2011-2012 (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downtown Development Plan

Chapter 7 One City, One Plan Downtown Development Plan KEY TOPICS Downtown Vision Hartford 2010 Downtown Goals Front Street Downtown North Market Segments Proposed Developments Commercial Market Entertainment Culture Regional Connectivity Goals & Objectives Adopted June 3, 2010 One City, One Plan– POCD 2020 7- 2 recent additions into the downtown include the Introduction Downtown Plan relocation of Capitol Community College to the Recently many American cities have seen a former G. Fox building, development in the movement of people, particularly young profes- Adriaen’s Landing project area, including the sionals and empty nesters, back into down- Connecticut Convention Center and the towns. Vibrant urban settings with a mix of uses Connecticut Center for Science and Exploration, that afford residents opportunities for employ- Morgan St. Garage, Hartford Marriott Down- ment, residential living, entertainment, culture town Hotel, and the construction of the Public and regional connectivity in a compact pedes- Safety Complex. trian-friendly setting are attractive to residents. Hartford’s Downtown is complex in terms of Downtowns like Hartford offer access to enter- land use, having a mix of uses both horizontally tainment, bars, restaurants, and cultural venues and vertically. The overall land use distribution unlike their suburban counterparts. includes a mix of institutional (24%), commercial The purpose of this chapter is to address the (18%), open space (7%), residential (3%), vacant Downtown’s current conditions and begin to land (7%), and transportation (41%). This mix of frame a comprehensive vision of the Downtown’s different uses has given Downtown Hartford the future. It will also serve to update the existing vibrant character befitting the center of a major Downtown Plan which was adopted in 1998. -

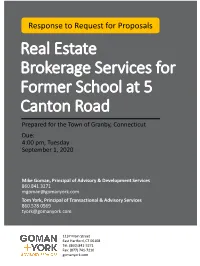

RFP Response

Response to Request for Proposals Real Estate Brokerage Services for Former School at 5 Canton Road Prepared for the Town of Granby, Connecticut Due: 4:00 pm, Tuesday September 1, 2020 Mike Goman, Principal of Advisory & Development Services 860.841.3271 [email protected] Tom York, Principal of Transactional & Advisory Services 860.528.0569 [email protected] 1137 Main Street East Hartford, CT 06108 Tel: (860) 841-3271 Fax: (877) 741-7210 gomanyork.com Table of Contents Letter of Transmittal 2 Company Overview and Project Approach 4 Site and Market Overview 9 Proposed Scope of Services 13 Team Qualifications 22 Leasing Capabilities 29 Relevant Experience 33 Fee Proposal 47 References 51 Certifications and Other Relevant Documents 53 RFP - Real Estate Broker Services for Former School at 5 Canton Rd 1 Former “Frank M. Kearns” primary school brokerage services Transmittal Letter September 1, 2020 Ms. Abigail Kenyon Director of Community Development Town of Granby 15 North Granby Rd Granby CT 06035 Re: Real Estate Services RFP Dear Ms. Kenyon, We recognize the challenges facing smaller communities and focus on creating actionable plans to adaptively reuse functionally obsolete properties. Preserving and building upon history requires a consultant who is aware of the local and regional sensibilities of the stakeholders and who will approach the assignment with the necessary awareness and integrity to support the Town’s mission of promoting economic development. Our primary role will be to assist the Town of Granby in the development, management and implementation of a Strategic Marketing Campaign for the former Frank M. Kearns primary school property located at 5 Canton Road. -

Photo Journalism, Film and Animation

Syllabus – Photo Journalism, Films and Animation Photo Journalism: Photojournalism is a particular form of journalism (the collecting, editing, and presenting of news material for publication or broadcast) that employs images in order to tell a news story. It is now usually understood to refer only to still images, but in some cases the term also refers to video used in broadcast journalism. Photojournalism is distinguished from other close branches of photography (e.g., documentary photography, social documentary photography, street photography or celebrity photography) by complying with a rigid ethical framework which demands that the work be both honest and impartial whilst telling the story in strictly journalistic terms. Photojournalists create pictures that contribute to the news media, and help communities connect with one other. Photojournalists must be well informed and knowledgeable about events happening right outside their door. They deliver news in a creative format that is not only informative, but also entertaining. Need and importance, Timeliness The images have meaning in the context of a recently published record of events. Objectivity The situation implied by the images is a fair and accurate representation of the events they depict in both content and tone. Narrative The images combine with other news elements to make facts relatable to audiences. Like a writer, a photojournalist is a reporter, but he or she must often make decisions instantly and carry photographic equipment, often while exposed to significant obstacles (e.g., physical danger, weather, crowds, physical access). subject of photo picture sources, Photojournalists are able to enjoy a working environment that gets them out from behind a desk and into the world. -

![CRB 2002 Report [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0594/crb-2002-report-pdf-250594.webp)

CRB 2002 Report [Pdf]

Motion Picture Production in California By Martha Jones, Ph.D. Requested by Assembly Member Dario Frommer, Chair of the Select Committee on the Future of California’s Film Industry MARCH 2002 CRB 02-001 Motion Picture Production in California By Martha Jones, Ph.D. ISBN 1-58703-148-5 Acknowledgements Many people provided assistance in preparing a paper such as this, but several deserve special mention. Trina Dangberg helped immensely in the production of this report. Judy Hust and Roz Dick provided excellent editing support. Library assistance from the Information Services Unit of the California Research Bureau is gratefully acknowledged, especially John Cornelison, Steven DeBry, and Daniel Mitchell. Note from the Author An earlier version of this document was first presented at a roundtable discussion, Film and Television Production: California’s Role in the 21st Century, held in Burbank, California on February 1, 2002, and hosted by Assembly Member Dario Frommer. Roundtable participants included the Entertainment Industry Development Corporation (EIDC), The Creative Coalition (TCC) and the Screen Actors Guild (SAG). Assembly Member Frommer is chair of the Select Committee on the Future of California’s Film Industry. This is a revised version of the report. Internet Access This paper is also available through the Internet at the California State Library’s home page (www.library.ca.gov) under CRB Reports. Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................. 1 I. OVERVIEW OF THE CALIFORNIA MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY............ 5 SIZE AND GROWTH OF THE CALIFORNIA MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY ............................ 5 The Motion Picture Industry Measured by the Value of Output During the 1990s.... 5 The Motion Picture Industry Measured by Employment ........................................... -

Media Arts Design 1

Media Arts Design 1 • Storyboarding Certificate (https://catalog.nocccd.edu/cypress- MEDIA ARTS DESIGN college/degrees-certificates/media-arts-design/storyboarding- certificate/) Division: Fine Arts Courses Division Dean MAD 100 C Introduction to Media Arts Design 3 Units Dr. Katy Realista Term hours: 36 lecture and 72 laboratory. This course focuses on the use of digital design, video, animation and page layout programs. This course Faculty is designed for artists to design, create, manipulate and export graphic Katalin Angelov imagery including print, video and motion design elements. This course is Edward Giardina intended as a gateway into the varied offerings of the Media Arts Design program, where the student can pursue more in-depth study on the topic(s) Counselors that most attracted them during this introductory class. $20 materials fee payable at registration. (CSU, C-ID: ARTS 250) Renay Laguana-Ferinac MAD 102 C Introduction to WEB Design (formerly Introduction to WEB Renee Ssensalo Graphics-Mac) 3 Units Term hours: 36 lecture and 72 laboratory. This course is an overview of the Degrees and Certificates many uses of media arts design, with an emphasis on web publishing for • 2D Animation Certificate (https://catalog.nocccd.edu/cypress- the Internet. In the course of the semester, students create a personal web college/degrees-certificates/media-arts-design/associate-in-science- page enriched with such audiovisual elements as animation, sound, video in-film-television-and-electronic-media-for-transfer-degree/) and different types of still images. This course is intended as a gateway into • 3D Animation Certificate (https://catalog.nocccd.edu/cypress- the varied offerings of the Media Arts Design program, where the student college/degrees-certificates/media-arts-design/3d-animation- can pursue more in-depth study on the topics that most attracted them certificate/) during this introductory class. -

Nursing for Hartford Hospital Nurses and Alumnae of the Hartford Hospital School of Nursing

Spring 2019 Nursing For Hartford Hospital nurses and alumnae of the Hartford Hospital School of Nursing Michaela Gaudet, BSN, RN Sonia Perez, BSN, RN Contents Hartford Hospital’s 1 Messages From Executive Leadership Nursing Professional 2 The ART And ETHICS Of Nursing New Program Expands Opportunities Practice Model For Bedside Nurses 3 The SCIENCE Of Nursing Wound Care: Providing Opportunities For Nurses And The Best Patient Care 4 The ART Of Nursing Roxana Murillo: At The Bedside Is Where This Nurse Wants To Be 5 Nurturing Happier, Better Skilled, And More Confident Nurses 6 The ADVOCACY Of Nursing Melissa Hernandez-Smythe: An Empowered Nurse Who’s Now Empowering Others 8 The SCIENCE Of Nursing Michaela Lis: Advancing Trauma Care As She Advances Her Career 10 The ART And ADVOCACY Of Nursing Mike Gilgenbach & Jamie Houle: From Entry-Level Staff To Leaders In Nursing 12 The SCIENCE And ETHICS Of Nursing Ann Russell: From Giving The Best Care To Now Helping Develop It 13 Nursing News & Notes 15 Nightingale Awards 16 A Message From The President Of The Alumnae Association The Nursing Professional Practice Model was 17 Alumnae Spotlight: Every Day, She Uses The Love Of Learning That HHSN Instilled developed by nurses from across Hartford 18 A Look Back: She Was Part Of ‘The Greatest Hospital. It is a visual representation of the Generation’ scope of nursing practice and nursing’s role 19 The PILLBOX Alumnae News in enhancing the human health experience. News And Photos From Our Graduates 21 Alumnae Comments 21 In Memoriam Advisory Board -

Heidi Ellis Vita

Curriculum Vitae Heidi J. C. Ellis Computer Science Department Trinity College 300 Summit St. Hartford, CT 06106 (860) 297-4175, fax: (860) 297-3531 [email protected] http://www.cs.trincoll.edu/~hellis2 Education Ph.D., Computer Science and Engineering, University of Connecticut, 1994 Dissertation: An Information Engineering Approach to Unified Object-Oriented Design and Analyses M.S., Computer Science and Engineering, University of Connecticut, 1990 B.S., Animal Science, University of Connecticut, 1984 Experience Professional Experience 2005-present, Visiting Assistant Professor, Dept. of Computer Science, Trinity College 2000-2005, Associate Professor, Dept. of Engineering and Science, RPI-Hartford 1997-2000, Assistant Professor, Computer and Information Sciences, RPI-Hartford 1996-1997, Assistant Professor, Computer Science, Hartford Graduate Center 1994-1996, Visiting Assistant Professor, Computer Science, Hartford Graduate Center 1990, 1992, 1993, Lecturer, Computer Science and Engineering, University of Connecticut 1990-1991, Adjunct Assistant Professor, Dept. of Math and Computer Science, Eastern Connecticut State University 1987-1994, Research Assistant, Computer Science and Engineering, University of Connecticut Industrial Experience MassMutual Financial Group, Springfield, MA. Responsible for identifying and carrying out training and mentoring needs required for converting an eight-person department from a procedure-based to an object oriented development approach. Tasks included software process audit, software process needs assessment, development mentoring and object oriented training. Jan. 2000 to Jun. 2000. Pratt & Whitney, East Hartford, CT. Observed the Embedded Systems group, specifically the software process used to develop the embedded software that operates jet engines. Observed FAA’s DO-178A and DO-178B certification process and its impact on software development. -

Program and Course Guide 2016 | 2017 Red Deer College

PROGRAM AND COURSE GUIDE 2016 | 2017 RED DEER COLLEGE program and course guide 2016 - 2017 learning philosophy Our commitment to learners and learning is at the heart of Red Deer College and this is reflected in our values of accountability, inclusiveness, exploration, excellence, integrity and community. We believe in fostering intellectually rigorous, professionally relevant, and dynamic learning environments of inquiry, exploration, application and creativity. We ensure accessibility to multiple pathways of formal and informal learning through active engagement, facilitated learning processes, and scholarly excellence. We value learning because it empowers our learners to be highly productive in the work force and within our communities. We honour the intrinsic value of learning in supporting self development, growth and fulfillment in the individual learner. We promote positive lifelong learning habits and attitudes that embrace local, national, and global experiences, issues and perspectives. www.rdc.ab.ca Contents Table of Contents . 2 B.Sc. in Agriculture . 58 Management Certificate . 102 President’s Message . 3 B.Sc. in Agriculture Mechanical Engineering Technology . 104 Academic Schedule 2016-2018 . 4 Food Business Management . 59 Medical Lab Assistant . 105 Admission . 8 B.Sc. in Atmospheric Sciences . 60 Motion Picture Arts . 106 Fees . 12 B.Sc. in Biochemistry . 60 Music . 107 Prior Learning Assessment . 13 B.Sc. in Biological Sciences . 61 Occupational Therapist & B.Sc. in Chemistry . 62 Physiotherapist Assistant . 111 Degree Completion Programs: B.Sc. in Engineering . 63 Open Studies . 112 B.Sc. in Environmental Pharmacy Technician . 113 Red Deer College Applied Degree in & Conservation Sciences . 65 Practical Nurse . 114 Motion Picture Arts . 16 B.Sc. Environmental Science or Social Work . -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

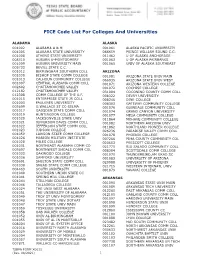

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

The Economics of Film

1127 - 09/20 Doc Title The Economics of Film B - Front Page one line title ARTICLE The Economics of Film Changing dynamics and the COVID-19 world In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the feature film industry at every level, bringing content production to a standstill and cancelling cinema premieres. Worldwide, cinemas were shuttered and in turn, film goers forced to stay at home, eyeing old and new televisual content to fill the entertainment void. In the intervening time, the major studios, led by (1) The Economics of Film Universal, began to explore ways of reaching their Traditional economics of film – flow of money audiences through direct and digital alternatives. Without out-of-home entertainment (except drive-in cinemas), Film studios are all too aware of how important theatrical the shuttered cinemas closed off a significant distribution cinema release is to generating income and contributing and income avenue for the studios. Moreover, the to the profitability of creating, producing, marketing and major studios with their newly created digital streaming distributing a film. platforms – Peacock, Disney+ and Warner’s HBO Max – Chart 1 (below) shows the costs and revenue associated were poised and equipped to offer an alternative. with a big budget film. Studios receive on average 40% – And, they did. 50% of the total film revenues from the theatrical cinema This article considers three critical areas for the film window, by a long chalk the largest and most significant industry: (1) the current economics of film production and contributor to income. The remaining percentages the significance of cinema theatre contribution within of income generated downstream are across several the film supply chain; (2) historical worldwide box office categories of revenues, including: (i) first and second returns generated through the cinema distribution window cycle TV, (ii) home video, (iii) merchandise, and (iv) and how that compares to the potential income from on demand, pay-per-view. -

Re-Opening Higher Education Update from Ct

RE-OPENING HIGHER EDUCATION UPDATE FROM CT INDEPENDENT COLLEGES MARC CAMILLE, PRESIDENT, ALBERTUS MAGNUS JUDY OLIAN, PRESIDENT, QUINNIPIAC UNIVERSITY JENNIFER WIDNESS, PRESIDENT, CCIC 1 CCIC MEMBER COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES • Albertus Magnus College • Trinity College • Connecticut College • University of Bridgeport • Fairfield University • University of Hartford • Goodwin University • University of New Haven • Mitchell College • University of Saint Joseph • Quinnipiac University • Wesleyan University • Rensselaer at Hartford • Yale University • Sacred Heart University 2 INDEPENDENT COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES IN CT • Awarded 53% of higher ed degrees in CT in 2019, compared to 43% awarded by public institutions • Educate 49% of students of color attending 4-year institutions in CT • Award 71% of computer science degrees in the State • Award 66% of the degrees in the health professions • Award 62% of the engineering degrees in the State • Award 48% of biological and biomedical degrees in CT • Completion rates are 10% higher than in public institutions overall; 16% higher for BlacK students, and 26% higher for LatinX students • Educate economically challenged students – 24% are Pell grant recipients, compared to 31% in public colleges • Over $33 B in total economic impact annually in the State of CT • In several cases, these colleges and universities are THE driver of the economic activity in the town, and are the largest employer • Over 220,000 graduates of the CCIC schools reside in CT THIS SECTOR IS VITAL TO THE ECONOMIC AND CIVIC FUTURE