Gnostics of the North, Or Music to Recolonize Your Anxious Capitalist Dreams by Seth Kim-Cohen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1St Edition)

R O C K i n t h e R E S E R V A T I O N Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1st edition). (text, 2004) Yngvar B. Steinholt. New York and Bergen, Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. viii + 230 pages + 14 photo pages. Delivered in pdf format for printing in March 2005. ISBN 0-9701684-3-8 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt (b. 1969) currently teaches Russian Cultural History at the Department of Russian Studies, Bergen University (http://www.hf.uib.no/i/russisk/steinholt). The text is a revised and corrected version of the identically entitled doctoral thesis, publicly defended on 12. November 2004 at the Humanistics Faculty, Bergen University, in partial fulfilment of the Doctor Artium degree. Opponents were Associate Professor Finn Sivert Nielsen, Institute of Anthropology, Copenhagen University, and Professor Stan Hawkins, Institute of Musicology, Oslo University. The pagination, numbering, format, size, and page layout of the original thesis do not correspond to the present edition. Photographs by Andrei ‘Villi’ Usov ( A. Usov) are used with kind permission. Cover illustrations by Nikolai Kopeikin were made exclusively for RiR. Published by Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. 401 West End Avenue # 3B New York, NY 10024 USA Preface i Acknowledgements This study has been completed with the generous financial support of The Research Council of Norway (Norges Forskningsråd). It was conducted at the Department of Russian Studies in the friendly atmosphere of the Institute of Classical Philology, Religion and Russian Studies (IKRR), Bergen University. -

David Menconi

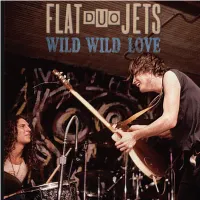

David Menconi “But tonight, we’re experiencing something much more demented. Something much more American. And something much more crazy. I put it to you, Bob: Goddammit, what’s goin’ on?” —Dexter Romweber, “2 Headed Cow” (1986) (Or as William Carlos Williams put it 63 years earlier: “The Pure Products of America/Go crazy.”) To the larger world outside the Southeastern college towns of Chapel Hill and Athens, Flat Duo Jets’ biggest brush up against the mainstream came with the self-titled first album comprising the heart of this collection. That was 1990’s “Flat Duo Jets,” a gonzo blast of interstellar rockabilly firepower that turned Jack White, X’s Exene Cervenka and oth- er latterday American underground-rock stars into fans and acolytes. In its wake, the Jets toured America with The Cramps and played “Late Night with David Letterman,” astounding audiences with rock ’n’ roll as pure and uncut as anybody was making in the days B.N. (Before Nirvana). But that kind of passionate devotion was nothing new for the Jets. For years, they’d been turning heads and blowing minds in their Chapel Hill home- town as a veritable rite of passage for music-scene denizens of a certain age. Just about everyone in town from that era has a story about happening across the Jets in their mid-’80s salad days, often performing in some terri- bly unlikely place – record store, coffeeshop, hallway, even the middle of the street – channeling some far-off mojo that seemed to open portals to the past and future at the same time. -

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel B.S. Physics Hobart and William Smith Colleges, 2004 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2008 © 2008 Evan Landon Wendel. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _______________________________________________________ Program in Comparative Media Studies May 9, 2008 Certified By: _____________________________________________________________ William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Accepted By: _____________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies 2 3 New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 9, 2008 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract This thesis explores the evolving nature of independent music practices in the context of offline and online social networks. The pivotal role of social networks in the cultural production of music is first examined by treating an independent record label of the post- punk era as an offline social network. -

1 : Daniel Kandi & Martijn Stegerhoek

1 : Daniel Kandi & Martijn Stegerhoek - Australia (Original Mix) 2 : guy mearns - sunbeam (original mix) 3 : Close Horizon(Giuseppe Ottaviani Mix) - Thomas Bronzwaer 4 : Akira Kayos and Firestorm - Reflections (Original) 5 : Dave 202 pres. Powerface - Abyss 6 : Nitrous Oxide - Orient Express 7 : Never Alone(Onova Remix)-Sebastian Brandt P. Guised 8 : Salida del Sol (Alternative Mix) - N2O 9 : ehren stowers - a40 (six senses remix) 10 : thomas bronzwaer - look ahead (original mix) 11 : The Path (Neal Scarborough Remix) - Andy Tau 12 : Andy Blueman - Everlasting (Original Mix) 13 : Venus - Darren Tate 14 : Torrent - Dave 202 vs. Sean Tyas 15 : Temple One - Forever Searching (Original Mix) 16 : Spirits (Daniel Kandi Remix) - Alex morph 17 : Tallavs Tyas Heart To Heart - Sean Tyas 18 : Inspiration 19 : Sa ku Ra (Ace Closer Mix) - DJ TEN 20 : Konzert - Remo-con 21 : PROTOTYPE - Remo-con 22 : Team Face Anthem - Jeff Mills 23 : ? 24 : Giudecca (Remo-con Remix) 25 : Forerunner - Ishino Takkyu 26 : Yomanda & DJ Uto - Got The Chance 27 : CHICANE - Offshore (Kitch 'n Sync Global 2009 Mix) 28 : Avalon 69 - Another Chance (Petibonum Remix) 29 : Sophie Ellis Bextor - Take Me Home 30 : barthez - on the move 31 : HEY DJ (DJ NIKK HARDHOUSE MIX) 32 : Dj Silviu vs. Zalabany - Dearly Beloved 33 : chicane - offshore 34 : Alchemist Project - City of Angels (HardTrance Mix) 35 : Samara - Verano (Fast Distance Uplifting Mix) http://keephd.com/ http://www.video2mp3.net Halo 2 Soundtrack - Halo Theme Mjolnir Mix declub - i believe ////// wonderful Dinka (trance artist) DJ Tatana hard trance ffx2 - real emotion CHECK showtek - electronic stereophonic (feat. MC DV8) Euphoria Hard Dance Awards 2010 Check Gammer & Klubfiller - Ordinary World (Damzen's Classix Remix) Seal - Kiss From A Rose Alive - Josh Gabriel [HQ] Vincent De Moor - Fly Away (Vocal Mix) Vincent De Moor - Fly Away (Cosmic Gate Remix) Serge Devant feat. -

Art Terrorism in Ohio: Cleveland Punk, the Mimeograph Revolution, Devo, Zines, Artists’ Periodicals, and Concrete Poetry, 1964-2011

Art Terrorism in Ohio: Cleveland Punk, The Mimeograph Revolution, Devo, Zines, Artists’ Periodicals, and Concrete Poetry, 1964-2011. The Catalog for the Inaugural Exhibition at Division Leap Gallery. Part 1: Cleveland Punk [Nos. 1-22] Part 2: Devo, Evolution, & The Mimeograph Revolution [Nos. 23-33] Part 3: Zines, Artists’ Periodicals, The Mimeograph Revolution & Poetry [Nos.34-100] This catalog and exhibition arose out two convictions; that the Cleveland Punk movement in the 70’s is one of the most important and overlooked art movements of the late 20th century, and that it is fruitful to consider it in context of its relationship with several other equally marginalized contemporary postwar Ohio art movements in print; The Mimeograph Revolution, the zine movement, concrete poetry, and mail art. Though some pioneering music criticism, notably the work of Heylin and Savage, has placed Cleveland as being of central importance to the proto-punk narrative, it remains largely marginalized as an art movement. This may be because of geographical bias; Cleveland is a long way from New York or London. This is despite the fact that the bands involved were heavily influenced by previous art movements, especially the electric eels, who, informed by Viennese Aktionism, Albert Ayler, and theories of anti- music, were engaged in a savage form of performance art which they termed “Art Terrorism” which had no parallel at the time (and still doesn’t). It is tempting to imagine what response the electric eels might have had in downtown New York in the early 70’s, being far more provocative than their distant contemporaries Suicide. -

CLINE-DISSERTATION.Pdf (2.391Mb)

Copyright by John F. Cline 2012 The Dissertation Committee for John F. Cline Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Permanent Underground: Radical Sounds and Social Formations in 20th Century American Musicking Committee: Mark C. Smith, Supervisor Steven Hoelscher Randolph Lewis Karl Hagstrom Miller Shirley Thompson Permanent Underground: Radical Sounds and Social Formations in 20th Century American Musicking by John F. Cline, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my mother and father, Gary and Linda Cline. Without their generous hearts, tolerant ears, and (occasionally) open pocketbooks, I would have never made it this far, in any endeavor. A second, related dedication goes out to my siblings, Nicholas and Elizabeth. We all get the help we need when we need it most, don’t we? Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation supervisor, Mark Smith. Even though we don’t necessarily work on the same kinds of topics, I’ve always appreciated his patient advice. I’m sure he’d be loath to use the word “wisdom,” but his open mind combined with ample, sometimes non-academic experience provided reassurances when they were needed most. Following closely on Mark’s heels is Karl Miller. Although not technically my supervisor, his generosity with his time and his always valuable (if sometimes painful) feedback during the dissertation writing process was absolutely essential to the development of the project, especially while Mark was abroad on a Fulbright. -

2016 ... We Are Devo! at Least Over 90 ‘We Are Devo’ Related Items in Planner Project 2016!

1 PLANNER PROJECT (PP) 2016 ... WE ARE DEVO! AT LEAST OVER 90 ‘WE ARE DEVO’ RELATED ITEMS IN PLANNER PROJECT 2016! 1/1 After rocking to the ‘Eric Carmen Band’ at the Agora on the 30th (with 5 encores); ‘Pere Ubu’ & ‘Frankenstein’ bring in the new year at the Viking Saloon, 2005 Chester, 1976 1/14 “I’ll open somewhere,” manager Dick Korn tells the Plain Dealer, after fire on January 7th causes $25,000 damage to the Viking Saloon rock house at 2005 Chester, 1976 1/20 As 43-year-old John F. Kennedy is sworn in as President, stating, “Ask not what your country can do for you - ask what you can do for your country;” hot singles include: The Miracles’ ‘Shop Around;’ Neil Sedaka’s ‘Calendar Girl;’ Elvis Presley’s ‘Are You Lonesome Tonight;’ The Drifters’ ‘I Count the Tears’ & ‘Ruby’ by Ray Charles, 1961 1/11 “Once we played that (‘Ziggy Stardust’), it was over. People fell in love with David Bowie in Cleveland,” notes former WMMS-FM disc jockey and program director Billy Bass, remembering the rock superstar upon his passing today at age 69, 2016 1/21 “We put pride back into Cleveland,’ states WMMS-FM’s Kid Leo after Cleveland tops the USA Today Rock Hall site poll with 110,315 votes-103,047 over Memphis, 1986 1/26 While downstairs, Jimmy Ley & his Coosa River Band rock the Mistake both nights, making her first trip here, Patti Smith opens the first of two soldout nights with Tom Rapp at the Agora on E. -

The College News 1989-2-2 Vol. 10 No. 7 (Bryn Mawr, PA: Bryn Mawr College, 1989)

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Bryn Mawr College Publications, Special Bryn Mawr College News Collections, Digitized Books 1989 The olC lege News 1989-2-2 Vol. 10 No. 7 Students of Bryn Mawr College Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_collegenews Custom Citation Students of Bryn Mawr College, The College News 1989-2-2 Vol. 10 No. 7 (Bryn Mawr, PA: Bryn Mawr College, 1989). This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_collegenews/1401 For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME X Number February 2, 1989 Plenary: quick quorum; new Code adopted Denison WOOS Myers & family tives and freshwornen to understand? Karen Tidmarsh believes that the BYBEfflSTROUD However, when Carrie Wofford voiced this con- Sophomore Humanities Seminar, which is cern by calling the proposed Code "an Honor being offered for the first time this semester, It may have been the beat Plenary any- Code for juniors and seniors, not for sophomores "wouldn't have happened without her [Dean one remembers We reached quorum—400 and freshmen," suggesting that newer students Myers'] leadership and encouragement." people-by 7:15, COLOR held a bake sale with might not have the background and experience to When Dean Myers first came to Bryn Mawr, chocolate chip cookies and lemon pound cake, Ka- interpret a more generalized i Code, two she strongly believed that the College needed ty Coyie's band, "Kate and the Electric Fish" was freshwornen responded with some of the most to' 'focus more on interdisciplinary [courses] hot, and President McPherson danced on stage passionate speeches of the evening in favor of the and 'general education'." The Humanities with Katy to "Johnnie R Goode" Also, six resolu- resolution. -

Fan Records Laughner Tapes by Jane Scott Cleveland Plain Dealer Friday, July 16, 1982

Fan records Laughner tapes By Jane Scott Cleveland Plain Dealer Friday, July 16, 1982 Word-renowned Cleveland rock writer Jane Scott was a big fan of Pete's. “I only met him once. I saw him play at the Pirate’s Cove five or six times, though, back in the winter of ’76. I couldn’t forget his guitar. It was amazing. He was so honest,” said Doug Morgan. Morgan was a high school student from Chagrin Falls then. Today he is 24, the same age that guitarist/singer/poet Peter Laughner was when he died in his sleep five years ago. Morgan has done what many others have told you that they were going to do. He put out a 12-ince EP of Laughner’s tapes. The seven-song album on Koolie Records, just called “Peter Laughner,” is a good representation of the many aspects of Laughner’s short life. John Sipl helped mix it at Kirk Yano’s After Dark Studio. They are not studio songs with hours of recording expertise behind them. You can see where better apparatus would have helped. But the feeling and the sincerity come across and remind you again of how much we have lost. One, “Rag Mama,” recorded by Laughner on a Nakamichi cassette at his parents’ home in Bay Village, is rather lightweight but catch and fun, an up tempo ragtime. One, “Dinosaur Lullaby,” is an instrumental, rather dissonant. It was recorded live at a WMMS “Coffeebreak Concert,” as was my favorite on the LP, “Baudelaire.” Laughner had been a dinosaur freak since he was 5. -

Babylon's Burning BAT.Qxd 11/10/07 11:49 Page 3

Babylon's burning BAT.qxd 11/10/07 11:49 Page 3 Clinton Heylin Babylon’s burning Traduit de l’anglais par STAN CUESTA Babylon's burning BAT.qxd 11/10/07 11:49 Page 5 Prologue Au début était le Verbe… Mon favori pour le titre de « premier punk » est né sous le nom de Leslie Conway, dans un hôpital de la périphérie de San Diego, Californie, en décembre 1948, le parfait baby-boomer. Sa mère était une fanatique des Témoins de Jéhovah, son père un alcoo- lique, qui a disparu de la vie de son fils avant qu’il n’ait dix ans. Lester Bangs – puisque c’est de lui dont il s’agit – a passé la majeure partie de sa vie à vouloir rentrer chez lui, spirituellement parlant, et à s’enfuir, physiquement et intellectuellement. Lester était vendeur de chaussures quand il a réalisé qu’il avait autant à dire que les Greil Marcus et autres Paul Williams qui définissaient alors l’écriture rock. Après une plongée intensive sous amphétamines typiquement beat, enfermé et défoncé au déca- pant, à passer toute une nuit en boucle les deux premiers albums du Velvet, Bangs a décidé d’envoyer une chronique du second, véritable orgie bruitiste, au bastion underground de l’écriture rock, Rolling Stone, basé à plus de mille kilomètres au nord sur la 5 Highway One, à San Francisco. Son évangélisme semeur de dis- corde n’était pas ce dont le patron, Jann Wenner, pensait avoir besoin, mais Bangs ne s’est pas découragé et a envoyé dans la fou- lée une chronique du Kick Out The Jams du MC5 que le journal a publiée dans son édition du 6 avril 1969. -

Für Sonntag, 21

InfoMail 23.08.16: Deutsches Musikmagazin "Rolling Stone" mit BEATLES-Titelstory und CD REVOLVER RELOADAD /// MANY YEARS AGO Weitere Info und/oder bestellen: Einfach Abbildung anklicken WhatsApp für MegaKurzInfo: Bitte eine WhatsApp senden: 01578-0866047 (Nummer speziell für WhatsApp geschaltet.) Hallo M.B.M.! Hallo BEATLES-Fan! Im Beatles Museum erhältlich: Deutsche Musikzeitschrift "Rolling Stone" mit Titelstory THE BEATLES - 50 JAHRE REVOLVER und CD REVOLVER RELOADED August 2016: Deutsche Musikzeitschrift "Rolling Stone", Ausgabe 262. 6,90 € Verlag: Axel Springer, Deutschland. Hochformat ca. 30,0 cm x 23,0 cm; 116 Seiten (Titelseite und weitere 14 Seiten über BEATLES); sehr viele Fotos (davon 15 BEATLLES-Fotos); deutschsprachig. Inhalt des Magazins: Titelthema: THE BEATLES - 50 Jahre REVOLVER: Im Jahr 1966 nahmen die BEATLES ihr bestes Album auf und kehrten der Welt den Rücken. Maik Brüggemeyer über REVOLVER und die Folgen. Plus: Coverkünstler KLAUS VOORMANN erzählt seine Geschichte als Graphic Novel. Abbildungen: Magazin mit CD REVOLVER RELOADED weitere Themen: RS-Reportage: Die rechten Hipster: Die "Identitäre Bewegung" inszeniert sich als hippe rechte Kultur - mit "Neofolk" als Soundtrack. Fabian Peltsch und Ralf Niemczyk haben sich in der befremdlichen Nischenwelt umgesehen. Ryley Walker: In Flip-Flops zum Gipfel: Unrasiert, verkatert und auf dem Sprung zum Star: Ryley Walker brilliert mit Psych-Folk. Jan Jekal trifft den Songwriter aus Chicago zu einem Gespräch über Gitarren, Pink Floyd und Europa. Dinosaur Jr.: Der andere Classic Rock: Seit mehr als 30 Jahren sind Dinosaur Jr. eine der besten Rockbands des Planeten, kommen aber ohne Klischees aus. Max Grösche spricht mit Lou Barlow und J. Mascis. Von Neil Young bis Campino: Storys und interviews: Maxim, Hatsune Miku, Torsten Sträter, Adiam, Bear's Den, Rio Reiser u. -

30 Seconds Over CLE Cleveland’S Godfather of Underground Rock, Pere Ubu’S David Thomas, Returns Home

lake effect / PUBLIC SQUARE :: ideas, gripes & good news 30 Seconds Over CLE Cleveland’s godfather of underground rock, Pere Ubu’s David Thomas, returns home. / BY DILLON STEWART / KICK GAME SNEAKER COLLECTING’S allure goes beyond rocking fresh kicks. Copping limited edition Yeezys or Air Jordans is about the challenge. The shoe is simply a trophy. But Cleveland sneakerheads have a new game to play at the Restock, a Joe Haden-owned menswear shop downtown, and it doesn’t include waiting in line or scouring the internet. Among the racks of rare streetwear finds sits the Key Master, an arcade game ubiqui- tous in malls that typically spits out gift cards and off-brand MP3 players. Restock’s Key Master, however, awards some of the sneaker world’s most David Thomas, second elusive prizes. from left, and Pere Ubu Stocked with shoes that return to Cleveland to range from $500 to more than support their new album. $1,000, the $5-a-turn machine might seem too good to be true. But that’ll change when hese days, Cleveland is just another airport for David Thomas. “It’s not anywhere more special you actually try it, says David than anywhere else,” says the lead singer of the proto-punk band Rocket From the Tombs and VanGieson, a buyer at Restock. its aftermath, pre-new wave band Pere Ubu. But during the 1970s, Thomas found inspiration To win, contestants must in the city’s gritty disintegration and helped spawn an underground music scene that influ- position a golden key to fit a enced bands from the Ramones to Devo to Nirvana.