Shoreline Inventory and Characterization Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Public Beach List

2021 Public Beach List - Special Rules The following is a list of popular public beaches with special rules because of resource needs and/or restrictions on harvest due to health concerns. If a beach is not listed below or on page 2, it is open for recreational harvest year-round unless closed by emergency rule, pollution or shellfish safety closures. Click for WDFW Public Beach webpages and seasons 2021 Beach Seasons adopted February 26, 2021 Open for Clams, Mussels & Oysters = Open for Oysters Only = For more information, click on beach name below to view Jan1- Jan15- Feb1- Feb15- Mar1- Mar15- Apr1- Apr15- May1- May15- Jun1- Jun15- Jul1- Jul15- Aug1- Aug15- Sep1- Sep15- Oct1- Oct15- Nov1- Nov15- Dec1- Dec15- beach-specific webpage. Jan15 Jan31 Feb15 Feb28 Mar15 Mar31 Apr15 Apr30 May15 May31 Jun15 Jun30 Jul15 Jul31 Aug15 Aug31 Sep15 Sep30 Oct15 Oct31 Nov15 Nov30 Dec15 Dec31 Ala Spit No natural production of oysters Belfair State Park Birch Bay State Park Dash Point State Park Dosewallips State Park Drayton West Duckabush Dungeness Spit/NWR Tidelands No natural production of oysters Eagle Creek Fort Flagler State Park Freeland County Park No natural production of oysters. Frye Cove County Park Hope Island State Park Illahee State Park Limited natural production of clams Indian Island County Park No natural production of oysters Kitsap Memorial State Park CLAMS AND OYSTERS CLOSED Kopachuck State Park Mystery Bay State Park Nahcotta Tidelands (Willapa Bay) North Bay Oak Bay County Park CLAMS AND OYSTERS CLOSED Penrose Point State Park Point -

RCFB April 2021 Page 1 Agenda TUESDAY, April 27 OPENING and MANAGEMENT REPORTS 9:00 A.M

REVISED 4/8/21 Proposed Agenda Recreation and Conservation Funding Board April 27, 2021 Online Meeting ATTENTION: Protecting the public, our partners, and our staff are of the utmost importance. Due to health concerns with the novel coronavirus this meeting will be held online. The public is encouraged to participate online and will be given opportunities to comment, as noted below. If you wish to participate online, please click the link below to register and follow the instructions in advance of the meeting. Technical support for the meeting will be provided by RCO’s board liaison who can be reached at [email protected]. Registration Link: https://zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_JqkQAGCrRSOwbHLmg3a6oA Phone Option: (669)900-6833 - Webinar ID: 967 5491 2108 Location: RCO will also have a public meeting location for members of the public to listen via phone as required by the Open Public Meeting Act, unless this requirement is waived by gubernatorial executive order. In order to enter the building, the public must not exhibit symptoms of the COVID-19 and will be required to comply with current state law around personal protective equipment. RCO staff will meet the public in front of the main entrance to the natural resources building and escort them in. *Additionally, RCO will record this meeting and would be happy to assist you after the meeting to gain access to the information. Order of Presentation: In general, each agenda item will include a short staff presentation and followed by board discussion. The board only makes decisions following the public comment portion of the agenda decision item. -

San Juan Island National Historical Park Natural Resource Condition Assessment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science San Juan Island National Historical Park Natural Resource Condition Assessment Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/WRD/NRR—xxxx ON THE COVER Looking east from the park, toward Lopez Island and Strait of Juan de Fuca. Photo by Peter Dunwiddie. San Juan Island National Historical Park Natural Resource Condition Assessment Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/WRD/NRR—xxx Paul R. Adamus Water Resources Science Program Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon and Adamus Resource Assessment, Inc. Corvallis, Oregon Peter Dunwiddie University of Washington Seattle, Washington Anna Pakenham Marine Resource Management Program Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon This report was prepared under Task Agreement P12AC15016 (Cooperative Agreement H8W07110001) between the National Park Service and Oregon State University September 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with -

PROVINCI L Li L MUSEUM

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA REPORT OF THE PROVINCI_l_Li_L MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY • FOR THE YEAR 1930 PRINTED BY AUTHORITY OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. VICTORIA, B.C. : Printed by CHARLES F. BANFIELD, Printer to tbe King's Most Excellent Majesty. 1931. \ . To His Honour JAMES ALEXANDER MACDONALD, Administrator of the Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOUR: The undersigned respectfully submits herewith the Annual Report of the Provincial Museum of Natural History for the year 1930. SAMUEL LYNESS HOWE, Pt·ovincial Secretary. Pt·ovincial Secretary's Office, Victoria, B.O., March 26th, 1931. PROVINCIAl. MUSEUM OF NATURAl. HISTORY, VICTORIA, B.C., March 26th, 1931. The Ho1Wm·able S. L. Ho11ie, ProvinciaZ Secreta11}, Victo1·ia, B.a. Sm,-I have the honour, as Director of the Provincial Museum of Natural History, to lay before you the Report for the year ended December 31st, 1930, covering the activities of the Museum. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, FRANCIS KERMODE, Director. TABLE OF CONTENTS . PAGE. Staff of the Museum ............................. ------------ --- ------------------------- ----------------------------------------------------- -------------- 6 Object.. .......... ------------------------------------------------ ----------------------------------------- -- ---------- -- ------------------------ ----- ------------------- 7 Admission .... ------------------------------------------------------ ------------------ -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Part IX: References

This page was intentionally left blank References Able, K.P.; Noon, B.R. 1977. Avian community structure Agee, J.K.; Flewelling, R. 1983. A fire cycle model based along elevational gradients in the northeastern United on climate for the Olympic Mountains, Washington. Fire States. Oecologia. 26(3):275-294. and Forest Meteorology Conferences. 7:32-37. Adams, D.P. 1986. Quaternary pollen records from Califor- Agee, J.K.; Huff, M.H. 1987. Fuel succession in a western nia. In: Bryant, V.M., Jr.; Holloway, R.G., eds. Pollen hemlock/Douglas-fir forest. Canadian Journal of Forest records of Late-Quaternary North American sediments. Research. 17(7):697-704. Austin, TX: American Association of Stratigraphic Paly- nologists Foundation: 125-140. Alaback, P.B. 1982. Dynamics of understory biomass in Sitka spruce-western hemlock forests of southeast Alaska. Afifi, A.A.; Clark, V. 1984. Computer-aided multivariate Ecology. 63(6): 1932-1948. analysis. Belmont, CA: Lifetime Publications, Wadsworth, Inc. 458 p. Alaback, P.B. 1984. A comparison of old-growth and second-growth forest structure in the western hemlock- Agee, J.K. 1989. A history of fire and slash burning in west- Sitka spruce forests of southeastern Alaska. In: Meehan, em Oregon and Washington. In: Hanley, D.P.; Kammenga, W.R.; Merrell, T.R. Jr.; Hartley, T.A., eds. Fish and J.J.; Oliver, C.D., eds. The burning decision: a regional wildlife relationships in old-growth forests. Proceedings symposium on slash. Contribution 66. Seattle: College of of a symposium; 1982 April 12-15; Juneau, AK. Forest Resources, University of Washington, Institute of Morehead City, NC: American Institute of Fishery Forest Resources: 3-20. -

Washington State's Scenic Byways & Road Trips

waShington State’S Scenic BywayS & Road tRipS inSide: Road Maps & Scenic drives planning tips points of interest 2 taBLe of contentS waShington State’S Scenic BywayS & Road tRipS introduction 3 Washington State’s Scenic Byways & Road Trips guide has been made possible State Map overview of Scenic Byways 4 through funding from the Federal Highway Administration’s National Scenic Byways Program, Washington State Department of Transportation and aLL aMeRican RoadS Washington State Tourism. waShington State depaRtMent of coMMeRce Chinook Pass Scenic Byway 9 director, Rogers Weed International Selkirk Loop 15 waShington State touRiSM executive director, Marsha Massey nationaL Scenic BywayS Marketing Manager, Betsy Gabel product development Manager, Michelle Campbell Coulee Corridor 21 waShington State depaRtMent of tRanSpoRtation Mountains to Sound Greenway 25 Secretary of transportation, Paula Hammond director, highways and Local programs, Kathleen Davis Stevens Pass Greenway 29 Scenic Byways coordinator, Ed Spilker Strait of Juan de Fuca - Highway 112 33 Byway leaders and an interagency advisory group with representatives from the White Pass Scenic Byway 37 Washington State Department of Transportation, Washington State Department of Agriculture, Washington State Department of Fish & Wildlife, Washington State Tourism, Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission and State Scenic BywayS Audubon Washington were also instrumental in the creation of this guide. Cape Flattery Tribal Scenic Byway 40 puBLiShing SeRviceS pRovided By deStination -

San Juan Channel NOAA Chart 18434

BookletChart™ San Juan Channel NOAA Chart 18434 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Included Area Published by the entrance to Blind Bay, Shaw Island; Orcas, Orcas Island; and Friday Harbor, San Juan Island. Oceangoing vessels normally use Haro and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Rosario Straits and do not run the channels and passes in the San Juan National Ocean Service Islands. Many resorts and communities have supplies and moorage Office of Coast Survey available for the numerous pleasure craft cruising in these waters. Well- sheltered anchorages are numerous. www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov Haro Strait and Boundary Pass form the westernmost of the three main 888-990-NOAA channels leading from the Strait of Juan de Fuca to the SE end of the Strait of Georgia; it is the one most generally used. Vessels bound from What are Nautical Charts? the W to ports in Alaska or British Columbia should use the Haro Strait/ Boundary Pass channel, as it is the widest channel and is well marked. Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show Vessels bound N from Puget Sound may use Rosario Strait or Haro Strait; water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much the use of San Juan Channel by deep-draft vessels is not recommended. more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and A Vessel Traffic Service has been established in the Strait of Juan de efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial Fuca, E of Port Angeles, and in the adjacent waters. -

San Juan County Community Wildfire Protection Plan Steering Committee

San Juan County, Washington Community Wildfire Protection Plan/Wildfire Risk Assessment 2010 Satellite Island Fire Adopted by the San Juan County Council August 2012 This plan was developed by the San Juan County Community Wildfire Protection Plan steering committee. Acknowledgements This Community Wildfire Protection Plan represents the efforts and cooperation of a number of organizations and agencies working together to improve preparedness for wildfire events while reducing factors of risk. Waldron Island Fire Brigade 2012 - /Wildfire Risk Assessment /Wildfire Community Wildfire Protection Wildfire Plan Community Washington Washington To obtain copies of this plan contact: County, San Juan County Emergency Management PO Box 669 Friday Harbor, WA 98250 360-370-7612 [email protected] San Juan Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................................ II FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1 ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 OVERVIEW OF THIS PLAN AND ITS DEVELOPMENT ....................................................................................................... 3 GOALS AND GUIDING PRINCIPLES -

National List of Beaches 2004 (PDF)

National List of Beaches March 2004 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington DC 20460 EPA-823-R-04-004 i Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 States Alabama ............................................................................................................... 3 Alaska................................................................................................................... 6 California .............................................................................................................. 9 Connecticut .......................................................................................................... 17 Delaware .............................................................................................................. 21 Florida .................................................................................................................. 22 Georgia................................................................................................................. 36 Hawaii................................................................................................................... 38 Illinois ................................................................................................................... 45 Indiana.................................................................................................................. 47 Louisiana -

Fishes-Of-The-Salish-Sea-Pp18.Pdf

NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 18 Fishes of the Salish Sea: a compilation and distributional analysis Theodore W. Pietsch James W. Orr September 2015 U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Professional Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce Papers NMFS National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. Sullivan Scientifi c Editor Administrator Richard Langton National Marine Fisheries Service National Marine Northeast Fisheries Science Center Fisheries Service Maine Field Station Eileen Sobeck 17 Godfrey Drive, Suite 1 Assistant Administrator Orono, Maine 04473 for Fisheries Associate Editor Kathryn Dennis National Marine Fisheries Service Offi ce of Science and Technology Fisheries Research and Monitoring Division 1845 Wasp Blvd., Bldg. 178 Honolulu, Hawaii 96818 Managing Editor Shelley Arenas National Marine Fisheries Service Scientifi c Publications Offi ce 7600 Sand Point Way NE Seattle, Washington 98115 Editorial Committee Ann C. Matarese National Marine Fisheries Service James W. Orr National Marine Fisheries Service - The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS (ISSN 1931-4590) series is published by the Scientifi c Publications Offi ce, National Marine Fisheries Service, The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series carries peer-reviewed, lengthy original NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, fl ora and fauna studies, and data- Seattle, WA 98115. intensive reports on investigations in fi shery science, engineering, and economics. The Secretary of Commerce has Copies of the NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series are available free in limited determined that the publication of numbers to government agencies, both federal and state. They are also available in this series is necessary in the transac- exchange for other scientifi c and technical publications in the marine sciences. -

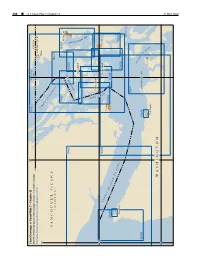

CPB7 C12 WEB.Pdf

488 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 7, Chapter 12 Chapter 7, Pilot Coast U.S. 124° 123° Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 7—Chapter 12 18421 BOUNDARY NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage BAY CANADA 49° http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml UNITED STATES S T R Blaine 125° A I T O F G E O R V ANCOUVER ISLAND G (CANADA) I A 18431 18432 18424 Bellingham A S S Y P B 18460 A R 18430 E N D L U L O I B N G Orcas Island H A M B A Y H A R O San Juan Island S T 48°30' R A S I Lopez Island Anacortes T 18465 T R A I Victoria T O F 18433 18484 J 18434 U A N D E F U C Neah Bay A 18427 18429 SKAGIT BAY 18471 A D M I R A L DUNGENESS BAY T 18485 18468 Y I N Port Townsend L E T Port Angeles W ASHINGTON 48° 31 MAY 2020 31 MAY 31 MAY 2020 U.S. Coast Pilot 7, Chapter 12 ¢ 489 Strait of Juan De Fuca and Georgia, Washington (1) thick weather, because of strong and irregular currents, ENC - extreme caution and vigilance must be exercised. Chart - 18400 Navigators not familiar with these waters should take a pilot. (2) This chapter includes the Strait of Juan de Fuca, (7) Sequim Bay, Port Discovery, the San Juan Islands and COLREGS Demarcation Lines its various passages and straits, Deception Pass, Fidalgo (8) The International Regulations for Preventing Island, Skagit and Similk Bays, Swinomish Channel, Collisions at Sea, 1972 (72 COLREGS) apply on all the Fidalgo, Padilla, and Bellingham Bays, Lummi Bay, waters of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Haro Strait, and Strait Semiahmoo Bay and Drayton Harbor and the Strait of of Georgia. -

The Totem Line 53 Years of Yachting - 54 Years of Friendship

Volume 55 Issue 3 Our 55th Year March 2010 The Totem Line 53 years of yachting - 54 years of friendship In this issue…Annual awards announced; Membership drive emphasis; Consider WA marine parks Upcoming Events Commodore.………………...….…. Ray Sharpe [email protected] Mar 2…………..…………...…General Meeting Mar 6………... Des Moines Commodore’s Ball Vice Commodore…………… Gene Mossberger Mar 16…………...…………..… Board Meeting [email protected] Mar 17…………….NBC Meeting at Totem YC Mar 18 – 21..….…………Anacortes Boat Show Rear Commodore…….…………….Bill Sheehy Mar 19 – 21.….……………Coming Out Cruise [email protected] Mar 27………....…….………….....Spring Fling C ommodore’s Report The Membership Yearbook is Area Fuel Prices going to print shortly and should http://fineedge.com/fuelsurvey.html be ready for the March general Updated 1/27/10 meeting. Thanks to Gene, Dan and Mary for their efforts. C ommodore (Cont’d) by itself. If there isn’t some one willing to take on I want to thank Gene and Patti the organizing of this event and make it a great end of Mossberger, Bill and Val summer happening, then we need to decide now so Sheehy, and Rocci and Sharon Blair for attending the club can let Fair Harbor know that we’re not The TOA Commodores Ball with Char and myself going to do it. Then they can have it available to other and supporting Totem Yacht Club. boaters that may want it. Last year was a last minute scramble by some dedicated members. It is a lot Val Sheehy has stepped forward to take on the easier if it is done with proper planning.