The Fall and Rise of Blasphemy Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 40 2.Indb

FREEDOM BEYOND THE COMMONS: MANAGING THE TENSION BETWEEN FAITH AND EQUALITY IN A MULTICULTURAL SOCIETY JOEL HARRISON* AND PATRICK PARKINSON** As religious traditions and equality norms increasingly collide, commentators in Australia have questioned the existence and scope of exceptions to anti-discrimination law for religious bodies. The authors argue that this presents a shifting understanding of anti-discrimination law’s purpose. Rather than focusing on access or distribution, anti- discrimination law is said to centre on self-identity. When justifi ed by this and related values, anti-discrimination law tends towards a universal application — all groups must cohere to its norms. In defending religion- based exceptions, the authors argue that this universalising fails to recognise central principles of religious liberty (principally the authority of the group) and the multicultural reality of Australia. The authors argue that more attention should be given to a social pluralist account of public life and the idea of a federation of cultures. Non-discrimination norms ought to operate in the ‘commons’ in which members of the community come together in a shared existence, and where access and participation rights need to be protected. Beyond the commons, however, different groups should be able to maintain their identity and different beliefs on issues such as sexual practice through, where relevant, their staffi ng, membership or service provision policies. I INTRODUCTION In recent years, there has been growing tension in Australia and elsewhere between churches, other faith groups, and equality advocates concerning the reach of anti-discrimination laws. This refl ects a broader tension that has arisen between religion and the human rights movement,1 despite a long history of involvement by people of faith in leadership on human rights issues.2 There are * BA/LLB (Hons) (Auck); MSt, DPhil (Oxon). -

BLASPHEMY LAWS in the 21ST CENTURY: a VIOLATION of HUMAN RIGHTS in PAKISTAN Fanny Mazna Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School 2017 BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN Fanny Mazna Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Mazna, Fanny. "BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN." (Jan 2017). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN by Fanny Mazna B.A., Kinnaird College for Women, 2014 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Department of Mass Communication and Media Arts in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2017 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN By Fanny Mazna A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the field of Mass Communication and Media Arts Approved by: William Babcock, Co-Chair William Freivogel, Co-Chair Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April, 6th 2017 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF FANNY MAZNA, for the Master of Science degree in MASS COMMUNICATION AND MEDIA ARTS presented on APRIL, 6th 2017, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY- A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. -

Statement by Dr. Richard Benkin

Dr. Richard L. Benkin ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Email: [email protected] http://www.InterfaithStrength.com Also Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn Bangladesh: “A rose by any other name is still blasphemy.” Written statement to US Commission on Religious Freedom Virtual Hearing on Blasphemy Laws and the Violation of International Religious Freedom Wednesday, December 9, 2020 Dr. Richard L. Benkin Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” While few people champion an unrestricted right to free of expression, fewer still stand behind the use of state power to protect a citizen’s right from being offended by another’s words. In the United States, for instance, a country regarded by many correctly or not as a “Christian” nation, people freely produce products insulting to many Christians, all protected, not criminalized by the government. A notorious example was a painting of the Virgin Mary with elephant dung in a 1999 Brooklyn Museum exhibit. Attempts to ban it or sanction the museum failed, and a man who later defaced the work to redress what he considered an anti-Christian slur was convicted of criminal mischief for it. Laws that criminalize free expression as blasphemy are incompatible with free societies, and nations that only pose as such often continue persecution for blasphemy in disguise. In Bangladesh, the government hides behind high sounding words in a toothless constitution while sanctioning blasphemy in other guises. -

How Should Muslims Think About Apostasy Today?

2 | The Issue of Apostasy in Islam Author Biography Dr. Jonathan Brown is Director of Research at Yaqeen Institute, and an Associate Professor and Chair of Islamic Civilization at Georgetown University. Disclaimer: The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in these papers and articles are strictly those of the authors. Furthermore, Yaqeen does not endorse any of the personal views of the authors on any platform. Our team is diverse on all fronts, allowing for constant, enriching dialogue that helps us produce high-quality research. Copyright © 2017. Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research 3 | The Issue of Apostasy in Islam The Shari’ah consists of some laws that remain the same regardless of changing circumstances and others that change with them. Most of the Shari’ah is up to individual Muslims to follow in their own lives. Some are for judges to implement in courts. Finally, the third set of laws is for the ruler or political authority to implement based on the best interests of society. The Shari’ah ruling on Muslims who decide to leave Islam belongs to this third group. Implemented in the past to protect the integrity of the Muslim community, today this important goal can best be reached by Muslim governments using their right to set punishments for apostasy aside. One of the most common accusations leveled against Islam involves the freedom of religion. The problem, according to critics: Islam doesn’t have any. This criticism might strike some as odd since it has been well established that both the religion of Islam and Islamic civilization have shown a level of religious tolerance that would make modern Americans blush. -

New Religious Movements

New Religious Movements New Religious Movements: Challenge and response is a searching and wide-ranging collection of essays on the contemporary phenomenon of new religions. The contributors to this volume are all established specialists in the sociology, theology, law, or the history of new minority movements. The primary focus is the response of the basic institutions of society to the challenge which new religious movements represent. The orientation of this volume is to examine the way in which new movements in general have affected modern society in areas such as economic organisation; the operation of the law; the role of the media; the relationship of so-called ‘cult’ membership to mental health; and the part which women have played in leading or supporting new movements. Specific instances of these relationships are illustrated by reference to many of the most prominent new religions – Hare Krishna, The Brahma Kumaris, The Unification Church, The Jesus Army, The Family’, The Church of Scientology, and Wicca. For students of religion or sociology, New Religious Movements is an invaluable source of information, an example of penetrating analysis, and a series of thought-provoking contributions to a debate which affects many areas of contemporary life in many parts of the world. Contributors: Eileen Barker, James Beckford, Anthony Bradney, Colin Campbell, George Chryssides, Peter Clarke, Paul Heelas, Massimo Introvigne, Lawrence Lilliston, Gordon Melton, Elizabeth Puttick, Gary Shepherd, Colin Slee, Frank Usarski, Bryan Wilson. Bryan Wilson is an Emeritus Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford. He is the author and editor of several books on sects and New Religious Movements. -

Apostasy and the Notion of Religious Freedom in Islam Sherazad Hamit Macalester College

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@Macalester College Macalester Islam Journal Volume 1 Spring 2006 Article 4 Issue 2 10-11-2006 Apostasy and the Notion of Religious Freedom in Islam Sherazad Hamit Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/islam Recommended Citation Hamit, Sherazad (2006) "Apostasy and the Notion of Religious Freedom in Islam," Macalester Islam Journal: Vol. 1: Iss. 2, Article 4. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/islam/vol1/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religious Studies Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Macalester Islam Journal by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hamit: Apostasy and the Notion of Religious Freedom in Islam Macalester Islam Journal Fall 2006 page 31 ______________________________________________________ Apostasy and the Notion of Religious Freedom in Islam Sherazad Hamit ‘07 This paper will argue that the Afghan Government’s sentencing to death of native Abdul Rahman as an apostate goes against Qur’anic decrees on apostasy and is therefore un-Islamic, given the context of the apostate in question. Published by DigitalCommons@Macalester College, 2006 1 Macalester Islam Journal, Vol. 1 [2006], Iss. 2, Art. 4 Macalester Islam Journal Fall 2006 page 32 ______________________________________________________ Apostasy and the Notion of Religious Freedom in Islam Sherazad Hamit ‘07 The question of whether or not Islam allows for freedom of worship has once again resurfaced as a topic of contention, this time in relation to the Afghan government sentencing of native Abdul Rahman to death as an apostate because of his conversion to Christianity sixteen years ago. -

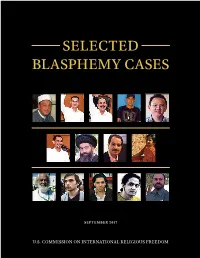

Selected Blasphemy Cases

SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES SEPTEMBER 2017 U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Mohamed Basuki “Ahok” Abdullah al-Nasr Andry Cahya Ahmed Musadeq Sebastian Joe Tjahaja Purnama EGYPT INDONESIA INDONESIA INDONESIA INDONESIA Ayatollah Mohammad Mahful Muis Kazemeini Mohammad Tumanurung Boroujerdi Ali Taheri Aasia Bibi INDONESIA IRAN IRAN PAKISTAN Ruslan Sokolovsky Abdul Shakoor RUSSIAN Raif Badawi Ashraf Fayadh Shankar Ponnam PAKISTAN FEDERATION SAUDI ARABIA SAUDI ARABIA SAUDI ARABIA UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES SEPTEMBER 2017 WWW.USCIRF.GOV COMMISSIONERS Daniel Mark, Chairman Sandra Jolley, Vice Chair Kristina Arriaga de Bucholz, Vice Chair Tenzin Dorjee Clifford D. May Thomas J. Reese, S.J. John Ruskay Jackie Wolcott Erin D. Singshinsuk Executive Director PROFESSIONAL STAFF Dwight Bashir, Director of Research and Policy Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Director of International Law and Policy Judith E. Golub, Director of Congressional Affairs & Policy and Planning John D. Lawrence, Director of Communications Elise Goss-Alexander, Researcher Andrew Kornbluth, Policy Analyst Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Tina L. Mufford, Senior Policy Analyst Jomana Qaddour, Policy Analyst Karen Banno, Office Manager Roy Haskins, Manager of Finance and Administration Travis Horne, Communications Specialist SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES Many countries today have blasphemy laws. Blasphemy is defined as “the act of insulting or showing contempt or lack of reverence for God.” Across the globe, billions of people view blasphemy as deeply offensive to their beliefs. Respecting Rights? Measuring the World’s • Violate international human rights standards; Blasphemy Laws, a U.S. Commission on Inter- • Often are vaguely worded, and few specify national Religious Freedom (USCIRF) report, or limit the forum in which blasphemy can documents the 71 countries – ranging from occur for purposes of punishment; Canada to Pakistan – that have blasphemy • Are inconsistent with the approach laws (as of June 2016). -

Human Rights: Religious Freedom, (2021)

Human rights: religious freedom, (2021) Human rights: religious freedom Last date of review: 02 March 2021 Last update: General updating Authored by Austen Morgan 33 Bedford Row Chambers Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights, guaranteeing “freedom of thought, conscience and religion” (and now given further effect through Sch.1 of the Human Rights Act 1998), reads: (1) everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public and private, to manifest his religion or belief, in worship, teaching, practice and observance. (2) freedom to manifest one’s religion or beliefs shall be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of public safety, for the protection of public order, health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others. The structure of the article, elaborated upon by s.3(1) of the Human Rights Act 1998, indicates the following: the freedom is very broad, including thought and conscience as well as religion; the second particularisation in art.9(1) relates to the manifestation of “religion or belief”, through essentially worship; the limitation in art.9(2) bites only on the manifestation of religion or belief (as permitted); and the justification permitting interference by public authorities is not as broad as in art.8 (private and family life), art.10 (freedom of expression) and art.11 (freedom of assembly and association). -

Blasphemy Law and Public Neutrality in Indonesia

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 8 No 2 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy March 2017 Research Article © 2017 Victor Imanuel W. Nalle. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Blasphemy Law and Public Neutrality in Indonesia Victor Imanuel W. Nalle Faculty of Law, Darma Cendika Catholic University, Indonesia Doi:10.5901/mjss.2017.v8n2p57 Abstract Indonesia has the potential for social conflict and violence due to blasphemy. Currently, Indonesia has a blasphemy law that has been in effect since 1965. The blasphemy law formed on political factors and tend to ignore the public neutrality. Recently due to a case of blasphemy by the Governor of Jakarta, relevance of blasphemy law be discussed again. This paper analyzes the weakness of the blasphemy laws that regulated in Law No. 1/1965 and interpretation of the Constitutional Court on the Law No. 1/1965. The analysis in this paper, by statute approach, conceptual approach, and case approach, shows the weakness of Law No. 1/1965 in putting itself as an entity that is neutral in matters of religion. This weakness caused Law No. 1/1965 set the Government as the interpreter of the religion scriptures that potentially made the state can not neutral. Therefore, the criminalization of blasphemy should be based on criteria without involving the state as an interpreter of the theological doctrine. Keywords: constitutional right, blasphemy, religious interpretation, criminalization, public neutrality 1. Introduction Indonesia is a country with a high level of trust toward religion. -

The Following Full Text Is a Publisher's Version

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/106793 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-01 and may be subject to change. The Judge, the Occupier, his Laws, and their Validity: Judicial Review by the Supreme Courts of Occupied Belgium, Norway, and the Netherlands 1940-1945 in the Context of their Professional Conduct and the Consequences for their Public Image Derk Venema 1 Introduction Under the German occupation in World War II, the supreme courts of the Netherlands, Belgium, and Norway were forced to form an opinion on the relation between the occupier’s ordinances on the one hand and domestic and international law on the other. The overall attitudes of these three supreme courts towards the occupier are reflected in this one topic: their positions and decisions concerning judicial review of the occupier’s ordinances. For each court, I will give an outline of its behaviour and its own justifications and discuss the consequences of these for their public image. The three case studies will lead to a tentative conclusion about which were the most important factors leading to a positive or a negative image. The International Law of Belligerent Occupation Central to the legal relation between occupier and occupied territory is Article 43 of the Hague Regulations (HR) of 1907. This article still serves as the basis of the international law of occupation, and is clarified, but essentially unaltered by Article 64 of the 4 th Geneva Convention of 1949 2. -

Criminal Law Act 1967 (C

Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. 58) 1 SCHEDULE 4 – Repeals (Obsolete Crimes) Document Generated: 2021-04-04 Status: This version of this schedule contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967, SCHEDULE 4. (See end of Document for details) SCHEDULES SCHEDULE 4 Section 13. REPEALS (OBSOLETE CRIMES) Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 The text of S. 10(2), S. 13(2), Sch. 2 paras. 3, 4, 6, 10, 12(2), 13(1)(a)(c)(d), 14, Sch. 3 and Sch. 4 is in the form in which it was originally enacted: it was not reproduced in Statutes in Force and does not reflect any amendments or repeals which may have been made prior to 1.2.1991. PART I ACTS CREATING OFFENCES TO BE ABOLISHED Chapter Short Title Extent of Repeal 3 Edw. 1. The Statute of Westminster Chapter 25. the First. (Statutes of uncertain date — Statutum de Conspiratoribus. The whole Act. 20 Edw. 1). 28 Edw. 1. c. 11. (Champerty). The whole Chapter. 1 Edw. 3. Stat. 2 c. 14. (Maintenance). The whole Chapter. 1 Ric. 2. c. 4. (Maintenance) The whole Chapter. 16 Ric. 2. c. 5. The Statute of Praemunire The whole Chapter (this repeal extending to Northern Ireland). 24 Hen. 8. c. 12. The Ecclesiastical Appeals Section 2. Act 1532. Section 4, so far as unrepealed. 25 Hen. 8. c. 19. The Submission of the Clergy Section 5. Act 1533. The Appointment of Bishops Section 6. Act 1533. 25 Hen. 8. c. -

Annual Report 2008

Royal Tropical Institute Annual Report 2008 Royal Tropical Institute Health Annual Report Culture 2008 Information & Education Sustainable Economic & Social Development 5 Foreword by the President Content 6 The Institute at a glance 8 1 Health 11 Responding to HIV/AIDS in Namibia 12 Expert meeting on Evaluating Human Resources for Health Interventions 13 Tools for Diagnosis and Resistance monitoring of malaria 17 Controlling Brucellosis in Peru 20 Infectious Diseases network for Treatment and Research in Africa 22 2 Culture 26 Tropenmuseum overview 2008 27 Exhibitions 29 New acquisitions 30 Projects 32 Tropentheater overview 2008 34 Projects 38 3 Information & Education 43 master of Public Health draws students from around the world 44 Search4Dev: providing access to publications of Dutch development organizations 45 Libraries and capacity strengthening in Ghana 49 Building the capacity of HIV and AIDS practitioners through information 50 Diversity within the ministry of Education, Culture and Science 51 Virtual Action Learning, an Innovative Educational Concept 52 KIT to provide Information services for médicins sans Frontières NL 52 Training for Penitentairy Staff 54 4 Sustainable Economic & Social Development 57 Gender and access to justice in Sub-Saharan Africa 58 Sustainable procurement from Developing Countries 61 Tradehouse Yiriwa SA: improving rural livelihoods for small cotton farmers in mali 62 Trading Up: building cooperation between farmers and traders in Africa 63 Innovative Local Governance practices in Guinea 66 Participatory Action Learning an approach for Strengthening Institutional Learning 68 Holding KIT bv 71 KIT Publishers 72 KIT Hotel bv 73 Annona Sustainable Investment Fund 75 mali Biocarburant 76 Reports 78 Financial Report 82 Annual Social Report 84 Corporate Social Responsibility 86 Boards and Council R Guatamalean girls working in the field Photo: Maurits de Koning Q Jan Donner in Mali Photo: Jan Donner Foreword In 2008 the global debate on the ‘new development architecture’ gathered pace.