Representation in Art and Film: Identity and Stereotype

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Betye Saar – Art Icon Award Waco Theater Center, Wearable Art Gala - 2019

BETYE SAAR – ART ICON AWARD WACO THEATER CENTER, WEARABLE ART GALA - 2019 On Saturday, June 1, 2019, artist Betye Saar will receive the Art Icon Award at WACO Theater Center’s Wearable Art Gala in Los Angeles. As one of the artists who ushered in the development of Assemblage art, Betye Saar’s practice reflects on African American identity, spirituality and the connectedness between different cultures. Her symbolically rich body of work has evolved over time to succinctly reflect the environmental, cultural, political, racial, technological, economic, and historical context in which it exists. Saar was born Betye Irene Brown on July 30, 1926 to Jefferson Maze Brown and Beatrice Lillian Parson in Los Angeles, California. Both parents attended the University of California, Los Angeles, where they met. After her father's death in 1931, Saar and her mother, brother, and sister moved in with her paternal grandmother, Irene Hannah Maze in the Watts neighborhood in Los Angeles. As a child, Saar witnessed Simon Rhodia’s construction of the Watts Towers in Los Angeles, which introduced ideas of creating art from found objects to embody both the spiritual and the technological. This early influence, combined with her interest in metaphysics, magic, and the occult formed the basis of Saar’s early assemblage work. With assemblages such as the iconic The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972), Saar sought to reveal marginalized and hidden histories. Her work has examined social invisibility of black Americans in service jobs, colorism, and the ways objects can retain memories and histories of their owners. Saar’s work can be found in the permanent collections of more than 60 museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and LACMA, among others. -

Silhouetted Stereotypes in the Art of Kara Walker

standards. They must give up their personal desires and Walker insists that her work “mimics the past, but it’s all live for the common good of the community. Hester about the present” (Tang 161). After her earning her strays from this conformity the first time when she has B.F.A. at Atlanta College of Art and further study at the sexual relations with her minister, a major violation of Rhode Island School of Design, Walker rose to community standards. She not only defiled herself, but prominence by winning the MacArthur Genius Grant in she defiled the leader of the community, and therefore, 1997 at the young age of 27 (Richardson 50). This the entire community. She does not conform again when prominent award poised Walker for great she bears the scarlet letter A with pride and dignity. The accomplishments, yet also exposed her to harsh community’s intention for punishing Hester is to force criticism from fellow African American women artists, her to fully repent. Hester seems to go through the such as Betye Saar, who launched a critical letterwriting motions of repentance. She stands on the scaffold, she campaign to boycott Walker’s work (Wall 277). Walker’s wears the letter A, and she lives on the outskirts of town. critics are quick to demonize aspects of her personal However, Hester’s “haughtiness,” “pride,” and “strong, life, like her marriage to a white European man, and calm, steadfastly enduring spirit” undermines the even her mental state, accusing her of mental distress community’s objective (Hawthorne, 213). -

Alison Saar Foison and Fallow

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 2010 Media Contact: Elizabeth East Telephone: 310-822-4955 Email: [email protected] Alison Saar Foison and Fallow 15 September through 30 October 2010 Opening reception for the artist: Wednesday 15 September, 6-8 p.m. Venice, CA –- L.A. Louver is pleased to announce an exhibition of new three-dimensional mixed media works on paper and sculpture by Alison Saar. In this new work Saar explores the cycle of birth, maturation, death and regeneration through the changing season and her own experience of aging. The two drawings Foison, 2010 and Fallow, 2010, which also give their titles to the exhibition, derive from Saar’s recent fascination with early anatomy illustration. As Saar has stated “The artists of the time seemed compelled to breathe life back into the cadavers, depicting them dancing with their entrails, their skin draped over their arm like a cloak, or fe- tuses blooming from their mother’s womb.” In these drawings, Saar has replaced the innards of the fi gures with incongruous elements, to create a small diorama: Foison, 2010 depicts ripe, fruitful cotton balls and their nemesis the cotton moth, in caterpillar, chrysalis and mature moth stage; while Fallow, 2010 portrays a fallow fawn fetus entwined in brambles. In creating these works Saar references and reexamines her early work Alison Saar that often featured fi gures with “cabinets’ in their chest containing relics Fallow, 2010 mixed media of their life. 55 1/2 x 29 x 1 in. (141 x 73.7 x 2.5 cm) My work has always dealt with dualities -- usually of the wild, feral side in battle with the civil self -----Alison Saar One of two sculptures in the exhibition, En Pointe, 2010 depicts a fi gure hanging by her feet and sprouting massive bronze antlers. -

Betye Saar: Uneasy Dancer” in Milan from 15 September 2016 to 8 January 2017

FONDAZIONE PRADA PRESENTS THE EXHIBITION “BETYE SAAR: UNEASY DANCER” IN MILAN FROM 15 SEPTEMBER 2016 TO 8 JANUARY 2017 Milan, 14 September 2016 – Fondazione Prada presents the exhibition “Uneasy Dancer”, a comprehensive survey of work by Betye Saar (Los Angeles, 1926). This exhibition, hosted at the Nord Gallery, opens to the public from 15 September 2016 through 8 January 2017. Curated by Elvira Dyangani Ose, “Betye Saar: Uneasy Dancer” is the first exhibition of the American artist in Italy, and brings together over 80 works including installations, assemblages, collages and sculptures produced between 1966 and 2016. “Uneasy Dancer” is an expression Betye Saar has used to define both herself and her artistic practice. In her own words, “my work moves in a creative spiral with the concepts of passage, crossroads, death and rebirth, along with the underlying elements of race and gender.” This process implies “a stream of consciousness” that explores the ritualized mysticism present in recovering personal stories and iconographies from everyday objects and images. Several key elements lie at the center of her artistic practice: an interest in the metaphysical, the representation of feminine memory, and African-American identity which, in her work, takes on takes on evocative and unusual forms. As Saar has said about her work, “It was really about evolution rather than revolution, about evolving the consciousness in another way and seeing black people as human beings instead of the caricatures or the derogatory images.” Betye Saar’s earliest artistic memory was stimulated by the Towers of Simon Rodia in Watts, a suburb of Los Angeles she frequented with her Grandmother in the 1930’s. -

You've Come a Long Way, Baby

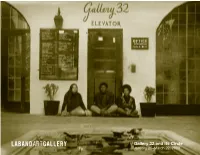

Gloria Bohanon Born 1939, Atlanta BS, Wayne State University, Detroit, 1962 MA, Wayne State University, Detroit, 1968 Died 2008, Los Angeles Bohanon taught painting, printmaking and design at Los Angeles City College for thirty years and served as one of the first members on the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Black Arts Council. Solo or two-person presentations of her work were held at Brockman Gallery, Los Angeles (1970 and 1971) and Gallery 32, Los Angeles (1970; with Suzanne Jackson). Bohanon’s work was included in the survey exhibitions Gallery 32 & Its Circle, Laband Gallery, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles (2009); An Exhibition of Black Women Artists, University Center Art Gallery, University of California, Santa Barbara (1975); Black Mirror, Womanspace, Los Angeles (1973); Los Angeles 1972: A Panorama of Black Artists, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (1972); California Black Craftsmen, Mills College Art Gallery, Oakland (1970); and The Black Art Show, Pasadena City College (1970). Suzanne Jackson Born 1944, St. Louis BFA, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, 1966 MFA, Yale University School of Drama, New Haven, 1990 Jackson lives and works in Savannah, Georgia. From 1969–1970 she ran Gallery 32 from her live/ work studio at 672 South Lafayette Park Place in Los Angeles. Recent solo and survey exhibitions include Off the Wall, Mnuchin Gallery, New York (2021); Suzanne Jackson: News!, Ortuzar Projects, New York (2019); Suzanne Jackson: Five Decades, Jepson Center/Telfair Museums, Savannah (2019); holding on to a sound, O-Town House, Los Angeles (2019); Life Model: Charles White and His Students, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2019); West by Midwest, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (2018–19); Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, Brooklyn Museum, New York and the M. -

Kara Walker Steel Stillman

Art in America May, 2011 In the Studio: Kara Walker Steel Stillman KARA WALKER'S RISE to the top of the art world came fast and loaded with controversy. At the age of 24, three months after the artist received an MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), her work was included in a 1994 survey exhibition at New York 's The Drawing Center, wowing critics and viewers alike. Over the next three years, she had eight one-person shows and became the youngest artist ever to win a MacArthur "genius" award. She also came under attack by a group of 200 older black artists, led by Betye Saar, who mounted a vigorous letter-writing campaign seeking to prevent the exhibition of her work, on the grounds, as artist Howardena Pindell later put it, that its representations of black people constituted "visual terrorism." So singular and strong was Walker's first publicly exhibited work- muralsized, wall- mounted tableaux of black cut-paper silhouettes depicting caricatures of antebellum slaves and slaveholders in scenes of sex, violence and dissolution- that it might well have eclipsed all that followed. But Walker had other tricks up her sleeve. Since the late '90s, while continuing the cut-paper series, she has developed significant bodies of work in other mediums, notably drawing, writing and filmmaking, that have deepened her multiform recasting of tales of African-American life. Walker has been drawing since childhood-her father, Larry, is an artist and retired professor of art who moved the family from Stockton, Calif., where Walker was born in 1969, to the suburbs of Atlanta, in 1983, to direct the art department at Georgia State University. -

Gallery 32 and Its Circle

Gallery 32 and Its Circle January 25–March 22, 2009 “Gallery 32 offered a space where people could express an independent voice in their Gallery 32 and Its Circle and Its Circle Carolyn Peter and Damon Willick work and not be labeled. Gallery 32 was never a black In late 1968 a very young Suzanne Jackson address the aesthetic and political issues that gallery, a women’s gallery, opened an art gallery west of downtown Los concerned them. As a result, it often became Angeles in unit number 32 of the Granada a site for artistic innovation and community or a men’s gallery; it was a Building, at 672 North Lafayette Park Place. activism. While it closed after only two years, January 25–March 22, 2008 gallery about artists who came She called it Gallery 32 in homage to Alfred the history of Gallery 32 offers a glimpse into Laband Art Gallery, Loyola Marymount University through with something to Stieglitz’s Gallery 291 from earlier in the century. the vibrancy of the Los Angeles art scene of Bob Heliton, Timothy Washington in front of Rather than bringing European modernism to say.” —SUZANNE JACKSON Gallery 32 and Its Circle was curated by Carolyn Peter, director and curator of the Laband Art the period. Gallery 32, 1969, gelatin silver print, Courtesy of the New York audiences, as Stieglitz did, Jackson Gallery, and Damon Willick, assistant professor of modern and contemporary art history, Bob Heliton Archive. Loyola Marymount University. introduced the work of young, relatively Suzanne Jackson opened Gallery 32 while unknown L.A. -

Hammer Museum Fall 2011 Non Profit Org

Hammer Museum Fall 2011 Non Profit Org. US Postage 10899 Wilshire Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90024 USA Fall 2011 Calendar For additional program information: 310-443-7000 PAID Los Angeles, CA www.hammer.ucla.edu Permit no. 202 100% recycled paper (DETAIL), 1969. ASSEMBLAGE. (DETAIL), 2½ IN. COURTESY OF MICHAEL ROSENFIELD GALLERY, NY. OF MICHAEL ROSENFIELD GALLERY, 2½ IN. COURTESY BLACK GIRL’S WINDOW BLACK GIRL’S x 8 ⁄ 1 18 x BETYE SAAR. 35 ¾ 24 25 2 3 news director HAMMER NEWS the 1 from MEMBERSHIP THANK YOU message COMING UP: STUDIO VISIT a JOIN The Hammer Museum wishes to thank those who have Hammer Patrons this fall and attend the annual Patrons Studio Visit on Saturday, September 10. This year contributed acquisition funds or made gifts of works we will visit the Highland Park studios of Matt Monahan, of art since July 1, 2010. HAMMER STAFF WITH 2011 ARTIST COUNCIL 1 Lara Schnitger, and My Barbarian. Enjoy the afternoon A MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR visiting with our hosts and exploring their creative spaces. Matt Aberle Glenn Kaino Amy Adelson and Dean Valentine Margery and Maurice Katz Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945–1980 is finally here. performance by Bruno Mars. The Gala sells out every year, The Buddy Taub Foundation Patti and Frank Kolodny More than five years in the making, this citywide initiative so if you are interested in supporting the event, please UPGRADE! Seth Cohen Luisa Lambri Nan and Eugene Corman Kourosh Larizadeh and Luis Pardo spearheaded by the Getty will officially open the first weekend call 310-443-7026—but make haste! Upgrade now or join at the Supporter level ($350) or Cecilia Dan LA><ART in October to great fanfare. -

Feminist Studies > Reclaiming Histories: Betye and Alison Saar, Feminism, and the Representation of Black Womanhood

Reclaiming Histories: Betye and Alison Saar, Feminism, and the Representation of Black Womanhood Jessica Dallow The feminist movement has given me more professional exposure. But I resist that now, just like I resist exhibiting in African Amer- ican artists' shows. I've always worked the same way, and haven't done anything I would consider "feminist art." –Betye Saar Yes, I am a feminist. I was involved with the Women's Space [Womanspace] here in Los Angeles. Feminism for me implies more like humanism, just accepting yourself and knowing that it's okay to be the way you are. For me the ultimate goal is to be a whole person and to accept the outcome. –Betye Saar People aren't really ready to deal with fierce female passion. –Alison Saar Betye Saar considers herself a feminist; however she resists designating her artwork as such. Similarly, Alison Saar, Betye's daughter, avoids labeling her own art as feminist.1 Yet, both artists have helped to shape a feminist consciousness in the arts since the early 1970s through their probing constructions of autobiography, self-identity, family, and the fe- male body: a consciousness circulating around the historical develop- ment of the African American female nude. Betye's early ideas of spiritu- ality and ethnicity, shaped in the early 1970s, have germinated within her daughter, evidenced by Alison's bust- and full-length nude, non- white female figures of the 1980s and 1990s. The Saars' intergenera- tional explorations of race, history, and the black female body represent a crucial step to reclaim the contentious history surrounding the visual representation of African American women. -

Celebrating Black Culture in Art at West Los Angeles College in CONJUCTION with the MAYME A

EVENT ANNOUNCEMENT 1 of 2 pages FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DATE: January 22, 2020 CONTACT: Molly Barnes, WLAC Artist in Residence (310) 553-7626 I [email protected] 9000 Overland Ave. - Culver City, CA 90230 Celebrating Black Culture in Art at West Los Angeles College IN CONJUCTION WITH THE MAYME A. CLAYTON LIBRARY Gallery Reception: Thursday, January 30 In conjunction with the Mayme A. Clayton Library & Museum (MCLM), the West Los Angeles College Gallery will host a special exhibit throughout February in honor of Black History Month. Artifacts from the MCLM collection as well as works by 10 prominent artists will be on display. Artists include Shepard Fairey, Charles Mingus III, Mark Greenfield, Pamela Smith Hudson and Betye Saar. A public reception will be held on Thursday, January 30 in the gallery from 5:00 p.m. – 8:00 p.m. Many of the artists will be present for discussion. Admission is free. Parking is available directly adjacent to the gallery in the parking structure for $2.00 (exact change will be needed). ABOUT MCLM & THE ARTISTS: Mayme A. Clayton Library & Museum (MCLM): The MCLM collection of rare books, films, documents, photographs, artifacts, and works of art related to the history and culture of African Americans, with a special focus on Southern California and the American West, has been described as the largest of its kind on the West Coast. For 13 years, the collection was housed in Culver City across from the Veterans Auditorium. When MCLM’s lease was not renewed in summer 2019, West offered to store the pieces until a permanent home can be found. -

Betye & Alison Saar

1 Betye & Alison Saar Conjure Women of The Arts Time: 15 minutes Study Guide INTRODUCTION Betye & Alison Saar: Conjure Women of the Arts is a film about two artists, a mother and a daughter who regard themselves as colleagues, "sisters" and friends. Their relationship, contrary to competitive Western values, is more like those in African and Asian traditions, where parents commonly pass on their creative skills and knowledge. Betye Saar describes the connection as a relay race: “I've been running with my art all these years, and it's as if I have the baton and I reach back to Alison and she takes off. We're not in competition. Alison's not under my wing or my eye. I'm really proud of her. But you see, we're running the art relay for the art." Quote from article compiled by Susan Latempa for Datebook, Los Angeles. Both women use found objects in their artworks and are influenced by a variety of religions and cultures, including astrology and the occult, but each works in a unique way. Betye tends to keep the objects intact in her work, while Alison is more likely to change them in some way before incorpor-ating them in her pieces. Much of Betye's work is assemblage and collage; Alison's is sculptural, often figures with secret compartments filled with surprising artifacts and images. Both have separate careers and live on opposite ends of the country - Betye in Los Angeles and Alison in Brooklyn. Their first collaboration shown in this film was done in 1990 and reveals both their shared spirit, talent and skill and also their separate and distinct identities as women and artists. -

Being Thankful for Art November Newsletter

Being Thankful for Art November Newsletter Greetings! The Holidays are officially upon us once more, and the mad rush has begun already. But, despite the occcassional grey skies that come with the season, you can still see lots of colour throughout SoCal in the art, people, and culture of our wonderful cities. Be sure to take the time to check out the many upcoming and current shows at the local galleries! In the rush of the holiday season, and amid the mass of other things we are thankful for, let us not forget to remember the artists, sculptors, paintings, and craftspersons who bring such amazing art, inspiration and beauty into our world. And if you want to step out and see some of their works this fall, FrameStore brings you continuing coverage of the Pacific Standard Time exhibits and shows that everyone is talking about. Celebrate with FrameStore the era that continues to inspire the world! Pacific Standard Time is an unprecedented collaboration of cultural institutions across Southern California coming together to celebrate the birth of the L.A. art scene. Beginning October 2011, over 60 cultural institutions will make their contributions to this region-wide initiative encompassing every major L.A. art movement from 1945 to 1980. FrameStore has been helping southern Californians take care of their photos, artwork, and mementos correctly for over 35 years. Stop by one of our stores this week to have one of our Art and Design experts help you to turn those precious memories that will only come once into lasting and lovely art that will bring joy for decades.