Commercial Sail A.Y.R.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corinthian Yacht Club of Seattle Race Book

R A C E B O O K 2 0 1 8 Sharing the Sailing Community More Jubilee – 2017 Boat of the Year Skipper: Erik Kristen Corinthian Yacht Club of Seattle Race Book 2018 Updated February 23, 2018 7755 Seaview Ave NW, Pier V Seattle, Washington 98117 www.cycseattle.org ⦁ 206.789.1919 ⦁ [email protected] Contents Let’s Go Sailing! .............................................................................................................................................. 1 About the Club ................................................................................................................................................ 2 Club Programs ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Racing Calendar ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Race Registration .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Entry Fees and Season’s Passes ............................................................................................................. 6 Lake Washington Racing ........................................................................................................................... 7 Last Season’s Regatta Winners ......................................................................................................... 7 Notice of Race Lake -

Appropriate Sailing Rigs for Artisanal Fishing Craft in Developing Nations

SPC/Fisheries 16/Background Paper 1 2 July 1984 ORIGINAL : ENGLISH SOUTH PACIFIC COMMISSION SIXTEENTH REGIONAL TECHNICAL MEETING ON FISHERIES (Noumea, New Caledonia, 13-17 August 1984) APPROPRIATE SAILING RIGS FOR ARTISANAL FISHING CRAFT IN DEVELOPING NATIONS by A.J. Akester Director MacAlister Elliott and Partners, Ltd., U.K. and J.F. Fyson Fishery Industry Officer (Vessels) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy LIBRARY SOUTH PACIFIC COMMISSION SPC/Fisheries 16/Background Paper 1 Page 1 APPROPRIATE SAILING RIGS FOR ARTISANAL FISHING CRAFT IN DEVELOPING NATIONS A.J. Akester Director MacAlister Elliott and Partners, Ltd., U.K. and J.F. Fyson Fishery Industry Officer (Vessels) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy SYNOPSIS The plight of many subsistence and artisanal fisheries, caused by fuel costs and mechanisation problems, is described. The authors, through experience of practical sail development projects at beach level in developing nations, outline what can be achieved by the introduction of locally produced sailing rigs and discuss the choice and merits of some rig configurations. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. RISING FUEL COSTS AND THEIR EFFECT ON SMALL MECHANISED FISHING CRAFT IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES 3. SOME SOLUTIONS TO THE PROBLEM 3.1 Improved engines and propelling devices 3.2 Rationalisation of Power Requirements According to Fishing Method 3.3 The Use of Sail 4. SAILING RIGS FOR SMALL FISHING CRAFT 4.1 Requirements of a Sailing Rig 4.2 Project Experience 5. DESCRIPTIONS OF RIGS USED IN DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS 5.1 Gaff Rig 5.2 Sprit Rig 5.3 Lug Sails 5.3.1 Chinese type, fully battened lug sail 5.3.2 Dipping lug 5.3.3 Standing lug 5.4 Gunter Rig 5.5 Lateen Rig 6. -

Boom Vang Rigging

Congratulations! You purchased the best known and best built pocket cruising vessels available. We invite you to spend a few moments with the following pages to become better acquainted with your new West Wight Potter. If at any point we can assist you, please call 800 433 4080 Fair Winds International Marine Standing Rigging The mast is a 2” aluminum extrusion with a slot on the aft side to which the sail’s boltrope or mainsail slides (options item) enter when hoisting the main sail. Attached to the mast will be two side stays, called Shrouds, and a Forestay. These three stainless cables represent the standing rigging of the West Wight Potter 15. The attachment points for the shroud adjusters are on the side of the deck. Looking at the boat you will find ¼” U-Bolts mounted through the deck on either side of the boat and the adjuster goes over these U-Bolts. Once the shroud adjuster slides in, the clevis pin inserts through the adjuster and is held in place with a lock ring. When both side stays are in place we move onto the mast raising. Mast Raising First, remove the mast pin holding the mast base in the bow pulpit. Second, move the mast back towards the mast step on the cabin top of the boat and pin the mast base into the aft section of the mast step (the mast step is bolted onto the cabin top of the boat). The mast crutch on the transom of the boat will support the aft end of the mast. -

Journal of the of Association Yachting Historians

Journal of the Association of Yachting Historians www.yachtinghistorians.org 2019-2020 The Jeremy Lines Access to research sources At our last AGM, one of our members asked Half-Model Collection how can our Association help members find sources of yachting history publications, archives and records? Such assistance should be a key service to our members and therefore we are instigating access through a special link on the AYH website. Many of us will have started research in yacht club records and club libraries, which are often haphazard and incomplete. We have now started the process of listing significant yachting research resources with their locations, distinctive features, and comments on how accessible they are, and we invite our members to tell us about their Half-model of Peggy Bawn, G.L. Watson’s 1894 “fast cruiser”. experiences of using these resources. Some of the Model built by David Spy of Tayinloan, Argyllshire sources described, of course, are historic and often not actively acquiring new material, but the Bartlett Over many years our friend and AYH Committee Library (Falmouth) and the Classic Boat Museum Member the late Jeremy Lines assiduously recorded (Cowes) are frequently adding to their specific yachting history collections. half-models of yachts and collected these in a database. Such models, often seen screwed to yacht clubhouse This list makes no claim to be comprehensive, and we have taken a decision not to include major walls, may be only quaint decoration to present-day national libraries, such as British, Scottish, Welsh, members of our Association, but these carefully crafted Trinity College (Dublin), Bodleian (Oxford), models are primary historical artefacts. -

View the Presentation

Presentation prepared for The Collectors Club New York The History of the Square-Rigged Sailing Vessels Jonas Hällström FRPSL 19 March 2014 The History of the Square-Sigged Sailing Vessels This booklet is the handout prepared for the presentation given to The Collectors Club in New York on 19 March 2014. Of 65 printed handouts this is number Presentation prepared for The Collectors Club The History of the Square-Rigged Sailing Vessels Jonas Hällström 19 March 2014 Thanks for inviting me! Jonas Hällström CCNY member since 2007 - 2 - The History of the Square-rigged Sailing Vessels 1988 First exhibited in Youth Class as Sailing Ships 2009 CHINA FIP Large Gold (95p) 2009 IBRA FEPA Large Gold (95p) 2010 JOBURG FIAP Large Gold (96p) 2010 ECTP FEPA Grand Prix ECTP 2013 AUSTRALIA FIP Large Gold (96p) European Championship for Thematic Philately Grand Prix 2010 in Paris The ”Development” (Story Line) as presented in the Introductory Statement (”Plan”) - 3 - Thematic The History of the Development Square-rigged Sailing Vessels The concept for this Storyline presentation (the slides) Thematic Information Thematic Philatelic item to be knowledge presented here Philatelic Information Philatelic knowledge The Collectors Club New York The legend about the The History of the sail and the Argonauts Square-rigged Sailing Vessels (introducing the story) The legend says that the idea about the sail on a boat came from ”The Papershell” (lat. Argonaute Argo). Mauritius 1969 The Collectors Club New York - 4 - The legend about the sail and the Argonauts (introducing the story) In Greek mythology it is said that the Argonauts sailed with the ship “Argo”. -

A.Y.R.S. PUBLICATION No. 7 SHEARWATER III in JIGS

A.Y.R.S. PUBLICATION No. 7 SHEARWATER III IN JIGS : - CONTENTS I. A.Y.R.S. Correspondents. 4. Indonesian Floats. - 2. "SHEARWATER III" 5. A Micronesian Canoe. : .• : 3. A Double Outrigger. 6. Catamaran Sail Balance, i... ..^ - 7. Letters. ; Price $1.00 Price 5/- A.V.R.S. I'lJlil.lCATlONS 1. Catamarans. ^ 4 18. Catamaran Developments. 2. Hydrofoils. \ - * 19. Hydrofoil Craft. 3. Sail Evolution. 20. Modern Boatbuilding . 4. Outriggers. Outriggers 5. Sailing Hull Design. 21. Ocean Cruising. 6. Outrigged Craft. 22. Catamarans 1958. 7. Catamaran Construction. 23. Outriggers 1958. 8. Dinghy Design. 24. Yacht Wind Tunnels. 9. Sails and Aerofoils. 25. Fibreglass. 10. American Catamarans. 26. Sail Rigs. 11. The Wishbone Rig. 27. Cruising Catamarans. 12. Amateur Research. 28. Catamarans 1959. 13. Self Steering. 29. Outriggers 1959. 14. Wingsails. 30. Tunnel and Tank. 15. Catamaran Design. 31. Sailing Theory. 16. Trimarans and 32. Sailboat Testing. 17. Commercial Sail. 33. Sails 1960. 34. Ocean Trimarans. .^7. Aerodynamics 1. 35. Catamatans 1961. .38. Catamarans 1961. 36. Floats Foils and Fluid 39. Trimarans 1961. Flows. 40. Yacht Research 1. Stihscriplions : £\r anniiiti lor wliicli one gets four publications and other privileges starting from January each year. We lia\ a wind tuimel where members can improve their sailing skill. Discussion Meetings are now being held in London and Sailing Meetings are being arranged. THE AMATEUR YACHT RESEARCH SOCIETY (Founded June, 195.S) Presidciils : Biitisli : American : New Zealand Lord lirahazon of Tara, Walter Hloemharii |. li. lirookc. G.ii.i:., M.c, r.c. Vice-I'residciils : ' " British: American: R. Ciresham Cooke, c.ii.i;., M. -

AMEE 2005 Abstracts

Abstracts AMEE 2005 in collaboration with Vrije Universiteit and the VU university medical center, Amsterdam Abstracts 30 August – 3 September 2005 RAI Congress Centre Amsterdam, The Netherlands Association for Medical Education in Europe Tay Park House, 484 Perth Road, Dundee DD2 1LR, Scotland, UK Tel: +44 (0)1382 631953 Fax: +44 (0)1382 631987 Email: [email protected] http://www.amee.org 1 INDEX OF ABSTRACTS Index of Abstracts Wednesday 31 August (blue section) Session 1 Plenary: What makes a good doctor? .. .. .. .. .. 7 Session 2 2AUD Symposium: Attitudes and professionalism .. .. .. .. 8 2A Symposium: Project GLOBE: A new initiative to provide quality CPD for Generalist Physicians .. 8 2B Short communications: Problem-based learning: the presenting problem .. .. 8 2C Short communications: Training for leadership .. .. .. .. 10 2D Short communications: Student characteristics .. .. .. .. 11 2E Short communications: Approaches to Multiprofessional education .. .. 13 2F Short communications: Methods of teaching and learning .. .. .. 14 2H Workshop: How to improve oral examinations in medical practice .. .. 16 2L Short communications: Selection for graduate entry to medicine .. .. 16 2M Short communications: Clinical assessment .. .. .. .. 17 2N Short communications: e-Learning: instructional design .. .. .. 19 2O Short communications: Continuing Professional Development/Continuing Medical Education 1 .. 20 2R Workshop: Emergency and Trauma management: training providers and instructors .. 22 2S Workshop: Active learning on the Web: how to develop an effective instructional web site .. 22 2T Workshop: Multi source (360 degree) feedback for assessment, feedback and learning across the medical education continuum .. .. .. .. 22 2U Workshop: Developing and using standardized video cases for computerized assessment of communication skills for pre-clinical medical students .. .. .. 22 2 Onyx 1 Posters: e-Learning in medical education . -

IT's a WINNER! Refl Ecting All That's Great About British Dinghy Sailing

ALeXAnDRA PALACe, LOnDOn 3-4 March 2012 IT'S A WINNER! Refl ecting all that's great about British dinghy sailing 1647 DS Guide (52).indd 1 24/01/2012 11:45 Y&Y AD_20_01-12_PDF.pdf 23/1/12 10:50:21 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K The latest evolution in Sailing Hikepant Technology. Silicon Liquid Seam: strongest, lightest & most flexible seams. D3O Technology: highest performance shock absorption, impact protection solutions. Untitled-12 1 23/01/2012 11:28 CONTENTS SHOW ATTRACTIONS 04 Talks, seminars, plus how to get to the show and where to eat – all you need to make the most out of your visit AN OLYMPICS AT HOME 10 Andy Rice speaks to Stephen ‘Sparky’ Parks about the plus and minus points for Britain's sailing team as they prepare for an Olympic Games on home waters SAIL FOR GOLD 17 How your club can get involved in celebrating the 2012 Olympics SHOW SHOPPING 19 A range of the kit and equipment on display photo: rya* photo: CLubS 23 Whether you are looking for your first club, are moving to another part of the country, or looking for a championship venue, there are plenty to choose WELCOME SHOW MAP enjoy what’s great about British dinghy sailing 26 Floor plans plus an A-Z of exhibitors at the 2012 RYA Volvo Dinghy Show SCHOOLS he RYA Volvo Dinghy Show The show features a host of exhibitors from 29 Places to learn, or improve returns for another year to the the latest hi-tech dinghies for the fast and your skills historical Alexandra Palace furious to the more traditional (and stable!) in London. -

Chapter 7 Rigging the Sail

1 Chapter 7 (..of The Cambered Panel Junk Rig...) Rigging the sail. (..all those ropes!) Malena, 1.4t, 32sqm Johanna, 3.2t, 48sqm Broremann 0.20t, 10sqm Frk. Sørensen, 0.74t, 20m2 Ingeborg, 2.15t, 35sqm In this chapter, I will mainly tell how I have rigged my own sails, but may also show alternative ways of doing it. Actually, I think it is a good idea to read this chapter before one settles on a rig type. No doubt, this text will have to be updated several times, as I receive more feedback. I will frequently use links to other write-ups I have produced, to describe details. Since all of these sit on the same website, they will stay operational for as long as this chapter does. If you are a serious doer, I guess it makes sense to download these texts and store them. One never knows when a website might fold... Aluminium mast cap (5mm thick) Webbing type mast cap for 10sqm sail on Broremann. Preparing the mast for first stepping. With the mast in hand, one needs some way of attaching the halyard etc. to the mast top. My preferred way has been to make some sort of mast cap of steel or (better) aluminium. For smaller rigs, I have just made it out of webbing and fixed it to the mast with a couple of hose clamps. In the latter case, one should add a fez-type cap to it, to protect the webbing from the sun. All my mast tops have been of wood. -

The Sailing Magazine for the Rest of Us

The sailing magazine for the rest of us. 10 00 00 $8 (Canada $8 CDN) 10 0 62825 97035 7 goodoldboat.com Issue 128 September/October 2019 Automatic/Manual Inflatable PFD USCG Approved Type V with Type II Performance! Full 35 lbs buoyancy! Comfortable, low profile, with wide neoprene neckline. Universal sizing, fits 30"-65" chest. Hi-Vis inflation chamber. Durable 400 denier nylon. Super bright retro-reflective areas on front and a high-visibility BEACON logo on the back. H Reg 179.99 HAMILTON SAVE $ 99 $30 NEW! 149 ea Pre-order MARINE Part# Color Order# ™ HMI-BCNI35OG Orange/Gray 773536 today! HMI-BCNI35BG Blue/Light Gray 773535 BOATERS' STORE! Moisture Absorber Dries air in cabins, lockers, closets, rooms, basements and other enclosed State-of-the-art line areas. Super-dry concentrated pellet of premium coatings, formula absorbs up to 50% more adhesives and putties. moisture than flake formulas. Search# SYT- $ 29 7 ea MK-6912 Order# 144114 Hamilton Wayne Photo by Tea Tree Power® Mold & Mildew Eliminator Non-toxic, bio-degradable. Blended from 100% Australian tea tree oil. Available in gel or spray. Tarps Starting At • Lightweight Blue 3 GRADES, $ 99 • Premium White 27 SIZES! 17 ea • Super Heavy Duty Silver HAMILTON Search# FOR-77020 Search# STT- Premium 7 Mil. White Oil Absorbent Sheets Shrink Wrap Each 15" x 19" sheet CAN HELP! absorbs 13 to 25 times Some sizes are available its weight in oil, fuel Many Hamilton Marine employees maintain in clear and blue. Shrink and other hydrocar- their own boats. And there is no better teacher wrap accessories are also bons. -

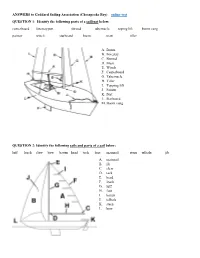

ANSWERS to Goddard Sailing Association

ANSWERS to Goddard Sailing Association (Chesapeake Bay) online-test QUESTION 1: Identify the following parts of a sailboat below: centerboard forestay port shroud tabernacle toping lift boom vang painter winch starboard boom mast tiller A. Boom B. Forestay C. Shroud D. Mast E. Winch F. Centerboard G. Tabernacle H. Tiller I. Topping lift J. Painter K. Port L. Starboard M. Boom vang QUESTION 2: Identify the following sails and parts of a sail below: luff leach clew bow batten head tack foot mainsail stern telltale jib A. mainsail B. jib C. clew D. tack E. head F. leach G. luff H. foot I. batten J. telltale K. stern L. bow QUESTION 3: Match the following items found on a sailboat with one of the functions listed below. mainsheet jibsheet(s) halyard(s) fairlead rudder winch cleat tiller A. Used to raise (hoist) the sails HALYARD B. Fitting used to tie off a line CLEAT C. Furthest forward on-deck fitting through which the jib sheet passes FAIRLEAD D. Controls the trim of the mainsail MAINSHEET E. Controls the angle of the rudder TILLER F. A device that provides mechanical advantage WINCH G. Controls the trim of the jib JIBSHEET H. The fin at the stern of the boat used for steering RUDDER QUESTION 4: Match the following items found on a sailboat with one of the functions listed below. stays shrouds telltales painter sheets boomvang boom topping lift outhaul downhaul/cunningham A. Lines for adjusting sail positions SHEETS B. Used to adjust the tension in the luff of the mainsail DOWNHAUL/CUNNINGHAM C. -

Jan 2 2016 Magazine Issue 37

www.classic-yacht.asn.au Issue 37 - January 2016 - Classic Yacht Association of Australia Magazine CONTENTS CYAA REPRESENTATIVES 2 NEW MEMBERS 2 COMING EVENTS 2 SAYONARA and RAWHITI 3 CUP REGATTA 2015 4 AUSTRALIAN HISTORIC 6 VESSELS REGISTER A MAN and HIS BOATS 8 AUSTRALIAN WOODEN 22 BOAT FESTIVAL ST. HELENA CUP REGATTA 28 MANLY WYNNUM YC Q’LD I BUILT A TUMLARE` FOR £350 32 CLASSIC YACHT FOR SALE 34 CYAA MEMBERSHIP 36 APPLICATION Our aim is to promote the appreciation and participation of sailing classic yachts in Australia, and help preserve the historic and cultural significance of these unique vessels. Classic Yacht Association of Australia CYAA REPRESENTATIVES NEW MEMBERS ADMINISTRATION Janet Dean Vic Crew Dingo CYAA Christopher Lawrence Vic Crew Snow Goose PO Box 335 Williamstown Geoff Thorn Vic Crew Martini Victoria 3016 Chris Havre Vic Boat owner Akuna admin@classic‑yacht.asn.au Charlie Boyes Vic Crew Martini QUEENSLAND Mal Botterill Vic Crew Avian Greg Doolan David Brodziak Vic Crew Ettrick Mobile 0418 12 12 02 [email protected] Peter Denniston Vic Boat owner Te Uira http://tradboatsqld.asn.au/ Chris Clapp Vic Crew Fair Winds Robert Kalkman Vic Boat owner Enterprise MAGAZINE EDITORIAL Tim Boucaut Vic Boat owner Warringa Peter Costolloe Deb McKay Vic Crew Warringa Mobile 0419 171 011 [email protected] Dennis Horne Vic Crew Warringa Sam Cowell Vic Crew Warringa Roger Dundas Mobile 0419 342 144 Sam Daniel Vic Crew Mercedes 111 [email protected] Doug McLean Vic Crew Tandanya Michael Daddo Vic Crew Mercedes 111 CYAA EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Noel Sutcliffe Vic Crew Trim President Martin Ryan Mercedes III COMING EVENTS Vice President Cameron Dorrough Bungoona Secretary Ian Rose Cyan 2016 Yanmar Wooden Boat Shop Wooden Boat Festival of Geelong.