View a Transcript of This Podcast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Life and Stryper Revealed

HONESTLY My life and Stryper revealed. By Michael Sweet Founding member, singer, songwriter, and guitarist of the pioneering Christian rock band Stryper tells his life story…. Honestly. with Dave Rose and Doug Van Pelt © 2014 Big3 Records ONE I drink. Occasionally I smoke. If you ask my wife, my kids, my tech, my agent or my manager they'll all tell you that I curse more than I should. I've fooled around with women on tour buses. I’ve been arrested for indecent exposure. I've been reckless with money to the point of bankruptcy. My favorite bands are The Beatles, Van Halen and Judas Priest. I was pissed at God when my wife died of cancer and I despise religion. I am a Christian. I'm Michael Sweet. I’m a singer, guitarist, songwriter, producer and a founding member of the pioneering Christian rock band Stryper. We've sold almost 10 million records to date and were the first Christian band to air on MTV, and to have four #1 videos. We even had two top-10 videos at the same time, back when MTV actually played music videos. We've played soccer stadiums and biker bars, sometimes in the same week. Despite having done all of that, I'm still often known as the Bible-Tossing- Yellow & Black-Bumble-Bee guy. The Jesus guy. The 80's hair/glam Christian metal guy. An irrelevant joke. Or, even worse-- sometimes I'm not known at all. So who am I? I'm a guy that grew up in Southern California – sort of a surf punk kind of guy who absolutely loved music. -

Taters Versus Sliders: Evidence for A

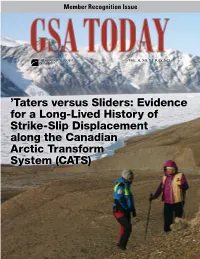

Member Recognition Issue VOL. 31, NO. 7 | J U LY 2 021 ’Taters versus Sliders: Evidence for a Long-Lived History of Strike-Slip Displacement along the Canadian Arctic Transform System (CATS) EXPAND YOUR LIBRARY with GSA E-books The GSA Store offers hundreds of e-books, most of which are only $9.99. These include: • popular field guides and maps; Special Paper 413 • out-of-print books on prominent topics; and Earth and • discontinued series, such as Engineering How GeologistsMind: Think Geology Case Histories, Reviews in and Learn about the Earth Engineering Geology, and the Decade of North American Geology. Each book is available as a PDF, including plates and supplemental material. Popular topics include ophiolites, the Hell Creek Formation, mass extinctions, and plates and plumes. edited by Cathryn A. Manduca and David W. Mogk Shop now at https://rock.geosociety.org/store/. JULY 2021 | VOLUME 31, NUMBER 7 SCIENCE 4 ’Taters versus Sliders: Evidence for a Long- Lived History of Strike Slip Displacement along the Canadian Arctic Transform System (CATS) GSA TODAY (ISSN 1052-5173 USPS 0456-530) prints news and information for more than 22,000 GSA member readers William C. McClelland et al. and subscribing libraries, with 11 monthly issues (March- April is a combined issue). GSA TODAY is published by The Geological Society of America® Inc. (GSA) with offices at Cover: Geologists studying structures along the Petersen Bay 3300 Penrose Place, Boulder, Colorado, USA, and a mail- fault, a segment of the Canadian Arctic transform system (CATS), ing address of P.O. Box 9140, Boulder, CO 80301-9140, USA. -

Students Accountable to Students

Members of a group consider themselves mostly account- able to an external authority, while members of a team 2 also hold themselves and each other accountable. In moments of contribution and accountability, discussions of course material in the TBL classroom acquire a remarkable emotional charge. The Social Foundation of Team-Based Learning: Students Accountable to Students Michael Sweet, Laura M. Pelton-Sweet When I was taking science here at Harvard, it was awfully intim- idating at times, and . it was just lonely. You’re sort of in your own world. I didn’t know the student’s name to my left. I didn’t know the student’s name to my right. That’s really disconcerting. Eric Chehab, Harvard student (Derek Bok Center, 1992) No man is an island. John Donne The human need for a sense of belonging is deep and powerful and has been explored by scholars as prominent as Freud (1922), Festinger (1954), and Schutz (1958), among many others. Following Tinto’s book Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition (1987), many began investigating the extent to which a college student’s sense of social connec- tion in the classroom affects variables like academic performance, self- efficacy, motivation to learn, and perceptions of one’s instructor, peers, and task value (Booker, 2008; Freeman, Anderman, and Jensen, 2007; Pittman and Richmond, 2007; Summers, Beretvas, Svinicki, and Gorin, 2005). Given this growing understanding of the social dimension of the class- room, it is no surprise that positive emotional and motivational effects of NEW DIRECTIONS FOR TEACHING AND LEARNING, no. -

Christian Heavy Metal Music, “Family Values,” and Youth Culture, 1984–1994

Metal Missionaries to the Nation | 103 Metal Missionaries to the Nation: Christian Heavy Metal Music, “Family Values,” and Youth Culture, 1984–1994 Eileen Luhr n June 26, 1987, members of the Christian metal band Stryken attended a Motley Crüe concert in San Antonio, Texas. It was not Ouncommon for Christian bands to attend secular concerts; indeed, many bands explained that they did so in order to keep current on musical trends. But Stryken arrived at the show ready for confrontation. According to the Christian metal magazine White Throne, the band, “wearing full suits of armor . and bearing a 14 x 8 foot wooden cross,” “stormed the doors of the arena, pushing through the crowds of teenagers and television cameras down the corridor towards the inlet to the main stage.” At this point, the “boys in armor” erected the cross and “began to preach to the massed [sic] of kids who were gathering all around.” The authorities quickly intervened, and, “ordered to remove ‘the cross’ or face arrest, the members of Stryken continued to speak openly about Jesus Christ, and were one by one hand-cuffed and forcibly removed from the arena.”1 Stryken’s actions—which invoked the persecuted early Christians described in the Acts of the Apostles—offer some insights into Christian metal during the 1980s. Motley Crüe’s music and the lifestyle of its members were designed to shock middle America, but the band had become one of the most successful acts of the 1980s. By upstaging Motley Crüe’s over-the-top behavior with their bold act, Stryken attempted to claim heavy metal’s reputation for outrageousness for Christianity. -

Download Honestly: My Life and Stryper Revealed Free Ebook

HONESTLY: MY LIFE AND STRYPER REVEALED DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Michael Sweet, Dave Rose, Doug Van Pelt | 286 pages | 06 May 2014 | Big3 Records | 9780996041805 | English | none Michael Sweet – "I’m Not Your Suicide": Hard Rock Daddy Review This might have something to do with the acoustics of the venue. For me, the best times musically came during the seventies and eighties. Robert: Brian is also an amazing guitar player, as well as a drummer. AXS: Stryper recently kicked off the U. Newer Posts Older Honestly: My Life and Stryper Revealed Home. While Stryper gambled on a more polished sound in and met with limited success, will this gamble on harder sounding album 30 years later be more successful? It exploded, had five number ones and made the cover of CCM Magazine, but at the same time, the label was hurting, and by the time I did Real, they were getting ready to close their doors. It was short lived, but they're very nice people and we get to see them over and over again…Blissed was a wonderful time re-vamping myself and coming alive again in the early s. Was that the Honestly: My Life and Stryper Revealed process you used for God Damn Evil? Why so Honestly: My Life and Stryper Revealed people have declared Michael Sweet a significant influence on their lives; from Larry the Cable Guy to professional wrestler Chris Jericho to Haitian musician and politician Wyclef Jean and more. Share on Facebook. The guitarist The first Christian rock band to see chart-topping success on MTV, Stryper went on to see over 10 million albums and has sold out arenas all over the world. -

A Banda "STRYPER"

PARTITURA PARA BATERIA DE: Por: Anderson Cleiton Rodrigues “CALLING ON ” 02/2013 BATERA CENTER- SBO/SP. A banda "STRYPER" A banda cristã Stryper, foi formada em 1983 pelos irmãos Michael (vocalista) e Robert Sweet (baterista) e os amigos Oz Fox (guitarrista) e Timothy Gaines (baixista, tecladista), no condado de Orange, Califórnia, E.U .A . É considerada a pioneira do gênero “Metal Cristão”. O nome “Stryper”, é referência a palavra “stripes”, do verso 5 Do capítulo 53 do livro Bíblico de Isaías. " stripes" significa "ferida", ou seja, as marcas causadas pela flagelação que Jesus Cristo viria a sofrer. Discografia: The Yellow and Black Attack (EP 1983), Soldiers Under Command (1985), The Yellow and Black Attack (1986), To Hell with the Devil (1986), In God We Trust (1988), Against the Law (1990), Can’t Stop the Rock (1991), Seven, The Best of Stryper (2003), 7 Weeks: Live in America (2003), Rebom (2005), The Roxx Regime Demos (2007), Murder by Pride (2009), The Covering (2011). Membros Atuais: Michael Sweet (vocal e guitarra), O z Fox (guitarra), Tracy Ferrie, e Timothy Gaines (baixo), Robert Sweet (bateria). Álbum “To hell with the devil” (1986) A música “CALLING ON" A canção pertence ao álbum "To hell with the devil" de 1986, o quarto da banda. Esse disco é considerado o melhor trabalho da banda e do genêro white metal em geral se tornando o ápice musical e comercial do Strype, ficando entre os top 40 da bilboard (algo então inédito para uma banda de white metal) e recebendo indicações para o Grammy. Baterista: Robert Sweet O baterista “ROBERT SWEET” Robert Sweet Lee nasceu em 21 de Março de 1960, Lynwood, Califórnia, E.U .A ., é baterista e produtor, e vocalista, no Stryper dês de 1984 até o momento. -

Student Accountability in Team-Based Learning Classes

TSOXXX10.1177/0092055X15603429Teaching SociologyStein et al. 603429research-article2015 Article Teaching Sociology 2016, Vol. 44(1) 28 –38 Student Accountability in © American Sociological Association 2015 DOI: 10.1177/0092055X15603429 Team-based Learning Classes ts.sagepub.com Rachel E. Stein1, Corey J. Colyer1, and Jason Manning1 Abstract Team-based learning (TBL) is a form of small-group learning that assumes stable teams promote accountability. Teamwork promotes communication among members; application exercises promote active learning. Students must prepare for each class; failure to do so harms their team’s performance. Therefore, TBL promotes accountability. As part of the course grade, students assess the performance of their teammates. The evaluation forces students to rank their teammates and to provide rationale for the highest and lowest rankings. These evaluations provide rich data on small-group dynamics. In this paper, we analyze 211 student teammate assessments. We find evidence that teams consistently give the lowest evaluations to their least involved members, suggesting that the team component increases accountability, which can promote learning. From these findings we draw implications about small-group dynamics in general and the pedagogy of TBL in particular. Keywords team-based learning, small-group learning, accountability In the past few decades, pedagogical researchers include properly formed and managed groups, have explored the effectiveness of small-group accountability for the quality of students’ work, learning in the classroom. Such research empha- frequent and timely feedback, and group assign- sizes the role of small groups in fostering active ments to promote learning and team development learning and argues that active learning is the most (Michaelsen 2004; Michaelsen and Sweet 2008). -

Without a Doubt, Stryper Is One of the Top Christian Rock Bands of All-Time, and Certainly the Most Celebrated Christian Metal Band of All Time

Without a doubt, Stryper is one of the top Christian rock bands of all-time, and certainly the most celebrated Christian metal band of all time. Comprised of Michael Sweet (vocals/guitar), Oz Fox (guitar), Tim Gaines (bass), and Robert Sweet (drums), Stryper has been rocking since 1983, and is responsible for such '80s metal classic albums as 'Soldiers Under Command,' 'To Hell with the Devil,' In God We Trust,' and such MTV hit singles/videos as "Calling on You," "Free," and "Honestly." After a sabbatical for much of the 1990's, Stryper returned strong in the early 21st century. But it was not until their 2011 covers set, 'The Covering,' that the aforementioned definitive Stryper was reinstated, as the band welcomed Gaines back into the fold. "Tim is an original member, so there's a certain magic and chemistry that you have with the original line-up, that you can't replace with someone else," explains Michael Sweet. "It's just there, it is what it is. And Tim brings that to the band. He's a very talented bass player, singer, and keyboard player. He brings a certain chemistry and energy to the band, and it takes the four of us to recreate that." Running the gamut from 1970's era classic rock (Led Zeppelin's "Immigrant Song," Deep Purple's "Highway Star," Kiss' "Shout It Out Loud," etc.) to 1980's era heavy metal (Black Sabbath's "Heaven and Hell," the Scorpions' "Blackout," "Iron Maiden's "The Trooper," etc.), 'The Covering' is certain to be a most welcomed addition to Stryper fan's album collections. -

Heavy Metal Under Scrutiny: the Controversial Battle for the Protection of America’S Youth

Heavy Metal under Scrutiny: The Controversial Battle for the Protection of America’s Youth Master’s Thesis in North American Studies Leiden University Chrysanthi Papazoglou s1588419 Supervisor: Dr. Eduard van de Bilt 1 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................... 2 Heavy Metal: Origins, Imagery and Values ......................................................... 6 The 1985 PMRC Senate Hearing & Aftermath .................................................. 20 Heavy Metal on Trial: The Cases of Ozzy Osbourne and Judas Priest .............. 41 Conclusion .......................................................................................................... 53 Bibliography ....................................................................................................... 57 2 Introduction During the 1980s, following the steady rise of neo-conservatism, several political and religious groups were formed to fight for what they deemed the loss of true American values. Among their targets was a music genre called heavy metal. Ever since its emergence, the genre met with serious opposition. Accused of promoting violence, suicide, drug and alcohol abuse and distorted images of sex, heavy metal music was considered a threat to the well-being of America’s youth. These accusations were major arguments in the 1980s religious conservatives’ crusade to establish family values. Trying to raise parents’ awareness of the music’s ostensible catastrophic effects on adolescents, -

S = Signing, P = Performance/Product Demonstration, PC = Press Conference

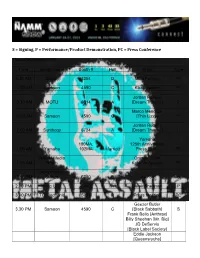

S = Signing, P = Performance/Product Demonstration, PC = Press Conference Thursday January 24th Time Booth Name Booth # Hall Artist Type 9.30 AM Sabian 3254 D Mike Portnoy PC 10.00 AM Samson 4590 C Kiko Loureiro P Jordan Rudess 10.30 AM MOTU 6514 A [Dream Theater] P Marco Mendoza 10.30 AM Samson 4590 C [Thin Lizzy] P Jordan Rudess 11.00 AM Synthogy 6724 A [Dream Theater] P Yamaha 100MA, 125th Anniversary 11.00 AM Yamaha 102MA Marriott Press Event PC NAMM Media Orange Amps 11.00 AM Room Keynote Speech PC Dean Markley 12.00 PM Strings 5710 B Lita Ford S 2.30 PM Korg USA 6440 A Derek Sherinian P 3.00 PM TC Electronic 5932 B Press Meeting PC Geezer Butler 3.30 PM Samson 4590 C [Black Sabbath] S Frank Bello [Anthrax] Billy Sheehan [Mr. Big] JD DeServio [Black Label Society] Eddie Jackson [Queensryche] Marco Mendoza [Thin Lizzy] Steve Morse 4.00 PM TC Electronic 5932 B [Deep Purple] S Guthrie Govan [The Aristocrats] 4.30 PM Samson 4590 C Richie Kotzen P Friday January 25th Time Booth Name Booth Number Hall Artist Type 100 MA, 102 9.30 AM Yamaha MA Marriott Tommy Aldridge PC Matt Halpern [Periphery] Jordan Rudess 10.30 AM MOTU 6514 A [Dream Theater] P Zakk Wylde 11.00 AM EMG Pickups 4782 C [Black Label Society] S/PC Richie Faulkner [Judas Priest] Andy James [Sacred Mother Tongue] 11.00 AM Samson 4590 C Richie Kotzen P Jeff Kendrick 11.30 AM Korg USA 6440 A [DevilDriver] P Mike Spreitzer [DevilDriver] Rex Brown 12.00 PM Ampeg 209 A/B Level 2 [Pantera, Kill Devil Hill] S Mike Inez [Alice In Chains] Juan Alderete Dean Markley 12.00 PM Strings 5710 B Orianthi [Alice Cooper] S 12.00 PM Korg USA 6440 A Gus G [Ozzy, Firewind] S Jeff Kendrick [DevilDriver] Mike Spreitzer [DevilDriver] 12.00 PM Samson 4590 C Gary Holt [Exodus] S Mike Portnoy Scott Ian [Anthrax] Charlie Benante [Anthrax] Frank Bello [Anthrax] Dave Lombardo [Slayer, Philm] Kerry King [Slayer] David Ellefson [Megadeth] Billy Sheehan [Mr. -

Bronze, Silver & Gold Medal and Title Winners in 2014

Bronze, Silver & Gold Medal and Title Winners in 2014 Dancing in the River City, Sacramento, CA, California State Championships (January 19 th ): Men’s International Standard 1. Photis Pishiaras & Ronald Jenkins, California, USA Men’s International Latin 1. Photis Pishiaras & Ronald Jenkins, California, USA 2. Kurt Popp & Aaron Palmer, California, USA Men’s International 10-Dance 1. Kurt Popp & Aaron Palmer, California, USA Women's International Standard 1. Sunny Williams & Lauren Allen, California, USA 2. Emily Coles & Kieren Jameson, California, USA Women's International Latin 1. Sunny Williams & Heather Brockett, California, USA 2. Emily Coles & Katerina Blinova, California, USA Women’s American 9-Dance 1. Genevieve Faria & Jamie Cooper, Massachusetts, USA Showdance 1. Genevieve Faria & Jamie Cooper, Massachusetts, USA Formation Team 1. Trip The Light Fantastic, California, USA 2. Qformation, California, USA Philadelphia Liberty Dance Challenge, Philadelphia, PA, Pennsylvania State Championships (March 29 th ): Men’s International Standard 1. Chris Nunez & Bill Grainer, Pennsylvania/Ohio, USA Men’s International Latin 1. Nik Pavlov & Tomas Delgado, Pennsylvania, USA Men’s American Smooth 1. Jonathan Carbrera & Gene LaPierre, New Jersey, USA 2. Zachary Bordonaro & Michael Sweet, Massachusetts, USA 3. Anthony Mauriello & Tomas Delgado, Pennsylvania, USA Men’s American Rhythm 1. Jonathan Carbrera & Anton Shcliver, New Jersey, USA Showdance 1. Mary Ellen Meyerdierks & Lisa Pateinoster, New Jersey, USA Formation Team 1. LaPierre Ballroom Dance Studio Team, New Jersey, USA April Follies, Oakland, CA, US Championships (April 26 th ): Men’s International Standard 1. Chris Nunes & Bill Graner, Pennsylvania/Ohio, USA 2. Photis Pishiaras & Ronald Jenkins, California, USA 3. Garret Gerritsen & Rafael Dominguez, California, USA Men’s International Latin 1. -

ASCAP Songwriters and Publishers

Chief,'Litigation'III'Section' Antitrust'Division' U.S.'Department'of'Justice' 450'5th'Street'NW,'Suite'4000' Washington,'DC'20001' ' Re:'Justice'Department'Review'of'the'ASCAP'and'BMI'Consent'Decrees' ' To'the'Chief'of'the'Litigation'III'Section:' ' Each'of'us'is'a'songwriter'and'a'member'of'ASCAP,'an'association'that'we'are'proud'to'be'a'part'of'and'that'we' greatly'value.' ' We'write'today'in'response'to'the'Justice'Department’s'request'for'public'comments'on'the'issue'of'whether' ASCAP'and'BMI’s'consent'decrees'should'require'the'PROs'to'license'on'a'100%'basis,'as'opposed'to'fractionally' licensing'jointlyTowned'songs,'which'has'been'the'historical'industry'practice.'It’s'critical'that'our'voices'are' heard,'because'a'shift'to'100%'licensing'would'negatively'impact'our'creative'freedom,'our'ability'to'choose' which'PRO'licenses'our'music'and,'ultimately,'our'livelihood'as'songwriters.' ' Songwriters'are'the'ultimate'small'business'owners.'Many'of'us'have'families'that'depend'on'the'income'we' receive'from'ASCAP.'We'have'carefully'chosen'ASCAP'as'our'PRO'for'multiple'reasons:'the'trusted'relationships' we’ve'developed'there;'the'opportunities'ASCAP'provides'for'our'music'to'be'heard;'the'various'training'and' networking'opportunities'ASCAP'provides;'and'ultimately,'the'way'ASCAP'values'our'music'and'fights'for' writers'to'get'fees'that'reflect'the'fair'value'of'our'work.' ' Like'most'modern'songwriters,'we'often'choose'to'collaborate'with'other'writers.'Just'recently,'every'song'in' the'Top'10'on'Billboard’s'Pop,'Country,'Christian,'and'R&B/HipTHop'charts'was'the'result'of'collaboration.'If'the'