An Ancient Elixir: Beer in Sumer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ULTIMATE ALMANAG WORLD BEER RECIPES Barrh-Haasgulll

The ULTIMATEALMANAG of WORLDBEER RECIPES A PracticalGuide for the ProfessionalBrewer to the World'sGlassic Beer Styles from Ato Z by HorstDornbusch with Sponsorship& TechnicalEdits by .r(ail- BARrH-HAAsGUlll{w Publishedby CerevisiaCommunications P.O.Box 719 WestNewburV, MA 01985 USA Copyright@ Horst Dornbusch, 2010 All rightsreserved. Without limiting the rightsunder the copyrightreserved above, nopart ofthis publication may be reproduced, stored in or introducedinto a retrievalsystem, or transmitted,in anyform or by anymeans (electronic, mechanical,photocopying, recording, or otherwise),without the priorwritten permissionof the copyrightowner of thisbook, at the addressabove, except by a reviewerwho mayquote brief passages in a review. Printedin Bamberg,Germany SBN:978-0,9844449-0-8 L0987654327 fSB N : 978-0-98 44449 -O-8 ||ilililililil|]ilil|ltililriltiilfl Disclaimer:The recipes in thisbook are based on the author'sand technical editors'combined international brewing experience stretching over several decades.They have also benefitedfrom the technicalexpertise and resourcesavailable within the three sponsorcompanies, the Barth-Haas Group,SCHULZ Brew Systems, and the Weyermann@Malting Company. The recipesare thoroughlyresearched to ensuretheir authenticity.However, becauseclassic beer styles have evolved as part of the livingbrewing past, the authorand technical editors freely and cheerfully admit that theremay be other equallylegitimate interpretations of the brew-historicalrecord. Therefore,style specifications, appropriate ingredients, -

The Epic of Gilgamesh Humbaba from His Days Running Wild in the Forest

Gilgamesh's superiority. They hugged and became best friends. Name Always eager to build a name for himself, Gilgamesh wanted to have an adventure. He wanted to go to the Cedar Forest and slay its guardian demon, Humbaba. Enkidu did not like the idea. He knew The Epic of Gilgamesh Humbaba from his days running wild in the forest. He tried to talk his best friend out of it. But Gilgamesh refused to listen. Reluctantly, By Vickie Chao Enkidu agreed to go with him. A long, long time ago, there After several days of journeying, Gilgamesh and Enkidu at last was a kingdom called Uruk. reached the edge of the Cedar Forest. Their intrusion made Humbaba Its ruler was Gilgamesh. very angry. But thankfully, with the help of the sun god, Shamash, the duo prevailed. They killed Humbaba and cut down the forest. They Gilgamesh, by all accounts, fashioned a raft out of the cedar trees. Together, they set sail along the was not an ordinary person. Euphrates River and made their way back to Uruk. The only shadow He was actually a cast over this victory was Humbaba's curse. Before he was beheaded, superhuman, two-thirds god he shouted, "Of you two, may Enkidu not live the longer, may Enkidu and one-third human. As king, not find any peace in this world!" Gilgamesh was very harsh. His people were scared of him and grew wary over time. They pleaded with the sky god, Anu, for his help. In When Gilgamesh and Enkidu arrived at Uruk, they received a hero's response, Anu asked the goddess Aruru to create a beast-like man welcome. -

Burn Your Way to Success Studies in the Mesopotamian Ritual And

Burn your way to success Studies in the Mesopotamian Ritual and Incantation Series Šurpu by Francis James Michael Simons A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2017 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The ritual and incantation series Šurpu ‘Burning’ is one of the most important sources for understanding religious and magical practice in the ancient Near East. The purpose of the ritual was to rid a sufferer of a divine curse which had been inflicted due to personal misconduct. The series is composed chiefly of the text of the incantations recited during the ceremony. These are supplemented by brief ritual instructions as well as a ritual tablet which details the ceremony in full. This thesis offers a comprehensive and radical reconstruction of the entire text, demonstrating the existence of a large, and previously unsuspected, lacuna in the published version. In addition, a single tablet, tablet IX, from the ten which comprise the series is fully edited, with partitur transliteration, eclectic and normalised text, translation, and a detailed line by line commentary. -

That Just Makes You Tired!

That Just Makes You Tired! Have you ever noticed that mere observation can make you tired? (Well, me neither). However, my son is always the thinker and he made an observation worthy of contemplation, i.e., idolatry is hard work! Yes, says he and here’s why. The Babylonians had at least eleven major gods: Tiamat: in one area she epitomized the beauty of the feminine, while the other showcasing how she represented the chaotic scope of primordial origins,” i.e., in another area she takes “the form of a giant dragon to wreak havoc on the younger generation of gods and is also said to have created the first batch of monsters and ‘poison- filled dragons…” I think I’ve met her. Enlil, Enki, and Anu: It has been reported that Mesopotamian had a supreme triad: Enlil, possibly portrayed as the ‘Lord of Air,’ Anu, god of the heavens, Enki, god of wisdom and earth. Of these it was Enlil “who brought upon the great flood upon humanity because he was “perturbed by their higher rate of fertility and the general ‘noise’ they made (that disturbed his sleep). Enki, translated as the ‘Lord of the Earth,’ has also been depicted as a deity of creation, crafts, intelligence and even magic.” Marduk: Seemingly the most famous of the Babylonian gods. Marduk has been portrayed as ‘the very King of gods (or even Storm God), draped in royal robes, whose fields of ‘expertise’ ranged from justice, healing to agriculture and magic. Historically, the famous ziggurat of Babylon was also dedicated to Marduk, which has been referred to a “the (literary) model for the Biblical Tower of Babel.” Other Babylonian gods included Ishtar, Sin, Shamash, Nisaba, Ashur, and Ninkasi. -

INTRODUCTION to BREWING Marie-Annick Scott

INTRODUCTION TO BREWING Marie-Annick Scott 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS History pg 2 Malt varieties pg 8 Other fermentables pg 9 Hops pg 11 Bittering compounds pg 12 Flavour compounds pg 12 Hop products pg 12 Water pg 14 Yeast pg 18 Equipment pg 20 Mash profiles pg 22 Detailed brew day steps pg 26 After brew day pg 34 Designing your own recipes pg 39 Glossary pg 43 © 2019 Marie-Annick Scott 2 INTRODUCTION TO BREWING Welcome to a one-day course on brewing. During this course you will learn how to transform grains and hops into drinkable beer. Throughout the day, we will be demonstrating how to make beer using your own equipment and guide you through the process to design your very own recipes. Brewing is an extremely old practice, even predating civilisation. Historians like to argue whether beer or bread came first, but we do know that it’s the reason humans started living together, moving from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to farming and eventually, cities. AN EXTREMELY BRIEF HISTORY OF BEER While we have evidence of beer and brewing going back over 10 000 years, the oldest written reference to beer is the “Hymn to Ninkasi” Given birth by the flowing water, tenderly cared for by Ninhursaja! Ninkasi, given birth by the flowing water, tenderly cared for by Ninhursaja! Having founded your town upon wax, she completed its great walls for you. Ninkasi, having founded your town upon wax, she completed its great walls for you. Your father is Enki, the lord Nudimmud, and your mother is Ninti, the queen of the abzu. -

Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions

MISCELLANEOUS BABYLONIAN INSCRIPTIONS BY GEORGE A. BARTON PROFESSOR IN BRYN MAWR COLLEGE ttCI.f~ -VIb NEW HAVEN YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON HUMPHREY MILFORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS MDCCCCXVIII COPYRIGHT 1918 BY YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS First published, August, 191 8. TO HAROLD PEIRCE GENEROUS AND EFFICIENT HELPER IN GOOD WORKS PART I SUMERIAN RELIGIOUS TEXTS INTRODUCTORY NOTE The texts in this volume have been copied from tablets in the University Museum, Philadelphia, and edited in moments snatched from many other exacting duties. They present considerable variety. No. i is an incantation copied from a foundation cylinder of the time of the dynasty of Agade. It is the oldest known religious text from Babylonia, and perhaps the oldest in the world. No. 8 contains a new account of the creation of man and the development of agriculture and city life. No. 9 is an oracle of Ishbiurra, founder of the dynasty of Nisin, and throws an interesting light upon his career. It need hardly be added that the first interpretation of any unilingual Sumerian text is necessarily, in the present state of our knowledge, largely tentative. Every one familiar with the language knows that every text presents many possi- bilities of translation and interpretation. The first interpreter cannot hope to have thought of all of these, or to have decided every delicate point in a way that will commend itself to all his colleagues. The writer is indebted to Professor Albert T. Clay, to Professor Morris Jastrow, Jr., and to Dr. Stephen Langdon for many helpful criticisms and suggestions. Their wide knowl- edge of the religious texts of Babylonia, generously placed at the writer's service, has been most helpful. -

The Role and Function of Beer in Sumerian Society

Armstrong Undergraduate Journal of History Volume 9 Issue 2 Article 1 11-2019 The Beverage of the Ages: The Role and Function of Beer in Sumerian Society Jared Kelly University of California, Berkeley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/aujh Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Kelly, Jared (2019) "The Beverage of the Ages: The Role and Function of Beer in Sumerian Society," Armstrong Undergraduate Journal of History: Vol. 9 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. DOI: 10.20429/aujh.2019.090201 Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/aujh/vol9/iss2/1 This article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Armstrong Undergraduate Journal of History by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kelly: The Beverage of the Ages: The Role and Function of Beer in Sumerian Society The Beverage of the Ages: The Role and Function of Beer in Sumerian Society Jared Kelly The University of California at Berkeley “He who does not know beer, does not know what is good” Sumerian Proverb1 Beer is an alcoholic beverage typically brewed from cereals such as wheat and barley. As a global phenomenon, beer is the world’s most widely consumed alcoholic beverage and the third most widely consumed beverage behind water and tea.2 Beer experienced a convergent evolution developing in many geographically diverse areas such the Far East, the Americas, and the Middle East. In China, a beer brewed from rice, grapes, honey, and hawthorn fruits known as “kui” emerged around 7,000 BCE.3 The Inca Peoples of the Americas brewed a similar drink from maize known as “Chicha de jora,” traces of which have been found at sites such as Machu 1 Stephen Bertman, Handbook to life in ancient Mesopotamia. -

Sumerian Lexicon, Version 3.0 1 A

Sumerian Lexicon Version 3.0 by John A. Halloran The following lexicon contains 1,255 Sumerian logogram words and 2,511 Sumerian compound words. A logogram is a reading of a cuneiform sign which represents a word in the spoken language. Sumerian scribes invented the practice of writing in cuneiform on clay tablets sometime around 3400 B.C. in the Uruk/Warka region of southern Iraq. The language that they spoke, Sumerian, is known to us through a large body of texts and through bilingual cuneiform dictionaries of Sumerian and Akkadian, the language of their Semitic successors, to which Sumerian is not related. These bilingual dictionaries date from the Old Babylonian period (1800-1600 B.C.), by which time Sumerian had ceased to be spoken, except by the scribes. The earliest and most important words in Sumerian had their own cuneiform signs, whose origins were pictographic, making an initial repertoire of about a thousand signs or logograms. Beyond these words, two-thirds of this lexicon now consists of words that are transparent compounds of separate logogram words. I have greatly expanded the section containing compounds in this version, but I know that many more compound words could be added. Many cuneiform signs can be pronounced in more than one way and often two or more signs share the same pronunciation, in which case it is necessary to indicate in the transliteration which cuneiform sign is meant; Assyriologists have developed a system whereby the second homophone is marked by an acute accent (´), the third homophone by a grave accent (`), and the remainder by subscript numerals. -

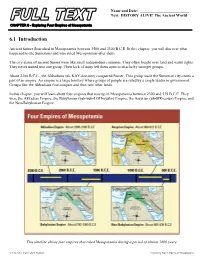

Text: HISTORY ALIVE! the Ancient World

Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.1 Introduction Ancient Sumer flourished in Mesopotamia between 3500 and 2300 B.C.E. In this chapter, you will discover what happened to the Sumerians and who ruled Mesopotamia after them. The city-states of ancient Sumer were like small independent countries. They often fought over land and water rights. They never united into one group. Their lack of unity left them open to attacks by stronger groups. About 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians (uh-KAY-dee-unz) conquered Sumer. This group made the Sumerian city-states a part of an empire. An empire is a large territory where groups of people are ruled by a single leader or government. Groups like the Akkadians first conquer and then rule other lands. In this chapter, you will learn about four empires that rose up in Mesopotamia between 2300 and 539 B.C.E. They were the Akkadian Empire, the Babylonian (bah-buh-LOH-nyuhn) Empire, the Assyrian (uh-SIR-ee-un) Empire, and the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This timeline shows four empires that ruled Mesopotamia during a period of almost 1800 years. © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute Exploring Four Empires of Mesopotamia Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.2 The Akkadian Empire For 1,200 years, Sumer was a land of independent city-states. Then, around 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians conquered the land. The Akkadians came from northern Mesopotamia. They were led by a great king named Sargon. Sargon became the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire. -

The Ancient Near East Today

Five Articles about Drugs, Medicine, & Alcohol from The Ancient Near East Today A PUBLICATION OF FRIENDS OF ASOR TABLE OF CONTENTS “An Affair of Herbal Medicine? The ‘Special’ Kitchen in the Royal Palace of 1 Ebla” By Agnese Vacca, Luca Peyronel, and Claudia Wachter-Sarkady “Potent Potables of the Past: Beer and Brewing in Mesopotamia” By Tate 2 Paulette and Michael Fisher “Joy Plants and the Earliest Toasts in the Ancient Near East” By Elisa Guerra 3 Doce “Psychedelics and the Ancient Near East” By Diana L. Stein 4 “A Toast to Our Fermented Past: Case Studies in the Experimental 5 Archaeology of Alcoholic Beverages” By Kevin M. Cullen Chapter One An Affair of Herbal Medicine? The ‘Special’ Kitchen in the Royal Palace of Ebla An Affair of Herbal Medicine? The ‘Special’ Kitchen in the Royal Palace of Ebla By Agnese Vacca, Luca Peyronel, and Claudia Wachter-Sarkady In antiquity, like today, humans needed a wide range of medicines, but until recently there has been little direct archaeological evidence for producing medicines. That evidence, however, also suggests that Near Eastern palaces may have been in the pharmaceutical business. Most of the medical treatments documented in Ancient Near Eastern cuneiform texts dating to the 3rd-1st millennium BCE consisted of herbal remedies, but correlating ancient names with plant species remains very difficult. Medical texts describe ingredients and recipes to treat specific symptoms and to produce desired effects, such as emetics, purgatives, and expectorants. Plants were cooked, dried or crushed and mixed with carriers such as water, wine, beer, honey or milk —also to make them tastier. -

Women in the Ancient Near East: a Sourcebook

WOMEN IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST Women in the Ancient Near East provides a collection of primary sources that further our understanding of women from Mesopotamian and Near Eastern civiliza- tions, from the earliest historical and literary texts in the third millennium BC to the end of Mesopotamian political autonomy in the sixth century BC. This book is a valuable resource for historians of the Near East and for those studying women in the ancient world. It moves beyond simply identifying women in the Near East to attempting to place them in historical and literary context, follow- ing the latest research. A number of literary genres are represented, including myths and epics, proverbs, medical texts, law collections, letters and treaties, as well as building, dedicatory, and funerary inscriptions. Mark W. Chavalas is Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, where he has taught since 1989. Among his publications are the edited Emar: The History, Religion, and Culture of a Syrian Town in the Late Bronze Age (1996), Mesopotamia and the Bible (2002), and The Ancient Near East: Historical Sources in Translation (2006), and he has had research fellowships at Yale, Harvard, Cornell, Cal-Berkeley, and a number of other universities. He has nine seasons of exca- vation at various Bronze Age sites in Syria, including Tell Ashara/Terqa and Tell Mozan/Urkesh. ROUTLEDGE SOURCEBOOKS FOR THE ANCIENT WORLD HISTORIANS OF ANCIENT ROME, THIRD EDITION Ronald Mellor TRIALS FROM CLASSICAL ATHENS, SECOND EDITION Christopher Carey ANCIENT GREECE, THIRD EDITION Matthew Dillon and Lynda Garland READINGS IN LATE ANTIQUITY, SECOND EDITION Michael Maas GREEK AND ROMAN EDUCATION Mark Joyal, J.C. -

Unit 6: Ancient Sumer Ancient Civilizations Options 5000BCE – 1940BCE

Unit 6: Ancient Sumer Ancient Civilizations Options 5000BCE – 1940BCE Period Overview The Ancient Sumer civilization grew up around the Euphretes and Tigris rivers in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), because of its natural fertility. It is often called the ‘cradle of civilization’. By 3000BCE the area was inhabited by 12 main city states, with most developing a monarchical system. The fertility of the soil in the area allowed the societies to devote their attention to other things, and so the Sumer is renowned for its innovation. The clock system we use today of 60-minute hours was devised by Ancient Sumerians, as was writing and the recording of a number system. The civilization began to decline after the invasion of the city states by Sargon I in around 2330BCE, bringing them into the Akkadian Empire. A later Sumerian revival occurred in the area. Life in Ancient Sumer Changing Times Although starting out as small villages and groups of During the 5th Millennium BCE, Sumerians began to hunter-gatherers, Sumer is notable because of its develop large towns which became city-states. This development into a chain of cities. Within the cities the was made by possible by their systems of cultivation of advantages of communal living soon allowed crops, including some of the world’s earliest irrigation individuals to take on other roles than farming, and a systems. These developing communities then were society of classes developed. At the top of the class able to devote time to pursuits other than gathering system were the king and his family, and the priests.