47-48.Pdf (301.0Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warrane Journal 2008

Autumn 2008. Volume 36, No. 1. ISSN 0310-8104 WARRANE JOURNAL David Gonski ‘Risky’ musical Daniel Manu Mike Munro: In this on ethics in was a triumph presents ‘Life is what Australian for Warrane sports awards you make it’. issue: business drama group College to recognise 35 high achievers with scholar’s medals arrane residents had a very successful academic Engineering 4, Ann Lee, Mechanical and Manufacturing year in 2007, with 35 achieving the distinc- Engineering 4, David Maunder, Electrical Engineering/ tion average necessary to be awarded a College Science 4, Adam McCosker, Medical Science 1, Lincoln WScholar’s medalion. Their efforts will be recog- Morris, Mining Engineering 2, Oliver Nawrot, Chemical nised when the Deputy Vice Chancellor of Sydney University, Engineering 2, John O’Callaghan, Planning 2, Camillus Professor John Hearn, awards the medallions at a special O’Kane, Planning 3, Miguel Paredes, Architecture 2, Alex- dinner on Wednesday May 7, 2008, ander Perrottet, Secondary Teacher Education, Sebas- The scholars for 2007, some of whom are pictured above, tian Sanhueza, Philosophy 4, Kamal Sattar, Commerce are: Dean Berwick Computer Science 1, Thomas Bolton, 3, Vineet Shrivasatava, Mechanical & Manufacturing Optometry 3, Thomas Burger, Petroleum Engineering 3, Engineering 4, Andrew Subramaniam, Engineering/ Com- Christopher Chiofalo, Arts 3, David Claridge, Computer merce 2, Ryan Tebb, International Studies/Law 1, Benja- Science 1, Steven Dejong, International Studies/Law 5, min Ting, Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering -

London 2020 Rights Guide Fiction & Non-Fiction Contents

LONDON 2020 RIGHTS GUIDE FICTION & NON-FICTION CONTENTS FICTION General Fiction Literary Fiction Harlequin Fiction Crime & Thriller Sci-Fi & Fantasy NON-FICTION General Non-fiction Cookery & Lifestyle True Crime Biography & Autobiography Sport History & Popular Science Health & Wellbeing SUB-AGENTS GENERAL ENQUIRIES If you are interested in any of the titles in this Rights Guide or would like further information, please contact us: Elizabeth O’Donnell International Rights Manager HarperCollins Publishers (ANZ) t: +61 2 9952 5475 e: [email protected] HarperCollins Publishers Australia Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street, Sydney NSW 2000 PO Box A565, Sydney South NSW 1235 AUSTRALIA FICTION TITLES GENERAL FICTION GENERAL FICTION It’s New Year’s Eve. Three thirty-something women – Aimee, JOY. MAGIC. WONDER. FATE. Every lost soul can be NOT BAD Melinda and Lou - best friends for decades, let off illegal BOY found again. Fates can be changed. Bad can become good. PEOPLE Chinese lanterns filled with resolutions: for meaning, for SWALLOWS True love conquers all. There is a fine line between magic and freedom, for money. As the glowing paper bags float away, madness and all should be encouraged in moderation. Home BRANDY there’s a bright flare in the distance. It could be a sign of luck UNIVERSE is always the first and final poem. SCOTT – or the start of a complete nightmare that will upend their TRENT Brisbane, 1983: A lost father, a mute brother, a mum in jail, friendships, families and careers. Three friends, thirty years DALTON a heroin dealer for a stepfather and a notorious crim for a of shared secrets, one The day after their ceremony, the newspapers report a small babysitter. -

Older Ignatians' Club

Older Ignatians’ Club Saint Ignatius' College Tambourine Bay Road Riverview NSW 2066 Telephone: 02 9882 8595 The Old Ignatians’ Union invites you and your spouse/partner/carer to attend the Old Ignatians’ Club luncheon at Saint Ignatius’ College Riverview, Cova Cottage on Friday 5 April 2019 at 11:30am Cost: $70 per person Dress: Smart Casual RSVP: by Wednesday 27 March Guest Speaker: Mike Munro (Riverview Past Parent) Mike is looking forward to speaking to Older Ignatians and recounting his motivational story about growing up in a monastery as the only child of a single mother. After growing up in a monastery Mike Munro started his career as a 17-year old copy boy and spent twelve years in newspapers before starting his career in television. In the interim, he spent two years as a newspaper foreign correspondent in New York writing for Australian and British newspapers about America. After joining Channel Ten News, he went on to work for Mike Willesee before becoming a reporter on 60 Minutes. He then went on to host programs like A Current Affair and This is Your Life on the Nine Network and Sunday Night on the Seven Network. In 2014 Mike was made a member of the Order of Australia in the Queen's birthday honours list. His name is now synonymous with the very highest calibre of TV journalism, and recently worked in partnership with Foxtel to produce and host hosted four one-hour documentaries for the History Channel called Lawless — The Real Bushrangers to much acclaim and success. ________________________________________________________________________________ OIC Cova Cottage Lunch Book online using a credit card at https://www.trybooking.com/475142 or if you wish to pay by cheque, please make cheques payable to Saint Ignatius’ College and complete details below. -

News Media Chronicle, July 1998 to June 1999 Rod Kirkpatrick

News MediaAustralian Chronicle Studies in Journalism 8: 1999, pp.197-238 197 News media chronicle, July 1998 to June 1999 Rod Kirkpatrick he developing technologies of pay television and the Internet Tplus planning for digital television provided the backdrop for the national debate on cross-media ownership rules to be revisited. The debate was continuing at the end of the 12 months under review, for the Productivity Commission was inquiring into media ownership rules, content regulations, licence fees and the impending switch from analogue to digital technologies. Some media proprietors were suggesting the new technologies were making the old laws obsolete. At John Fairfax Holdings, another year, another chief executive. Bob Muscat became the third Fairfax CEO in three years to resign. Editor John Lyons departed sacked or otherwise, depending on your source. And there was an exodus of other key Fairfax editorial personnel to The Bulletin in the wake of Max Walshs departure to become editor-in-chief. The major shareholder, Brierley Investments Ltd, sold its 24.4 percent stake in Fairfax, leaving the ownership of Fairfax almost as indistinct as the Herald and Weekly Times Ltd was before News Ltd took over the group. The Australian Broadcasting Authority found that the interests held by Brian Powers (chairman) and Kerry Packer did not breach cross-media ownership rules. It could be loosely said that during the year Rupert Murdoch buried his first wife, divorced his second and married his third. This raised complicated questions of dynastic succession that had previously seemed to be fairly straightforward. Lachlan Murdoch also married. -

Australian Commercial Television, Identity and the Imagined Community

Australian Commercial Television, Identity and the Imagined Community Greg Levine Bachelor of Media (Honours), Macquarie University, 2000 This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Media, Division o f Society, Culture, Media and Philosophy Macquarie University, Sydney February 2007 1 MAC O.UAICI I HIGHER DEGREE THESIS AUTH O R’S CONSENT DOCTORAL This is to certify that I, Cx.............. ¥f/.C>L^r.............................. being a candidate for the degree of Doctor of ... V ................................................... am aware of the policy of the University relating to the retention and use of higher degree theses as contained in the University’s Doctoral Degree Rules generally, and in particular rule 7(10). In the light of this policy and the policy of the above Rules, I agree to allow a copy of my thesis to be deposited in the University Library for consultation, loan and photocopying forthwith. ...... Signature of Candidate Signature of Witness Date this................... 9*3.......................................day o f ...... ..................................................................2qO _S£ MACQUARIE A tl* UNIVERSITY W /// The Academic Senate on 17 February 2009 resolved that Gregory Thomas Levine had satisfied the requirements for admission to the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. This thesis represents a major part of the prescribed program of study. L_ Contents Synopsis 3 Declaration 4 Acknowledgements 5 Introduction 6 1. Methodology 17 2. New Media or Self-Reflexive Identities 22 3. The Imagined Community: a Theoretical Study 37 4. Meta-Aussie: Theories of Narrative and Australian National Identity 66 5. The Space of Place: Theories of “Local” Community and Sydney 100 6. Whenever it Snows: Australia and the Asian Region 114 7. -

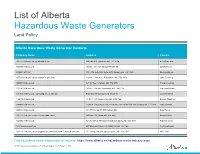

List of Hazardous Waste Generators

List of Alberta Hazardous Waste Generators Land Policy Alberta Hazardous Waste Generator Contacts Company Name Address Contact 1037128 Alberta Ltd o/a Alberta Hotel PO Box 430 Vegreville AB T9C 1R4 Kun Whan Kim 1038900 Alberta Ltd 10945 - 101 AVE Grande Prairie AB Ed McKenzie 1049601 BC Ltd 350 - 7th AVE SW, Suite 2800 Calgary AB T2P 3N9 Michael Baleja 1057974 Alberta Ltd o/a Global Dewatering 16813 - 128A Ave Edmonton AB T5V 1K9 John Devaney 1065579 Alberta Ltd. 42148 Hwy 1 Calgary AB T3Z 2P2 Fiona Kreschuk 1111041 Alberta Ltd. 14325 - 114 AVE Edmonton AB T5M 2Y8 Carmello Mirante 1131895 Alberta Ltd - operating as J.C. Metals P.O. Box 58 Dunmore AB T0J 1A0 Jennifer Millen 1142386 Alberta Ltd. 11404 143 ST Edmonton AB T5M 1V6 Bernie Westover 1148447 Alberta Ltd. c/o MDC Property Services Ltd 200, 1029 17th AVE SW Calgary AB T2T 0A9 Gary Dundas 1204612 Alberta Ltd. #3 - 5504 - 1A ST SW Calgary AB Kulu Punia 1207201 Alberta Limited (Crossroads Esso) PO Box 509 Viking AB T0B 4N0 Kimook Shin 1228002 Alberta Ltd. 72130 R.P.O. Glenmore Landing Calgary AB T2V 5H9 Robert Hoang 1-2-3 Development Inc. 207 Atkinson Lane Fort McMurray AB T9J 1E8 Scott Tenhuser 1237776 Alberta Ltd o/a Dragons Breath Production Testing & Hot Shot 51112 Rge Rd 270 Spruce Grove AB T7Y 1G7 Mike Hall Find hazardous waste information for industry: https://www.alberta.ca/hazardous-waste-industry.aspx ©2018 Government of Alberta | Published: August 2018 | Page 1 of 178 Alberta Hazardous Waste Generator Contacts Company Name Address Contact 1240796 Alberta Ltd. -

Representations of Men and Male Identities

Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) REPRESENTATIONS OF MEN AND MALE IDENTITIES IN AUSTRALIAN MASS MEDIA J. R. Macnamara 2004 REPRESENTATIONS OF MEN AND MALE IDENTITIES IN AUSTRALIAN MASS MEDIA by James Raymond Macnamara B.A. (Deakin) M.A. (Deakin) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, College of Arts, Education and Social Sciences, University of Western Sydney 2004 © J. R. Macnamara, 2002-2004 _________________________________________________________________________ i The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. Signature : Date: 10 December 2004 _________________________________________________________________________ ii © Copyright 2002-2004 This document is copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and Amendments, this document or parts thereof cannot be reproduced in any form without written permission of the copyright owner. Where extracts of this thesis are quoted or paraphrased for research or academic purposes, the source must be acknowledged. _________________________________________________________________________ iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis was guided and assisted by my supervisor, Dr Peter West. His exploration of the position of men and boys in contemporary Australian society inspired me to begin this research and his encouragement and support were generously given throughout. Also this research was supported by associate supervisor, Associate Professor Bob Perry, whose guidance and feedback were invaluable. I am indebted as always to my partner and wife, Gail joy Kenning, who was completing a PhD in digital art during the same period as this research and whose advanced computer knowledge assisted in the setting up of databases and statistical analysis software, as well as being my muse and a pillar of support intellectually and emotionally. -

Charlton Senior Center Trips

Mailed free to requesting homes in Charlton, Charlton City and Charlton Depot Vol. 3, No. 14 COMPLIMENTARY HOME DELIVERY ONLINE: WWW.CHARLTONVILLAGER.COM “A permanent state of transition is man’s most noble condition.” Friday, Apr 3, 2009 Union lawyer: Craver ‘bullying’ union ‘BREAK DOWN’ IN COLLECTIVE BARGAINING PROCESS BY RYAN GRANNAN-DOLL In the meantime, it appears To further cloud the issue, story,” she said. “Why should STAFF WRITER the layoffs will go forward, as Selectman Kathleen Walker, I have to chase after this infor- CHARLTON — Two days Police Chief James A. who is not a member of the mation? Nobody gave me the after selectmen voted to layoff Pervier said he “anticipates” selectmen’s bargaining com- story.” three police officers, the the notices will still be sent to mittee, said she had received Charlton Police Alliance the officers, but Town new information that would ‘COERCED’ union filed a petition with a Administrator Robin L. have caused her to vote to Besides those issues, the state agency asking them to Craver would not confirm continue the collective bar- union’s attorney, Scott mediate a dispute with the that last week. The layoffs are gaining process with the Dunlap, has alleged Craver town over their contract sta- part of the town’s efforts to police union. was “bullying” the union in tus. form its fiscal 2010 budget. “I didn’t have the whole Robin Craver Turn To UNION, page 11 Kathleen Walker State: sex One last bell offender Tucker retiring as middle school head bylaw too BY RYAN GRANNAN-DOLL STAFF WRITER three-sided sign sits on Kathryn strict Tucker’s desk. -

Today's Television

FRIDAY AUGUST 28 2020 TV 39 Start the day Zits Insanity Streak with a laugh Why do cows wear bells? Because their horns don’t work. WhaT do you call a small mother? A minimum! Snake Tales Swamp Today’s quiz 1. What is the Yiddish word that means both poultry fat and something 280820 overly sentimental? 2. In what year did the Titanic sink? Today’S TeleViSion 3. What city is known as the sugar capital of Australia? nine SeVen abc SbS Ten 6.00 Today. (CC) 6.00 Sunrise. (CC) 9.00 The 6.00 News. (CC) 9.00 ABC News 6.00 WorldWatch. 11.00 Spanish 6.00 Ent. Tonight. (R, CC) 6.30 9.00 Today Extra. (PG, CC) Morning Show. (PG, CC) Mornings. (CC) 10.00 Brush With News. 11.30 Turkish News. 12.00 Farm To Fork. (R, CC) 7.00 Judge 4. What herb is sometimes 11.30 Morning News. (CC) 11.30 Seven Morning Fame. (PG, R, CC) 10.30 Kurt Arabic News F24. (France) 12.30 Judy. (PG, R, CC) 7.30 Bold. (PG, known as wild marjoram? 12.00 Desperate Housewives. News. (CC) Fearnley’s One Plus One. (R, CC) ABC America: World News R, CC) 8.00 Studio 10. (PG, CC) (Mav, R, CC) 12.00 MOVIE: A Teacher’s 11.00 Grand Designs Aust. (PG, Tonight. (CC) (US) 1.00 PBS 12.00 Dr Phil. (PGal, CC) 1.00 1.00 MoVie: When Harry Crime. (Mav, R, CC) R, CC) 12.00 ABC News At Noon. News. (CC) (US) 2.00 The Point. -

60 Minutes Australia Tv Guide

60 minutes australia tv guide Continue 60 MinutesGenreNewsmagazineThe createddon Hewitt (original format)Presented by Liz Hayes (1996-present)Tara Brown (2001-present) Liam Bartlett (2006-2012, 2015-present) Sarah Abo (2019-present) Tom Steinfort (2020-present) Country Of OriginAustralia Original Language (s) seasons40ProductionExecutive Producer (s) Kirsty ThomsonProsactory Location (s)TCN-9 Willoughby, New South WalesUnning time60 minutesReallyorious NetworkNine NetworkPicture format576i (SDTV)1080i (HDTV)Audio formatStereoOriginal release11 February 1979 (1979-02-11) - presentChronRelatedology shows60 Minutes (1968-present) External LinksWebite 60 Minutes US Australian version. The tv magazine show 60 Minutes airing from 1979 on Sunday night on The Nine Network. The New york version uses segments of the show. The show is produced under license from its owner Network Ten (from 2017, an Australian subsidiary of CBS News, which owns the format, which premiered in 1968), which also provides separate international segments for the show. Staff In this section are not given any sources. Please help improve this section by adding links to reliable sources. Non-sources of materials can be challenged and removed. (January 2020) (Learn how and when to delete this template message) Current Correspondents Liz Hayes (1996-present) Tara Brown (2001-present) Liam Bartlett (2006-2012, 2015-present) Sarah Abo (2019-present) Tom Steinfort (2018, 2020-present) Former correspondents George Negus (1979-1986) Ray Martin (1979-1984) Ian Leslie (1979- 1989) -

Women, Politics and the Media

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Women, Politics and the Media: The 1999 New Zealand General Election A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Communication & Journalism at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand. Susan Lyndsey Fountaine 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to say thank you very much to my supervisors, Professor Judy McGregor and Dr Margie Comrie, from the Department of Communication & Journalism at Massey University. Their guidance, insight, on-going support and humour sustained me, and were always greatly appreciated. Thank you to all the women politicians who participated in the interviews, especially Marian Hobbs, who gave up valuable time during the election campaign. I also acknowledge the help of Associate Professor Marilyn Waring in gaining access to National women MPs. There are many other people who gave valuable advice and provided support. Thank you to Dr Ted Drawneek, Mark Sullman and Lance Gray fo r much-needed statistical help, and to Shaz Benson and Wendy Pearce fo r assistance with fo rmatting and layout. Thanks also to Doug Ashwell and Marianne Tremaine, "fellow travellers" in the Department of Communication & Journalism, and Arne Evans fo r codingvalidation. I would also like to acknowledge the assistance I received from Massey University, in the fo rm of an Academic Women's Award. This allowed me to take time off from other duties, and I must thank Joanne Cleland fo r the great work she did in my absence. -

DINGO MEDIA? R V Chamberlain As Model for an Australian Media Event

DINGO MEDIA? R v Chamberlain as model for an Australian media event Belinda May Middleweek BA (Hons 1st class) Sydney A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Sydney March 2007 As surely as Azaria was taken by a real dingo, the Chamberlains were taken down by a pack of baying journalistic dingoes and their publishers – the Adelaide News, the Sydney Sun, and the Murdoch press. Michael Chamberlain and Lowell Tarling, Beyond Azaria: Black Light, White Light, (Melbourne: Information Australia, 1999), xiv. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract Acknowledgments List of Abbreviations Chronology Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Metaphorisation 1980-1982 29 Tabloids, Broadsheets and the Azaria Event Breaking the Story: August 17, 1980 The Dingo: An Unlikely Thief? The Mother: Anguished Mum Tells The Victim: The Dingo Baby “Ayers Rock”: The Dead Centre Religion: An Ambassador for Jesus Conclusion Chapter 2: Dissemination 1982-1984 62 Waltzing Azaria The Phantom Public Sphere The Popular, Private Eye and Forensic Campaigns The Counter-Publics Hitchcock and Television Conclusion Chapter 3: Commodification 1984-1986 100 Celebrity as “Commodity” and R v Chamberlain as Precedent Chequebook Journalism and a “Live” Judgment about “Death” Frocks, Politics and Feminist Discourse “Controversial Women”: Chamberlain, Lees and Hanson The “Rescue Plan”: Magazines and the Reclamation Process A “Womb with a View”: The Textual Body Conclusion Chapter 4: Mythologisation 1986-1988 143 Media Discourse: