KIRKLAND Handmade Aesthetics in Animation for Adults and Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aardman in Archive Exploring Digital Archival Research Through a History of Aardman Animations

Aardman in Archive Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Rebecca Adrian Aardman in Archive | Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Rebecca Adrian Aardman in Archive: Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Copyright © 2018 by Rebecca Adrian All rights reserved. Cover image: BTS19_rgb - TM &2005 DreamWorks Animation SKG and TM Aardman Animations Ltd. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Media and Performance Studies at Utrecht University. Author Rebecca A. E. E. Adrian Student number 4117379 Thesis supervisor Judith Keilbach Second reader Frank Kessler Date 17 August 2018 Contents Acknowledgements vi Abstract vii Introduction 1 1 // Stop-Motion Animation and Aardman 4 1.1 | Lack of Histories of Stop-Motion Animation and Aardman 4 1.2 | Marketing, Glocalisation and the Success of Aardman 7 1.3 | The Influence of the British Television Landscape 10 2 // Digital Archival Research 12 2.1 | Digital Surrogates in Archival Research 12 2.2 | Authenticity versus Accessibility 13 2.3 | Expanded Excavation and Search Limitations 14 2.4 | Prestige of Substance or Form 14 2.5 | Critical Engagement 15 3 // A History of Aardman in the British Television Landscape 18 3.1 | Aardman’s Origins and Children’s TV in the 1970s 18 3.1.1 | A Changing Attitude towards Television 19 3.2 | Animated Shorts and Channel 4 in the 1980s 20 3.2.1 | Broadcasting Act 1980 20 3.2.2 | Aardman and Channel -

2011-2012 (Pdf)

Trinity College Bulletin Catalog Issue 2011-2012 August 16, 2011 Trinity College 300 Summit Street Hartford, Connecticut 06106-3100 (860)297-2000 www.trincoll.edu Trinity College is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges, Inc NOTICE: The reader should take notice that while every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information provided herein, Trinity College reserves the right to make changes at any time without prior notice. The College provides the information herein solely for the convenience of the reader and, to the extent permissible by law, expressly disclaims any liability that may otherwise be incurred. Trinity College does not discriminate on the basis of age, race, color, religion, gender, sexual orientation, handicap, or national or ethnic origin in the administration of its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, and athletic and other College-administered pro- grams. Information on Trinity College graduation rates, disclosed in compliance with the Student Right- to-Know and Campus Security Act, Public Law 101-542, as amended, may be obtained by writing to the Office of the Registrar, Trinity College, 300 Summit Street, Hartford, CT 06106. In accordance with Connecticut Campus Safety Act 90-259, Trinity College maintains information concerning current security policies and procedures and other relevant statistics. Such information may be obtained from the director of campus safety at (860) 297-2222. Contents College Calendar 7 History of the College 10 The Mission of Trinity College 14 The Curriculum 15 The First-Year Program 16 Special Curricular Opportunities 17 The Individualized Degree Program 28 Graduate Studies 29 Advising 30 Requirements for the Bachelor's Degree 33 Admission to the College 43 College Expenses 49 Financial Aid 53 Key to Course Numbers and Credits 55 Distribution Requirement 57 Interdisciplinary Minors 58 African Studies................................................... -

Photo Journalism, Film and Animation

Syllabus – Photo Journalism, Films and Animation Photo Journalism: Photojournalism is a particular form of journalism (the collecting, editing, and presenting of news material for publication or broadcast) that employs images in order to tell a news story. It is now usually understood to refer only to still images, but in some cases the term also refers to video used in broadcast journalism. Photojournalism is distinguished from other close branches of photography (e.g., documentary photography, social documentary photography, street photography or celebrity photography) by complying with a rigid ethical framework which demands that the work be both honest and impartial whilst telling the story in strictly journalistic terms. Photojournalists create pictures that contribute to the news media, and help communities connect with one other. Photojournalists must be well informed and knowledgeable about events happening right outside their door. They deliver news in a creative format that is not only informative, but also entertaining. Need and importance, Timeliness The images have meaning in the context of a recently published record of events. Objectivity The situation implied by the images is a fair and accurate representation of the events they depict in both content and tone. Narrative The images combine with other news elements to make facts relatable to audiences. Like a writer, a photojournalist is a reporter, but he or she must often make decisions instantly and carry photographic equipment, often while exposed to significant obstacles (e.g., physical danger, weather, crowds, physical access). subject of photo picture sources, Photojournalists are able to enjoy a working environment that gets them out from behind a desk and into the world. -

Suggestions for Top 100 Family Films

SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS Title Cert Released Director 101 Dalmatians U 1961 Wolfgang Reitherman; Hamilton Luske; Clyde Geronimi Bee Movie U 2008 Steve Hickner, Simon J. Smith A Bug’s Life U 1998 John Lasseter A Christmas Carol PG 2009 Robert Zemeckis Aladdin U 1993 Ron Clements, John Musker Alice in Wonderland PG 2010 Tim Burton Annie U 1981 John Huston The Aristocats U 1970 Wolfgang Reitherman Babe U 1995 Chris Noonan Baby’s Day Out PG 1994 Patrick Read Johnson Back to the Future PG 1985 Robert Zemeckis Bambi U 1942 James Algar, Samuel Armstrong Beauty and the Beast U 1991 Gary Trousdale, Kirk Wise Bedknobs and Broomsticks U 1971 Robert Stevenson Beethoven U 1992 Brian Levant Black Beauty U 1994 Caroline Thompson Bolt PG 2008 Byron Howard, Chris Williams The Borrowers U 1997 Peter Hewitt Cars PG 2006 John Lasseter, Joe Ranft Charlie and The Chocolate Factory PG 2005 Tim Burton Charlotte’s Web U 2006 Gary Winick Chicken Little U 2005 Mark Dindal Chicken Run U 2000 Peter Lord, Nick Park Chitty Chitty Bang Bang U 1968 Ken Hughes Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, PG 2005 Adam Adamson the Witch and the Wardrobe Cinderella U 1950 Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson Despicable Me U 2010 Pierre Coffin, Chris Renaud Doctor Dolittle PG 1998 Betty Thomas Dumbo U 1941 Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Norman Ferguson Edward Scissorhands PG 1990 Tim Burton Escape to Witch Mountain U 1974 John Hough ET: The Extra-Terrestrial U 1982 Steven Spielberg Activity Link: Handling Data/Collecting Data 1 ©2011 Film Education SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS CONT.. -

2 a Quotation of Normality – the Family Myth 3 'C'mon Mum, Monday

Notes 2 A Quotation of Normality – The Family Myth 1 . A less obvious antecedent that The Simpsons benefitted directly and indirectly from was Hanna-Barbera’s Wait ‘til Your Father Gets Home (NBC 1972–1974). This was an attempt to exploit the ratings successes of Norman Lear’s stable of grittier 1970s’ US sitcoms, but as a stepping stone it is entirely noteworthy through its prioritisation of the suburban narrative over the fantastical (i.e., shows like The Flintstones , The Jetsons et al.). 2 . Nelvana was renowned for producing well-regarded production-line chil- dren’s animation throughout the 1980s. It was extended from the 1960s studio Laff-Arts, and formed in 1971 by Michael Hirsh, Patrick Loubert and Clive Smith. Its success was built on a portfolio of highly commercial TV animated work that did not conform to a ‘house-style’ and allowed for more creative practice in television and feature projects (Mazurkewich, 1999, pp. 104–115). 3 . The NBC US version recast Feeble with the voice of The Simpsons regular Hank Azaria, and the emphasis shifted to an American living in England. The show was pulled off the schedules after only three episodes for failing to connect with audiences (Bermam, 1999, para 3). 4 . Aardman’s Lab Animals (2002), planned originally for ITV, sought to make an ironic juxtaposition between the mistreatment of animals as material for scientific experiment and the direct commentary from the animals them- selves, which defines the show. It was quickly assessed as unsuitable for the family slot that it was intended for (Lane, 2003 p. -

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly June 2016

PROGRAMME THE DIVING BELL AND THE BUTTERFLY JUNE 2016 “possibly Britain’s most beautiful cinema..” (BBC) Britain’s Best Cinema – Guardian Film Awards 2014 JUNE 2016 • ISSUE 135 www.therexberkhamsted.com 01442 877759 Mon-Sat 10.30-6.30pm Sun 4.30-5.30pm BEST IN JUNE CONTENTS Films At A Glance 16-17 Rants and Pants 26-27 BOX OFFICE: 01442 877759 Mon to Sat 10.30-6.30 The Diving Bell and The Butterfly Sun 4.30-5.30 Remains one of our most powerful, beautiful films. (2008) Don’t miss. Page 18 SEAT PRICES Circle £9.00 FILMS OF THE MONTH Concessions £7.50 Table £11.00 Concessions £9.50 Royal Box Seat (Seats 6) £13.00 Whole Royal Box £73.00 All matinees £5, £6.50, £10 (box) Disabled and flat access: through SEE more. DO more. the gate on High Street (right of apartments) Truman Mustang 50% OFF YOUR SECOND PAIR A fabulous South American tragi- They’re saying this is the must-film Terms and conditions apply Director: James Hannaway comedy embracing all the worth in to see… so come and see. 01442 877999 life and death. Page 10 Page 13 Also available with Advertising: Chloe Butler 01442 877999 (From Space) Artwork: Demiurge Design 01296 668739 The Rex High Street (Three Close Lane) Berkhamsted, Herts HP4 2FG www.therexberkhamsted.com Troublemakers: Race The Story Of Land Art The timely story of Jesse Owens. “ Unhesitatingly The Rex Miss this and you might as well Hitler should have taken more 24 Bridge Street, Hemel Hempstead 25 Stoneycroft, Hemel Hempstead is the best cinema I have stop breathing… Breathtaking care of his skin. -

Module Und Lehrveranstaltungen Nach Semestern Ausführliche Fassung

Studium und Lehre Module und Lehrveranstaltungen nach Semestern Ausführliche Fassung WS 2012 Studiengang: BA Kun Stand: 26. Okt. 2012 - 18:55 Diese Liste enthält alle die den Modulen zugeordneten Lehrveranstaltungen des Studiengangs - geordnet nach Semestern in absteigender Reihenfolge und innerhalb eines Semesters nach Modulen. ab Seite Module und Lehrveranstaltungen im WS 2012 1 Module und Lehrveranstaltungen im SS 2012 26 Module und Lehrveranstaltungen im WS 2011 53 Module und Lehrveranstaltungen im SS 2011 72 Module und Lehrveranstaltungen im WS 2010 98 Module und Lehrveranstaltungen im SS 2010 121 Module und Lehrveranstaltungen im WS 2009 140 Module und Lehrveranstaltungen im SS 2009 167 Module und Lehrveranstaltungen im WS 2008 182 Module und Lehrveranstaltungen im SS 2008 198 Module und Lehrveranstaltungen im WS 2007 202 26.10.2012 18:55:09 Mod_VV_lang_INTEGR 1/207 Module und Lehrveranstaltungen im WS 2012 BA Kun KUG 101 # 01 BA Kun KUG 101 KUG101 Einführung in die Kunstgeschichte 6 LP O gültig für PO 2007-02-28 Fach/StR: H Fach/StR: N BA Kun KUG 101 # 01 S-3 Einführung in die kunsthistorischen Methoden 3 LP E. Leuschner Interpretationsübungen zur Kunstgeschichte bis ca 1800 (PO 2007:Einführung in die kunsthistorischen Methoden) Interpretation art history until 1800 WS 2012 3 05 0 021 ::38891:: •D• 16.10.2012 Di 18:00-20:00 LG 3/HS 112 In diesem Kurs sollen die Studierenden durch mündliche Beiträge oder selbstverfasste Kurztexte Methodenwissen für das Beschreiben und Interpretieren von Kunstwerken des in KUG 101#01 behandelten Zeitraums nach Kriteren wie Material, Stil, Aussage/Bedeutung und kulturelle Kontexte erwerben. In this course, students will develop and sharpen their interpretative skills by describing and analysing works of art from the period covered by course KUG 101#01 according to criteria such as artistic technique, style, meaning and cultural contexts. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

List Article – Top 3 Best Adult Animated Series on Television For

List Article – Top 3 Best Adult Animated Series On Television For a few decades, cartoons were only for children. Either they were filled with kid-friendly story lines or they were “PC” enough that everyone could enjoy them. What a terrible world... Luckily, something fantastic occurred in the late 80’s: adult animation went mainstream. All of a sudden, it was cool to be in college and watching cartoons. Sometimes the shows were good, other times they were odd and still others were just plain terrible. After 25 years, tons of shows have come and gone, with only a few standing out as the best of the best. Here are my top 3 adult animated series of all time: 3) Family Guy By the late 1990’s when we thought we had seen in all, Seth MacFarlane arrived. After a few years of animating children’s cartoons, Seth brought to the table one of the raunchiest, most terrible and insulting programs we had ever seen. Family Guy is the 3rd best adult cartoon in history. Another record-breaking series from Fox, the show centers on the Griffin family from Rhode Island. Peter (the idiot), Lois (the sane one), Chris (the Peter-in-training), Meg (the ugly one) and baby Stewie (the evil one), along with the family dog, Brian (the pretentious one) spend their days living lives of greed, lust, violence and every other major sin known to man. Every episode is filled with hilarious moments, mainly from the flashback cutaways, which have now become a standard in all animation. -

Known Nursery Rhymes Residencies Fruit Eaten Remembered World

13 Nov. 1995 – Leah Betts in coma after taking ecstasy 26 Sep. 2007 – Myanmar government, using extreme force, cracks down on protests Blockbusters Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1982 Pratchett, T. – Soul Music Celery Hilden, Linda The Tortoise and the Eagle Beverly Hills Cop Goodfellas Speed Peanut Brittle Dial M for Murder Russ Abbott Arena Coast To Coast Gary Numan Live Rammstein Vast Ready to Rumble (Dreamcast) Known Nursery Rhymes 22 Nov. 1995 – Rosemary West sentenced to life imprisonment 06 Oct. 2007 – Musharraf breezes to easy re-election in Pakistan Buckaroo Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1984 Pratchett, T. - Sorcery Chard Hill, Debbie The Jackdaw and the Fox Beverly Hills Cop 2 The Goonies Speed 2 Pear Drops Dinnerladies The Ruth Rendell Mysteries Aretha Franklin Cochine Gene McDaniels The Living End Ramones Vegastones Resident Evil (Various) All Around the Mulberry Bush 14 Dec. 1995 – Bosnia peace accord 05 Nov. 2007 – Thousands of lawyers take to the streets to protest the state of emergency rule in Pakistan. Chess Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1985 Pratchett, T. – The Streets of Ankh-Morpork Chickpea Hiscock, Anna-Marie The Boy and the Wolf Bicentennial Man The Good, The Bad and the Ugly Spider Man Picnic Doctor Who The Saint Armand Van Helden Cockney Rebel Gene Pitney Lizzy Mercier Descloux Randy Crawford The Velvet Underground Robocop (Commodore 64) As I Was Going to St. Ives 02 Jan. 1996 – US Peacekeepers enter Bosnia 09 Nov. 2007 – Police barricade the city of Rawalpindi where opposition leader Benazir Bhutto plans a protest Chinese Checkers Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1988 Pratchett, T. -

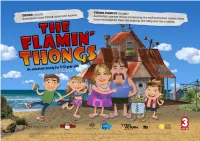

An Animated Comedy for 8-12 Year Olds 26 X 12Min SERIES

An animated comedy for 8-12 year olds 26 x 12min SERIES © 2014 MWP-RDB Thongs Pty Ltd, Media World Holdings Pty Ltd, Red Dog Bites Pty Ltd, Screen Australia, Film Victoria and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Whale Bay isis homehome toto thethe disaster-pronedisaster-prone ThongThong familyfamily andand toto Australia’sAustralia’s leastleast visitedvisited touristtourist attraction,attraction, thethe GiantGiant Thong.Thong. ButBut thatthat maymay bebe about to change, for all the wrong reasons... Series Synopsis ........................................................................3 Holden Character Guide....................................................4 Narelle Character Guide .................................................5 Trevor Character Guide....................................................6 Brenda Character Guide ..................................................7 Rerp/Kevin/Weedy Guide.................................................8 Voice Cast.................................................................................9 ...because it’s also home to Holden Thong, a 12-year-old with a wild imagination Creators ...................................................................................12 and ability to construct amazing gadgets from recycled scrap. Holden’s father Director’s‘ Statement..........................................................13 Trevor is determined to put Whale Bay on the map, any map. Trevor’s hare-brained tourist-attracting schemes, combined with Holden’s ill-conceived contraptions,