Family Fund Sandra Hull-Richardson University of North Florida Department of Art and Design The Hicks Foundation Dr. and Mrs. H. Warner Webb Women of Color Cultural Bob and Monica Jacoby The Law Office of James F. Waters, III, P.A. Foundation Dick and Marty Jones Nina and Lex Waters Women’s Giving Alliance Trisha Meili and Jim Schwarz Mr. and Mrs. Charles B. Zimmerman Michael Munz In-Kind Sponsors NEA Art Works Augusta Savage Exhibition Agility Press, Inc. Van and Sandra Royal Planning and Community Advisory Committee DoubleTree Jacksonville Riverfront Mr. Ryan A. Schwartz Carol Alexander The Schomburg Center for Allan Schwartzman Dustin Harewood Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library Carl S.