Arxiv:2002.02611V3 [Cond-Mat.Str-El] 24 Nov 2020 and Thus the VP Is Switched, As Shown in Fig.1(C)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tianjin Travel Guide

Tianjin Travel Guide Travel in Tianjin Tianjin (tiān jīn 天津), referred to as "Jin (jīn 津)" for short, is one of the four municipalities directly under the Central Government of China. It is 130 kilometers southeast of Beijing (běi jīng 北京), serving as Beijing's gateway to the Bohai Sea (bó hǎi 渤海). It covers an area of 11,300 square kilometers and there are 13 districts and five counties under its jurisdiction. The total population is 9.52 million. People from urban Tianjin speak Tianjin dialect, which comes under the mandarin subdivision of spoken Chinese. Not only is Tianjin an international harbor and economic center in the north of China, but it is also well-known for its profound historical and cultural heritage. History People started to settle in Tianjin in the Song Dynasty (sòng dài 宋代). By the 15th century it had become a garrison town enclosed by walls. It became a city centered on trade with docks and land transportation and important coastal defenses during the Ming (míng dài 明代) and Qing (qīng dài 清代) dynasties. After the end of the Second Opium War in 1860, Tianjin became a trading port and nine countries, one after the other, established concessions in the city. Historical changes in past 600 years have made Tianjin an unique city with a mixture of ancient and modem in both Chinese and Western styles. After China implemented its reforms and open policies, Tianjin became one of the first coastal cities to open to the outside world. Since then it has developed rapidly and become a bright pearl by the Bohai Sea. -

Ideophones in Middle Chinese

KU LEUVEN FACULTY OF ARTS BLIJDE INKOMSTSTRAAT 21 BOX 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË ! Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas'Van'Hoey' ' Presented(in(fulfilment(of(the(requirements(for(the(degree(of(( Master(of(Arts(in(Linguistics( ( Supervisor:(prof.(dr.(Jean=Christophe(Verstraete((promotor)( ( ( Academic(year(2014=2015 149(431(characters Abstract (English) Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas Van Hoey This M.A. thesis investigates ideophones in Tang dynasty (618-907 AD) Middle Chinese (Sinitic, Sino- Tibetan) from a typological perspective. Ideophones are defined as a set of words that are phonologically and morphologically marked and depict some form of sensory image (Dingemanse 2011b). Middle Chinese has a large body of ideophones, whose domains range from the depiction of sound, movement, visual and other external senses to the depiction of internal senses (cf. Dingemanse 2012a). There is some work on modern variants of Sinitic languages (cf. Mok 2001; Bodomo 2006; de Sousa 2008; de Sousa 2011; Meng 2012; Wu 2014), but so far, there is no encompassing study of ideophones of a stage in the historical development of Sinitic languages. The purpose of this study is to develop a descriptive model for ideophones in Middle Chinese, which is compatible with what we know about them cross-linguistically. The main research question of this study is “what are the phonological, morphological, semantic and syntactic features of ideophones in Middle Chinese?” This question is studied in terms of three parameters, viz. the parameters of form, of meaning and of use. -

Optimization of Three-Echelon Inventory Project for Equipment Spare Parts Based on System Support Degree

IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science PAPER • OPEN ACCESS Optimization of three-echelon inventory project for equipment spare parts based on system support degree To cite this article: Song-shi Shao and Min-zhi Ruan 2017 IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 81 012107 View the article online for updates and enhancements. This content was downloaded from IP address 170.106.34.90 on 25/09/2021 at 14:25 MSETEE 2017 IOP Publishing IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science1234567890 81 (2017) 012107 doi :10.1088/1755-1315/81/1/012107 Optimization of three-echelon inventory project for equipment spare parts based on system support degree SHAO Song-shi, RUAN Min-zhi College of Science, Naval University of Engineering, Wuhan 430033, China Abstract: Management of three-echelon maintenance and supply is a common support mode, in which the spare parts inventory project is one of the critical factors for system availability. Focus on the actual problem of the equipment support engineering, the system spare parts are divided into two levels, and based on the METRIC theory, the three-echelon support evaluation model for system spare parts is established. The three-echelon system support degree is used as the optimization target while the cost is taken as the restriction, and the margin analysis method is applied to inventory project optimization. In a given example, the optimal inventory project and the distribution rule for spare parts is got, and the influencing factors for spare parts inventory is analyzed. The optimization result is consistent with the basic principle under the three-echelon support pattern, which can supply decision assistance for equipment support personal to design a reasonable project. -

Newcastle 1St April

Postpositions vs. prepositions in Mandarin Chinese: The articulation of disharmony* Redouane Djamouri Waltraud Paul John Whitman [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Centre de recherches linguistiques sur l‟Asie orientale (CRLAO) Department of Linguistics EHESS - CNRS, Paris Cornell University, Ithaca, NY NINJAL, Tokyo 1. Introduction Whitman (2008) divides word order generalizations modelled on Greenberg (1963) into three types: hierarchical, derivational, and crosscategorial. The first reflect basic patterns of selection and encompass generalizations like those proposed in Cinque (1999). The second reflect constraints on synactic derivations. The third type, crosscategorial generalizations, assert the existence of non-hierarchical, non-derivational generalizations across categories (e.g. the co-patterning of V~XP with P~NP and C~TP). In common with much recent work (e.g. Kayne 1994, Newmeyer 2005), Whitman rejects generalizations of the latter type - that is, generalizations such as the Head Parameter – as components of Universal Grammar. He argues that alleged universals of this type are unfailingly statistical (cf. Dryer 1998), and thus should be explained as the result of diachronic processes, such as V > P and V > C reanalysis, rather than synchronic grammar. This view predicts, contra the Head Parameter, that „mixed‟ or „disharmonic‟ crosscategorial word order properties are permitted by UG. Sinitic languages contain well- known examples of both types. Mixed orders are exemplified by prepositions, postpositions and circumpositions occurring in the same language. Disharmonic orders found in Chinese languages include head initial VP-internal order coincident with head final NP-internal order and clause-final complementizers. Such combinations are present in Chinese languages since their earliest attestation. -

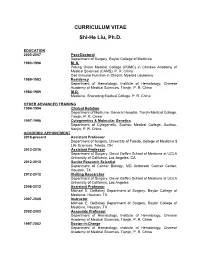

CURRICULUM VITAE Shi-He Liu, Ph.D

CURRICULUM VITAE Shi-He Liu, Ph.D. EDUCATION 2003-2007 Post-Doctoral Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine 1993-1996 M. S. Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) in Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS). P. R. China Cell Immune Function in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia 1989-1993 Residency Department of Hematology, Institute of Hematology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Tianjin, P. R. China 1984-1989 M.D. Medicine, Shandong Medical College, P. R. China OTHER ADVANCED TRAINING 1994-1994 Clinical Rotation Department of Medicine, General Hospital, Tianjin Medical College, Tianjin, P. R. China 1997-1998 Cytogenetics & Molecular Genetics Department of Cytogenetic, Suzhou Medical College, Suzhou, Nanjin, P. R. China ACADEMIC APPOINTMENT 2016-present Assistant Professor Department of Surgery, University of Toledo, College of Medicine $ Life Sciences, Toledo, OH 2013-2016 Assistant Professor Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA University of California, Los Angeles, CA 2012-2013 Senior Research Scientist Department of Cancer Biology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 2012-2012 Visiting Researcher Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA University of California, Los Angeles 2008-2012 Assistant Professor Michael E. DeBakey Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 2007-2008 Instructor Michael E. DeBakey Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 2002-2003 Associate Professor Department of Hematology, Institute of Hematology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Tianjin, P. R. China 1997-2002 Doctor-in-Charge Department of Hematology, Institute of Hematology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Tianjin, P. R. China HONORS OR AWARDS 2015 Hirshberg Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research award. -

Names of Chinese People in Singapore

101 Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 7.1 (2011): 101-133 DOI: 10.2478/v10016-011-0005-6 Lee Cher Leng Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore ETHNOGRAPHY OF SINGAPORE CHINESE NAMES: RACE, RELIGION, AND REPRESENTATION Abstract Singapore Chinese is part of the Chinese Diaspora.This research shows how Singapore Chinese names reflect the Chinese naming tradition of surnames and generation names, as well as Straits Chinese influence. The names also reflect the beliefs and religion of Singapore Chinese. More significantly, a change of identity and representation is reflected in the names of earlier settlers and Singapore Chinese today. This paper aims to show the general naming traditions of Chinese in Singapore as well as a change in ideology and trends due to globalization. Keywords Singapore, Chinese, names, identity, beliefs, globalization. 1. Introduction When parents choose a name for a child, the name necessarily reflects their thoughts and aspirations with regards to the child. These thoughts and aspirations are shaped by the historical, social, cultural or spiritual setting of the time and place they are living in whether or not they are aware of them. Thus, the study of names is an important window through which one could view how these parents prefer their children to be perceived by society at large, according to the identities, roles, values, hierarchies or expectations constructed within a social space. Goodenough explains this culturally driven context of names and naming practices: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore The Shaw Foundation Building, Block AS7, Level 5 5 Arts Link, Singapore 117570 e-mail: [email protected] 102 Lee Cher Leng Ethnography of Singapore Chinese Names: Race, Religion, and Representation Different naming and address customs necessarily select different things about the self for communication and consequent emphasis. -

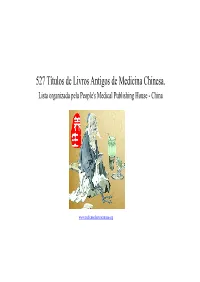

527 Títulos De Livros Antigos De Medicina Chinesa. Lista Organizada Pela People's Medical Publishing House - China

527 Títulos de Livros Antigos de Medicina Chinesa. Lista organizada pela People's Medical Publishing House - China www.medicinaclassicachinesa.org Vários desses livros podem ser encontrados em versão gratuita no site http://www.zysj.com.cn/lilunshuji/5index.html 中文名 作者名(字号) 出书年代 Titulo em 拼音 英文名 Nome Real ou Literário Data em que escrito Chinês Pin Yin Titulo em Inglês do Autor ou publicado. Zhang Zhong‐hua 张仲 华 (Style 号 Zhang Ai‐lu 1. 爱庐医案 Ài Lú Yī Àn [Zhang] Ai‐lu’s Case Records 张爱庐) 2. 敖氏伤寒金镜 Ao’s Golden Mirror Records for Cold 录 Áo Shì Shāng Hán Jīn Jìng Lù Damage Du Qing‐bi 杜清碧 1341 3. 百草镜 Băi Căo Jìng Mirror of the Hundred Herbs Zhao Xue‐kai 赵学楷 Qing 4. 白喉条辨 Bái Hóu Tiáo Biàn Systematic Analysis of Diphtheria Chen Bao‐shan 陈宝善 1887 5. 百一选方 Băi Yī Xuăn Fāng Selected Formulas Wang Qiu 王璆 1196 Wan Quan 万全 (Style: 6. 保命歌诀 Băo Mìng Gē Jué Verses for Survival Wan Mi 万密) 7. 保婴撮要 Băo Yīng Cuō Yào Essentials of Infant Care Xue Kai 薛凯 1555 Ge Hong 葛洪 (Styles: Ge Zhi‐chuan 葛稚川, 8. 抱朴子内外篇 Bào Pŭ Zĭ Nèi Wài Piān The Inner and Outer Chapters of Bao Pu‐zi Bao Pu‐zi 抱朴子) Wen Ren Qi Nian 闻人耆 9. 备急灸法 Bèi Jí Jiŭ Fă Moxibustion Techniques for Emergency 年 1226 Important Formulas Worth a Thousand 7th century; 652 10. 备急千金要方 Bèi Jí Qiān Jīn Yào Fāng Gold Pieces for Emergency Sun Si‐miao 孙思邈 (Tang) Wang Ang 汪昂 (Style: 11. 本草备要 Bĕn Căo Bèi Yào Essentials of Materia Medica Wang Ren‐an) 1664 (Qing) Zhang Bing‐cheng 张秉 12. -

Zhenzhong Zeng School of Environmental Science And

Zhenzhong Zeng School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Southern University of Science and Technology [email protected] | https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=GsM4YKQAAAAJ&hl=en CURRENT POSITION Associate Professor, Southern University of Science and Technology, since 2019.09.04 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Postdoctoral Research Associate, Princeton University, 2016-2019 (Mentor: Dr. Eric F. Wood) EDUCATION Ph.D. in Physical Geography, Peking University, 2011-2016 (Supervisor: Dr. Shilong Piao) B.S. in Geography Science, Sun Yat-Sen University, 2007-2011 RESEARCH INTERESTS Global change and the earth system Biosphere-atmosphere interactions Terrestrial hydrology Water and agriculture resources Climate change and its impacts, with a focus on China and the tropics AWARDS & HONORS 2019 Shenzhen High Level Professionals – National Leading Talents 2018 “China Agricultural Science Major Progress” - Impacts of climate warming on global crop yields and feedbacks of vegetation growth change on global climate, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences 2016 Outstanding Graduate of Peking University 2013 – 2016 Presidential (Peking University) Scholarship; 2014 – 2015 Peking University PhD Projects Award; 2013 – 2014 Peking University "Innovation Award"; 2013 – 2014 National Scholarship; 2012 – 2013 Guanghua Scholarship; 2011 – 2012 National Scholarship; 2011 – 2012 Founder Scholarship 2011 Outstanding Graduate of Sun Yat-Sen University 2009 National Undergraduate Mathematical Contest in Modeling (Provincial Award); 2009 – 2010 National Scholarship; 2008 – 2009 National Scholarship; 2007 – 2008 Guanghua Scholarship PUBLICATION LIST 1. Liu, X., Huang, Y., Xu, X., Li, X., Li, X.*, Ciais, P., Lin, P., Gong, K., Ziegler, A. D., Chen, A., Gong, P., Chen, J., Hu, G., Chen, Y., Wang, S., Wu, Q., Huang, K., Estes, L. & Zeng, Z.* High spatiotemporal resolution mapping of global urban change from 1985 to 2015. -

Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 2003 Number 129 Article 6 2-1-2003 Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans Sheau-yueh J. Chao Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Chao, Sheau-yueh J. (2003) "Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 2003 : No. 129 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol2003/iss129/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. researching YOUR ASIAN ROOTS CHINESE AMERICANS sheau yueh J chao baruch college city university new york introduction situated busiest mid town manhattan baruch senior colleges within city university new york consists twenty campuses spread five boroughs new york city intensive business curriculum attracts students country especially those asian pacific ethnic background encompasses nearly 45 entire student population baruch librarian baruch college city university new york I1 encountered various types questions serving reference desk generally these questions solved without major difficulties however beginning seven years ago unique question referred me repeatedly each new semester began how I1 find reference book trace my chinese name resource english help me find origin my chinese surname -

Recent Advances in Annonaceous Acetogenins By

Recent Advances in Annonaceous Acetogenins By: Lu Zeng, Qing Ye, Nicholas H. Oberlies, Guoen Shi, Zhe-Ming Gu, Kan He and Jerry L. McLaughlin Zeng, L.; Ye, Q.; Oberlies, N.H.; Shi, G.; Gu, Z.-M.; He, K. and McLaughlin, J.L. (1996) Recent advances in Annonaceous acetogenins. Natural Product Reports, 13, 275-306. Made available courtesy of Royal Society of Chemistry: http://www.rsc.org/Publishing/Journals/np/ ***Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document 1 Introduction Annonaceous acetogenins are waxy substances consisting of C32 or C34 long chain fatty acids which have been combined with a propan-2-ol unit at C-2 to form a gama-lactone. They are only found in several genera of the plant family, Annonaceae. Their diverse bioactivities as antitumour, immunosuppressive, pesticidal, antiprotozoal, antifeedant, anthelmintic and antimicrobial agents have attracted more and more interest worldwide. Recently, we reported that the Annonaceous acetogenins can selectively inhibit the growth of cancerous cells and also inhibit the growth of adriamycin resistant tumour cells.1 As more acetogenins have been isolated and additional cytotoxicity assays have been conducted, we have noticed that, al(hough most acetogenins have high potencies among several solid human tumour cells lines, some of the derivatives within the different structural types and some positional isomers show remarkable selectivities among certain cell lines, e.g. against prostate cancer (PC-3).2 We now understand the primary modes of action for the acetogenins. They -

A Comparison of the Korean and Japanese Approaches to Foreign Family Names

15 A Comparison of the Korean and Japanese Approaches to Foreign Family Names JIN Guanglin* Abstract There are many foreign family names in Korean and Japanese genealogies. This paper is especially focused on the fact that out of approximately 280 Korean family names, roughly half are of foreign origin, and that out of those foreign family names, the majority trace their beginnings to China. In Japan, the Newly Edited Register of Family Names (新撰姓氏錄), published in 815, records that out of 1,182 aristocratic clans in the capital and its surroundings, 326 clans—approximately one-third—originated from China and Korea. Does the prevalence of foreign family names reflect migration from China to Korea, and from China and Korea to Japan? Or is it perhaps a result of Korean Sinophilia (慕華思想) and Japanese admiration for Korean and Chinese cultures? Or could there be an entirely distinct explanation? First I discuss premodern Korean and ancient Japanese foreign family names, and then I examine the formation and characteristics of these family names. Next I analyze how migration from China to Korea, as well as from China and Korea to Japan, occurred in their historical contexts. Through these studies, I derive answers to the above-mentioned questions. Key words: family names (surnames), Chinese-style family names, cultural diffusion and adoption, migration, Sinophilia in traditional Korea and Japan 1 Foreign Family Names in Premodern Korea The precise number of Korean family names varies by record. The Geography Annals of King Sejong (世宗實錄地理志, 1454), the first systematic register of Korean family names, records 265 family names, but the Survey of the Geography of Korea (東國輿地勝覽, 1486) records 277. -

A Study of Xu Xu's Ghost Love and Its Three Film Adaptations THESIS

Allegories and Appropriations of the ―Ghost‖: A Study of Xu Xu‘s Ghost Love and Its Three Film Adaptations THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Qin Chen Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Master's Examination Committee: Kirk Denton, Advisor Patricia Sieber Copyright by Qin Chen 2010 Abstract This thesis is a comparative study of Xu Xu‘s (1908-1980) novella Ghost Love (1937) and three film adaptations made in 1941, 1956 and 1995. As one of the most popular writers during the Republican period, Xu Xu is famous for fiction characterized by a cosmopolitan atmosphere, exoticism, and recounting fantastic encounters. Ghost Love, his first well-known work, presents the traditional narrative of ―a man encountering a female ghost,‖ but also embodies serious psychological, philosophical, and even political meanings. The approach applied to this thesis is semiotic and focuses on how each text reflects the particular reality and ethos of its time. In other words, in analyzing how Xu‘s original text and the three film adaptations present the same ―ghost story,‖ as well as different allegories hidden behind their appropriations of the image of the ―ghost,‖ the thesis seeks to broaden our understanding of the history, society, and culture of some eventful periods in twentieth-century China—prewar Shanghai (Chapter 1), wartime Shanghai (Chapter 2), post-war Hong Kong (Chapter 3) and post-Mao mainland (Chapter 4). ii Dedication To my parents and my husband, Zhang Boying iii Acknowledgments This thesis owes a good deal to the DEALL teachers and mentors who have taught and helped me during the past two years at The Ohio State University, particularly my advisor, Dr.