Afro-Art: a Learning Packet Ruth Eleanor Osborn Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizens Coinage Advisory Committee

Citizens Coinage Advisory Committee Public Meeting Monday, April 19, 2013, 9:30 AM United State Mint Headquarters 801 9th Street NW, 2nd Floor Conference Room Washington, D.C. In attendance: Erik Jansen Gary Marks (Chair) Michael Moran Michael Olson Michael Ross Donald Scarinci Jeanne Stevens-Sollman Thomas Uram Heidi Wastweet 1. Chairperson Marks called the meeting to order at 9:12 A.M. 2. The letters and minutes of the March 11, 2012 meeting were unanimously approved. 3. April Stafford of the United States Mint presented the candidate reverse designs for the 2014 Presidential $1 Coin Program. 4. After each member had commented on the candidate designs, Committee members rated proposed designs by assigning 0, 1, 2, or 3 points to each, with higher points reflecting more favorable evaluations. With nine (9) members voting, the maximum possible point total was twenty-seven (27). The committee’s scores for the 2014 Presidential $1 Coin Program: Warren G. Harding Obverse: WH-01: 0 WH-02: 1 WH-03: 15 WH-04: 0 WH-05: 0 WH-06: 4 WH-07: 21 (Recommended design) Calvin Coolidge Obverse: CC-01: 0 CC-02: 0 CC-03: 6 CC-04: 8 CC-05: 0 CC-06: 19 (Recommended design) Herbert Hoover Obverse: HH-01: 12 HH-02: 5 HH-03: 2 HH-04: 0 HH-05: 17 (Recommended design) HH-06: 3 HH-07: 2 Franklin Delano Roosevelt Obverse: FDR-01: 17 (Recommended design) FDR-02: 11 FDR-03: 0 FDR-04: 0 FDR-05: 0 FDR-06: 10 FDR-07: 1 FDR-08: 0 5. -

Betye Saar – Art Icon Award Waco Theater Center, Wearable Art Gala - 2019

BETYE SAAR – ART ICON AWARD WACO THEATER CENTER, WEARABLE ART GALA - 2019 On Saturday, June 1, 2019, artist Betye Saar will receive the Art Icon Award at WACO Theater Center’s Wearable Art Gala in Los Angeles. As one of the artists who ushered in the development of Assemblage art, Betye Saar’s practice reflects on African American identity, spirituality and the connectedness between different cultures. Her symbolically rich body of work has evolved over time to succinctly reflect the environmental, cultural, political, racial, technological, economic, and historical context in which it exists. Saar was born Betye Irene Brown on July 30, 1926 to Jefferson Maze Brown and Beatrice Lillian Parson in Los Angeles, California. Both parents attended the University of California, Los Angeles, where they met. After her father's death in 1931, Saar and her mother, brother, and sister moved in with her paternal grandmother, Irene Hannah Maze in the Watts neighborhood in Los Angeles. As a child, Saar witnessed Simon Rhodia’s construction of the Watts Towers in Los Angeles, which introduced ideas of creating art from found objects to embody both the spiritual and the technological. This early influence, combined with her interest in metaphysics, magic, and the occult formed the basis of Saar’s early assemblage work. With assemblages such as the iconic The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972), Saar sought to reveal marginalized and hidden histories. Her work has examined social invisibility of black Americans in service jobs, colorism, and the ways objects can retain memories and histories of their owners. Saar’s work can be found in the permanent collections of more than 60 museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and LACMA, among others. -

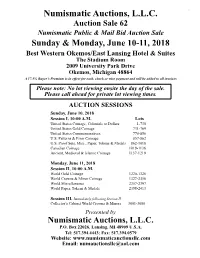

Numismatic Auctions, L.L.C. P.O

NumismaticNumismatic Auctions, LLC Auctions, Auction Sale 62 - June 10-11, 2018 L.L.C. Auction Sale 62 Numismatic Public & Mail Bid Auction Sale Sunday & Monday, June 10-11, 2018 Best Western Okemos/East Lansing Hotel & Suites The Stadium Room 2009 University Park Drive Okemos, Michigan 48864 A 17.5% Buyer’s Premium is in effect for cash, check or wire payment and will be added to all invoices Please note: No lot viewing onsite the day of the sale. Please call ahead for private lot viewing times. AUCTION SESSIONS Sunday, June 10, 2018 Session I, 10:00 A.M. Lots United States Coinage , Colonials to Dollars 1-730 United States Gold Coinage 731-769 United States Commemoratives 770-856 U.S. Patterns & Error Coinage 857-862 U.S. Proof Sets, Misc., Paper, Tokens & Medals 862-1018 Canadian Coinage 1019-1136 Ancient, Medieval & Islamic Coinage 1137-1219 Monday, June 11, 2018 Session II, 10:00 A.M. World Gold Coinage 1220-1326 World Crowns & Minor Coinage 1327-2356 World Miscellaneous 2357-2397 World Paper, Tokens & Medals 2398-2413 Session III, Immediately following Session II Collector’s Cabinet World Crowns & Minors 3001-3080 Presented by Numismatic Auctions, L.L.C. P.O. Box 22026, Lansing, MI 48909 U.S.A. Tel: 517.394.4443; Fax: 517.394.0579 Website: www.numismaticauctionsllc.com Email: [email protected] Numismatic Auctions, LLC Auction Sale 62 - June 10-11, 2018 Numismatic Auctions, L.L.C. Mailing Address: Tel: 517.394.4443; Fax: 517.394.0579 P.O. Box 22026 Email: [email protected] Lansing, MI 48909 U.S.A. -

It's Not Enough to Say 'Black Ls Beautiful' I

I : t .: t I t I I I : I 1. : By F,ank Bowling It's Not Enough to Say 'Black ls Beautiful' I I I I 1 I I I 1 AIvin Loving: Diana: Tine iip,2, 197'1.20 feet.8 inches wide: Ziede( galle(y. The probleils oi how to iudge black ari by black artists are nol made not with the works themselves or their deiivery. Not with a positrvely easier by simply installing it; herE a painler examines the works arriculared object or set of objects. It is as though what is being said is of Williams, Loving, Edwerds, Johnson and Whitten as both esthetic that whatever-black people do in the varloLLs areas labeied art ls obiecls and as symbols etpressing a unique heritago and stale of mif,d Art-hence Black Art. And various spoKesmen nake ruies to govern this supposed new form oi erpressron. Unless we accept the absurdi- ty ol such stereolypes as "they 1'e all got rhythm---." and even if we Recent New York arl has brought about curious and oiten be.rilder- do, can we stretch a little fuilher to Jay they've all got paintrng'i ing confronrations which tend to stress the potitical over the esthetic. Whichever way this question is atrswered there are orhers oi more A considerubie amount oi wnting, geared away irom hlstory, iaste immediale importance, such as: Whal precisely is lile nature ol biack and questiotrs oI quality in traditiotral esihetic terms, dnfts tcwards art'i If we reply, however, tongue-in-cheek. -

Silhouetted Stereotypes in the Art of Kara Walker

standards. They must give up their personal desires and Walker insists that her work “mimics the past, but it’s all live for the common good of the community. Hester about the present” (Tang 161). After her earning her strays from this conformity the first time when she has B.F.A. at Atlanta College of Art and further study at the sexual relations with her minister, a major violation of Rhode Island School of Design, Walker rose to community standards. She not only defiled herself, but prominence by winning the MacArthur Genius Grant in she defiled the leader of the community, and therefore, 1997 at the young age of 27 (Richardson 50). This the entire community. She does not conform again when prominent award poised Walker for great she bears the scarlet letter A with pride and dignity. The accomplishments, yet also exposed her to harsh community’s intention for punishing Hester is to force criticism from fellow African American women artists, her to fully repent. Hester seems to go through the such as Betye Saar, who launched a critical letterwriting motions of repentance. She stands on the scaffold, she campaign to boycott Walker’s work (Wall 277). Walker’s wears the letter A, and she lives on the outskirts of town. critics are quick to demonize aspects of her personal However, Hester’s “haughtiness,” “pride,” and “strong, life, like her marriage to a white European man, and calm, steadfastly enduring spirit” undermines the even her mental state, accusing her of mental distress community’s objective (Hawthorne, 213). -

Alison Saar Foison and Fallow

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 2010 Media Contact: Elizabeth East Telephone: 310-822-4955 Email: [email protected] Alison Saar Foison and Fallow 15 September through 30 October 2010 Opening reception for the artist: Wednesday 15 September, 6-8 p.m. Venice, CA –- L.A. Louver is pleased to announce an exhibition of new three-dimensional mixed media works on paper and sculpture by Alison Saar. In this new work Saar explores the cycle of birth, maturation, death and regeneration through the changing season and her own experience of aging. The two drawings Foison, 2010 and Fallow, 2010, which also give their titles to the exhibition, derive from Saar’s recent fascination with early anatomy illustration. As Saar has stated “The artists of the time seemed compelled to breathe life back into the cadavers, depicting them dancing with their entrails, their skin draped over their arm like a cloak, or fe- tuses blooming from their mother’s womb.” In these drawings, Saar has replaced the innards of the fi gures with incongruous elements, to create a small diorama: Foison, 2010 depicts ripe, fruitful cotton balls and their nemesis the cotton moth, in caterpillar, chrysalis and mature moth stage; while Fallow, 2010 portrays a fallow fawn fetus entwined in brambles. In creating these works Saar references and reexamines her early work Alison Saar that often featured fi gures with “cabinets’ in their chest containing relics Fallow, 2010 mixed media of their life. 55 1/2 x 29 x 1 in. (141 x 73.7 x 2.5 cm) My work has always dealt with dualities -- usually of the wild, feral side in battle with the civil self -----Alison Saar One of two sculptures in the exhibition, En Pointe, 2010 depicts a fi gure hanging by her feet and sprouting massive bronze antlers. -

Chapter 18: Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1933-1939

Roosevelt and the New Deal 1933–1939 Why It Matters Unlike Herbert Hoover, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was willing to employ deficit spending and greater federal regulation to revive the depressed economy. In response to his requests, Congress passed a host of new programs. Millions of people received relief to alleviate their suffering, but the New Deal did not really end the Depression. It did, however, permanently expand the federal government’s role in providing basic security for citizens. The Impact Today Certain New Deal legislation still carries great importance in American social policy. • The Social Security Act still provides retirement benefits, aid to needy groups, and unemployment and disability insurance. • The National Labor Relations Act still protects the right of workers to unionize. • Safeguards were instituted to help prevent another devastating stock market crash. • The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation still protects bank deposits. The American Republic Since 1877 Video The Chapter 18 video, “Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal,” describes the personal and political challenges Franklin Roosevelt faced as president. 1928 1931 • Franklin Delano • The Empire State Building 1933 Roosevelt elected opens for business • Gold standard abandoned governor of New York • Federal Emergency Relief 1929 Act and Agricultural • Great Depression begins Adjustment Act passed ▲ ▲ Hoover F. Roosevelt ▲ 1929–1933 ▲ 1933–1945 1928 1931 1934 ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ 1930 1931 • Germany’s Nazi Party wins • German unemployment 1933 1928 107 seats in Reichstag reaches 5.6 million • Adolf Hitler appointed • Alexander Fleming German chancellor • Surrealist artist Salvador discovers penicillin Dali paints Persistence • Japan withdraws from of Memory League of Nations 550 In this Ben Shahn mural detail, New Deal planners (at right) design the town of Jersey Homesteads as a home for impoverished immigrants. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Art for People's Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965

Art/African American studies Art for People’s Sake for People’s Art REBECCA ZORACH In the 1960s and early 1970s, Chicago witnessed a remarkable flourishing Art for of visual arts associated with the Black Arts Movement. From the painting of murals as a way to reclaim public space and the establishment of inde- pendent community art centers to the work of the AFRICOBRA collective People’s Sake: and Black filmmakers, artists on Chicago’s South and West Sides built a vision of art as service to the people. In Art for People’s Sake Rebecca Zor- ach traces the little-told story of the visual arts of the Black Arts Movement Artists and in Chicago, showing how artistic innovations responded to decades of rac- ist urban planning that left Black neighborhoods sites of economic depres- sion, infrastructural decay, and violence. Working with community leaders, Community in children, activists, gang members, and everyday people, artists developed a way of using art to help empower and represent themselves. Showcas- REBECCA ZORACH Black Chicago, ing the depth and sophistication of the visual arts in Chicago at this time, Zorach demonstrates the crucial role of aesthetics and artistic practice in the mobilization of Black radical politics during the Black Power era. 1965–1975 “ Rebecca Zorach has written a breathtaking book. The confluence of the cultural and political production generated through the Black Arts Move- ment in Chicago is often overshadowed by the artistic largesse of the Amer- ican coasts. No longer. Zorach brings to life the gorgeous dialectic of the street and the artist forged in the crucible of Black Chicago. -

Art-Related Archival Materials in the Chicago Area

ART-RELATED ARCHIVAL MATERIALS IN THE CHICAGO AREA Betty Blum Archives of American Art American Art-Portrait Gallery Building Smithsonian Institution 8th and G Streets, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20560 1991 TRUSTEES Chairman Emeritus Richard A. Manoogian Mrs. Otto L. Spaeth Mrs. Meyer P. Potamkin Mrs. Richard Roob President Mrs. John N. Rosekrans, Jr. Richard J. Schwartz Alan E. Schwartz A. Alfred Taubman Vice-Presidents John Wilmerding Mrs. Keith S. Wellin R. Frederick Woolworth Mrs. Robert F. Shapiro Max N. Berry HONORARY TRUSTEES Dr. Irving R. Burton Treasurer Howard W. Lipman Mrs. Abbott K. Schlain Russell Lynes Mrs. William L. Richards Secretary to the Board Mrs. Dana M. Raymond FOUNDING TRUSTEES Lawrence A. Fleischman honorary Officers Edgar P. Richardson (deceased) Mrs. Francis de Marneffe Mrs. Edsel B. Ford (deceased) Miss Julienne M. Michel EX-OFFICIO TRUSTEES Members Robert McCormick Adams Tom L. Freudenheim Charles Blitzer Marc J. Pachter Eli Broad Gerald E. Buck ARCHIVES STAFF Ms. Gabriella de Ferrari Gilbert S. Edelson Richard J. Wattenmaker, Director Mrs. Ahmet M. Ertegun Susan Hamilton, Deputy Director Mrs. Arthur A. Feder James B. Byers, Assistant Director for Miles Q. Fiterman Archival Programs Mrs. Daniel Fraad Elizabeth S. Kirwin, Southeast Regional Mrs. Eugenio Garza Laguera Collector Hugh Halff, Jr. Arthur J. Breton, Curator of Manuscripts John K. Howat Judith E. Throm, Reference Archivist Dr. Helen Jessup Robert F. Brown, New England Regional Mrs. Dwight M. Kendall Center Gilbert H. Kinney Judith A. Gustafson, Midwest -

A Finding Aid to the Charles Henry Alston Papers, 1924-1980, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Charles Henry Alston Papers, 1924-1980, in the Archives of American Art Jayna M. Hanson Funding for the digitization of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art August 2008 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Biographical Information, 1924-1977........................................................ 5 Series 2: Correspondence, 1931-1977.................................................................... 6 Series 3: Commission and Teaching Files, 1947-1976........................................... -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI fihns the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in ^ e w rite r free, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Infonnation Company 300 North Zed) Road, Ann Aibor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 THE INFUSION OF AFRICAN AMERICAN ART FROM EIGHTEEN-EIGHTY TO THE EARLY NINETEEN-NINETIES FOR MIDDLE AND HIGH SCHOOL ART EDUCATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ronald Wayne Claxton, B.S., M.A.E.